In 2008, a StyleForum member shared photos of a bespoke shirt they had made by the renowned Neapolitan shirtmaker Anna Matuozzo. Though the images have since been lost to time, they showed a blue-and-white Bengal-striped dress shirt made from Carlo Riva cotton, featuring a semi-spread collar and some extraordinary details. The buttons were firmly shanked, the sleevehead and yoke showcased delicate shirring, and fine, nubby topstitching traced the seam running along the shoulder—all hallmarks of careful hand tailoring. At the time, the price for such a shirt—bespoke, cut from an adjusted block pattern, and crafted with the highest degree of handwork—was 350 Euros. The price was considered so stratospheric at the time that it sent several forum members reeling. One distinguished member with decades of bespoke experience questioned the rationale behind spending so much on a dress shirt. “If an errant meatball rolls down your body, it’s done,” he cautioned.

I was reminded of this painful lesson last year while getting dressed. A decade of dipped garlic naan and Vietnamese spring rolls rolling down my gullet has nudged me up a size. Unlike jackets, shirts don’t have seam allowances, so I’ve had to rebuild my shirt wardrobe. A few weeks ago, I published a post about which shirts I find useful in a tailored wardrobe; this one is about casualwear.

Like my “Excited to Wear” posts, this series is full of personal prejudice. Over the years, I’ve found that dry, generic lists of “wardrobe essentials” are rarely useful or interesting. What I enjoy reading most are people’s unapologetic opinions on clothing. That said, casualwear presents a unique challenge. Unlike traditional men’s tailoring, which follows a relatively narrow set of conventions, casual dress is vast and varied. Much of what I’ll cover here will only resonate if you, like me, enjoy dressing like Bob the Builder. Still, I hope you find one or two things worth considering.

The Plaid Flannel

The television show Outlander opens with a haunting theme song, which riffs on the melancholic lyrics of an old Scottish ballad: “Speed bonnie boat, like a bird on the wing; Onward! the sailors cry; Carry the lad that’s born to be King; over the sea to Skye.”

The ballad refers to the dramatic escape of Charles Edward Stuart, a dashing but doomed prince who ignited Scotland with dreams of Stuart restoration in 1745 when he led a daring march deep into England. Charles reached Derby before his Jacobite army suffered a crushing defeat at the Battle of Culloden, forcing them to retreat. In the months that followed, Charles was Britain’s most wanted man, carrying a £30,000 bounty on his head as he fled into the mist-veiled Western Highlands, where he moved between caves and cottages, always one step ahead of his pursuers. On the remote island of Benbecula, Jacobite sympathizers convinced Flora MacDonald to risk everything to help spirit the rebel away. She arranged for him to dress in a petticoat, bonnet, and gown, transforming the fugitive prince into a humble maid, Betty Burke. Concealed in this disguise, he escaped to the Isle of Skye, before eventually fleeing to France aboard a frigate, cementing himself as a romantic Scottish hero who’s remembered as Bonnie Prince Charlie, the Young Pretender.

Fearful of another Scottish uprising, the British government enacted the Dress Act the following year, which banned the wearing of traditional Highland dress, including tartans. “No man or boy within that part of Britain called Scotland shall, on any pretext whatsoever, wear or put on the clothes commonly called Highland Clothes, that is to say, the Plaid, Philibeg, or little Kilt, or any part whatsoever of what peculiarly belongs to the Highland garb.” For the first offense, the punishment was six months in prison. For the second offense, the punishment was harsher: seven years of exile in one of the British colonies, such as the Americas, later known as the United States (shudder).

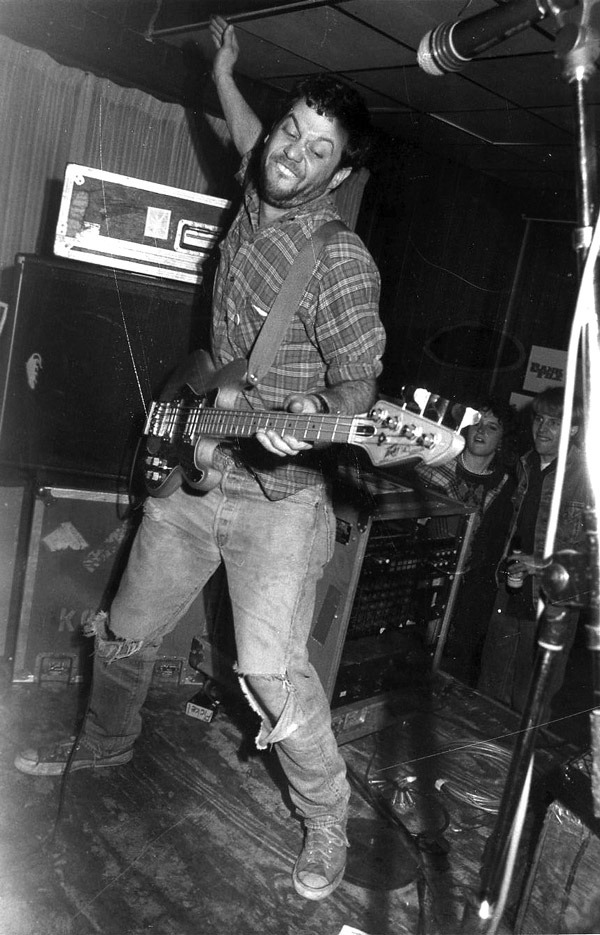

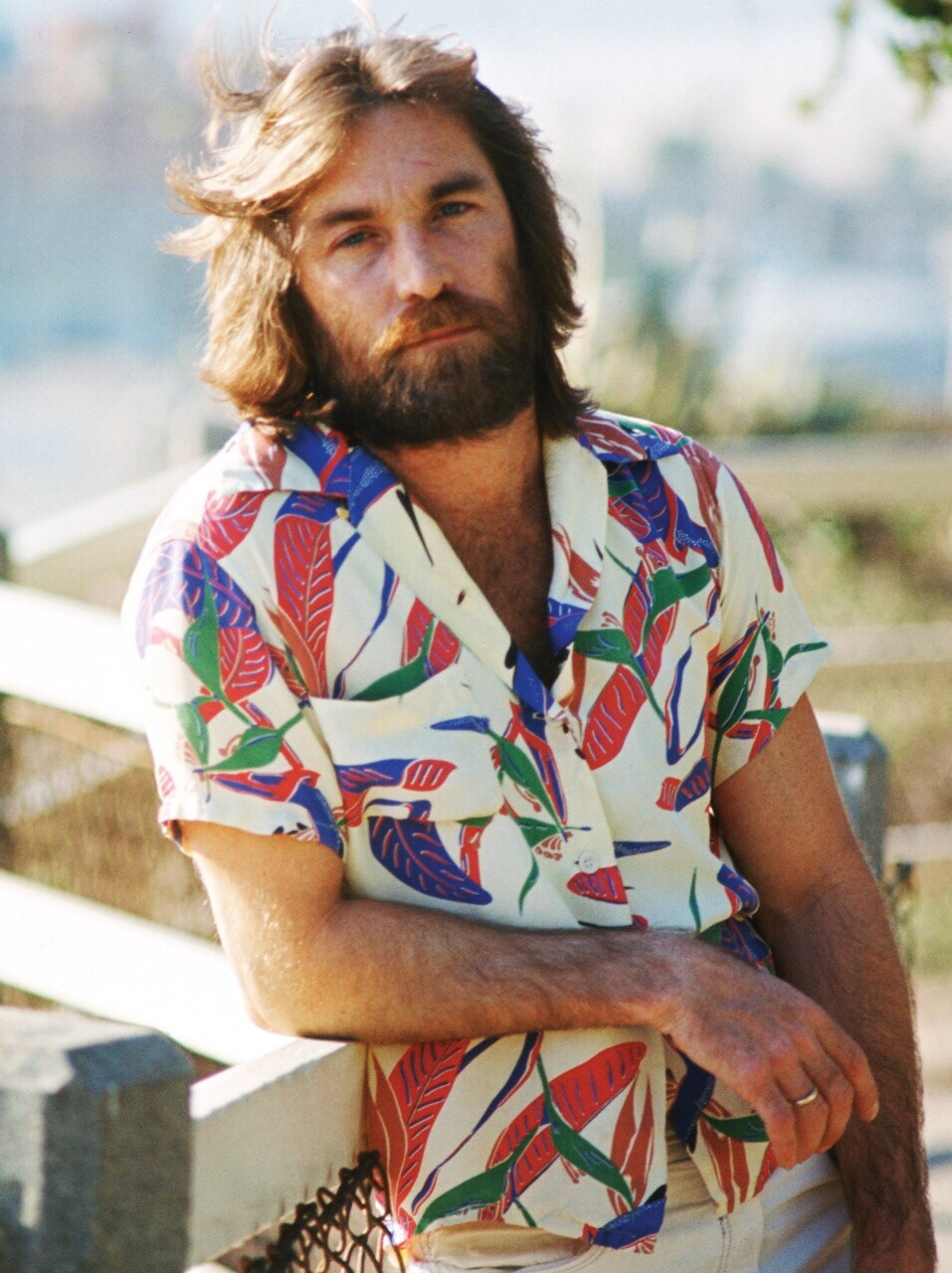

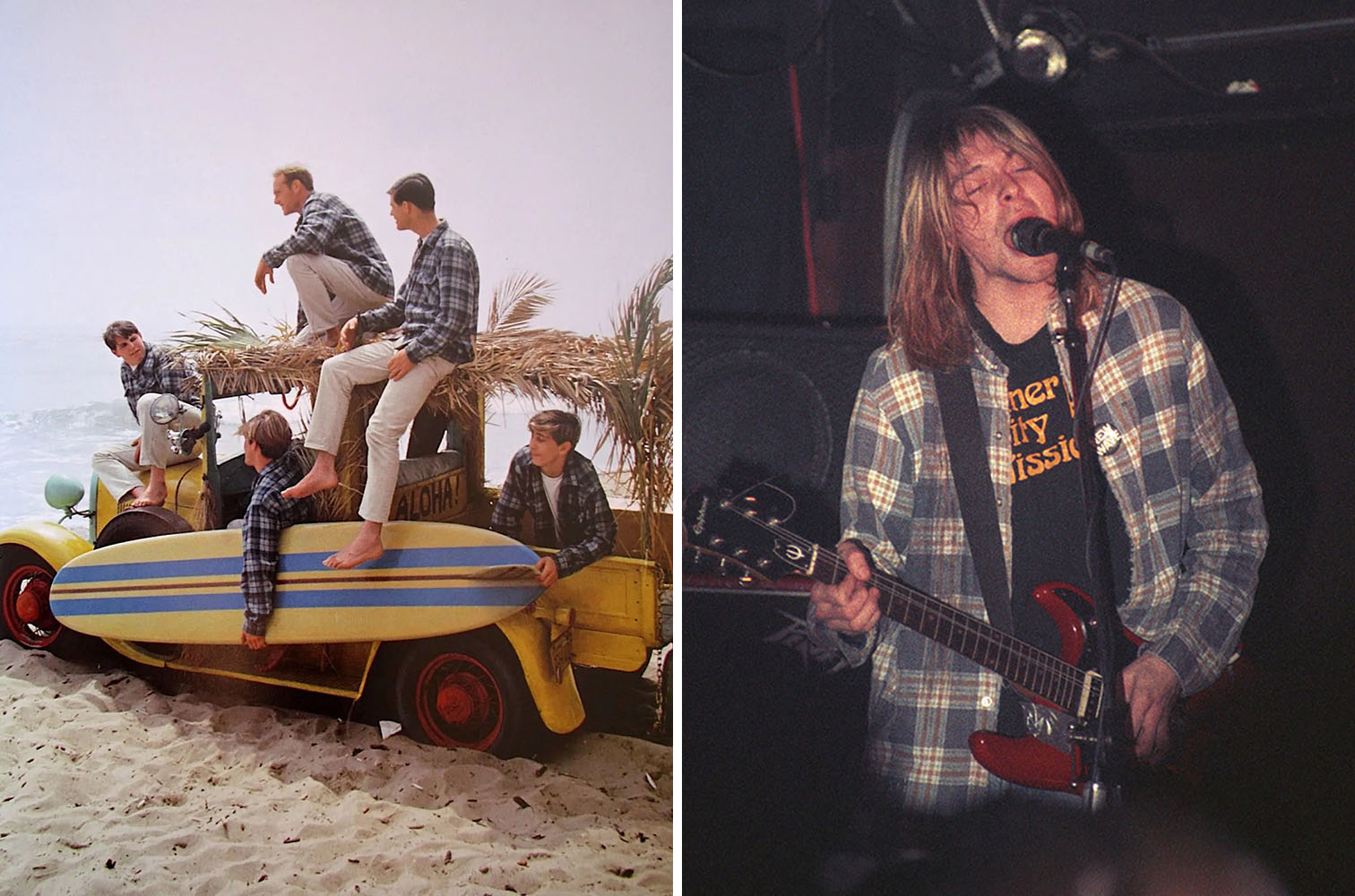

The Dress Act was finally repealed in 1782, as the Jacobite threat faded and the British government sought to mend its fractured relationship with Scotland. Yet, I’ve often wondered if that moment marked the beginning of when plaid became associated with the rebellious working classes. Over the following centuries, plaid migrated from the shoulders of Highland warriors to the backs of Welsh farmers, European laborers, and eventually, American outdoorsmen, surf bums, and countercultural rebels. In 1850, Pennsylvania-based Woolrich Woolen Mills trademarked Buffalo plaid, a bold red-and-black check that, over time, became an unofficial uniform for American hunters and loggers. A century later, the Pendletones—soon to be known as The Beach Boys—helped popularize the Pendleton Board Shirt, which surfers originally used as a quick cover-up upon leaving the shores of Southern California. By the close of the century, figures such as Kurt Cobain made this humble pattern into a symbol of rock rebellion.

About five years ago, I interviewed 3sixteen co-founder Andrew Chen about how his personal uniform has evolved over the years. He said he’s always worn the same things—hoodies, sweats, flannels, t-shirts, and jeans—but has dialed in on what he likes. “Pick one part of your wardrobe and go learn about it,” he recommended. “Check out high-end shops, low-end shops, and vintage shops. Once you’ve tried enough things, you’ll know what you like. When I pick up a mass-produced flannel and compare it to something of higher quality, the difference is obvious. I won’t spend money on a cheaper flannel because I know I’ll never wear it. I’d rather have a more expensive flannel that makes me feel good every morning.”

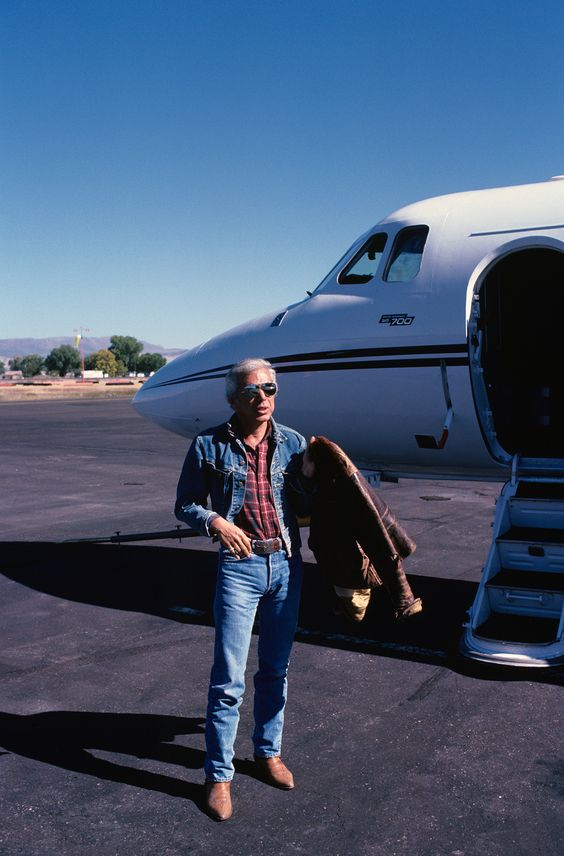

I prefer flannels that feel like they were made before the 1980s. That means fabrics with texture and depth: slubby, looser weave, coarser yarns, rich mélange colors, or “triple yarn” constructions where individual threads visibly stand out. I also look for the details that defined mid-century work shirts: cat-eye buttons, runoff stitching, and a slightly shortened spread collar. As for color and pattern, I’m open to anything interesting, although I’ve found that overly classic designs, such as buffalo plaid, tend to go unworn. These days, my favorite flannels come from RRL, although there’s no shortage of good options (including affordable vintage). I think it’s worth getting a small stack in staple colors—blue, green, tan—and in different weights for the various seasons.

Options: RRL (I recently bought this and like it), Polo Ralph Lauren (great quality and design without the RRL price), Wythe, The Real McCoy’s, Todd Snyder, 3sixteen, Samurai, Flat Head, Iron Heart Ultra Heavy Flannels (these wear more like jackets, size up), UES, J. Crew (the Wallace and Barnes stuff was a great value, but now only on eBay), Gitman Vintage, The Vermont Flannel Company, and Portuguese Flannel (for something dressier). For vintage, call Wooden Sleepers or look up Big Mac, Five Brothers, Big Yank, and Frostproof on eBay. For custom, try Proper Cloth.

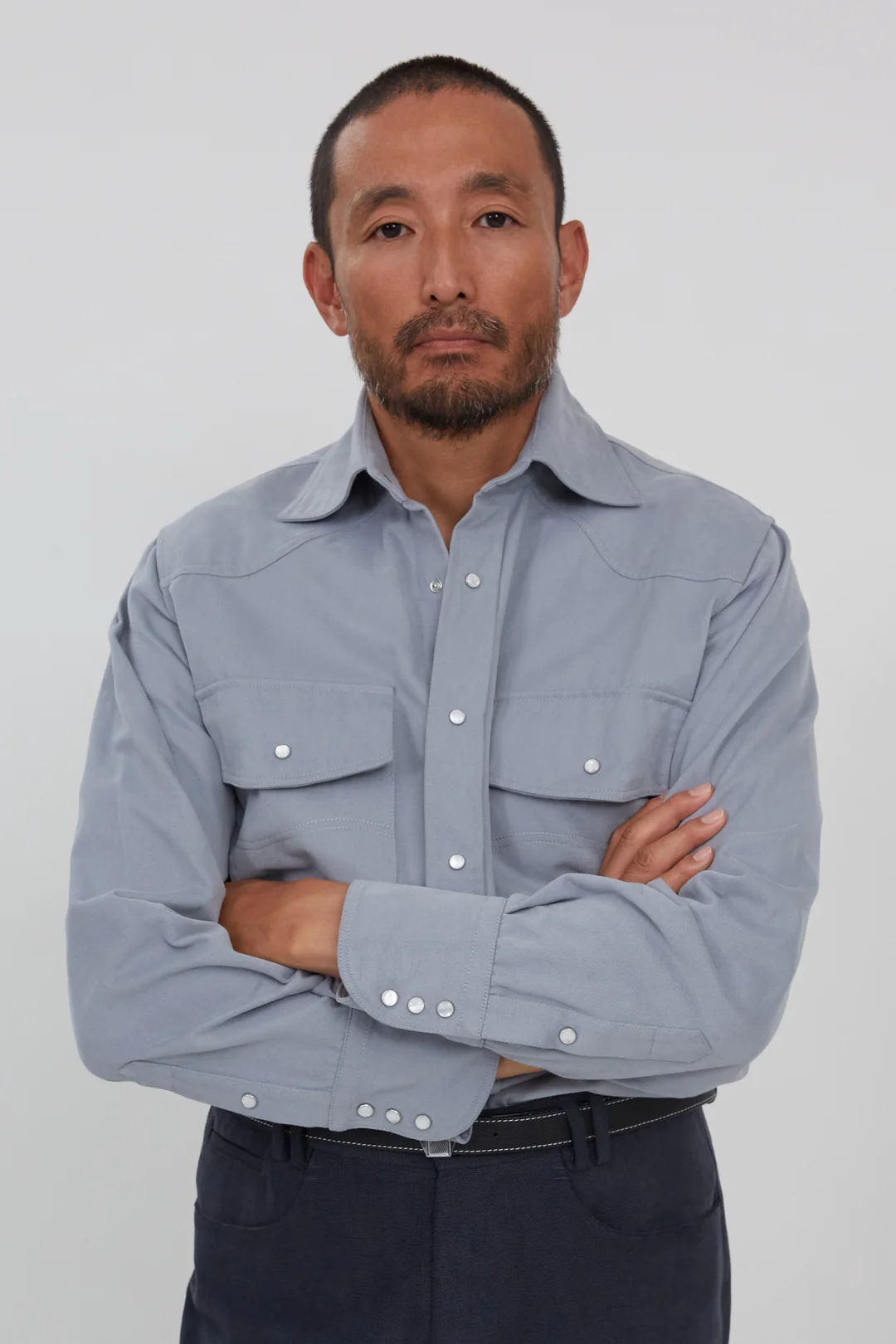

The Western Shirt

When John E. Brooks asked his New York tailors to replicate a collar style he had seen on English polo players in the 1890s, he unknowingly set the foundation for what would become a defining element of classic American dress. The button-down collar—first introduced in cotton cheviot before transitioning to oxford cloth—soon became the go-to pairing for sack suits and penny loafers. For much of the 20th century, it was worn by Ivy League students, Italian industrialists, Black jazz musicians, Pullman-riding executives, and even radical critics of the American bourgeoisie. I’ll always love oxford cloth button-downs because they embody mid-century style.

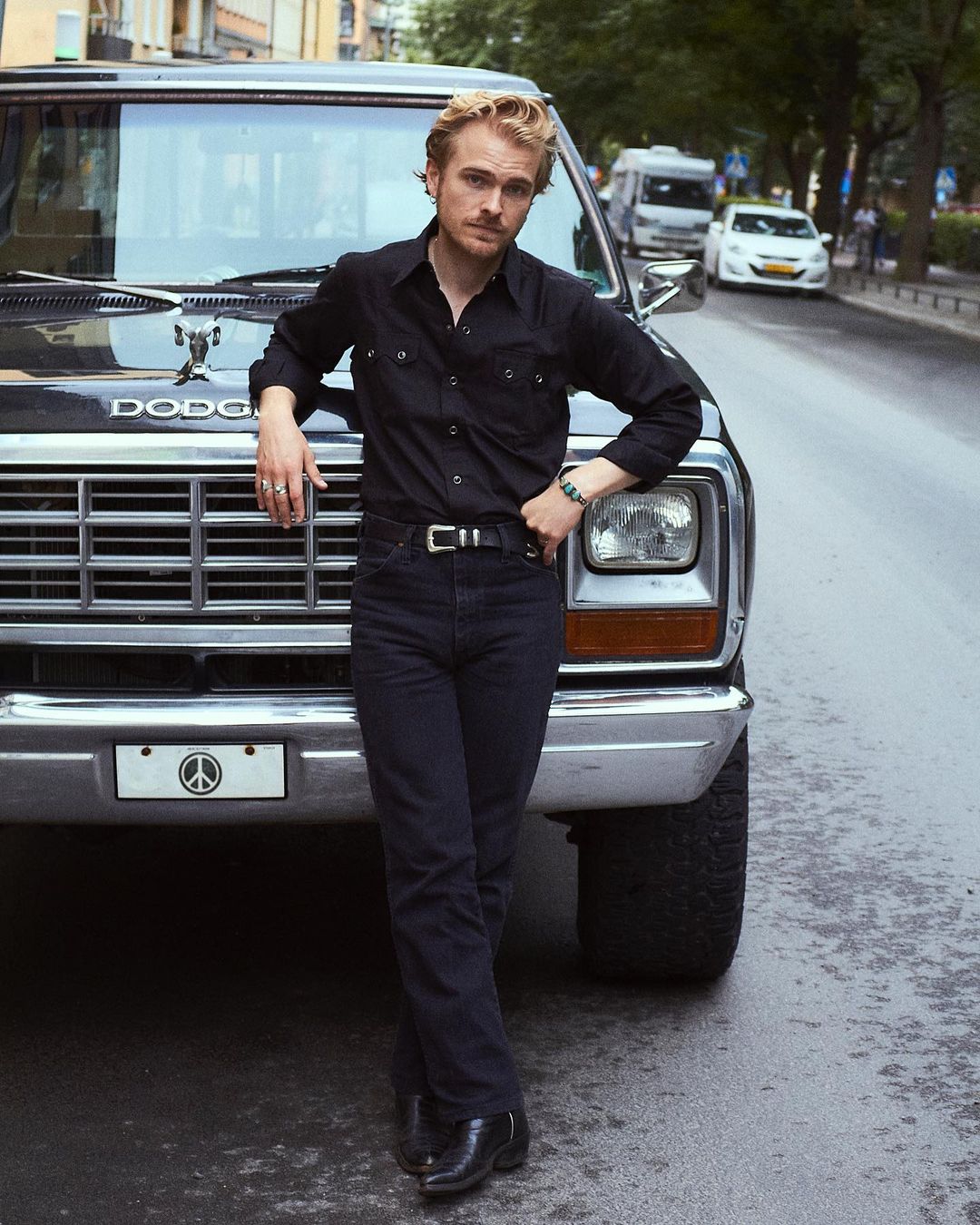

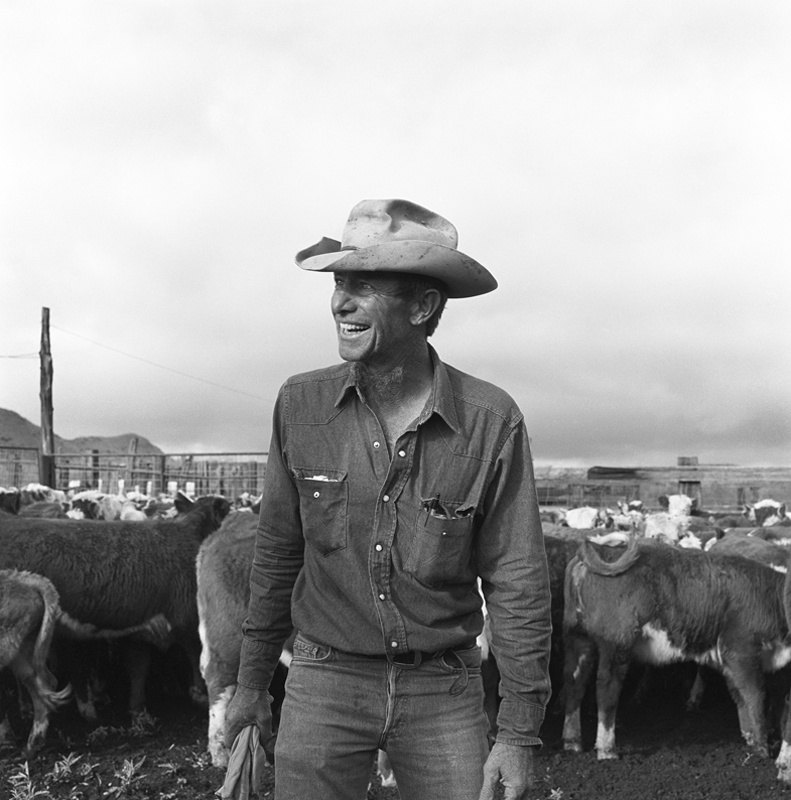

Over the past decade, I’ve come to appreciate America’s other button-down: the snap-button Western shirt, a staple Jack A. Weil introduced at his Denver-based store, Rockmount Ranch Wear, in the years following World War II. At the time, cowboys wore standard button-up shirts, but buttons could be impractical—slow to fasten, prone to breaking, and, in the worst cases, a potential hazard if a rider got caught on a rope or fence. Weil reimagined the cowboy shirt with quick-release, diamond-shaped snaps that wouldn’t break or go missing. If oxford cloth button-downs defined mid-century America’s intellectual and financial elites, then Western shirts were the uniform of ranch hands and rodeo cowboys across the country’s rural landscapes.

“I’ve had quite a few vintage Western shirts, but the old Rockmounts and Short Horn Levi’s are my favorites,” Ethan Newton of Bryceland’s once told me. “I’ve hunted down quite a few H Bar C shirts in different cloths, and some unusual rayon or wool gabardine versions from Prior Denver. I think there’s a real beauty to old westernwear, from Acme Pee Wee boots to Lee shirts. There’s a lot of decorative detailing that makes them feel joyous. I also like the showy elegance: a long collar point to support a printed silk tie, a higher armhole to pair with a tailored jacket, and long tails to keep it tucked in. There is a utility to them that belies their elegance.”

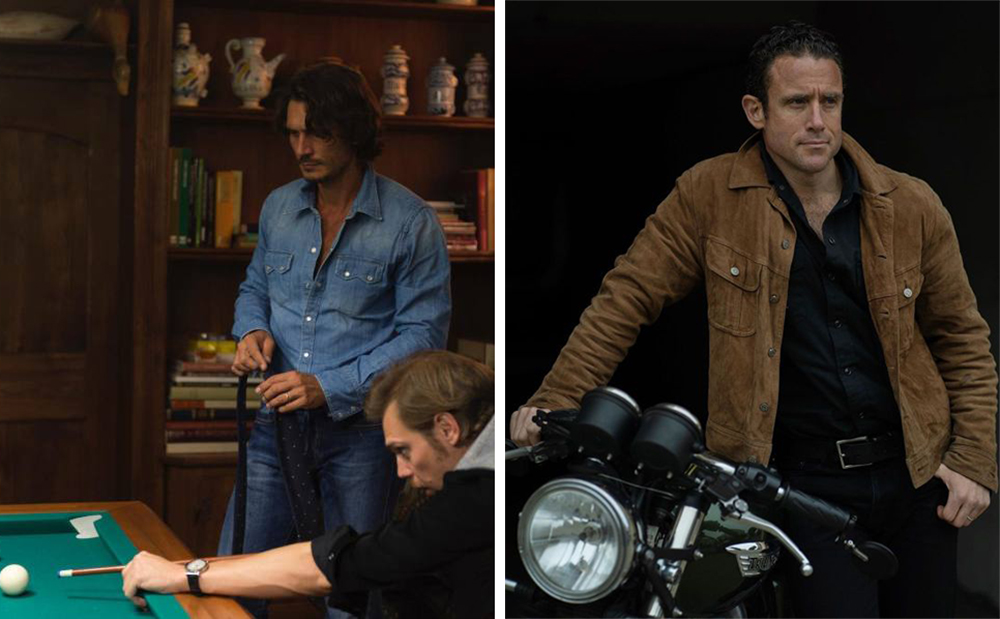

Ten years ago, I bought my first Western shirt after seeing Agyesh Madan, founder of Stoffa, wearing a Wrangler shirt with peached cotton trousers, a suede bomber, and some well-worn Belgian loafers. The outfit struck me, so I tracked down the same stonewashed shirt. In the years that followed, I wore that shirt so much that I ended up collecting others in various materials—raw denim, lightweight chambray, ribbed needlecord, brushed flannel, and fluid fabrics such as Tencel, silk, and gabardine. I love Western shirts because they symbolize that mythologized American character centered on pragmatism, optimism, and rugged individuality.

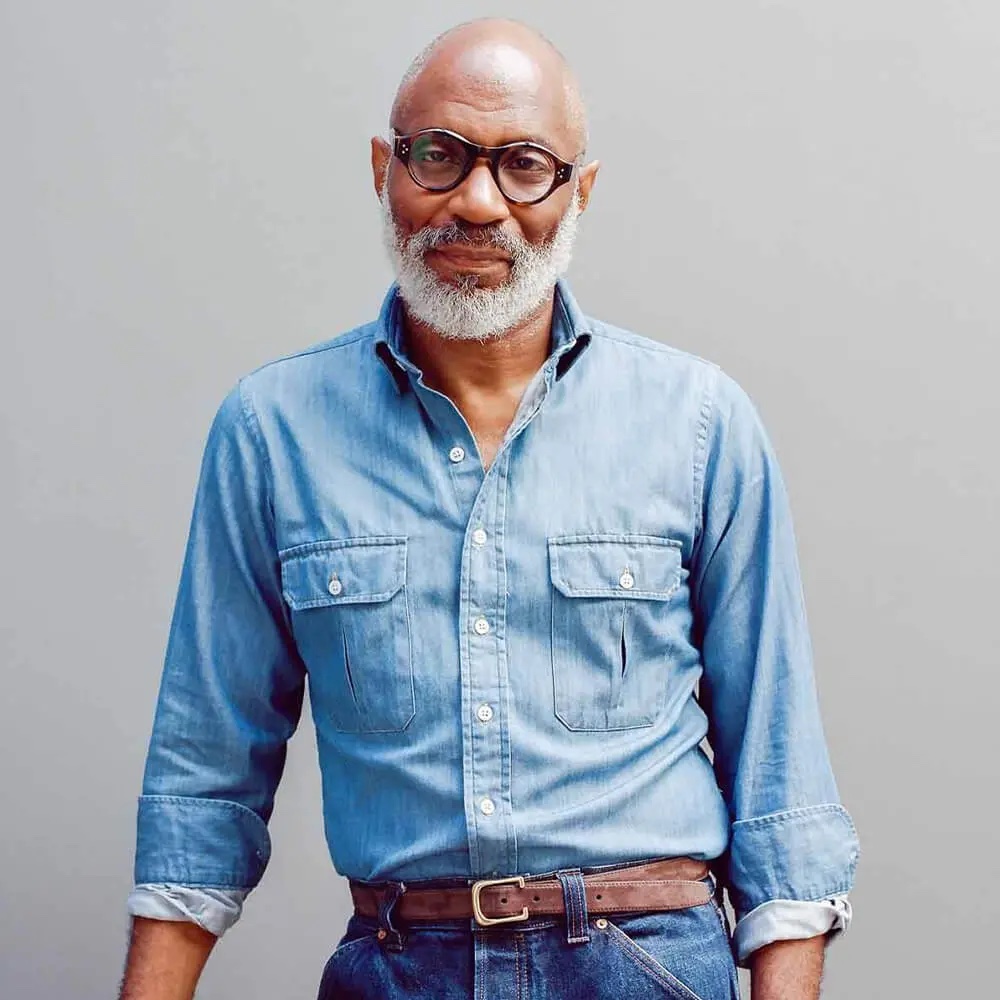

If you’re getting your first one, start with the basics: something in blue denim. You can wear this with tailored tweeds, cotton suits, and casual pieces such as trucker jackets, bombers, and olive fatigues. I think denim-on-denim looks great, but if you’re worried about looking like Justin Timberlake, vary the color of your jeans. A blue denim Western shirt can be teamed with jeans in black, tan, and off-white. Wrangler’s stonewashed denim shirt remains affordable at just $40. However, my favorite is this unembellished raw denim design from Kapital (the oversized fit is forgiving to dad bods if you size down). Wear a denim Western shirt until the collar frays and your elbows bust through the sleeves—it looks better that way.

If you, like me, find denim Western shirts useful, consider getting something in another material: needlecord or moleskin for winter, and then Tencel and chambray during the warmer months. Post Romantic, an advertiser on this site, can make made-to-measure silk Western shirts for about $110. When shopping for a Western shirt, consider the details, such as the shape of the snaps (diamond versus round), front yoke (slanted or pointed), and pockets (sawtooth, slanted, or teardrop). If you’re daring, you can also explore embellishments, such as embroideries and piping. Although, I have to admit that I tried one of those last season and felt like Howdy Doody.

Options: Wrangler, Kapital, Post Romantic, Bryceland’s, Rubato, Wythe, Jake’s London, Todd Snyder, RRL, Polo Ralph Lauren, Buck Mason, Tonywack, Sid Mashburn, Nudie, Isabel Marant, Carter Young, Spier & Mackay, J. Crew, and Levi’s. For custom, check Proper Cloth and Dixon Rand (Proper Cloth has washed denim fabrics that would be perfect for this sort of thing). Also, check shops such as Self Edge, Standard & Strange, Canoe Club, Division Road, and Rivet & Hide,

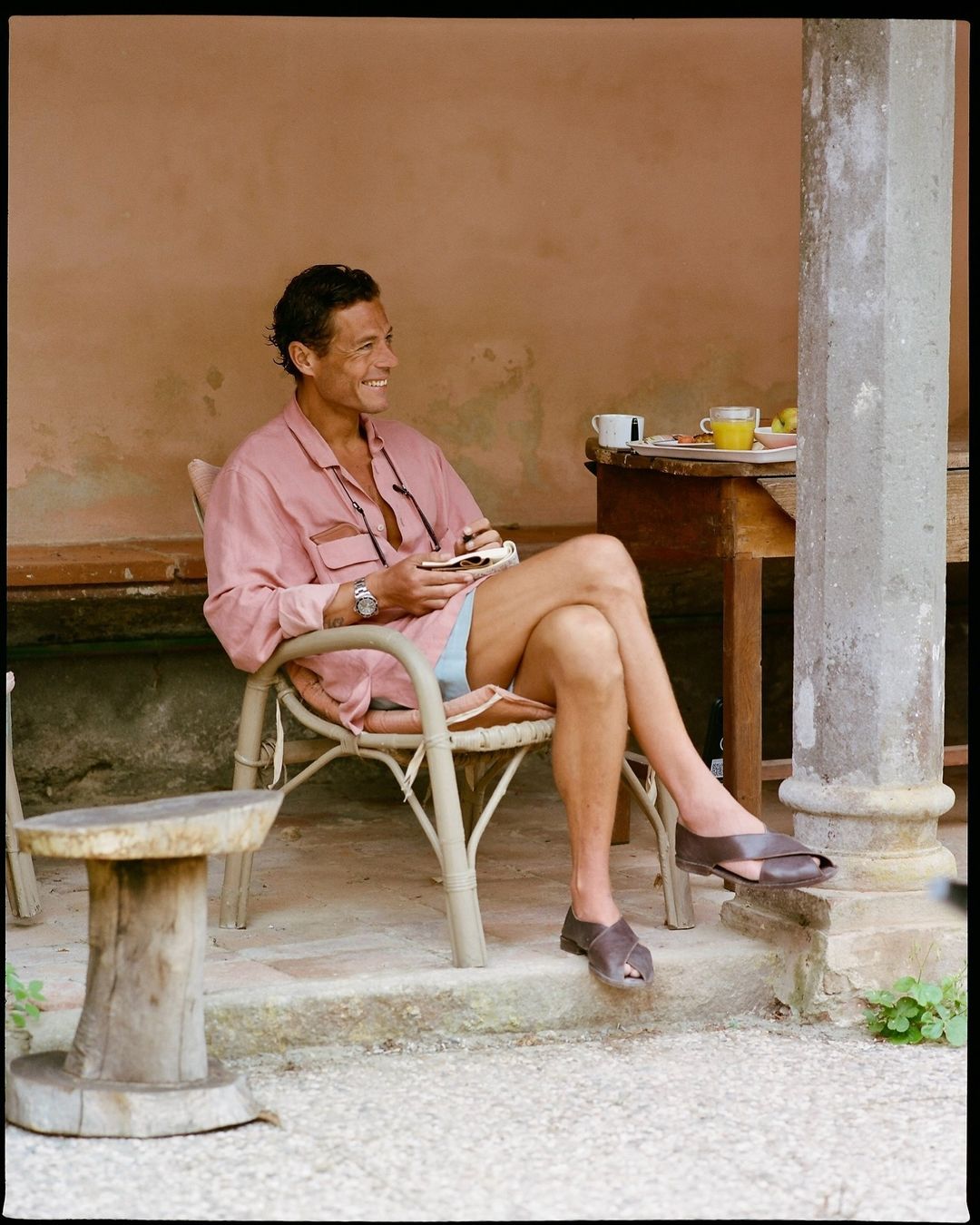

The Camp Collar Shirt

There are two reasons why menswear can feel uninspired during the warmer months. The first and most obvious is the lack of layering. Outerwear gives structure, shape, and visual interest to an outfit in ways a simple dress shirt or t-shirt rarely can. The other reason is that we derive many of our style norms from Britain, a tiny, damp island where summer is more of a rumor than a reality. The British gave us gray flannel suits, prickly Harris tweeds, and spongey Shetland knits. If not for Neapolitan cutters like Vincenzo Attolini, who took all the stuffing out of British suits, wearing tailoring half the year would feel like sealing yourself in a woolen tomb. New England prep hasn’t been much use, either. Without a tailored jacket, Ivy Style outfits teeter dangerously close to business casual.

For summer style inspiration, it helps not to mistake Anglophilia for universal style wisdom. Plenty of countries have mastered the art of dressing for temperatures soaring past 90 degrees. On my desk, there’s a framed photo of my parents in Vietnam, taken a few years before they fled during the war. My father stands beside my mother, wearing a boxy camp collar shirt and neatly tailored trousers, a typical uniform among Southeast Asian men at the time. Other warm regions had versions of this look: the guayabera in Cuba and the Aloha shirt in Hawaii. In every case, these shirts were loose, breathable, and designed for the heat, their airy fabrics and soft, unstructured collars offering both comfort and style.

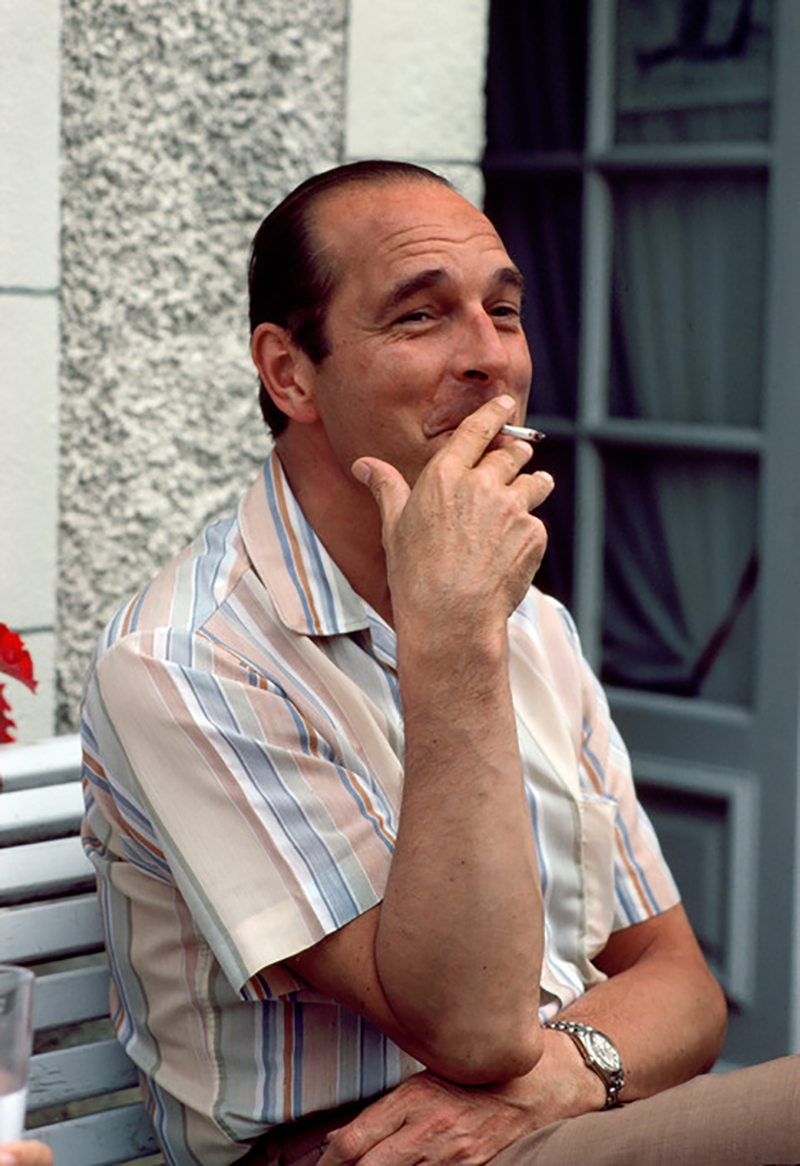

For a time during the mid-20th century, these shirts represented something more than just physical relief. Just as button-down collars symbolized professionalism and education, the camp collar became a marker of a life spent unhurried. It thrived in places built for leisure—Palm Springs, Miami Beach, the French Riviera—where men sipped long cocktails while wearing canvas espadrilles and linen trousers, never too fitted. Elvis Presley wore one in Blue Hawaii (1961), lounging by the shore with a ukulele in his hands. Sean Connery’s James Bond wore a dusty pink camp collar shirt with teeny tiny shorts as he wandered through the Bahamas in Thunderball (1965). There’s a photo of Dr. Martin Luther King standing in front of his library, looking as cool as ever, wearing a camp collar shirt tucked into high-waisted trousers secured with a thin dress belt.

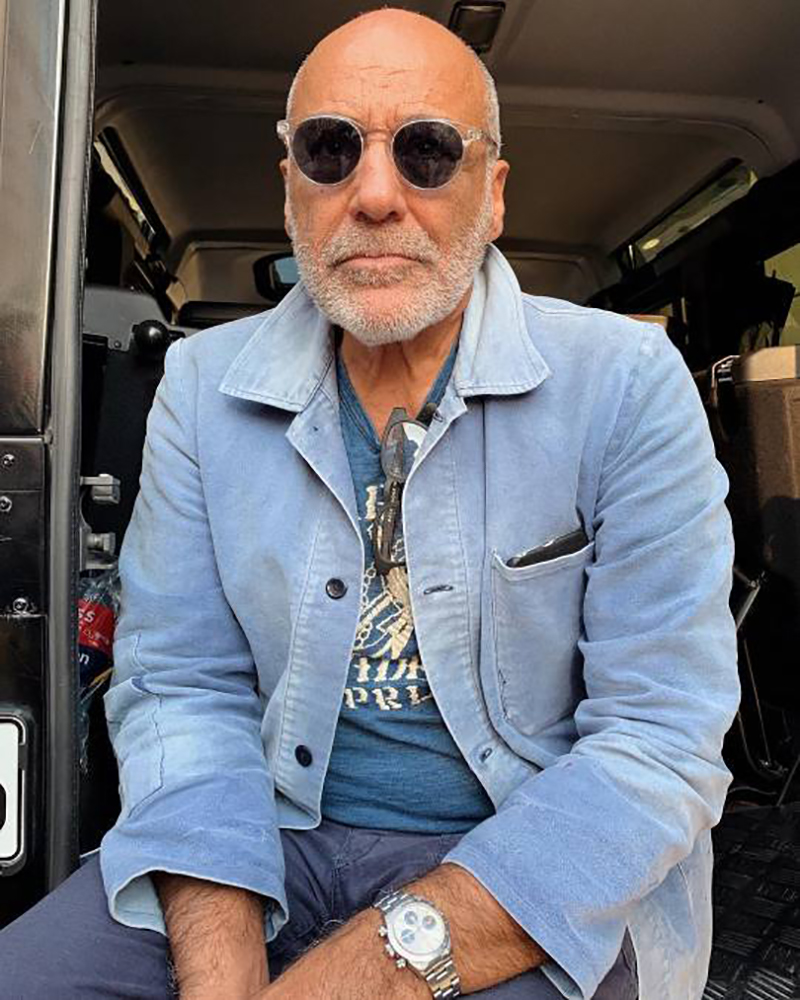

I’ve come to see the camp collar shirt as a summer essential. It’s an easy match with shorts but looks just as good with olive fatigues or blue jeans, adding a little character where a basic button-up might fall flat. When layering isn’t an option, it helps if your shirt and trousers have some personality. A camp collar shirt shines in bold patterns and interesting fabrics, whether it’s the breezy feel of linen or the fluid drape of silk. A few years ago, I picked up a cream-colored silk shirt from Post Romantic, inspired by a Umit Benan design I admired but couldn’t justify at full price. The Post Romantic version was just $110—a steal for a made-to-measure shirt. Pieces like this pair well with understated accessories—a necklace, a vintage bracelet, oversized sunglasses—details that add visual interest without bulk or heat. For summer style inspiration, just look at mid-century photos of how men dressed around Cuba and the Mediterranean.

Options: Portuguese Flannel, G. Inglese, Wynona, SK Manor Hill, Jake’s London, Bryceland’s, Séfr, Kartik Research, Kardo, Frescobol Carioca, Corridor, 3sixteen, Sun Surf, Róhe, Commas, Todd Snyder, Buck Mason, Industry of All Nations, Spier & Mackay, and J. Crew. Again, for custom, try Proper Cloth.

The Soft Chamois and Chambray Shirt

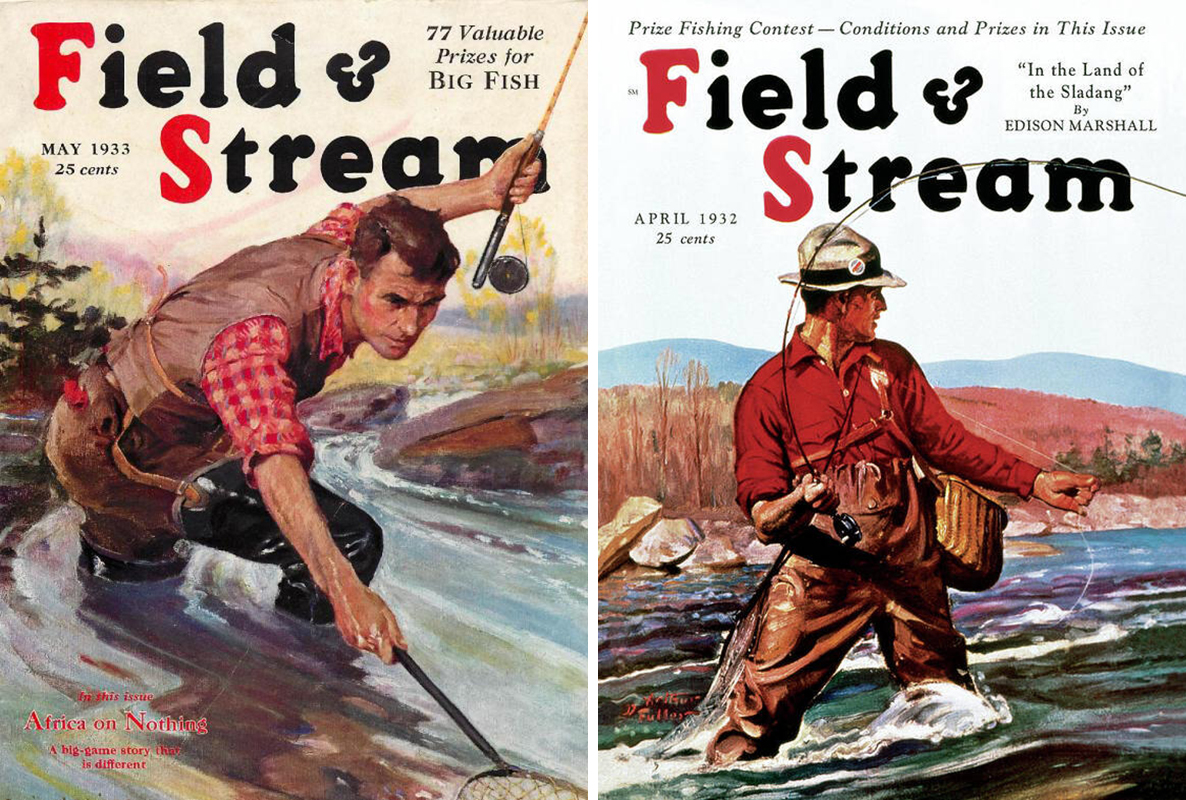

On eBay, you can find mid-century copies of L.L. Bean’s famous mail-order catalogs. Sandwiched somewhere between listings for Maine duck boots and Norwegian knits, there are pages devoted to the company’s thickly napped, 7oz cotton shirts—originally called leatherette shirts before they took on the name chamois. The term chamois comes from the soft, pliable leather made from the hide of the Alpine chamois goat (and later goatskin). You may have seen it in your parents’ garage, as chamois leather is prized for its ability to leave cars streak-free after a wash. In the 1920s, Mr. Bean adapted the cotton version into a wind-resistant, warm, and durable shirt suited for hunting and fishing. Throughout much of the 20th century, campers and Midwestern college students paired them with 60/40 mountain parkas, five-pocket cords, and pull-up leather camp mocs.

Though chamois shirts have never been a staple in my wardrobe, I appreciate them on cold days. With a soft, velvety texture reminiscent of a well-worn billiards table, they feel incredible in the winter. Whether it was the result of L.L. Bean’s uncanny design instincts or, as Pierre Bourdieu might argue in Distinction, the way their clothes gained meaning through the people who wore them, chamois shirts seem to look best in their original Crayola hues: fern green, cherry red, Dodger blue, slate blue, unbleached linen, and—my favorite—a bright yellow that fades to a dusty straw color over time. Most are too thick to tuck in comfortably, but they make excellent light outer layers, thrown over a turtleneck or T-shirt when temperatures drop. With a weight that feels more substantial than flannel but less structured than a jacket, a chamois shirt is easy to wear without feeling overdone.

Just as I appreciate chamois in winter, I turn to chambray in summer. The key to dressing for the heat is understanding that weight and weave are more important than fiber. People often assume that a cotton or linen suit is the best choice when temperatures exceed 85 degrees. In reality, an 8oz tropical wool will allow body heat to escape and every cooling breeze to pass through, whereas a 14oz cotton twill will cling like a stubborn summer haze, trapping heat like a car left in the midday sun.

Chambray is well-suited for summer because it’s typically lighter and more breathable than oxford cloth or denim. A simple test is to hold the fabric up to the light: the more light that pours through, the more breathable the fabric. The French micro-mill Simonnot Godard produces a dressy chambray suitable for dress shirts. Slightly heavier and more mottled variations of chambray have a distinct workwear sensibility, particularly when finished with details like double-needle stitching, cat-eye buttons, and dual chest pockets. Farmers, sailors, and factory workers wore chambray shirts throughout the 20th century because the fabric was comfortable, inexpensive, and easy to clean. In blue, it also had the added benefit of hiding dirt better than white cotton. As a practical matter, I find chambray to be a workhorse fabric—perfect for summer, lightweight but sturdy, and easy to wear.

Options: For chamois, check Wythe, LL Bean (vintage is even better), RRL (this is very tempting), Alex Mill, and J. Crew. For chambray, check Engineered Garments, Bryceland’s, Big John, Big Yank, Buzz Rickson, Chimala, RRL, Polo Ralph Lauren, Orslow, Imogene + Willie, Todd Snyder, Buck Mason, Bronson, and J. Crew. And yes, Proper Cloth can also do these custom.

The T-Shirt

In an era when gender is one of the most contentious political issues, it’s ironic that nearly everyone wears a garment with roots in womenswear. The humble T-shirt—soft, stretchy, and overflowing from American dresser drawers—began as the top half of the union suit, a garment originally designed in the mid-19th century as a practical alternative to the corsets and petticoats that cinched and stifled. Promoted as “liberty suits” by dress reformers, union suits offered greater mobility and comfort, making them especially popular among suffragists and working-class women. Today, most people remember the union suit as that cartoonish, fire-engine red one-piece underwear, complete with a comically ill-timed back flap—a quirk of practicality turned punchline. Yet, hidden beneath its slapstick associations is the surprising fact that this once-radical garment laid the foundation for what would become the most democratic piece of clothing in the world: the T-shirt.

Like a river carving its path, the union suit flowed from women’s wardrobes into men’s, settling comfortably into the daily grind of farmers, railroad workers, and laborers who prized its warmth and full-body coverage. But in warmer climates, or during sweltering summer months, a full-length under-layer proved excessive. To accommodate changing needs, manufacturers began producing a short-sleeved, cropped version, essentially splitting the original design in half. The top portion, now a lightweight pullover, retained the practicality of the union suit without undue warmth.

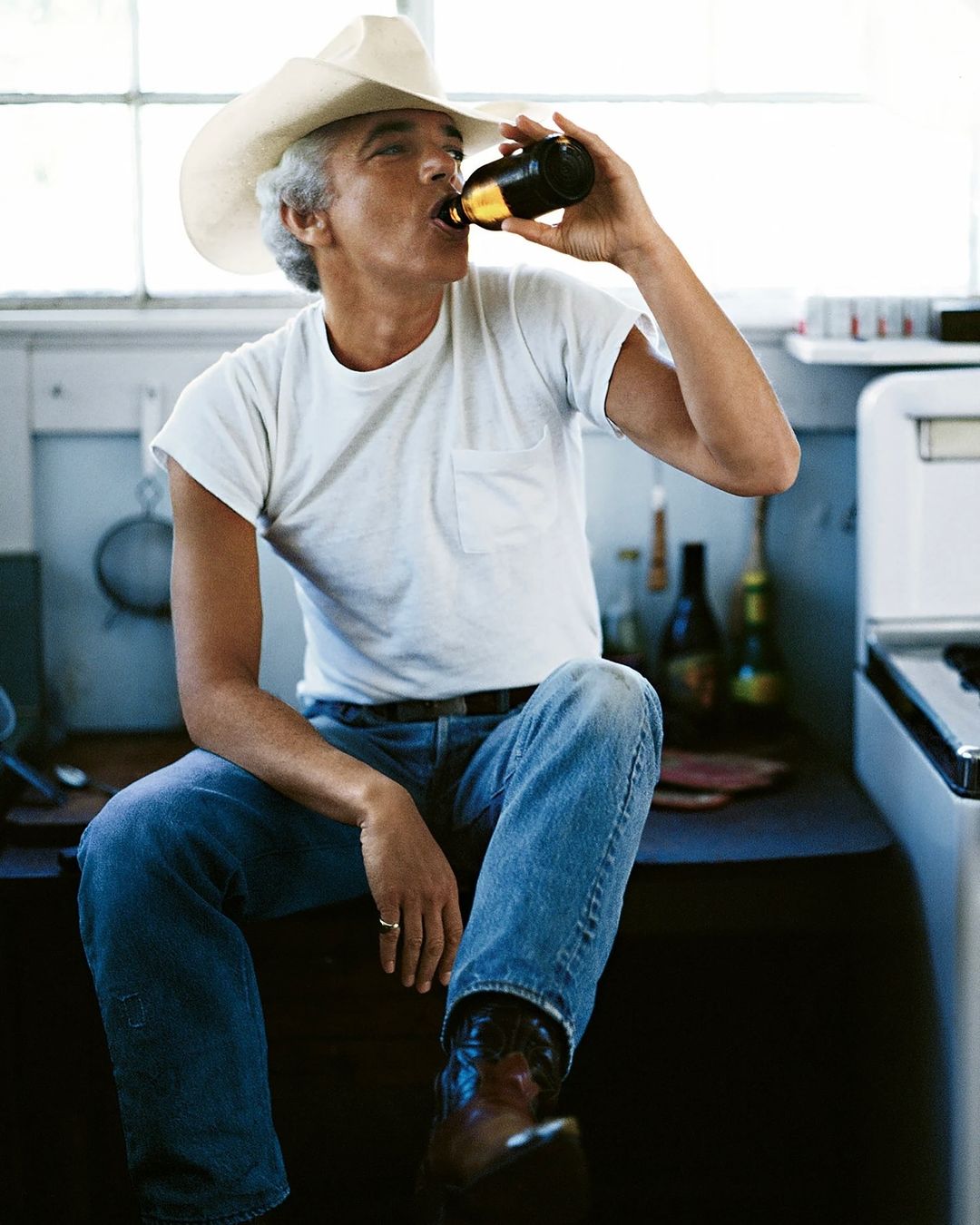

By the early 20th century, this new iteration—often called a “buttonless undershirt”—was being sold as a standalone garment, occasionally pitched as the perfect pullover for bachelors who lacked a helping hand to mend their buttons. In the 1930s, brands like Hanes and Sears began selling it as more than just an unseen base layer, nudging it toward casual wear. The big shift, however, came during World War II, when American soldiers stationed in the Pacific stripped down to their lightweight cotton tees, finding them far more practical in the heat than a full uniform. When these veterans returned home, so did the habit. By the 1950s, Hollywood sealed the deal—Marlon Brando brooded in A Streetcar Named Desire, James Dean smoldered in Rebel Without a Cause, and suddenly, the humble tee wasn’t just an sweat barrier but a symbol of masculine defiance.

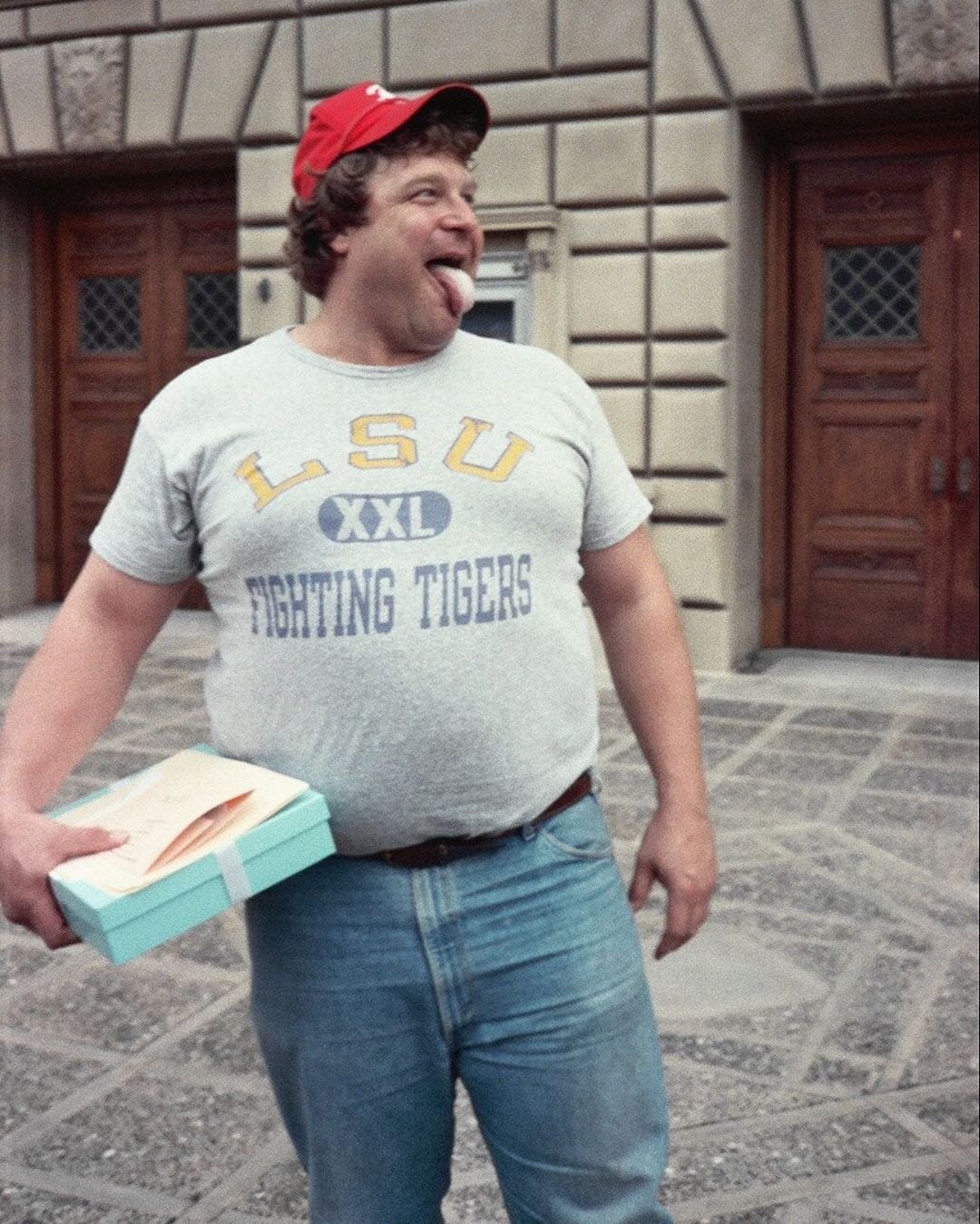

Within a few generations, what began as a radical rejection of corsets evolved into the most worn garment in the world, seen on the backs of dockworkers and drifters, rock stars and retirees, revolutionaries and regular dads. Today, the T-shirt is a blank slate—sometimes quite literally. It can be a walking manifesto, a faded concert relic, or just a comfy, stretchy garment that doesn’t demand ironing. For all its ubiquity, few realize that this wardrobe basic began with women loosening the seams of tradition.

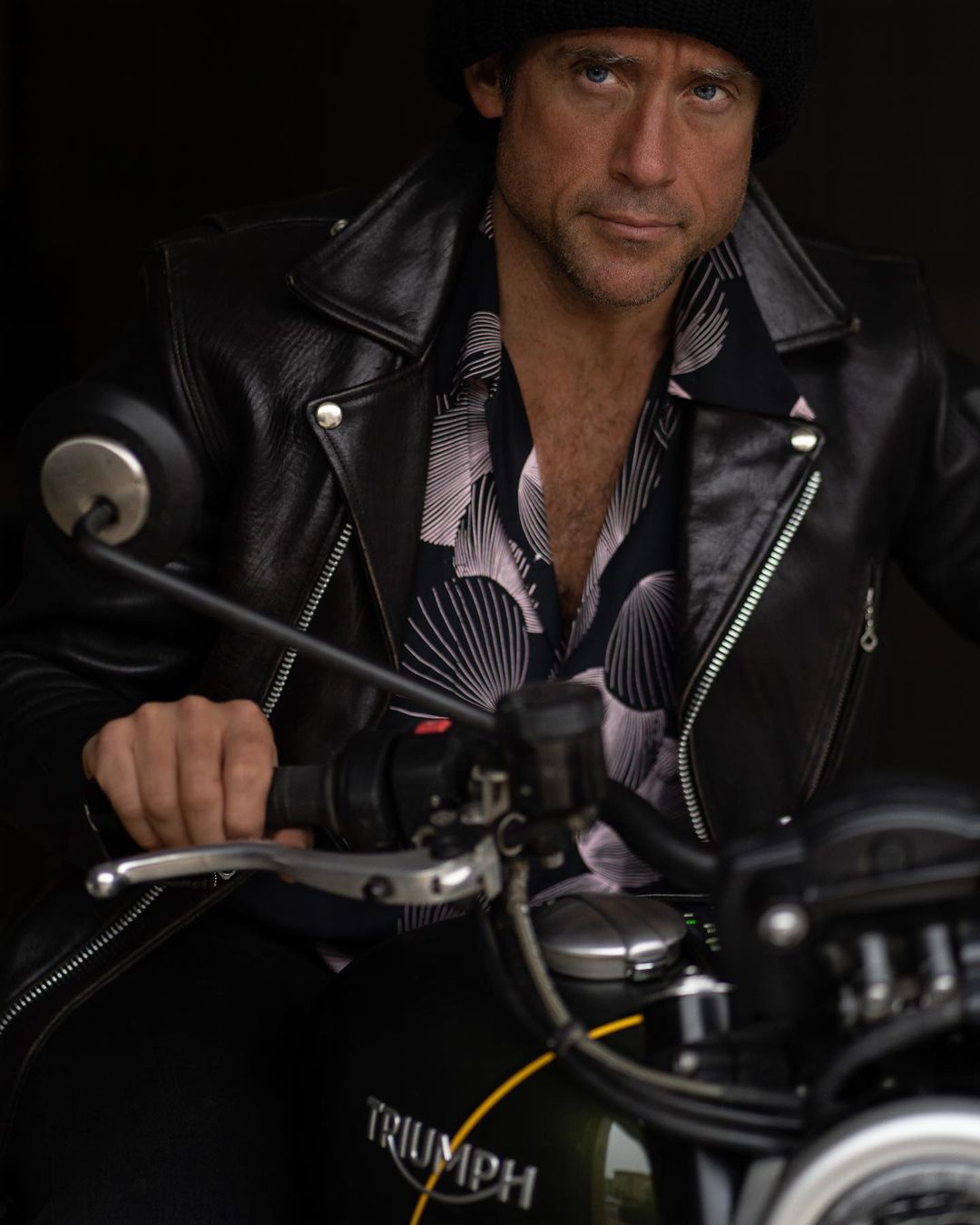

For me, no casual shirt guide is complete without a discussion of t-shirts. They go with denim trucker jackets, black leather double-riders, beaten chore coats, OG-107 field jackets, and anything with a bit of grit. Some can even be teamed with casual tailoring, such as suits and sport coats rendered from cotton, linen, and gabardine. Few people look great in just a t-shirt, but they’re a useful layering piece when teamed with outerwear or even a lightweight camp collar shirt worn open. They’re comfortable on hot days, easy to maintain, and in the case of graphic versions, offer the same visual interest as checks or stripes, albeit in more expressive form.

If you get a graphic tee, remember that sincerity is good and irony is bad. Expensive, status-signaling tees turn what should be effortless into something contrived. At the same time, don’t forget the power of a good cut. Some t-shirts are made with boxy, cropped silhouettes, dropped shoulder seams, and double-fabric constructions that make them drape uniquely. Ultimately, a good t-shirt is whatever allows you to quickly get dressed in the morning while feeling good about yourself—not unlike those Victorian suffragists who first championed stretchy garments.

Options: Hanes Beefy T, Uniqlo, Lady White Co., Imogene + Willie (I prefer the midweight versions), Merz b. Schwanen, Whitesville (famously on The Bear), Velva Sheen, 3sixteen, Buck Mason, Kaptain Sunshine, Unbleached Apparel, Levi’s Vintage Clothing, American Giant, Bronson, and Heddels (made in USA at a union shop).