I believe it was in an old blog post on A Suitable Wardrobe where I came across a Bruce Boyer quote—and I paraphrase—that a well-curated wardrobe is the best incentive to stay in shape. By “stay in shape,” he meant staying the same size, of course. If you’ve invested a considerable amount into clothes that hang without a pull or a ripple, you probably don’t want to gain or lose too much weight, either way.

That quote recently came to mind as I started rebuilding my shirt wardrobe. I had a moment of realization last year, much like when Daisy buried her face into Gatsby’s collection of sheer linen and fine flannel shirts, sobbing, “They’re such beautiful shirts.” Except, mine weren’t so beautiful—they were so slim. Things I bought fifteen years ago no longer fit, as I’ve gone up a size. Unlike tailored jackets, button-ups don’t come with inlays, so I’ve been slowly rebuilding my shirt collection, piece by piece.

This process has made me reflect on what constitutes a genuinely useful shirt wardrobe. The tattersalls I thought would go nicely under rustic tweed jackets—while technically true—barely saw any use over the past fifteen years. The discounted Margiela shirt I bought as an experiment looked more like a bad Kickstarter project than thoughtful avant-garde, as I never really had the right pieces—or personality—to make it work. So here’s what I think should be in a basic shirt wardrobe. Like my “Excited to Wear” posts, this is filled with personal prejudice and bias—it’s simply about what I think should be in my wardrobe. But hopefully, you find this more interesting than generic guides about how every man should dress. This guide will be broken into two parts: shirts for tailoring and shirts for casualwear.

The Oxford Cloth Button-Down

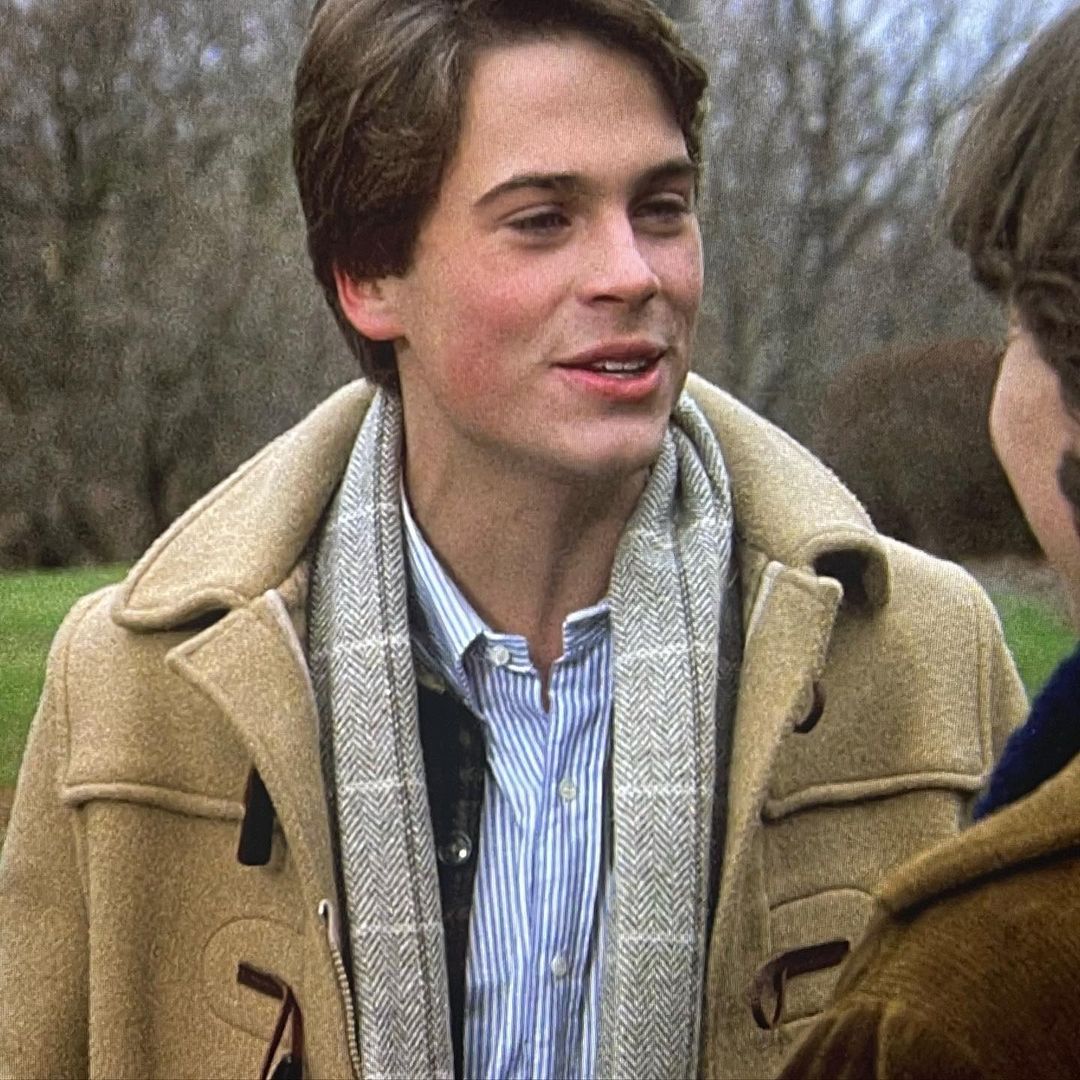

Nearly 20 years after buying my first one, the oxford cloth button-down remains the backbone of my tailored wardrobe. I love it for all the reasons why I love the other hallmarks of classic American style: three-roll-two jackets, polo coats, duffle coats, round-toe Aldens, prickly Shetlands, and turned-up cuffs sitting on top of penny loafers. This casual variant of classic British clothing is more democratic—a reflection of American values—and feels at home in today’s dressed-down world.

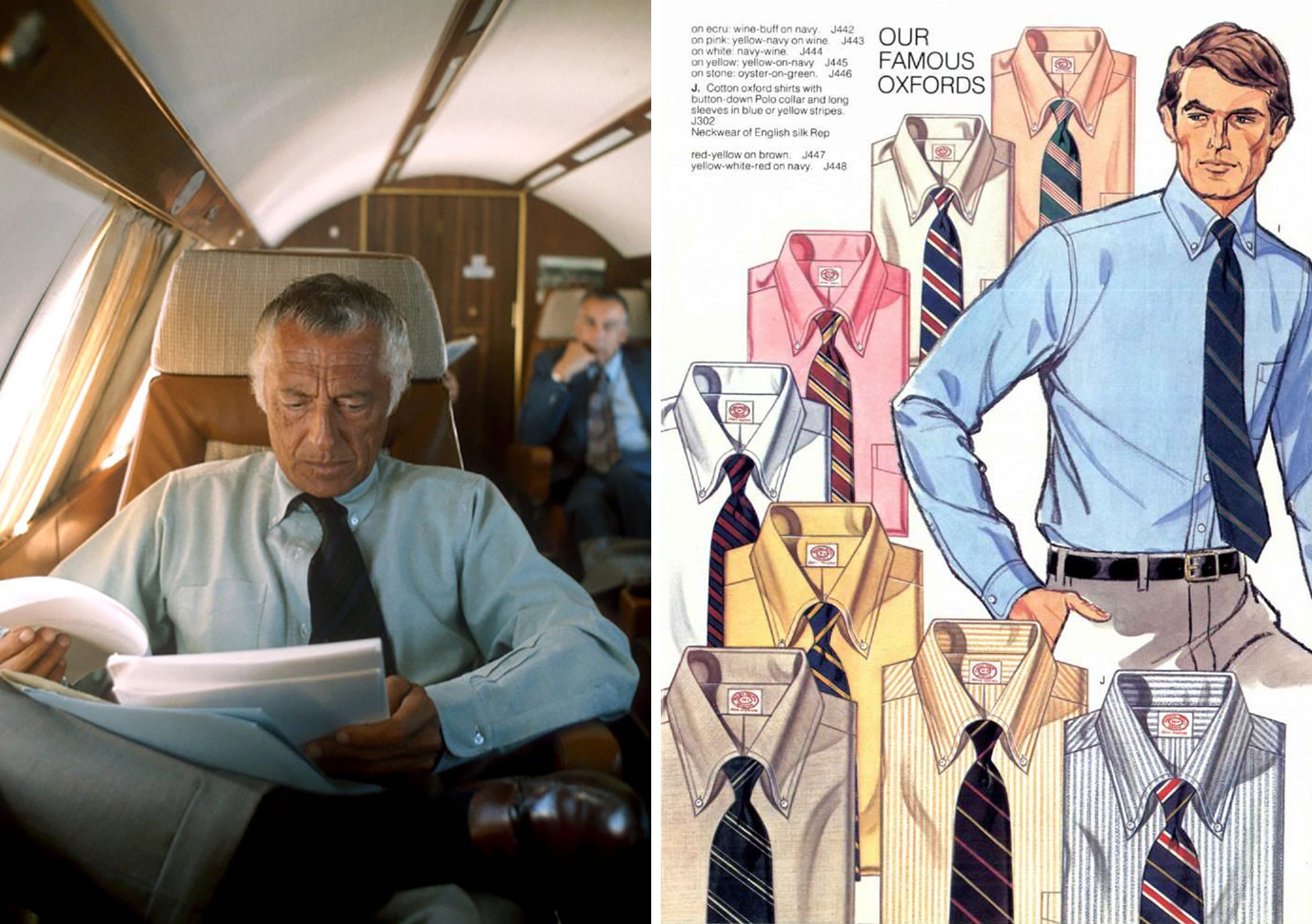

As the story goes, the button-down collar came about in 1896 when John E. Brooks—grandson of Brooks Brothers founder Henry Sands Brooks—noticed English polo players wearing little buttons on their collars to prevent the points from flapping in their faces during play. He thought this invention was charming, so he sent a sample to his tailors with instructions to copy it. In 1900, Brooks Brothers put the new design on their ready-made sport shirts, first marketed as “polo shirts” for their polo-inspired collars. Originally debuted in white cotton cheviots (a stout twill), these shirts were later made in a nubby basketweave known as oxford. Hence the name: oxford cloth button-downs.

Since Brooks Brothers dressed that upwardly mobile class of Americans who saw their fortunes rise with industrial capitalism, their shirts were worn by the kind of people who sent their children to elite preparatory schools that fed into the Ivy League system. That’s how these shirts became part of the language of Ivy Style—worn with soft-shouldered tweeds, rep striped ties, flat-front trousers, and tassel loafers. For much of the 20th century, the button-down epitomized the kind of American featured in Mary McCarthy’s famous short story. It was a symbol of all that is good: casualness, youth, education, trustworthiness, dependability, sport, and professionalism.

For men who measure the distance between the buttons on their two-button Ivy Style jacket cuffs, there are two crucial qualities when shopping for a button-down. First, the collar should be free of the fused interlining typically used to make the collar behave but robs of it of the individual expression, casual ease, and lived-in look that made the mid-century Brooks Brothers shirts charming. Second, the collar points should be long enough to form a gentle curve resembling the outer edges of an ascending angel’s wings. Many collar points today are so diminutive, they look like they’re apologizing for their existence. A good button-down collar should shift and rumple as you move; messiness is part of the charm.

The most useful versions are light blue, as they’re slightly more casual than their bright white counterparts. A light blue button-down can be worn with everything from navy suits to brown tweeds, denim trucker jackets to military field coats, and Shetland knits teamed with five-pocket cords. I recommend getting a stack of light blue button-downs and several in blue-and-white stripes. The striped versions will be helpful when you’re not wearing a tie, as the pattern adds visual interest where a necktie would typically occupy. Since the collar points fasten onto the shirt, they won’t collapse and slip under your lapels, unlike spread collars when unsupported by neckwear.

If you still have room in your wardrobe, a single candy stripe in cheery colors such as lemon yellow, blush pink, or brick red can be nice when it feels monotonous to rotate between the same solid and striped blues. But I’ll be honest: I rarely wore mine, as I found it more useful to switch between different jackets and sometimes ties. That said, I plan to get a single colorful stripe because you never know.

I recommend getting the bulk of your dress shirts from a bespoke shirtmaker, if the option is available. Doing so simplifies the shopping process, allows you to get the best fit, and removes you from the whims of designers who may blow with the wind. I’ve been happily using Ascot Chang for the last fifteen years. Although their shirts lack the fine handwork seen in French or Southern Italian shirtmaking, they are consistent in fit, reliable in service, and have multiple locations in addition to their traveling trunk shows. One of the hidden upsides of using a bespoke shirtmaker is that, once they have your pattern, it’s easy to get anything made, so long as it can be produced on the same machines that sew dress shirts—pajamas, dressing gowns, shirt jackets, and even boxers made from fine shirtings if you need. For that authentic mid-century look, buy an old Brooks Brothers shirt off eBay and give it to your shirtmaker to copy.

Of course, an argument can be made that a shirt is just an object on which more important layers are laid. Perfection in fit, such as matching the shirt’s shoulder slope to your body, is mostly hidden behind a jacket. If you fit well enough in ready-to-wear, you can get much better materials or finer workmanship without spending more money. G. Inglese and 100 Hands’s Gold Line offer some of the finest ready-to-wear dress shirts I’ve seen, as they have a gratuitous level of handwork that would cost a fortune in bespoke. Brooks Brothers, Kamakura, and Drake’s are also great for ready-made button-downs. Proper Cloth is a nice compromise between these two worlds. Their online made-to-measure service allows you to dial in the fit without paying bespoke prices. Unlike traditional bespoke makers, they have a wider range of casual materials, making them useful for some styles discussed in a later post.

Options: For bespoke, check out Ascot Chang, Budd, Dege & Skinner, Hume, Sean O’Flynn, Marc Lauwers, Simone Abbarchi, Luca Avitabile, CEGO, Anto, and 100 Hands (available at The Armoury and Tailor’s Keep). For online made-to-measure, Proper Cloth is the best company I’ve used of the nine online MTM operations I’ve tried (I like their Soft Ivy button-down). Mercer & Sons is known for their custom button-down shirts, although I find the fit to be very baggy (or charmingly full, depending on your taste). For ready-to-wear, check Brooks Brothers, J. Press, O’Connell’s, Andover Shop, Ben Silver, Drake’s, Besnard, Bryceland’s, The Armoury, Anglo Italian, Jake’s London, The Anthology, Berg & Berg, Kamakura, G. Inglese, and Spier & Mackay.

The One White Shirt

Menswear guides often treat white spread-collar dress shirts as a universal staple, claiming they’re a neutral backdrop that offers versatility and simplicity. But in reality, your need for white dress shirts should align with how often you wear a suit and tie.

White dress shirts, particularly in smooth materials such as poplin, have limited utility because they’re primarily “city shirts.” Historically, men wore these with dark worsted suits, polished black oxfords, and Macclesfield foulard ties in business settings, particularly in London. During the Victorian era, white linen shirts with detachable collars signaled wealth, as they dirtied quickly and required expensive upkeep. This legacy makes white dress shirts one of the more formal options in your wardrobe. They’re far better suited to suits and ties than jeans or sports coats.

That said, just as everyone should own a “sincere suit,” I believe you should have all of the accouterments you need to wear with that garment—dark brown or black dress shoes, a sober-colored tie, and a white dress shirt. For most men, this is still the expected uniform for weddings, funerals, religious services, and court appearances. Opt for a semi-spread collar with collar points long enough to neatly tuck under your jacket’s lapels. This creates a smooth, continuous line under your chin, framing your august visage. I would also opt for slightly dressier details: a French placket, no chest pocket, and mother-of-pearl buttons. Avoid cutaway collars, as they’re aggressive and pair best with Windsor knots, which have a studied symmetry that spoils dégagé sensibility of a good tailored ensemble.

Options: If you want the perfect fit, try one of the bespoke shirtmakers mentioned above. If bespoke shirtmaking is not available to you, but you still want something custom, try Proper Cloth. If you’re shopping for ready-to-wear and want very fine craftsmanship, try G. Inglese or 100 Hands’s Gold Line. If you’re a larger guy and hard to fit, check O’Connell’s. If you’re looking for something affordable, check out Spier & Mackay. Any of the companies mentioned in this post will also have white dress shirts, as they’re such a basic item.

The Not-Quite-White Shirt

In his book The Suit, conservative essayist Michael Anton suggested adding colored shirts to the standard white and light blue wardrobe staples. His top pick was pink, followed by yellow, lavender, and the rare sage green. Much like his recommendations for balmoral boots and BlazerSuits—which I tried and ultimately found to be costly, misguided experiments—the pastel-colored shirts I’ve accumulated over the years have mainly gone unworn. They’ve always felt too dandy, working better as stripes, where white lines mute the candy color.

Instead, I’ve found that ecru fulfills the promise other colors aspire to but rarely deliver. In a world where most men are free from the cavils of propriety, an ecru shirt can be worn with dark worsted business suits, but won’t look incomplete without neckwear. Contrast this with a stark white shirt, which can feel as barren as a night sky without stars when worn tieless. On bright summer days, ecru is gentler on the eyes than optic white. And for those whose taste leans as conservative as mine, ecru adds something unexpected without veering into colors that feel a little too preppy.

The challenge is finding the right material. When the hue has too much grey, it can look dingy; if it’s too yellow, it has a warmth that clashes with the cooler tones in one’s wardrobe. The ideal ecru sits in the middle—a creamy, slightly yellow, off-white that resembles the color of unbleached cotton. This hue can be worn with ties in conservative colors such as navy, dark brown, or black, but also doesn’t look empty without neckwear. It beautifully complements brown houndstooth tweeds and adds something special to navy suits.

Options: G. Inglese, Besnard, Proper Cloth, Drake’s, Far East Manufacturing, Maus & Hoffman, Junior’s, The Anthology, and Spier & Mackay

The Polo

When I was on StyleForum, I sometimes found myself the lone defender of polo shirts, the pique cotton flag of business casual. On the more casual side of the forum, polo shirts were often derided as the unredeemable uniform of preppy villains and golfing uncles, a way for middle-aged men to cling to their dignity, even as various animals—snapping alligators, smiling whales, and galloping horses—adorned their chest like a boutonniere.

I admit it’s hard to defend the basic polo you find littered in every mall. But as I’ve gotten older, I’ve found them to be useful for several reasons. In a dressed-down world, the right polo can knock out some of the formality inherent in tailoring. Since knits are less prone to wrinkling than wovens, they also allow you to look presentable without ironing. On more than a few occasions, I’ve riffled through my dresser drawer, looking for a soft polo shirt when pressed for time. You can wear a polo shirt with almost any tailored jacket—rough tweeds, casual cotton suits, and even chalkstripe flannel double-breateds. It looks as natural with shorts in the summertime as it does with formal tailoring in the winter. If you travel on long flights, a stretchy polo will be more comfortable than any button-up.

The key is to get the right one. I’ve found long-sleeve polo shirts to be more useful than short sleeves, as you can show the requisite quarter-inch of cuff when wearing a tailored jacket. Ones made with a collar band will stand up better than the floppy, unstarched collars typical on Lacoste (again, useful for tailoring). If the polo doesn’t have a collar band, I prefer skipper collars over the traditional two- or three-button placket. If you get the shirt in a finer material than pique cotton, it basically becomes a sweater, successfully shaking off the associations mentioned above. My favorite colors are light blue (functions like a dress shirt), navy (useful for light colored jackets), and surprisingly black (goes well with tailored jackets in brown or grey, making the outfit feel a bit sleeker and more modern without the “divorced man” energy of black dress shirts).

Options: Proper Cloth for made-to-measure polos (I think their Soft Roma cutaway collar works well for polos). For ready-to-wear, try G. Inglese, Besnard, The Armoury, Bryceland’s, Stoffa, Anglo Italian, Todd Snyder, Suit Supply, Grand Le Mar, and Luca Faloni. Todd Snyder polos are kind of pricey, but I’ve been really into their collar designs. Try J. Crew for something similar but more affordable.

The One Piece Collar

A retailer once told me that he mostly considers his necktie inventory part of his store decor, like bars displaying antique liquor ads or currencies from exotic nations now defunct. I still enjoy neckties, but it’s undeniable that the accessory has fallen on hard times. In the last 15 years, neckwear sales have stumbled so far and so quickly that the Suffolk-based silk printer Vanners shuttered after nearly 280 years of operation.

There are better and worse ways to go open-collar. Light blue oxford button-downs look more natural without neckwear than plain white poplin spread collars. Certain styles, such as long-sleeve polo shirts and turtlenecks, don’t demand neckwear at all. I’ve also been enjoying one-piece collars, which are made with a placket that flows seamlessly into the collar points, forming a unique roll that recalls the glory days of 20th-century vacations abroad.

These work surprisingly well even in solid whites, as pictured above, but you can get them in striped shirtings or mid-blue chambrays finished with mother-of-pearl buttons, single-needle stitching, and a pocketless chest (to keep it simple). The style works with casual suits or sport coats, particularly in spring/ summer materials such as linen, cotton, or seersucker. In the early fall days, I even wear mine with tweed.

I occasionally find myself adjusting the collar points, which can be annoying. Since the points don’t fasten onto the body and can be a bit long, sometimes you have to double-check in the mirror to ensure it’s sitting right. It’s not ideal, but it’s still a useful enough style that I plan on getting two in my new shirt wardrobe—one in ecru and another in a blue-and-white stripe.

Options: G. Inglese, The Anthology, Edward Sexton, Kamakura, Suitsupply, Grand Le Mar, and The Gaudry.

The Rest

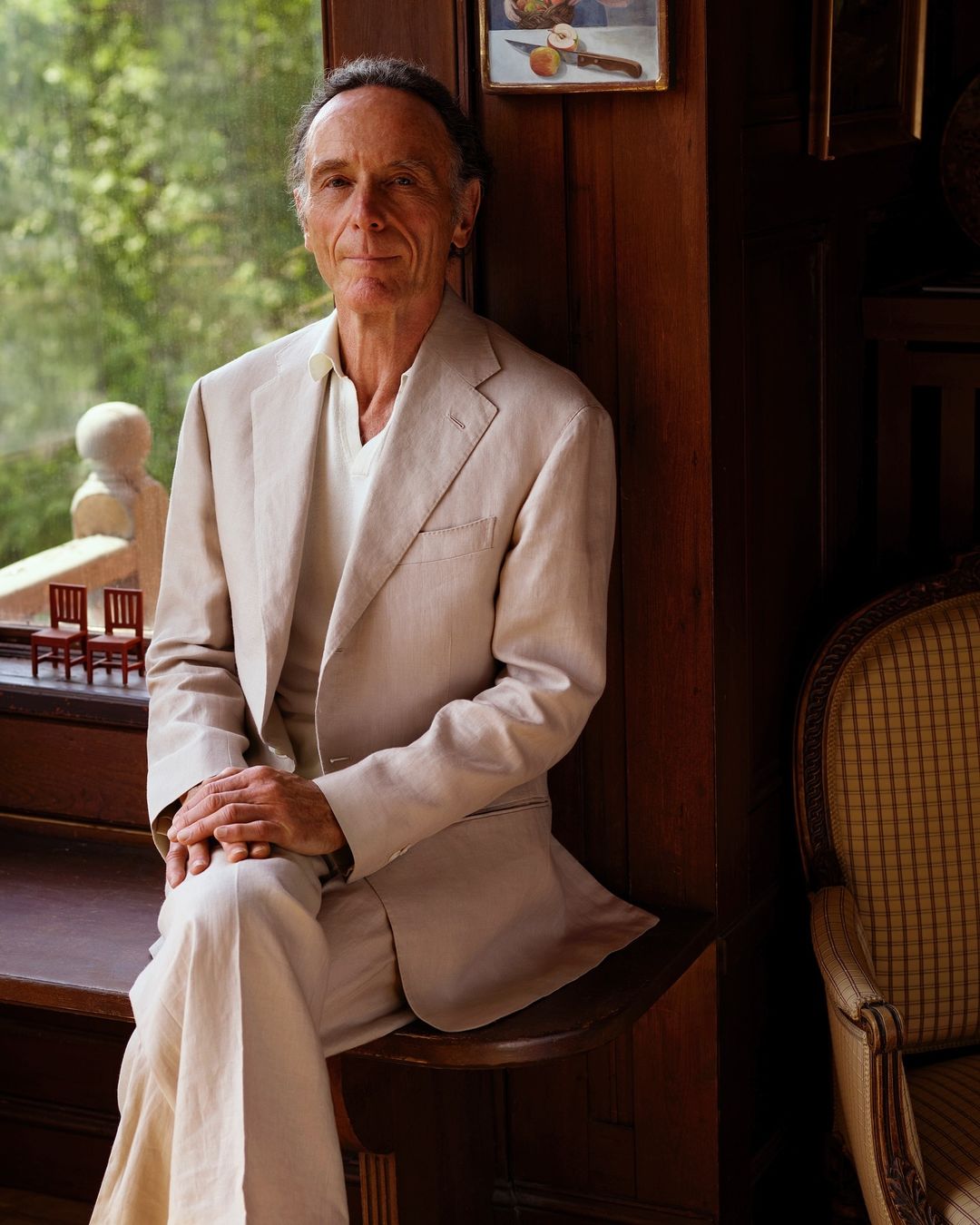

There are a few odds-and-ends worth mentioning. Years ago, I bought some cut lengths of brushed oxfords, which I find goes even better under nubby tweeds than the plain variety. Brushed oxford is precisely what it sounds like—something like the Shaggy Dog version of traditional oxford, which gives it a flannel-like finish. Bespoke shoemaker Nicholas Templeman can be seen wearing one on Instagram.

Last year, at a San Francisco trunk show, I saw James Macauslan, former cutter at Budd and now independent shirtmaker under the banner Hume. He was wearing a light blue voile shirt that was surprisingly opaque. As some readers may know, voile is the tropical wool of shirtings—featherweight and open weave, it’s prized for its breathability on hot, humid days. The problem is that the weave is so open you can look indecent without a jacket, particularly if the fabric is white. But I was surprised by how wearable it was in light blue. James wasn’t wearing a jacket that day, and if he had not told me the fabric was voile, I wouldn’t have known. I’m considering getting one for when temps soar above 90 degrees.

I’ve also found it useful to have various types of stripes—something like an awning stripe, pencil stripe, and reverse stripe. Patterns sit more comfortably alongside each other when they vary in scale, type, and intensity. If you find your banker striped shirts look uncomfortable under a chalk stripe suit, try switching the shirt for a slightly finer or stronger pattern, which helps avoid the Moire effect. Additionally, I’ll always have a special place in my heart for chambray, which is a plain weave fabric typically made with a mix of blue and white yarns, giving a subtle depth in color. The fabric reminds me of a legendary controversy on StyleForum, where one member’s insistence on being right brought down the shirting inventory at no fewer than two online stores. I bought a lifetime supply of Simonnot Godard chambray in the aftermath, but functionally, you can achieve a similar look with end-on-end, another fine plain weave.

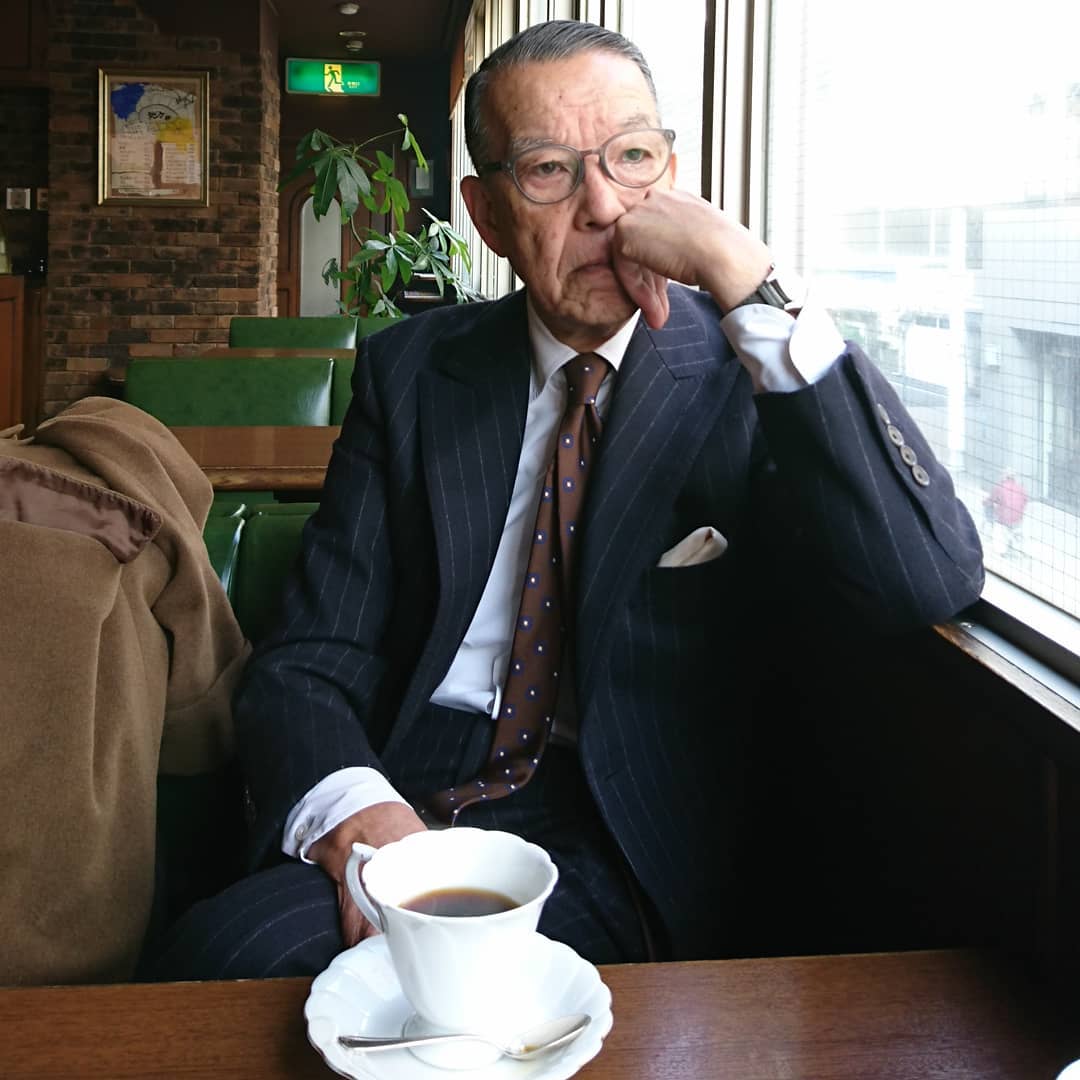

Finally, you may have noticed that this list focuses on basic colors such as white and light blue—and mostly the second. That’s because light blue shirts help dress down tailored jackets. And by simplifying your wardrobe around just two colors, you make it easier to get dressed in the morning. The decision then becomes: “What level of formality do I want to communicate, and do I want to wear a tie?” This simplifies the process of putting together a tailored outfit while still allowing you to create new ensembles by wearing different suits or sport coats. As you browse through photos of well-dressed men in the future, pay attention to how many keep their shirt choices simple.

Options: Similar to white shirts, you can find good options at all the brands, shops, and tailors mentioned above.