The internet is overflowing with information nowadays about custom tailoring, but I find the best information still comes from traditional networks – privately talking with friends who share an interest in the subject, as well as online acquaintances who’ve had bespoke clothes made. This is especially true if you’re interested in Italian style. In London, most tailors work for one of the large tailoring houses on Savile Row, which means you can easily walk down that street alone and find a reputable maker.

In Italy, things are different. The firms are smaller; the tailoring houses less well-known. People are scattered throughout cities, which means they can be harder to find. In Naples, for example, tailors are often tucked away inside hidden courtyards and even apartment buildings, operating in workshops that have no commercial signage. The city at times reminds me of when I lived in Moscow. There, you often have stores hidden inside large, imposing buildings that otherwise serve as residential complexes. You’d never know they were there unless you were from the area – or talked to a local who could show you around.

Since few Italian tailors visit the United States, I’ve been planning a trip to Italy to visit them. As such, I’ve turned to friends for recommendations on new tailors to try. Kentaro Nakagomi, the founder and designer behind Coherence, recommended I check out Sartoria Marinaro, which is based in Florence. “It has that good old smell,” he said.

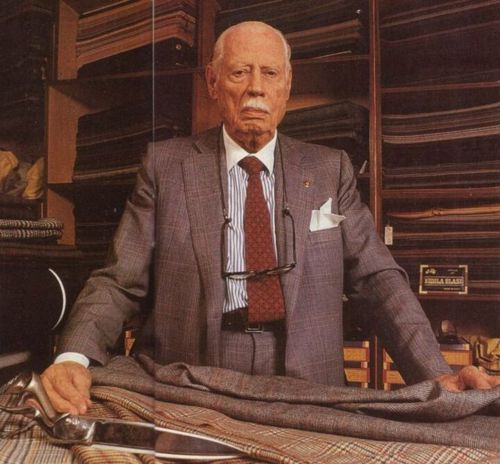

The firm isn’t run by anyone named Marinaro. The head cutter is Mario Sciales, who began his career in his hometown of Naples at the age of ten. He was actually an apprentice of Angelo Blasi, one of Naples’ legendary cutters and the man pictured above. In the early part of the 20th century, Neapolitan tailoring was largely defined by Blasi, who specialized in a more traditional English-inspired cut, and Vincenzo Attolini, who worked as a head cutter for Rubinacci (then known as London House). Attolini revolutionized the region’s style by drawing on Domenico Caraceni’s tailoring books, and Neapolitan tailors have followed his lead ever since. He’s the reason why we associate Neapolitan style with soft, deconstructed jackets.

In the 1960s, well after the fights between Attolini and Blasi, Mario Sciales moved to Florence, where he worked for Michele Marinaro. And when Marinaro passed away, Sciales took over the firm, which he continues to lead today. Along with meeting clients in Florence, he travels to New York City a few times a year. His daughter often accompanies him and serves as his translator. Prices, I hear, are very reasonable.

George Wang of BRIO recently commissioned some things from Sartoria Marinaro: a navy double breasted blazer with silver buttons, as well as a gray, three-button business suit. He tells me one of the things that stand out is the lack of pretension. Many blogs, including this one, are filled with stories about Neapolitan maestros, who will greet you at their ateliers with a cup of espresso and a friendly chat. George tells me the workshop here is nothing like that:

Mario’s shop isn’t anything like modern tailoring houses such as Liverano or Rubinacci, nor is it like the modest ateliers we associate with independents such as Mussella or Corcos. It’s a classic tailoring shop, where you’ll find clothes in various stages of finishing, some tailors, and Mario himself. There aren’t any interesting pieces of art, no amazing vintage fabrics, no cool mid-century furniture, no weekend antique market finds. It has zero charm. Mario is a straightforward man – he’s a tailor you see to get clothes made. He’s not a friend, father figure, passionate artisan, or any of the terms people like to use to describe tailors who overcharge them for clothes. But if you understand what’s on the table, the work is great.

In some ways, the tailoring here is distinctively Florentine – fronts cut without any visible darts, unlike what you’d find further south (where Neapolitans like to cut jackets with extended darts). This can be especially nice on patterned fabrics, as you get a cleaner execution on the resulting jacket. Without the dart, the pattern stays clean and uninterrupted. Similarly, the lapels are cut very straight, sometimes in a way that even looks concave when worn. In this way, the jacket exemplifies those sort of sweeping lines we’ve come to associate with Florentine tailoring. You can see this more clearly in the gray single breasted suit below.

The difference is that the suits feel a bit more conservative than what you might get from Sciales’ neighbors. The shoulders are a bit more structured, often in ways that we’d associate with 1940s and ‘50s tailoring. The quarters, while gently open, aren’t as exaggerated as what you’d get from Liverano. And the jackets are a bit longer, which give them a lengthening silhouette. George characterizes his jackets as being “not as full bodied and rounded as Liverano, but also not as slim and slouchy as Seminara.”

It takes a lot of work to build an international clientele, and many houses are now hip on how to use social media to reach a wider audience. I’m hoping to get to Italy sometime later this year, or possibly early next, where I’ll try out some lesser known houses. Not that either kind of business is better or worse, but the second seems more interesting. Marinaro is certainly on the list.