In some parts of the world, you can get by without a wallet, as cash and credit cards are totally unnecessary. These aren’t remote rural villages either, but rather metropolises such as Shenzhen, China, an urban hub for technological innovation that’s located just north of Hong Kong.

In an episode of The Wall Street Journal’s Moving Upstream, Jason Bellini shows how this Guangdong city operates as an almost-cashless society. Residents pay for everything from food to transport to consumer goods using only their smartphones, either by scanning QR codes or sending money via apps. Alibaba’s new grocery chain, Hemna, for example, looks like any other neighborhood supermarket. Except, shoppers can scan bar codes to look up more information about items, then pay at self-checkout stands by holding up their phone (some stores will even just scan your face). Three-quarters of the city’s fast food purchases are made using mobile devices, and taxi drivers prefer to take payment via WeChat. In 2016, Chinese citizens send a staggering $9 trillion through their mobile devices, and the number is only growing.

We don’t think much of it, but wallet designs in the last five hundred years have tracked the changes in our political economy. And as society becomes ever more reliant on digital technologies, it’s hard not to think that we’re on the cusp of some new designs.

Among Western societies, the first wallets came with the advent of paper currency. In 1690, the Massachusetts Bay Colony was authorized to raise troops to help fight in King William’s War. The King allowed the colony to pay soldiers with Bills of Credit – a promise to pay in the future – printed on paper. Other colonies followed by issuing their own promissory notes in subsequent military conflicts. And as these notes became increasingly common, so did wallets.

Prior to this, men carried things in simple, drawstring leather bags, which they hung from their waist (like a fanny pack of sorts). In fact, while men’s breeches have been made with built-in pockets since the late 1600s, they often remained empty. Elites had hard views about soft bags, and they considered it uncivilized to transport anything outside of a belt-hung pouch. Respectable gentlemen used fanny packs; barbarians and thieves stuffed things into their clothes. In an 1889 essay cataloging the ways humans carry things, anthropologist Otis Mason had this to say about pockets:

This method of conveyance is scarcely worth mentioning from the civilized point of view; yet when we consider the endless variety of small merchandise carried in the pockets of men and women and remember that all these pockets are for no other purpose than to serve as instruments of transportation, we can not omit including it. We must remember also that the Oriental, especially the Corean, has pockets in his sleeves having the capacity of a half bushel. The Turk and the Arab stows away as much as this in the ample folds of his robe, and any boy who has stolen fruit can add his testimony.

Of course, men everywhere carry things in their pockets nowadays, but the changing modes of how they carry those things track the way we’ve organized our economy.

The billfold, for example, is a physical manifestation of how we’ve moved into a credit-based economy. After the Second World War, during the period known as the Golden Age of Capitalism, Americans increasingly relied on consumer credit. In 1950, The Diners Club was the first to consolidate multiple charge cards, making it the first “general use” card that allowed people to pay multiple bills with one statement. After that came Carte Blanche, American Express, and dozens of new consumer credit agencies. As consumers collected more cards, they needed specialized wallets with multiple card slots – thus how we wound up with a billfold on top of every American dresser.

Today we have everything from bi-folds to tri-folds to uncomplicated cardholders. But for men who wear suits and sport coats, the interior breast pocket (what tailors call an in-breast pocket) has remained unchanged. It’s a simple compartment that can hold any kind of wallet – but a coat wallet is best.

Coat wallets, which are sometimes called dress wallets, were literally made for tailored clothing. They’re tall and slim, and thus slip into an in-breast pocket without breaking the jacket’s line. Since everything is vertically orientated, you don’t have to fold it over on itself. That means it’s thinner than a bulkier, brick-like billfold. They’re perfect for softly tailored jackets, as they don’t add any visual bulk. And since they sit closer to the top of the pocket’s opening, they’re easier to grab. Pictured above are some coat wallets from Henry Poole, Ettinger, and Voxsartoria’s personal wardrobe.

In today’s streamlined economy, however, coat wallets can feel antiquated. Original models were made to hold a checkbook, some paper money, and upwards of twenty credit cards. These, after all, are from the era when people carried diner cards, department store cards, traveler checks, train tickets, and all sorts of other items.

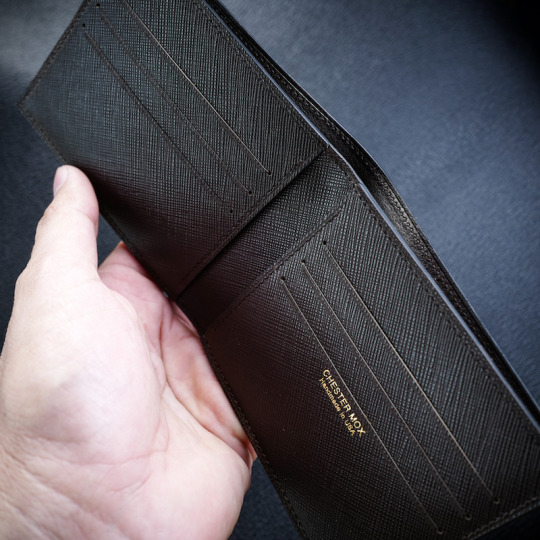

I’ve wanted a coat wallet for a while, but I don’t live like Rich Uncle Pennybags. These days, I carry everything in a Chester Mox card case and an Elsa Peretti money clip – a little cash, in case of an emergency, then three credit cards, a debit card, and a driver’s license. The card case is great, but sometimes it gets lost at the bottom of my pocket, sandwiched between my cell phone and keys. When I go to fetch it, my hand feels like it’s swimming around in a fish bowl trying to find the lucky ticket in a lunch drawing.

So, a couple of weeks ago, I reached out to Chester Mox to commission a custom coat wallet through their bespoke program. The idea was to create the perfect wallet to use with suits and sport coats – something razor thin and somewhat tall, so it has all the advantages of a traditional coat wallet, but also works for someone who isn’t carry around a small national economy.

I’ve been a fan of Chester Mox for years and think they offer some of the best-value leather goods around. Everything is handcut and handsewn to a quality level that competes with the best makers around the world. Machine-made leather goods, which is what you’ll almost always find from designer labels, have straight seams, such that each stitch sits perfectly in-line with the next. Chester Mox, on the other hand, uses what’s known as a handsewn saddle-stitch. That’s when two needles pass through the same hole, either with an awl first piercing that hole and guiding a needle through, or with the holes punched by hand using a pricking iron. The technique is laborious, but it results in a stronger seam. Whereas machine-sewn seams can unravel if one stitch breaks, saddle-sewn ones have to be picked apart using a special tool.

For this wallet, I went with a matte, navy alligator leather sourced from Heng Long, a Singaporean supplier that has soft exotics. Lower-end exotics are typically made from caiman, a nasty and hard leather that’s prone to cracking. Or the maker will cut from the hide’s flanks in order to save on material. Chester Mox cuts from the belly, which other companies typically save for bigger ticket items such as purses. The result is a cleaner looking, softer leather good with well defined scales. The interior for this wallet was then lined with a gray French Chévre leather from Alran.

Bellanie at Chester Mox says cutting alligator leather requires special attention. “You have to carefully measure the scales so the product looks balanced,” she says. “If you’re not careful, the panel may have less shank on one side than the other, or the scales can look crooked. Additionally, we have to look for small imperfections. They can be easy to miss in a large hide, but will be noticeable in the final product.”

Bespoke projects start with the customer providing some ideas or photos, which Chester Mox then translates into a sketch. “I send the preliminary sketch to the customer, so he or she can have an idea of how the finished product will look,” says Bellanie. “Once the customer confirms, I make a final draft using graphing paper, then transfer it to the computer to generate a more precise template. This is then printed out and used to cut the leather pieces required for the project.” The process isn’t too different from how a tailor makes a paper pattern for a garment.

For this wallet, we went with two small pockets on the right side, which are made to hold up to six cards per pocket. There’s a hidden pocket behind those slots to stow receipts and subway tickets. The pouch on the opposite side is then used for cash. I had the pouch cut away a little so that I wouldn’t have to bend the leather back to get money. The little notch you see at the top is to keep the leather from pulling directly on the threads.

By stacking two card slots next to each other, the wallet is thinner than most other designs. Even with ten cards and ten folded bills, as shown below, the wallet is little more than twice the thickness of my sport coat’s lapel edge. It’s also larger than a card case, so it’s never too far from the top of an in-breast pocket. It’s easy to grab and holds everything I need without excessive space leftover. I think it it’s the perfect wallet for use with suits, sport coats, and formal wear.

Since the pattern for this wallet has already been made, Bellanie says it can be ordered again without a bespoke upcharge. The same model in a more basic leather, such as French Chévre, would cost around $370. Optional add-ons, such as a hot stamped monogram, are also available. Exotic leathers will obviously cost more.

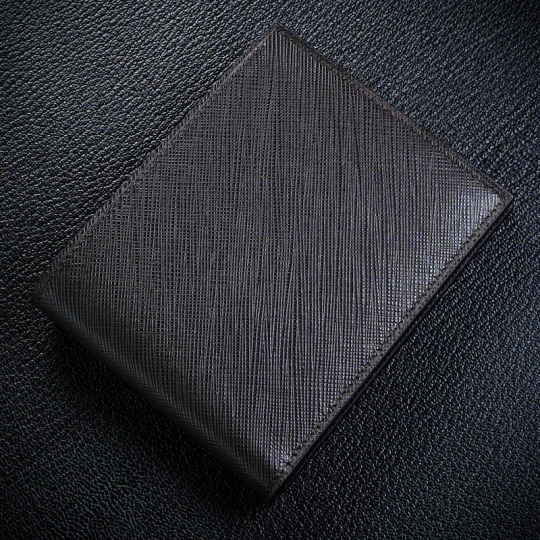

Lastly, Chester Mox is planning to introduce a more affordable line of ready-made, machine-sewn leather goods later this year. They’ll cost 20% less than the company’s handsewn offerings, but will still be made from the same materials. “Our machine stitching is very neat and durable,” says Bellanie. “We’ve narrowed the thread spacing so it looks refined.” Below are some photos of their samples, which include a tan key fob and Saffiano calf billfold. Chester Mox also now stocks Horween’s “Russian” hatch grain leather, which is made to look like the Russian reindeer leather found in a 18h century Baltic ship sunken off the coast of the Plymouth Sound. That leather in a rich saddle brown, coupled with a racing green interior, would look great as a coat wallet – just shorten it a little so it works for a modern economy.