For being an iconic shoe, I’d be surprised if more than a hundred people have worn J.M. Weston’s Chasse. It’s one of the company’s flagship designs, but unlike their versatile 180 loafer, it’s a very particular. Chasse is French for hunt, so J.M. Weston’s Chasse is the company’s hunt derby. It’s a split-toe design with a short snout, bulky Norwegian welt, and triple-leather sole. It has a tank-like silhouette that wears you, rather than you wear it. Supposedly it was made for tromping out somewhere in the French countryside, presumably to hunt for compliments, although I’ve only seen them worn by shoe enthusiasts in Japan.

Still, I’ve always liked the idea of a rustic split-toe, something more in keeping with the style’s workwear roots, rather than the sleek and sophisticated town models you see everywhere today. I’ve been working with Nicholas Templeman for the last year on a new bespoke commission that’s inspired by Chasse, but is toned down enough for San Francisco. The idea is to get a split-toe that sits perfectly between town and country – wearable in everyday environments, but also looks at home with tweed and denim.

That’s meant getting certain details right. My last had to be adjusted to reflect a shorter and more rounded toe shape; a seam has been made going from the quarters to the facings. I’ve also opted for a bellow tongue, which means a bit of kidskin leather has been used to connect the tongue to the facings. This is typically done on country shoes to prevent rain or pig slop from seeping in. Or, in my case, used to justify to myself why I’m getting custom shoes.

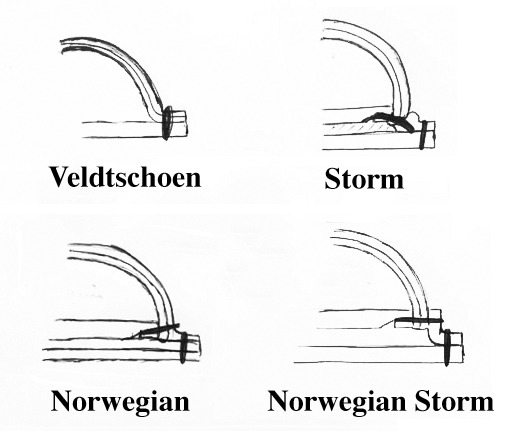

Some of the more interesting bits include how the welt and apron are being made. Weatherproof shoes traditionally rely on a more unique construction in order to stop water from sitting in the seam between the welt and upper, which in extreme instances can cause rot. Generally, this means something like a Veldtschoen construction, storm welt, Norwegian welt, or the very rare Norwegian storm welt. (Nicholas supplied the illustrations you see above).

“A Veldtschoen and Norwegian look similar in the sense that both have turned out uppers,” says Nicholas. “However, you can spot the difference because a Veldtschoen doesn’t have stitching through the welt and upper to secure everything, like you’d find on a Norwegian. A storm welt is a different thing again. Instead of a flat, belt-like welt, it has a ridge or bump running down the length of the shoes, which helps keep out water. The last is a Norwegian storm welt, which is sewn the same way as a Norwegian, but with the strip laid against the upper pointing down. Then you turn the welt into an L shape and stitch as normal.”

Each of these constructions has their pros and cons. The Veldtschoen is the simplest of the four, which means it yields a softer and more flexible shoe. However, it’s also the least water-resistant. A Norwegian storm sits on the other side of the spectrum. It’s chunky and heavy, and requires thick leather uppers to match, which means it takes a while to break in. On the upside, the secure construction will protect you from nearly anything (including people’s admiration).

For my pair, we went with a regular welt. It’s a good construction for light rain and normal city use (I’m unlikely to walk around in heavy rain anyway), and it’ll lend a more manageable silhouette under tailored trousers. At the back, there will be what shoemakers call a welted seat (what some may know as a 360 degree welt). Heels aren’t normally welted, so when you extend the welt like this, you give the shoes a chunkier look without crossing into Norwegian territory.

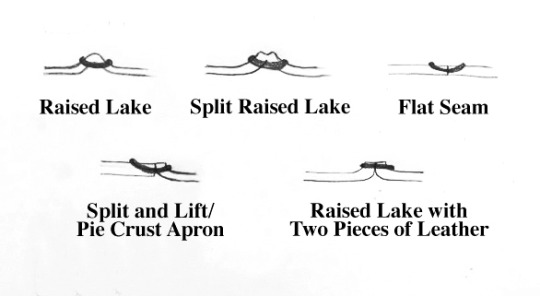

The apron has been the hardest part to get right. The Chasse is made with what’s known as a flat seam, where two pieces of leather are butted up against each other and then connected through a U-shaped stitch. Since the leather sits end-to-end, you don’t get the lip that forms on a raised lake (which was used on my first pair of bespoke shoes). Unfortunately, it’s also difficult to execute.

A flat seam is made by first piercing the leather with an awl, which goes halfway into the skin. A needle and thread are then passed through the holes and the seam is pulled tightly. If the leather isn’t thick or stout enough, however, the seam can break through the leather (or the leather crumples in an unsightly way). That happened on the first two trials of my order. Some Japanese makers solve this by using thicker boot leather, but then we land back at the original problem. A heavier leather means a heavier looking shoe, which may feel out of step with tan whipcords and grey flannel trousers.

Nicholas came up with the ingenious solution of doing a wholecut split-toe, which means the top of the shoe, what’s known as the vamp, is made from one continuous piece of material. This allows him to do a decorative flat seam without pulling the stitching too tight. Being a wholecut derby, the facings have to be made from separate pieces of leather, but the entire design is so busy that I don’t think anyone will notice anyway.

This whole project has made me appreciate the value of working directly with a small, maker-run shop. Unlike with a larger house such as G.J. Cleverley, I’ve been able to work directly with Nicholas on details I think would mark me as a nuisance elsewhere. A friend of mine in Boston has bespoke shoes from every company imaginable – including each of the big West End firms to smaller makers around the world. When I asked him a couple of years ago where I should turn for my first pair of bespoke shoes, he said Nicholas Templeman. “You’ll get more individual attention,” he said. He was right.

For those interested, Nicholas is touring the United States this coming week, starting off with a Boston trunk show on October 31st, then moving on to NYC and San Francisco. You can see his travel schedule on his website. If you’ve been thinking about getting a pair of bespoke shoes, I couldn’t recommend Nicholas more. He’s great at leading customers through each step of their orders, which allows them to specify the smallest of details. His prices are also a bit lower than most. Pictured below are some of the shoes he’s made for clients in the last year, as well as his new dog. Unfortunately, the dog does not yet accompany Nicholas on these US trips.

(photos via Nicholas Templeman’s Instagram and Manolo)