I was having dinner with a friend a few weeks ago, who happens to be a reader, and he suggested that I post clippings here whenever I write for other outlets. For those who may not know, my social media accounts have somewhat blown-up in the last few years, growing from about 50,000 followers to over two million across three platforms. As such, I’ve been fortunate enough to have editors reach out to me, creating a steady stream of freelancing work.

The downside is that I don’t get to post as much as I would like here. I have a ton of story ideas, such as the social histories of early 20th-century horticulturalist rebels, 1970s Colorado ski instructors, and mid-century British fishermen — all dealing with how these people dressed (which, I’d like to think, has become my “groove;” shedding light on the social histories behind our clothes). But like everyone, I’m also constantly buried in work, and so some of these stories end up getting pushed back in the queue.

The solution, my friend suggested, is that I post little clippings here whenever I write for outlets, which will keep readers engaged and promote my stories. I loathe self-promotion, but the idea seemed good to me, as some people here might like this sort of thing. The series will be called “Cuttings” for whenever I cut excerpts of my writing elsewhere.

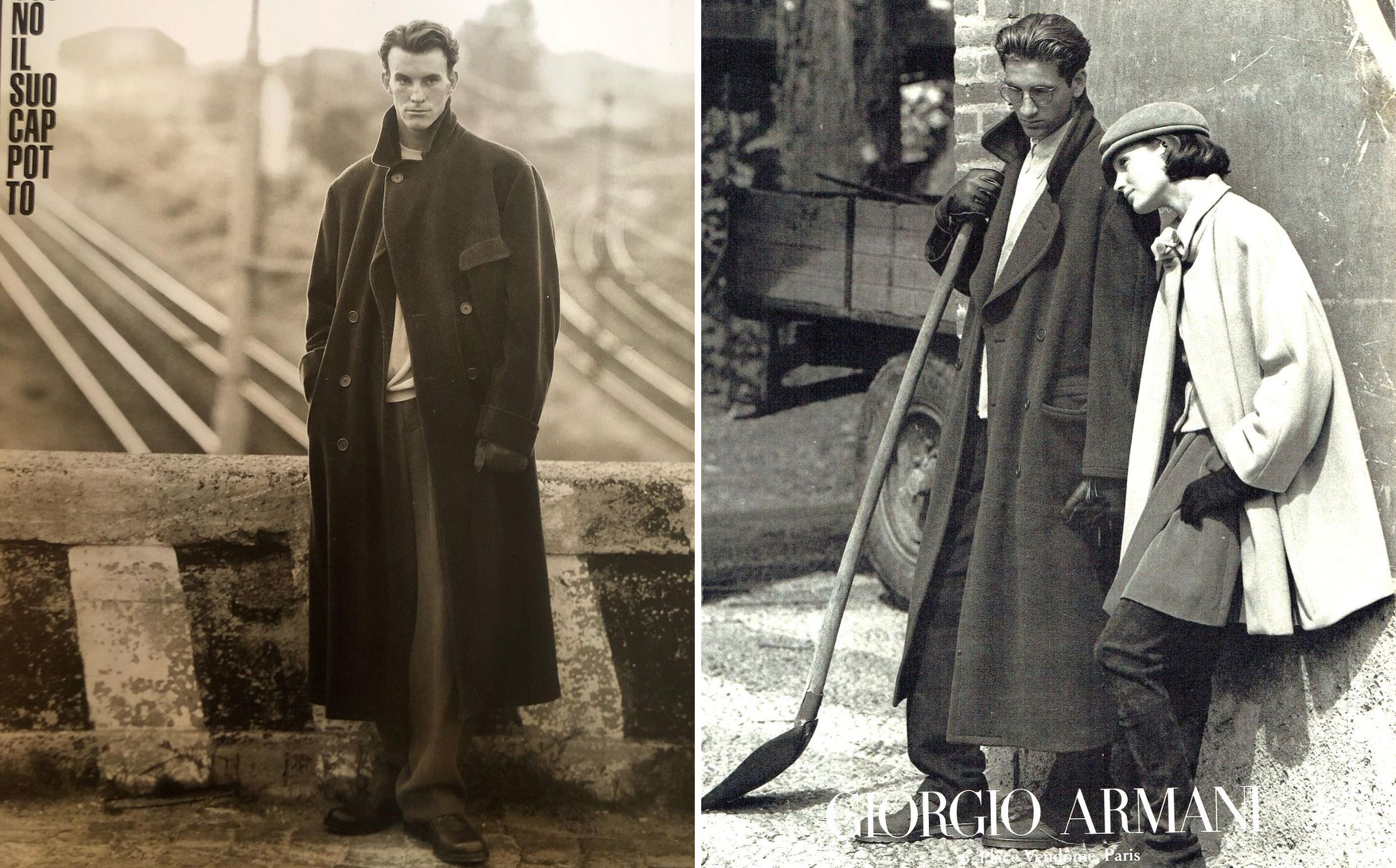

The first story is a reflection on Giorgio Armani, who recently passed away. I remember writing something about him here in 2014, noting that what people often dismissed as oversized, baggy silhouettes were actually quite romantic. I certainly wasn’t the first person to make this observation. My view had been heavily shaped by StyleForum threads, such as the ones dedicated to Yohji Yamamoto and Armani himself.

But Armani was more than just a guy who made oversized clothes, tremendous they may be. He reshaped the industry by forging an alliance between fashion and Hollywood, creating one of the most potent spells that changed how people dream. From my GQ article:

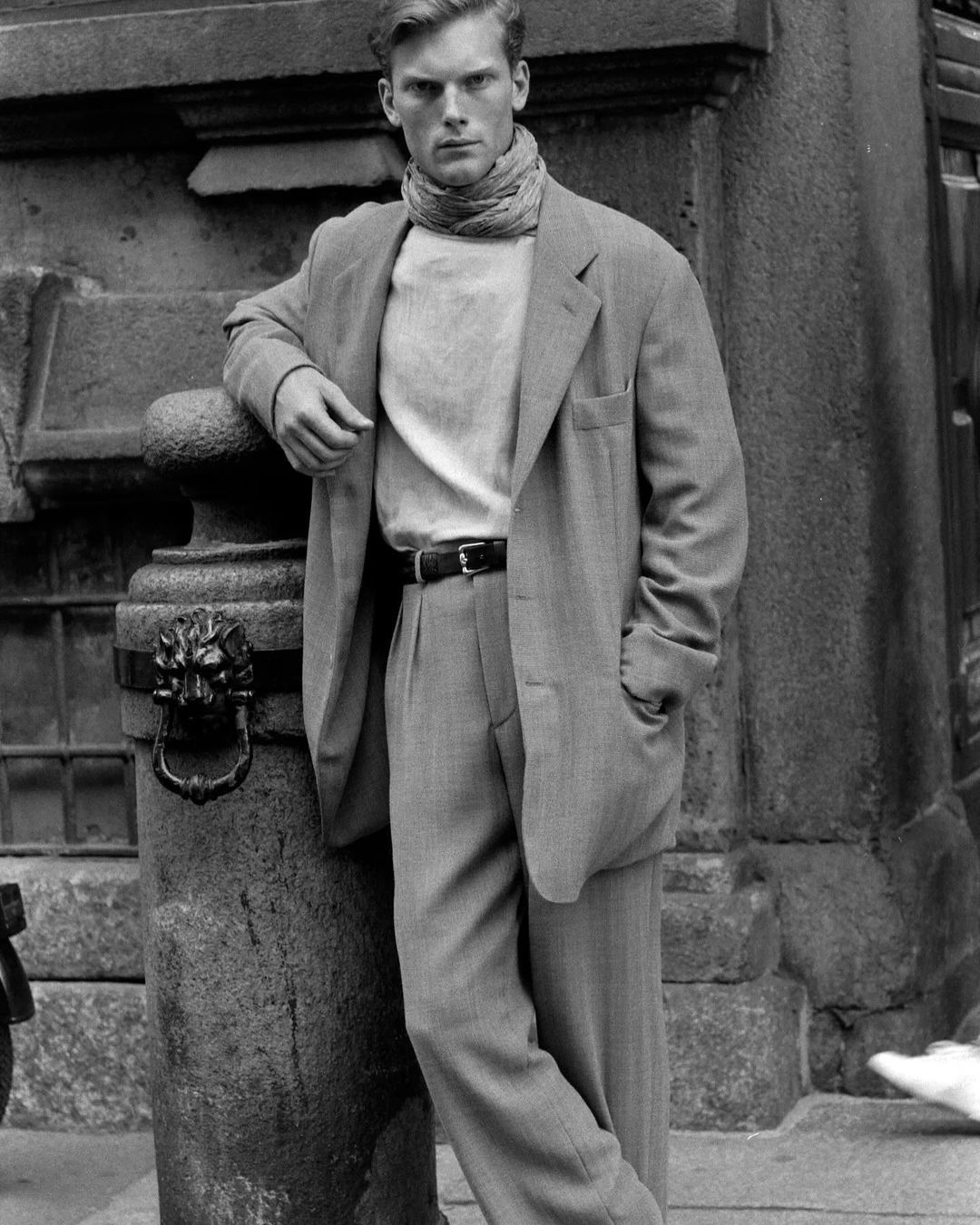

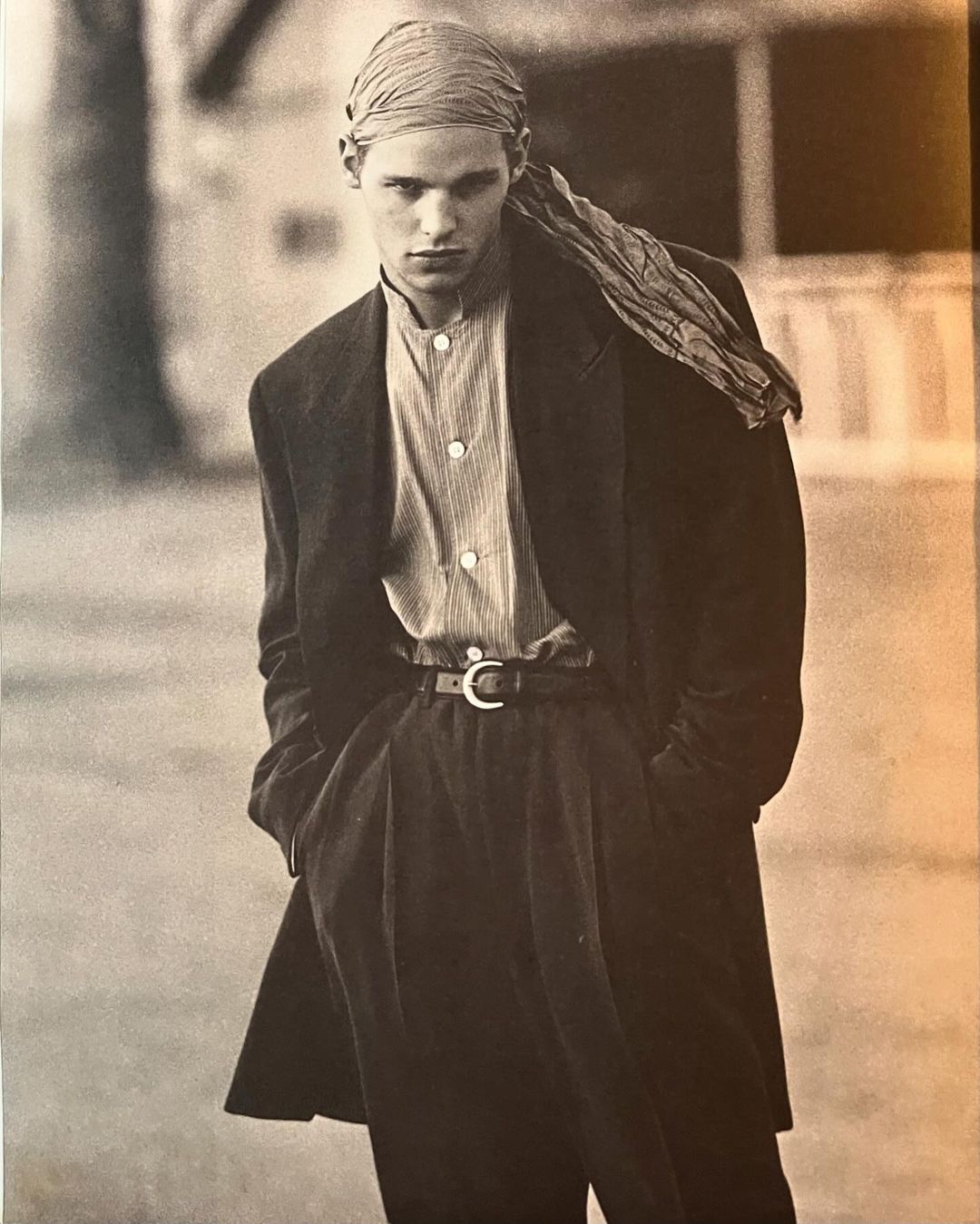

More powerfully, Armani understood that people bought clothes more for what they thought they represented, not just how they were made. His collaboration with Italian photographer Aldo Fallai produced some of the most iconic campaigns of the era: sepia-toned photos of square-shouldered men with swept back hair, wearing slouchy, sumptuous clothes in cobblestone settings that, in Armani’s words, read “like a scene of the best life possible.”

More powerfully, Armani understood that people bought clothes more for what they thought they represented, not just how they were made. His collaboration with Italian photographer Aldo Fallai produced some of the most iconic campaigns of the era: sepia-toned photos of square-shouldered men with swept back hair, wearing slouchy, sumptuous clothes in cobblestone settings that, in Armani’s words, read “like a scene of the best life possible.”

One of Armani’s greatest innovations is that he took this idea and industrialized it, turning it into a profitable PR machine. He dressed Richard Gere for American Gigolo (1980), Kevin Costner in The Bodyguard (1992), and Christian Bale in The Dark Knight (2008); Robert De Niro, Denzel Washington, and Tom Cruise regularly wore his clothes at film premieres and award shows, which allowed Armani to churn out a steady stream of press releases to eager journalists covering the red carpet. When Michael Jackson approached Armani to design a look for his Dangerous tour, Armani reportedly turned him down once he found out that he wouldn’t be in total charge of the wardrobe. For Armani, these projects were less about dressing stars than staging a fantasy that he alone directed.

I also recently wrote something for The Nation about how Republican style has changed over the years. When I was growing up, Republican style was decidedly Brooks Brothers, which is to say navy blazers, oxford cloth button-down shirts, and matte silk, rep striped ties. This style, now known broadly as “Ivy Style,” was shaped by Jewish tailors and their White Anglo-Saxon Protestant customers over the course of the 20th century. It was “Good Taste” in the sense that Pierre Bourdieu once wrote about.

Today, Republican style isn’t so much about a coherent look as it is a cultural garage sale. There’s Trump, whose showboating style is anchored in the “power look” of the 1980s. Where Old Money aesthetics are about playing down wealth, Trump’s padded suits and balloon colored satin ties are about reminding you he’s rich, much like his interior design. And, of course, people who have been central to putting Trump in power, such as Joe Rogan in his henleys and Steve Bannon in his layered black shirts. This aesthetic shift has allowed the GOP to rebrand itself from country club elites to Washington outsiders, even as they continue to pursue tax cuts for the rich, slashing social services, and rolling back business regulations. From my Nation article:

Four decades later, that uniform has all but vanished. The shift isn’t unique to Republicans—men’s fashion writ large has grown increasingly informal. But within the GOP, that broader trend reflects a reordering of power. The Republican Party is no longer governed by Reagan’s acolytes but by Donald Trump, a real estate showman whose understanding of politics is indistinguishable from his understanding of branding. Trump has remade the party not only in spirit, but also—perhaps primarily—in aesthetics, transforming it into a right-wing populist platform in which grievance is currency and performance is power. Where Reaganism once whispered the genteel respectability of brass buttons, Trumpism bellows in red MAGA hats, “Never Surrender” T-shirts, and metallic gold sneakers that give off a tinsel gleam like a casino chandelier. The shift in aesthetics mirrors that in politics: Everything is spectacle, and the louder the spectacle, the more authentic the power it claims to represent.

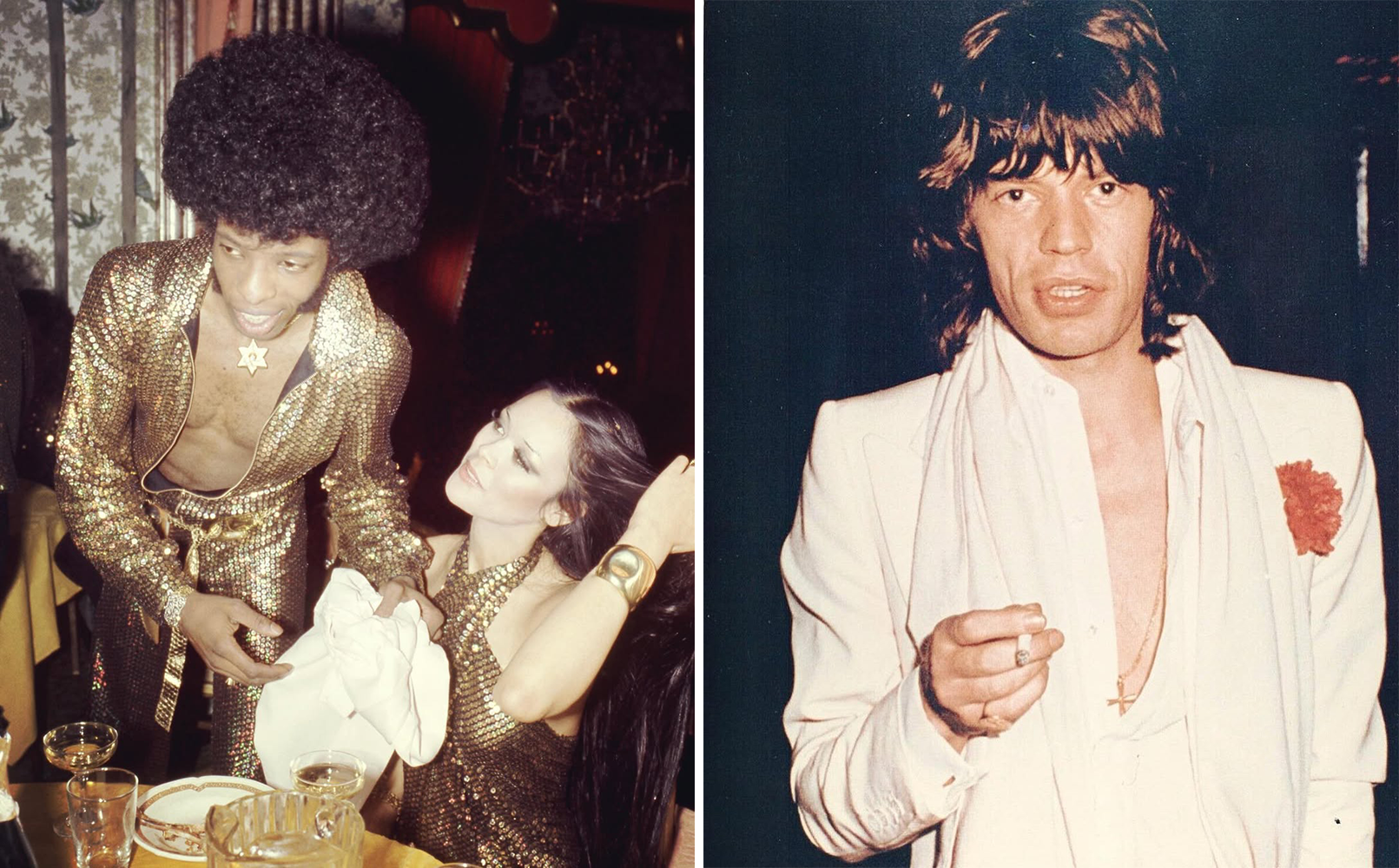

Finally, it’s a little late for this, as we’re entering fall, but The Times asked me to write something about the emergent trend of men unbuttoning their shirts — not just one or two buttons, but sometimes down to their navel. I am, as ever, pro-anything, so long as you understand the cultural language of what you’re doing. The great male renunciation — not just of color, but now apparently of clothes — should be understood in a long lineage of men shedding their layers, first losing the waistcoat, then the tie, then the jacket, and now seemingly the dress shirt. Pulling this off successfully requires some cultural awareness of the 1970s and perhaps some shaggy hair. An excerpt from my Times article:

As cultural codes loosened, the stiff, armoured layers of Victorian respectability eventually fell, one by one. The first casualty was the waistcoat. By the interwar years men had embraced the two-piece suit, revealing the once-invisible shirt beneath. Soon garments once confined to the realm of underthings began migrating outward. Chief among them was the T-shirt, a humble descendant of the calico undervest worn by labourers. Initially meant to warm the torso and absorb sweat, the garment slipped into public view aboard US naval decks, thanks to conscripted sailors, before landing in cinema. There it became the calling card of the disaffected youth: Marlon Brando brooding in A Streetcar Named Desire; James Dean adrift in Rebel Without a Cause.

This current wave of male exhibitionism fits within a longer history of changing dress norms, but it doesn’t emerge directly from such distant pasts. Instead, it’s the product of cultural shifts that have brought sexual display to the forefront of menswear. For much of the past 20 years, men’s fashion has favoured restraint, often drawing on the cultivated taste of old-money elites or the heroic look of mid-century labourers. But with changing taste and shifting cultural norms, designers and style-conscious consumers have begun taking inspiration from the lush decades of the 1970s and 1980s. Consequently menswear has become increasingly louche and libidinal.

Many thanks to everyone for following this blog over the years. I’ve been genuinely surprised by what it has grown into. I promise to post something soon about what I’m excited to wear for fall. I also want to post this story about British versus American fishermen, as I interviewed David Coggins about this years ago and he gave me some great information. More about inspiring fall style to come.