Shots were fired in the late summer of 1777, a year after the United States declared independence, as some 15,000 British soldiers descended onto Philadelphia, then the seat of the rebellious Second Continental Congress. After some hard-fought battles that resulted in over a thousand Continental Army deaths, the British marched into Philadelphia unopposed. The Continental Congress first relocated to Lancaster and then York, leaving civilians behind in Philly. One of those civilians was Molly Rinker.

Molly Rinker, also known to friends as Old Mom Rinker, was a matronly woman who ran a Philadelphia tavern. While George Washington and his troops were encamped just a few miles outside of the city, Mom Rinker closely tended to British soldiers and Tories, keeping their plates full, their beer pitchers flowing, and the conversation animated. But her intentions went beyond just providing good service. While drunken redcoats chatted away, Mom Rinker picked up bits and pieces of information, which she then covertly jotted down in the backroom. Each night, she wrapped her notes around tiny stones, and then hid those stones inside large balls of yarn. And on the following day, she took her knitting needles and yarn to the outskirts of town, where she’d climb high atop of a rocky ridge. From this vantage, Mom Rinker could easily survey the area. She would then sit down and proceed to innocently knit.

With yarn strewn around her and knitting needles in her hand, Mom Rinker was a portrait of tranquil domesticity. British soldiers who may have seen her from afar suspected nothing. But from this position, Mom Rinker could see when a Continental soldier emerged from the brush below. When she did, she’d gently nudge a ball of yarn over the brink, causing it to tumble to the ground, and the soldier would then scoop up, pocket, and carry her priceless message to George Washington. Old Mom Rinker, who never dropped a stitch, was America’s first and perhaps only sweater-making spy. She turned cloak-and-dagger techniques into yarn and knitting needles.

When we think about American style, we mostly think about items that landed here from abroad, such as Indian madras and Norwegian loafers. In our closets and dresser drawers, many of us have neatly stacked piles of Fair Isles, Shetlands, Norwegians, and Irish Arans, all knitwear styles named after the regions in which they were born. We learn about their histories through marketing pamphlets and vanity books designed to sell us more clothes. It’s said that in the thinly populated Shetland Isles, the yarns used to make sweaters were originally spun in the home, where they were apt to soak up domestic odors. If Brooks Brothers’ lore is to be believed, those standing near one of the company’s first Shetland knits could faintly detect the smell of smoked herring or boiled cabbage on damp days.

Until recently, little has been written about sweaters made in the United States, possibly because hand knitting has been traditionally associated with poverty, mundane domesticity, and feminine kitsch. In his 1987 book A History of Handknitting, Richard Rutt puts it plainly: “Information about the history of hand knitting in the United States is hard to find.” Yet, knitting in America is about more than personal industry or duty to the home. Its history is interlaced with deliciously rich stories full of social meaning, spiritual satisfaction, and at times, even political subversion.

Along with the muskets and cannons that were fired during the Revolution, this country’s independence was fought with knitting needles, not just those in the hands of Old Mom Rinker, but thousands of other women. In the years leading up to the Revolution, colonists made and wore their own clothing, first as part of their domestic production, then as a symbol of resistance, and finally as an open revolt against Britain. As a response to the crown’s increased taxation on everyday items, the colonies began boycotting British goods, including luxury silks, worsteds, and woolens, as well as essential items such as knitted stockings. Shortly after the Stamp Act of 1765, the Virginia Merchants Association laid out a long list of British products that could no longer land on colonial shores: “Lawn, Muslin, Gauze, except Boulting Cloths, Callico or Cotton Stuffs of more than Two Shillings per Yard, Linens of more than Two Shillings per Yard, Woollens, Worsted Stuffs of all Sorts of more than One Shilling and Six Pence per Yard.” An exemption was made for “Plaid and Irish hose,” I assume because someone treasured their argyle socks.

In response, colonial women transformed their social “spinning bees” into revolutionary “spinning meetings.” Men looked on as women competed to spin, sew, and knit all types of fiber goods to make up for the loss in boycotted materials. During the lowest points of the Revolution, industrious women also patched up, darned, and unraveled threadbare clothing to make “new” shirts, stockings, and blankets for shivering soldiers fighting on the frontlines. “[W]omen’s knitting allowed the colonies to gain critical independence from the tyranny of imported British goods even before they gained political independence as a country,” Tove Hermanson writes in “Knitting as Dissent: Female Resistance in America Since the Revolution.” “The success of America’s boycott of British textiles and goods was dependent upon women’s endorsement and active contributions, no small feat as it significantly increased women’s workload.”

Although knitting in America remained mostly invisible, partly because domestic work often goes unrecognized, the activity continued to play an important role in American life. During the 19th century, abolitionist women shared political ideas in sewing circles. During both World Wars, American knitters made socks, shawls, and sweaters for soldiers and refugees abroad. But shortly after the Second World War, knitting went into a lull in the United States. Second-wave feminists saw the activity as a symbol of women’s oppression, a holdover from the Victorian social order that tied women to domestic drudgery. “This refusal to acknowledge the empowering and political aspects of knitting in the ’60s and ’70s echoed the equally puzzling reluctance of colonial women who refused to name their politically motivated knitting groups with explicitly political names,” Hermanson writes. “Perversely, in the name of feminism, many women willfully rejected the importance and value of women’s knitting precisely because it had always been a dominantly female activity.”

However, in the last thirty years, knitting in America has undergone a revival, as “craftivists,” feminists, and anti-capitalists have proudly reclaimed its history. “The Riot Grrrl movement, which emerged out of the punk scene in the United States in the early 1990s and influenced the trajectory of third-wave feminist politics, aesthetics, music, and engagement with popular culture, has also left its mark on contemporary DIY culture, and the effects can be seen in contemporary knitting culture as well,” Beth Ann Pentney writes at the online feminist journal thirdspace. “Personalized and unique hand-knit objects have been used to eschew mass production in favor of non-corporate, small-scale production, often in support of women-owned local suppliers, yarn shops, and designers.” Since the ’90s, knitting has been used to champion various progressive causes, including anti-war efforts and the pro-choice movement. In 2017, the pink knitted “pussy hat” emerged as a symbol of resistance to an administration led by a man who said he was allowed to grab anything.

A few months ago, as I was rummaging through my dresser drawer, I rediscovered an old Eidos sweater I bought back when the label was still being designed by Antonio Ciongoli (now at 18 East). It’s made from a mixture of black and indigo yarns, which are spun from the slightly coarser hairs on a cashmere goat’s undercoat fleece. It’s soft, spongey, and beautifully textured. Known as a Shaker style, this type of sweater is named after a tiny, radical Christian sect that bloomed out of the Northeast. In my mind, the Shaker is America’s most iconic knitwear style, a symbol of this country’s great history and some of its highest ideals.

A wild and wooly bunch, these Christians arrived here from Manchester, England, and first settled in New York around 1774, on the eve of the Revolution. Originally known as the “Shaking Quakers” for their frenetic spiritual expressions during worship services, they were committed to living an authentic life of Christ. They believed in pacifism, communalism, celibacy, and, most of all, equality. Anyone could enter their community so long as they confessed their sins and handed their material wealth over to communal life. In these collectives, members shared tasks and responsibilities, and with that, food, necessities, and the fruits of their labor.

Nearly a hundred years before the emancipation of slaves, and one hundred fifty years before women were allowed to vote in the United States, the Shakers were already practicing a radical version of equality. Men and women shared leadership roles throughout the Church’s structure. Mother Ann Lee, an illiterate British factory worker who was a founder and touchstone figure for Shakerism, preached that celibacy and confession were the only true road to salvation. In the early 19th century, Shakers freed slaves belonging to members and bought the freedom of Black Believers. They welcomed Black Shakers into their communities. In a print of the Mt. Lebanon church, produced sometime around 1830, you can see Black and white Shakers dancing together, dressed in the same clothing and performing the same dance steps. Many Shakers also came out in the 1960s to support the Civil Rights movement.

At its peak in the mid-19th century, there were an estimated 6,000 Believers living in about two dozen monastic communities. Today, there’s only one active community, the Sabbathday Lake Shaker Village in Maine. Its website lists just two members, Elder Arnold Hadd and Eldress June Carpenter. “Shakerism is not, as many would claim, an anachronism; nor can it be dismissed as the final sad flowering of nineteenth-century liberal utopian fervor,” they write on their website. “Shakerism has a message for this present age — a message as valid today as when it was first expressed. It teaches above all else that God is love and that our most solemn duty is to show forth that God, who is love in the world.”

About a year ago, Portland Press Herald editor Peggy Grodinsky joined Brother Arnold for a public talk about Shakerism. She asked him what’s the most challenging part about being a Shaker. The celibacy? The monasticism? The work? “Nay,” Brother Arnold replied. “It’s the community.” When put into diverse groups with people with whom you share no common background, experiences, or even goals, you’re called upon to love these people without boundary because they’re all an expression of God.

“I [once] had a terrible problem with one person in particular,” Brother Arnold said. “I really had it. I went to Brother Ted and said, ‘I can’t do it anymore. I can’t stand him; I can’t live with him. So I don’t see any other choice but to leave because he’s not going to leave.’ Brother Ted sat me down and said the most profound thing anyone has ever told me. He said, ‘You’re looking at this all wrong. You don’t have to like him. You don’t have to like anybody. You just have to love him, and you have to love everybody. We get these things mixed up in our minds. It’s easy to think that loving is more important than liking, or that it’s part of the liking. Not at all. They are very different.”

Along with being utopians, the Shakers were also inventors. They invented hundreds of labor-saving devices, including the flat broom, circular saw, and clothespin. They refined the iconic oval box with wraparound “swallowtails,” so that the wood could expand and contract according to the seasons without cracking. They shaped the direction of American architecture and furniture design with their innovative details and sparse lines. Everything they made was designed with such intention and singularity of mission, embodying Mother Ann Lee’s most famous saying: “Hands to work. Hearts to God.”

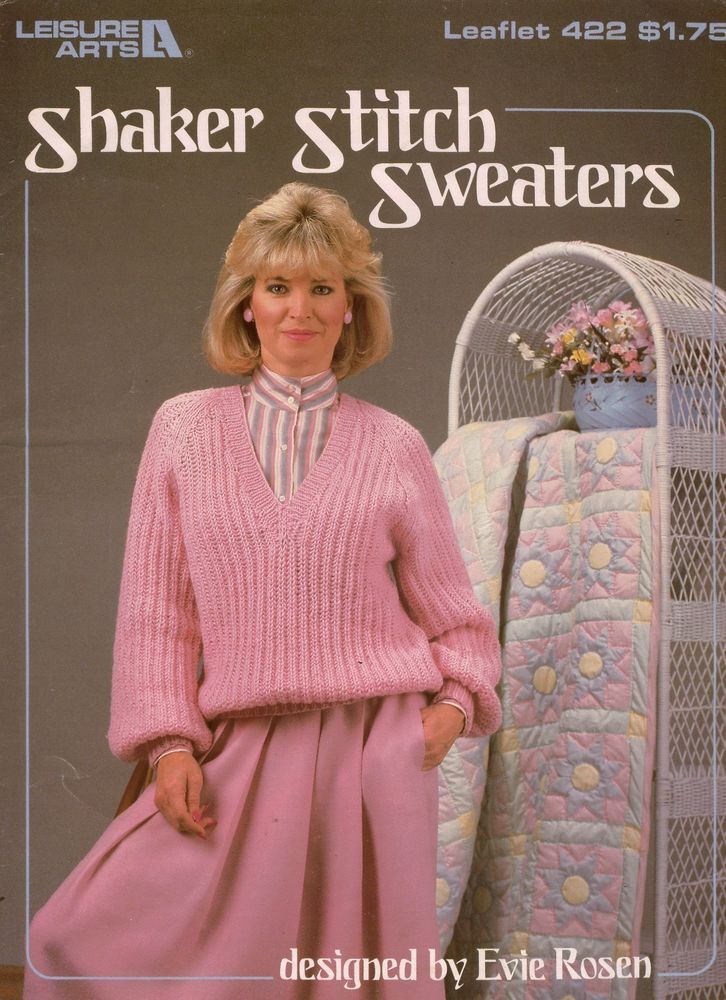

The Shakers also left an imprint on American style. Shaker women were prolific knitters, creating large numbers of mittens, washcloths, stockings, socks, and shawls. And among those items was the Shaker sweater: a derivation of the fisherman’s rib, this two-row repeat knitting pattern is defined by evenly spaced ribs that look slightly different on the facing and reverse sides. Some of these sweaters were made for members of the community. Others were sold to non-Believers, who visited Shaker communities during worship services, and then bought Shaker crafts and sweaters afterward. That’s how this iconic knit became known to many Americans as the Shaker sweater.

“According to Brother Arnold Hadd, lead Shaker and historian at Sabbathday Lake, Maine, the Shakers invented the Shaker stitch,” Brother Arnold tells me. “He believes that it originated in Canterbury, New Hampshire during the 19th century. As production increased and technology advanced, the Canterbury and Enfield Shakers in New Hampshire had commercial knitting machines designed to replicate the Shaker stitch for the production of sweaters and socks. The business thrived into the 20th century. Examples of Shaker stitch knitting machines remain on display for demonstration at both New Hampshire Shaker Museums.”

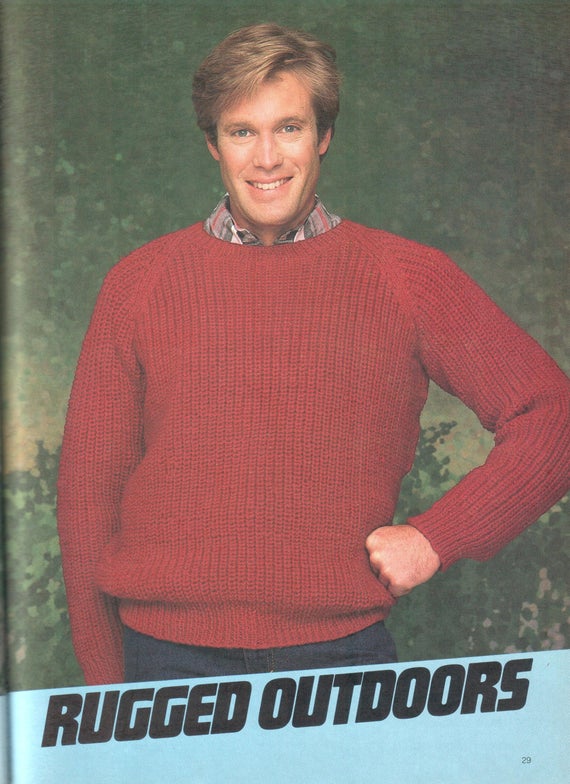

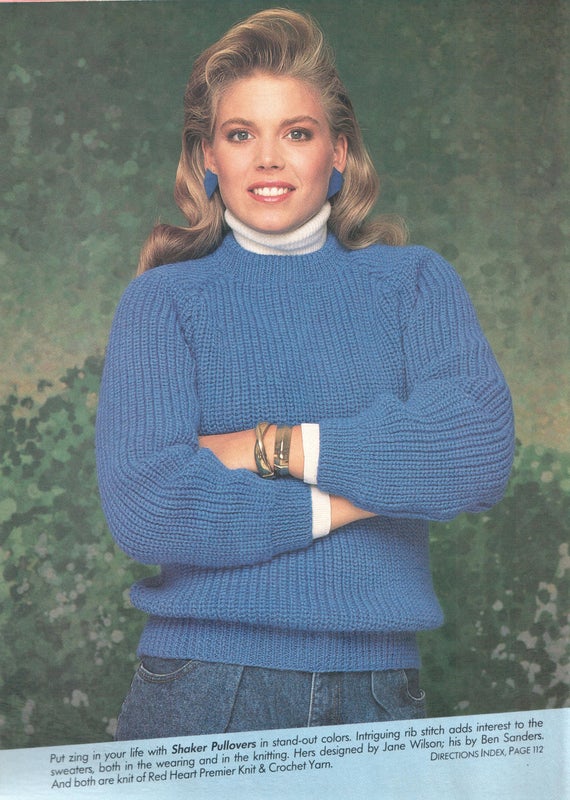

I think of the Shaker sweater as this nation’s most iconic knitwear invention. It’s the sweater of lost American accents, 1980s movies, and old clothing catalogs from LL Bean and Orvis. When I close my eyes and imagine a stretched out, slouchy cotton knit worn somewhere in New England, paired with washed denim jeans and muddy LL Bean boots, I imagine the Shaker sweater in all its glory. In my neighborhood, women wear them with liner jackets, wide-legged pants, and black Blundstones. It’s the sweater of coffee shops and farmers’ markets. Like grenadine neckties, they’re an easy way to add texture to simple outfits, while also toning down patterned ensembles. You can layer a Shaker sweater underneath a leather jacket, denim trucker, rounded bomber, French chore coat, or an oversized topcoat. It goes with everything.

Interestingly, some of the themes in American knitwear history can be seen abroad, suggesting that there’s perhaps something inherent in the act of knitting clothes. Mahatma Gandhi’s portable spinning wheel, known as a charkha in Hindi, was a symbol of the Indian independence movement. In the early 1930s, Gandhi used one to spin his own yarn and make his own clothes while he was being held as a political prisoner. He later encouraged other Indians to take up the spinning wheel in their effort to shake off the yoke of British imperialism, establish economic independence, and recognize the intersection between spirituality and daily work.

“Despite originating from distant geographies, there are many parallel expressions of non-violence in both Shaker and Gandhian traditions,” says Mia Morikawa of 11.11. “Both share a visual language distinguished by the simplicity of form, harmonious design, craftsmanship, and utility. Shakers were essentially early advocates for mindful living through service and the practice of craft. Gandhian philosophy emphasizes small unit production and agriculture, as opposed to large-scale industrialism, and the decentralization of economic structures through self-contained villages and cottage industries. Their back-to-the-land legacies involve the timeless idea of cultivating freedom through self-sufficiency.”

11.11 recently joined hands with The Tatter Blue Library to create a small line of fully handknitted sweaters made from handspun yarns dipped in natural indigo. While slightly different in design than a true Shaker knit, the sweaters embody much of that same slow-living spirit. As part of their crowdfunding campaign, they also sold skeins of indigo yarn, so that knitters can make their own sweaters at home. “We think hand-loomed fabric is an alternative to fast fashion,” Morikawa says. “Our handspun yarn and handmade sweater draw on non-violence as a mindset. It is an opportunity to include in your crafting practice in allyship with a system that centers these communities as part of a better supply chain. Hand spinning communities have some of the smallest carbon footprints on the planet and have preserved the art of hand twisting fiber into yarn. The self-soothing, tender quality in the practice of hand knitting is a meditation in motion and feels like the kind of healing we need right now.”

The crowdfunding campaign is going on until the end of March. You can get skeins of handspun yarn starting at $40, handknitted berets starting at $70, and handknitted sweaters starting at $360. Since these are pre-order items, you’ll save a little money, so long as you’re willing to wait a couple of months for delivery. On 11.11’s website now, you can also find similar sweaters that have been naturally colored with sappan woods and tamarind seed solutions.

You can find Shaker sweaters at many mainstream, classic American clothiers nowadays, such as LL Bean, Lands’ End, and Brooks Brothers. They’re also stocked at smaller companies, such as The Vermont Country Store and Sid Mashburn. Cotton versions will stretch more easily than wool, and since the Shaker stitch is already a bit stretchy, you have to be comfortable with a slightly stretched out knit if you get a cotton one. This StyleForum member is also selling the cashmere Eidos Shaker sweater I mentioned above. A size medium in that sweater can fit a true medium or a small, depending on how you like your knitwear to fit.

The Shaker stitch is also a derivation of the fisherman’s rib, and thus often referred to as a half-fisherman rib. The main difference is that the fisherman’s rib looks identical on both sides (the facing and reverse), while a Shaker stitch looks slightly different. For this reason, it can be hard to tell what is a true Shaker sweater and what’s a fisherman’s rib online. But for all intents and purposes, the two will look nearly identical when worn. You can find fisherman rib sweaters at Andersen-Andersen, Inis Meain, De Bonne Facture, Private White VC, Los Angeles Apparel, Aran Crafts, Batoner, Anderson & Sheppard, Phlannel, and The Croft House. Colhay’s, an advertiser on this site, sells beautifully ribbed rollnecks made from a 4-ply, 8-gauge cashmere. The company loaned me one last year and I was impressed with its weight and softness. The fit is a bit trimmer than most Scottish-made knitwear, although I think it looks best sized up.

Alternatively, you can get a sweater made with a half-cardigan stitch, which has a similar texture, but isn’t ribbed. GRP, Stephan Schneider, Luca Faloni, Sunspel, and Mr. Porter’s in-house line all utilize the style. Brut Clothing, a vintage clothing store in Paris, has USN deck sweaters with a similar texture. American Trench sells cardigan stitch beanies. One of my favorites in this category is 3sixteen’s simple, black crewneck sweater, which is a useful layering piece since black knitwear can serve as a neutral background for outerwear. “We went with a half-cardigan stitch on this because it has more body and doesn’t stretch as much,” says 3sixteen co-founder Andrew Chen.

Pictured below are some Shaker sweaters, fisherman rib sweaters, and half-cardigan stitch sweaters, along with the kinds of things I like wearing with them. Fundamentally, they go with basically anything because solid-colored knits with texture add visual interest without being overwhelming. But they work exceptionally well with workwear, shabby chic outfits, and anything with utilitarian roots.