This post is sure to please no one. Not traditionalists who have no interest in anything outside of a coat and tie. Not workwear purists who dislike any kind of pre-distressing. And certainly not anyone who knows the name of this blog, who will rightly wonder why they’re reading about workwear on a site called Die, Workwear! But, so it goes …

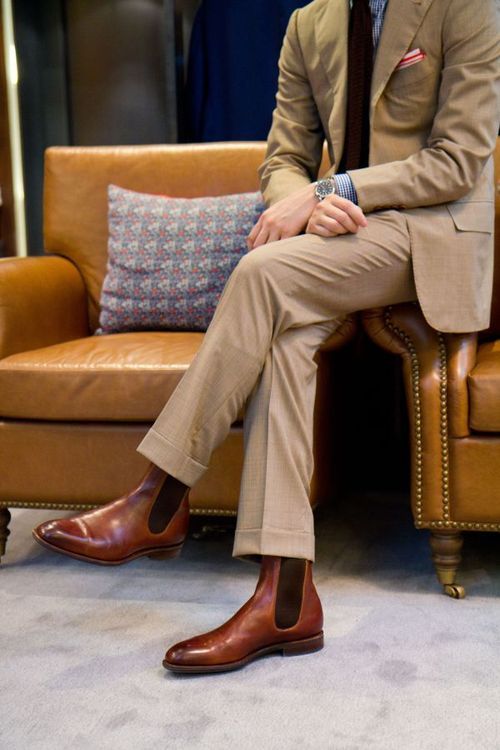

Lately, I’ve been really impressed with Chimala. It’s a Japanese line that started in 2006, originally with a focus on women’s collections, but has recently expanded into menswear. Pants tend to fit a bit loose and full, and have a casual, carefree sensibility that I think is refreshing today’s skin tight fits. Coats and shirts are a bit slimmer, with the second being more so than the first. The line is slightly reminiscent of Japanese brands such as 45rpm, and will probably appeal to the same fan base.

Unfortunately, the nicest aspects of Chimala’s line – the subtle detailing and fabrication – don’t come through well in photos. Like the new Barbour Beacon collection, which is now designed by Norton & Sons’ Patrick Grant, these are clothes you have to handle in person to appreciate. This last season, for example, they made a navy shirt jacket from a really interesting wool/ nylon material. The fabric had a nice spongy feel to it, and seemed well suited for transitional weather. There were two side-entry pockets at the front with reinforced stitching, elbow patches at the sleeves for detailing, six corozo buttons for front closure, and a drawstring hem which, from what I could tell, was mostly for decoration. I really wanted to purchase it for wear with casual chinos, but figured nobody would pay the full retail price of $400. “I’ll smartly wait until it goes on sale, and get it at 40% off,” I thought. A week or two after first seeing it, my size sold out, and most of the remaining sizes went quickly after that.

There was also a really nice chambray shirt with many “standard” vintage details - vintage style buttons, triple needle construction, and run off chain stitching at the hem. Two pockets decorated the chest, with non-wonky cuts for people who are a bit tired of the strange designs that adorn shirts these days. The only controversial thing is the finishing. The shirt had been heavily washed and pre-distressed, and there was “faux darning” at the collar and one of the cuffs, which you can sort of make out in this photo. Light brown staining had also been applied to one of the chest pockets. You can see similar details in their women’s line, such as this chambray shirt reviewed by Archival Clothing.

Keep reading