In the mid-2000s, I used to take the bus to Kinokuniya, an Asian bookstore in San Francisco that sold Japanese magazines like Men’s Precious, Men’s Ex, and, of course, the famous Free & Easy. Non-English publications, then as now, covered classic menswear better than their English counterparts. While American magazines like GQ and Esquire featured articles on Thom Browne and Tom Ford, Japanese publications discussed the differences between English and Italian tailoring, Alden’s many lasts, and specialty retailers like The Andover Shop. The issue, of course, was that the writing was in Japanese, making it unintelligible to anyone who did not know the language. Aside from English brand names, there were only a few amusing English phrases, such as RUGGED MAN and DAD STYLE (terms for workwear and trad, respectively). Despite my misgivings about spending $25 on a magazine I couldn’t read, no one else did this kind of print coverage. The photos alone were an education.

Last summer, I was delighted to learn that Eisuke Yamashita, a former Men’s Precious editor, now runs his own website, Mon Oncle (French for “my uncle”). His site features profiles on menswear legends such as Luciano Barbera, celebrities such as Juzo Itami, and artisans outside the menswear space, such as woodworker Takafumi Mochizuki. I was also pleased to see a multi-part series on Yukio Akamine, whom I regard as the most stylish man alive. Akamine has a long history in the Japanese menswear scene. He’s introduced generations of Japanese men to classic style and consulted for brands such as United Arrows. Nowadays, he runs a made-to-measure tailoring company called Akamine Royal Line and appears on Japanese shows to discuss menswear.

In his Mon Oncle interviews, Akamine shares some charming observations and advice. He encourages people to wear jackets that are full enough to allow for comfortable layering (“It doesn’t make sense if you can’t wear a sweater underneath your jacket”) and recommends using fountain pens on a regular basis (“Write letters and take notes. Dozens of years later, they will be a memory for the next generation.”). Akamine also emphasizes the importance of good manners (“Don’t arrive at someone’s home empty-handed. Purchase something that you enjoyed eating. Take it out of the bag, hold it with both hands and say, ‘Please enjoy this.’ Or wrap it in a furoshiki.”). Regarding style, he says, “You don’t have to read fashion magazines. Open the window and look outside when you wake up in the morning. A man who can cook rice is a hundred times cooler.”

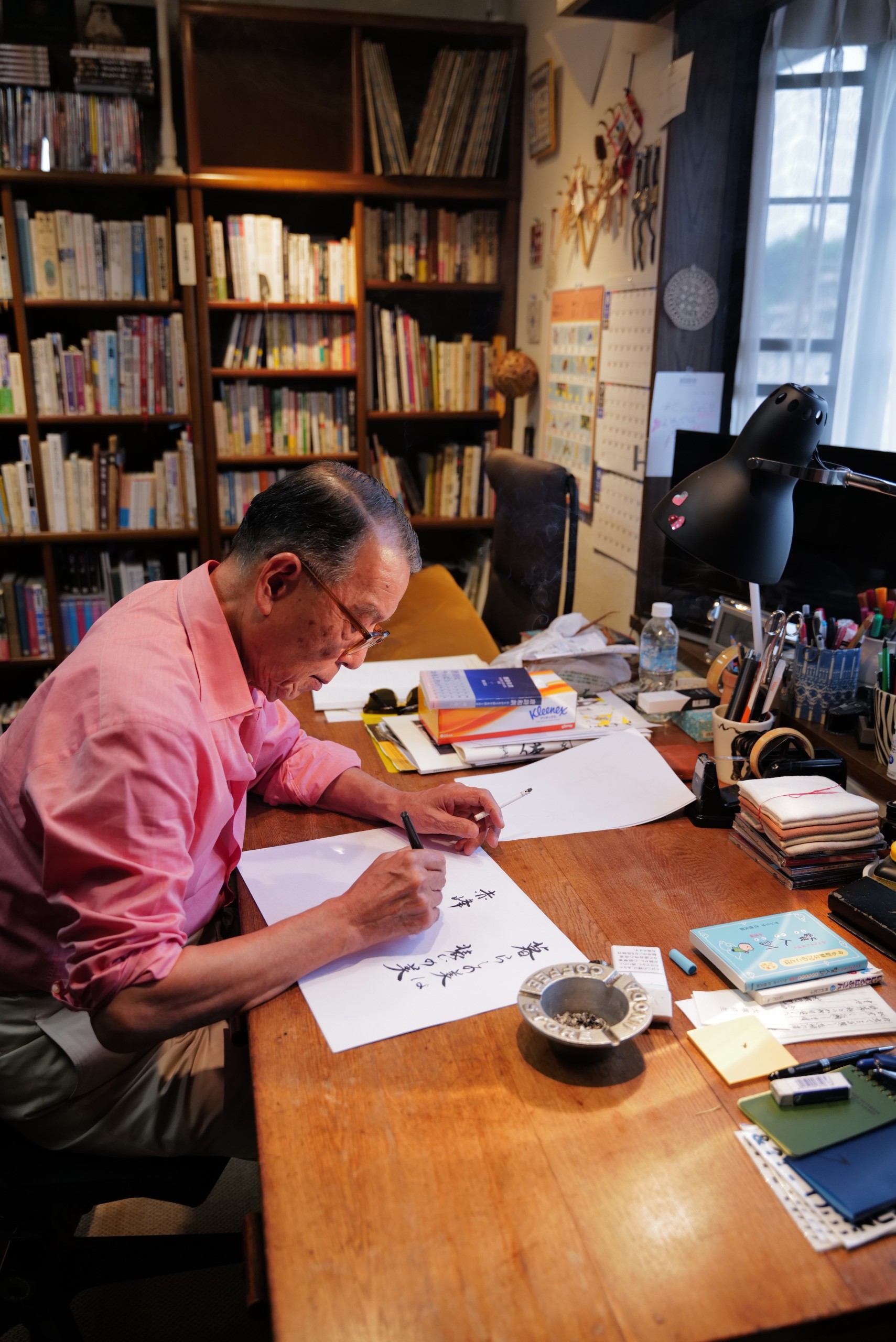

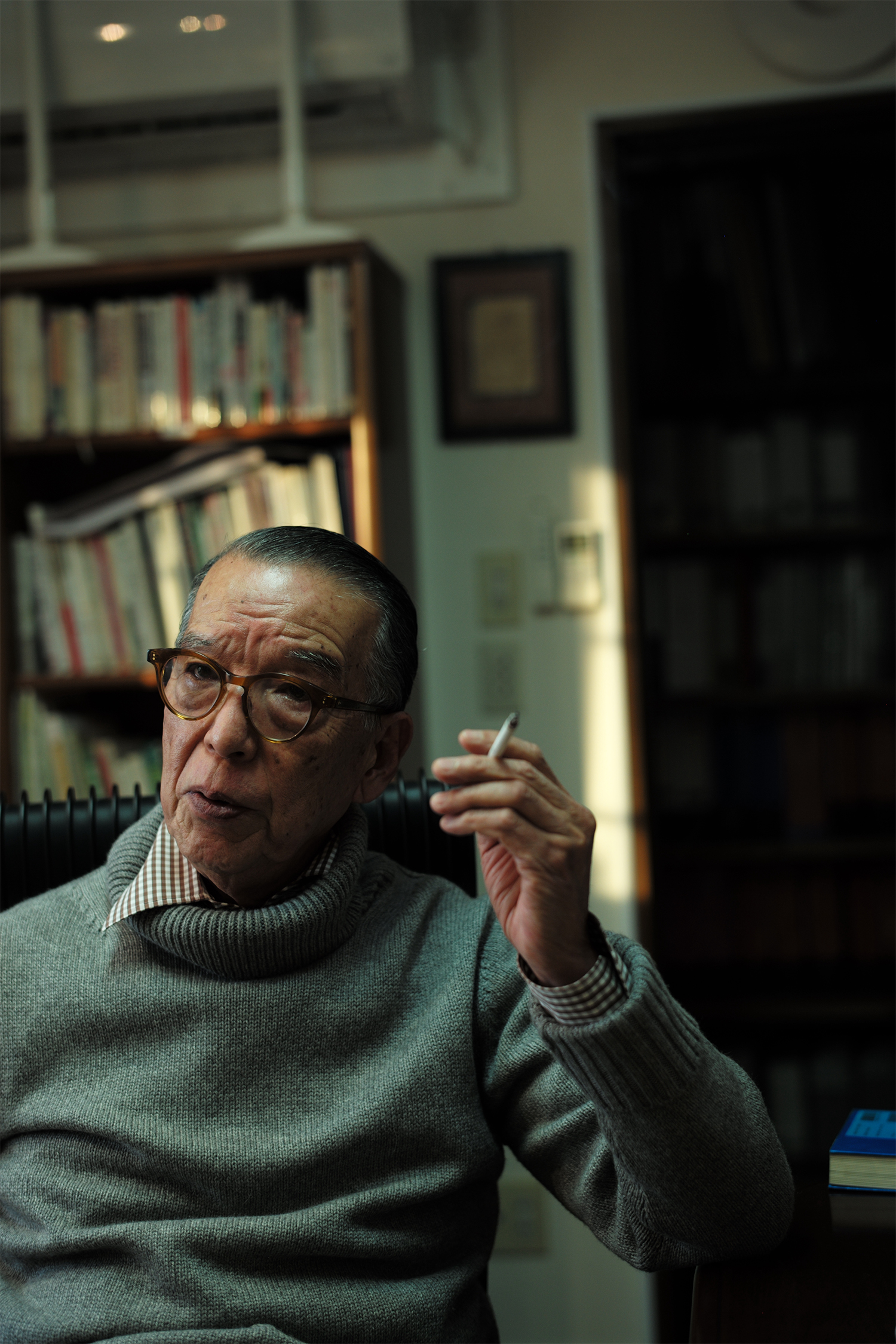

I was so charmed by the interviews that I purchased a copy of Akamine Yukio No Kurashikku (roughly translated to Yukio Akamine, Classic Life), a 280-page, full-color, hardcover book about Akamine’s style and worldview. Yamashita visited Akamine about fifty times during the year-long project, visiting him at his home and accompanying him to his many talks. “This book is more concerned with Mr. Akamine’s philosophy than with fashion,” Yamashita says of the undertaking. “In the book, Mr. Akamime discusses the importance of eating a healthy diet, not putting too much emphasis on efficiency, respecting nature and the artisans who make things, and becoming more interested in films, art, and philosophy. Of course, he also offers some fashion advice, such as why people should avoid fashion trends. But the book’s central message is that to understand the beauty of clothing, you must first recognize the beauty of life.”

Unfortunately, I can’t appreciate the text because I can’t read Japanese. However, after buying a copy for myself, I was so taken with the beautifully photographed images of Akamine that I bought five more copies to give as gifts to friends (the photos in this post were all provided by Yamashita). Yamashita informs me that a few copies are still available. The book costs 10,000 yen (about $74 at today’s exchange rate). Expect to pay slightly more for international shipping if you live outside of Japan (rates are very reasonable). To obtain a copy, send an email to info@mononcle.jp. Like those Japanese menswear magazines, this book will inspire for decades to come.

Having enjoyed the book so much, I recently reached out to Akamine for an interview. Our conversation is below (with translation assistance from Mari Jacobson and editing for brevity by me).

Could you tell us a little about your background? How did you become interested in men’s style? And how did you become involved in the industry?

I was born in Tokyo in 1944. I developed an interest in men’s style when I was 20 years old. At the time, I was traveling through Europe for about two months, visiting England, France, West Germany, Italy, Belgium, and the Netherlands. That period was a very treasured and influential time in my life. Later, I attended Kuwasawa Design School in Tokyo, where I studied Bauhaus design and womenswear, including the works of Dior, Balmain, and Balenciaga. About halfway through my program, I transferred over to menswear. I’ve always been interested in classic style and have been on that path since I started working in apparel.

When I was 28 years old, I started my first company, Way Out But Classic. At the time, Van Jacket was very popular in Japan. They translated American prep and Ivy Style for the Japanese market, and their success altered the course of Japanese fashion. If Van was the Way, I wanted to create something that was Way Out—something adjacent to Ivy, but different. We made things from British fabrics, such as Fox Brothers, and introduced Japanese customers to classics, such as the Baracuta G9. This was my start in the menswear industry.

That’s interesting to hear you were into Ivy, as I know you use Italian tailors nowadays. What drew you to American style? And how has your taste in clothing changed over time?

For tailored clothing, my first inspiration was Brooks Brothers. I traveled to New York City a lot when I was younger, and while there, I often shopped at Brooks Brothers’ flagship on Madison Avenue. I adored their suits and sport coats, particularly the things made by Southwick. Japanese suits were frumpy and old-fashioned back then; their style was unstimulating and stale, and they didn’t appeal to me. Brooks Brothers’ No. 1 Sack Suit, on the other hand, looked stunning and sophisticated. Despite the relatively straight sides, the cut flattered the body and featured clean lines. I became increasingly interested in this style of tailoring.

However, over time, I realized that I was more drawn to the British elements of American style. The United States shares a cultural heritage with Britain, which is evident in its tailoring. So I eventually traveled to England to learn about Savile Row.

There are some significant distinctions between British and American tailoring. Brooks Brothers, for the most part, specializes in a soft shoulder, which means they use minimal shoulder padding, whereas British tailors use thicker shoulder pads and shape their waists with a front dart. I researched the Anglo-Saxon tailoring style as exemplified by Henry Poole, Anderson & Sheppard, and Huntsman. However, because Japanese people have such different body types than most Westerners, determining how these tailoring styles and silhouettes could work for Japanese frames proved difficult.

In the 1980s, people became more interested in Italian tailoring houses like Caraceni and Attolini, which specialize in a softer, more natural silhouette as opposed to the heavier styles from England. Since Italians and Japanese people have similar body types, this was a more relatable direction. I don’t have much interest in Neapolitan style; I was more drawn to Milanese and Florentine tailors, such as my good friend Antonio Liverano. The clothes made by these tailors have a lightness to them. They’re made from robust English fabrics, but have a lightness that makes them well-suited to Italy’s warmer climate. That is the style I’ve become most interested in. Over the years, Liverano has made over forty things for me.

Italian tailors in the south, such as those in Naples and Sicily, do excellent work. But their styling is a little ostentatious and exaggerated—a little too much for me, stylistically. By contrast, the tailors in Milan and Florence produce a more understated style, which makes the clothes easier to wear. My biggest style influences are leading Hollywood men from the 1940s and 1950s, such as Cary Grant and Gregory Peck. The clothes in those classic movies are so elegant, even when compared to Brooks Brothers. All of these influences have shaped my personal sense of style.

Michael Alden of The London Lounge has said he believes some client-tailor relationships result in better work than others—that it’s not just a matter of going into a tailor’s workshop and ordering a suit. As someone who has been on both sides of this equation—a client of bespoke tailors and someone who runs an MTM company—do you believe this is true?

When making a suit for someone, the most important measurement you’ll take is not of their body but of their heart. Of course, a suit needs to properly fit across the shoulders and chest. But before you create the actual suit, the design has to fit into the person’s character, lifestyle, and line of work. Many things can impact this: the wearer’s age, background, where they grew up, and hobbies. So when fitting someone for a suit, I start by chatting with them for at least an hour. What do they like to eat? What types of activities do they enjoy? What type of lifestyle do they live? People from all walks of life order a suit, so it’s important to get a holistic picture of the customer. Knowing more about a person also allows you to recommend the right shirt, tie, socks, and shoes. When done right, a person’s clothing will appear effortless and will reflect their individuality.

You wear clothing in a very elegant way. What do you think it means to dress with elegance?

My personal style is not showy. The intention is not to be on display for others but to embody an internal sense of style. In Japanese culture, there’s the idea of the lunisolar calendar, which breaks up the year into 24 different periods. My clothing choices are informed by the subtle shifts in those seasons. If I am to point to one thing at the core of my style, it’s that I am constantly learning from the colors around me and embodying them with my clothing choices.

I’ve heard about the Japanese lunisolar calendar. Can you explain more?

Seasons are very important to Japanese visual culture and have a very important relationship with color. From the ancient days of the Edo period, there has been a concept of shijyu haccha hyaku nezumi 四十八茶百鼠—48 browns and 100 grays. Enjoying and understanding color is a central component of kimono visual culture. I use these concepts in my own way of dress. Even within my own wardrobe, if we’re talking about the color gray, I have charcoal gray, medium gray, light medium, dark medium—every possible shade of gray. For brown, there is every shade of fallen leaves. When I get dressed in the morning, I choose clothes that will reflect the natural colors that will be around me for that day.

You’ve talked elsewhere about how elegance is more than the clothes you wear. It’s also about behavior and lifestyle. What does this mean to you?

The concept of hayane hayaoki, or “early to bed and early to rise,” is highly valued in Japanese culture. I go to sleep at 10pm and wake up at 4am. It’s also important to have a routine. I always eat breakfast at 7am, lunch at noon, and dinner between 6:30 and 7pm.

Additionally, it’s important to have good manners. In Japanese, there is a term called susosabaki すそさばき which describes the careful and considered way you walk when you wear a kimono. There is a similar term, hashisabaki 箸さばき, where you handle chopsticks with similar grace. Whether you’re using chopsticks or a fork and knife, it’s important to have intention with your movements and maintain good etiquette and posture. In my opinion, having good manners in everyday life is just as important as having an elegant appearance. It’s about living with intention: make your bed, do laundry properly, and iron your clothes. It doesn’t matter if any of these things are going to be seen by anyone; it’s still very important to embody care in the daily motions of your life. Be thoughtful about what food you’re putting into your body. It’s probably the same in the US as in Japan, but the older generation tends to put more care into these types of daily habits, and that’s a big part of why people aren’t as elegant these days.

Perhaps most importantly, I strive to use language in an elegant manner. To treat others with dignity. When discussing the seasons, use poetic language. The importance of word choice in elegant life cannot be overstated.

Japan is similar to the United States in that intergenerational living is becoming increasingly rare; everyone is living so far apart. Parents and grandparents used to teach their children to eat, dress, and make their beds. My parents used to chastise me for using careless language. If I spoke carelessly, I would be told to say it again in a more polite manner. In this way, I learned how to speak properly and how to graciously thank and greet others. It is not only about clothing but also about embodying elegance in your daily habits. It makes no difference how well you dress if you can’t live with elegance.

The cost of quality clothing has skyrocketed in recent years, putting things out of reach for many. In the United States, vintage shops are often a way for people to build quality wardrobes on a budget. Do you shop vintage at all? If so, do you have any tips for vintage shopping?

I love vintage shopping! Since it’s spring right now, if I was looking for a heavier coat, I would look for a Burberry balmacaan. For something lightweight, there are Lee Rider jackets. Those vintage Lee creations will be of superior quality to modern equivalents. I get a lot of pleasure from searching for clothing like this.

If you’re looking for good places to shop, I highly recommend Portobello Market and Camden Market in London. In Japan, there’s David’s Clothing, which specializes in 1930s through 50s made-in-England clothing. If you go to Coenji, there’s WHISTLER Chart clothing, which has a great selection of American shoes, such as vintage Florsheim and Alden. They also carry outerwear from Burberry, Grenfell, and Willis & Geiger, which are popular among young Japanese people today.

The beauty of vintage is that you can get high-quality clothing at an accessible price. If you know what can be altered, you can also take things to the tailor to achieve the perfect fit. For me, it’s less about the number of items in your closet and more about wearing things for a longer period of time. I have clothes in my closet that I’ve been wearing for over 35 years. It takes a bit of knowledge to know what to purchase and how to care for things—this extends from clothing to furniture. However, if you learn that skill, you can build a quality wardrobe on any budget by slowly acquiring things here and there. When you buy cheap clothes and then discard them, you’re contributing to global waste. Cheap clothes don’t have the same heart; they don’t inspire you to take care of what you own. Instead of constantly cycling through cheap purchases, it’s much more satisfying to buy quality items and use them for a long time.

I wrote a series of posts last year exploring how people can develop good taste in clothes. In the series, I asked friends—such as Bruce Boyer, Mark Cho, and George Wang—for their views on how people can develop good taste. I realize this is the million-dollar question—and an impossibly big subject—but what are your suggestions? When it comes to style, how can someone develop good taste?

First and foremost, I recommend studying older Italian, French, and American films. You can learn so much about style from just watching these classic films. As far as directors go, start with François Truffaut for French films and Roberto Rossellini for Italian films.

How about determining which cuts work best with your physique? It seems this is where many men go wrong—it’s not just about finding clothes that fit, but also understanding which silhouettes flatter your figure. Do you have suggestions for how men can figure this out?

The most important part is to make sure you’re getting a proper fit in the shoulders. The shoulders shouldn’t be overly narrow. Second, is the length. After that, you can adjust much of the rest of the coat. All sorts of people get fitted for suits—people with smaller or larger frames, people with bellies, and people with larger backsides. When fitting someone in a tailored garment, you have to balance their frame with the clothes. I also think that a relaxed fit is better than a slim fit. People can gain weight, so adding a little allowance can be a good thing.

For trousers, the waist should be properly fitted and positioned before anything else. I like the waistband to sit 1.5 to 2 cm above the belly button. After that, make sure the lines of the seat are correct. If the fit of the seat is off, it’s going to cause discomfort while sitting—you want to have some slack. When looking at the silhouette of the pants from the side, you want to see clean lines. This is easier with dense fabrics, as they drape better. Some Italian fabrics are too soft and won’t make for proper pants.

The proper leg opening is going to vary depending on your waist size. For Japanese people, the sweet spot is between 21 and 22 centimeters. If the leg opening is too slim, it’s no good; if it’s too wide, it may lean too classic. For Japanese frames, I think it’s best to stay within the 21 to 22 cm range.

I’m curious to know some of your favorite things. Let’s start with your wardrobe. Which garments do you reach for the most?

In the summertime, I like to wear a cotton suit using one of our original fabrics. For fall, I prefer cavalry twill suits. In the winter months, I’ll go for a flannel suit using one of our original fabrics. Of course, Fox Brothers and other companies make fantastic flannel, but if I’m after a very particular combination of details for a double-breasted suit or three-piece suit, I will have my own fabric made. In spring, I also like a Tonik mohair with a 47% mohair content. A grey or blue Tonik mohair suit is a wonderful choice for the weather we’ve been having. In terms of footwear, my all-time favorite pair is a custom pair of John Lobbs that I had made fifty years ago.

Are there any tailors or shoemakers who you think are doing exceptional work right now?

As far as tailors, I’m most deeply connected to Anthonio Liverano. For shoemakers, I have always been a fan of John Lobb of London. There are some great new shoemakers in Japan, but I have yet to find anyone who does work that I enjoy as much as Lobb.

Do you wear a watch? If so, what do you wear?

I have an Omega that I inherited from my father. It’s beautifully made, but more importantly, it’s a memorable keepsake. Over the years, it has become my favorite and a constant reminder of my father.

Do you have any favorite films or music albums?

I really enjoy watching films and have quite a few favorites. For Japanese films, I appreciate the work of Akira Kurosawa, Yasujiro Ozu, and Kenji Mizoguchi. For Mizoguchi, Ugetsu Monogatari; for Ozu, Tokyo Story. Kurosawa is, of course, a world-renowned director. I enjoy his films featuring Toshiro Mifune for their depictions of Japanese stories, such as Yojimbo and Red Beard. For Italian films, Roberto Rossellini’s Journey to Italy and Stromboli, among his other work. I’m a big fan of Rossellini. And from the Italian neorealism movement, Frederico Fellini’s 8 ½ and Luchino Visconti’s Death in Venice. For France, Truffaut and Jean Renoir. For works in the English language, the films of Orson Welles, such as Macbeth. I also enjoy the works of Russian director Andrei Tarkovsky, such as his film The Sacrifice. I could go on and on. I’m a big fan of classic cinema.

I also very much enjoy classical music; my favorites are Chopin and Vivaldi. I like opera, such as Andrea Bocelli. For Italian pop music, Gino Paoli, Lucio Battisti, and Ornella Vanoni. If I get started, I can keep going! I really enjoy French music as well.

You’ve been in the menswear industry for a long time. When you look back at your career, is there a particular memory that you cherish?

My mother passed away around 25 years ago. I happened to be in Florence at Pitti Uomo when I got the call from Japan. I rushed back to Japan and went to the Buddhist temple where her body was being kept. Since it was winter, I was wearing a flannel suit. As I paid my final respects, I put my suit jacket on her body to be cremated with her. I still have the pants from the suit, but the suit jacket is with my mother. This is my most cherished memory.

(Many thanks to Yukio Akamine for taking the time to speak with me, Takahiko Enokido for organizing, Mari Jacobson for translating, and Eisuke Yamashita for allowing me to use his photos for this post. If you would like to purchase the new book about Yukio Akamine, you can email info@mononcle.jp. The book costs 10,000 yen, or roughly $74 given the current exchange rate.)