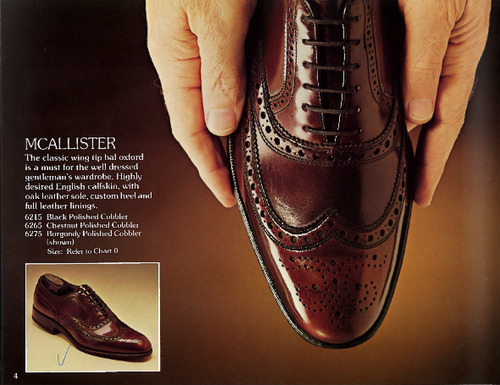

Most of the shoes we buy as style enthusiasts come from England, Italy, and the United States, but other countries have rich shoemaking traditions as well. Japan, for example, has a vibrant community of bespoke cordwainers, who are renowned for their sleek styling and shapely lasts. Certain countries in Central Europe also uphold a long Austro-Hungarian tradition, which includes making a unique style known as the Budapester – a brogued derby with high walls, large medallions, and slightly upturned toes.

In the past few weeks, as fall has been approaching, I’ve been eyeing a few of those Central European makers. They’re not always pretty to look at online, but once you imagine them underneath cavalry twills or corduroys, and paired with a thick and heavy tweed jacket, they suddenly make more sense. They’re country shoes, standing opposite to the slick city oxfords that men wear with business suits, and are great with casualwear (tailored or otherwise).

One such maker is Ludwig Reiter – an old, old Viennese firm that has been around for almost 130 years. As the story goes, the company started as a small workshop, but then grew to supply custom-made boots to the Austro-Hungarian Army. Sometime in the early 20th century, the owner’s son, Ludwig Reiter II, spent time traveling between Germany, England, and the United States, working at various footwear factories along the way. When he returned to Vienna, he came with the knowledge of how to make Goodyear welted shoes, so with some retooling, he turned his father’s boutique into a factory. Four generations later, Ludwig Reiter now makes some of the best Goodyear welted shoes in a slightly more “modern” take on classic Austro-Hungarian style.

Keep reading