I was having dinner with Nicholas Templeman a few years ago at Besharam, a small Indian restaurant located on the outskirts of San Francisco. Over spicy vegetarian curries and delicate semolina puffs, we discussed how the British shoemaking trade has changed over the years. I told him I’d recently spoken with Daniel Wegan and Emiko Matsuda, two bespoke shoemakers who, like him, left prestigious West End firms to launch their own shoemaking businesses. Wegan and Matsuda’s operations are modest, with no advertising budgets, celebrity endorsements, or visible shopfronts. When I asked how customers typically find them, they said, “Instagram.” “That was a big part of why I left John Lobb when I did,” Templeman told me. “At the time, some independent makers in Japan made good use of social media, but not many people in the UK. Even the big shops were barely visible online. With the rise of social media sites like Instagram, I felt this was a good time to become independent.”

In the last twenty years, the British bespoke trade has changed dramatically along two fronts: skyrocketing rents and the loss of skilled labor have made it more difficult for larger firms to earn profits and maintain quality. Simultaneously, the internet has created a more informed consumer. These customers, who can be described as “shoe mad” enthusiasts, scour blogs and forums for niche details about shoemaking that few people know or care about. Like Athenian philosophers or Tibetan monks, they use the dialectical process to arrive at truths about handwelting and Goodyear welting, Celastic and leather stiffeners, and the specialized construction techniques that go into the uppers and soles of shoes, such as split-and-lift sewing and fiddleback finishings. For men who have succumbed to the allure of craft, celebrity endorsements and shallow, romantic accounts of the bespoke process are not enough. They want to know the intricate, technical details of shoemaking.

These changes have impacted the British bespoke trade in some crucial ways. In the mid-19th century, Punch co-founder Henry Mayhew published a seminal study on London’s laboring classes. He estimated the city had 28,574 shoemakers (or “bootmakers” if you prefer the Queen’s English) in the 1840s, making it the third most popular occupation. By the end of the century, improvements in ready-made footwear dramatically shrank this number to around 3,000, consolidating many workers into a handful of large firms. Among these businesses were gilded names such as John Lobb, Peal & Company, and Henry Maxwell, who built reputations by making shoes for presidents and pioneers, authors and actors, titans of industry, and other members of the ruling class. They also reaped the benefits of a fawning press. After reading enough breathless prose, wealthy men convinced themselves that spending thousands on shoes “would itself be an act of poetry,” as my friend Réginald-Jérôme de Mans put it.

However, as the 20th century marched forward, the number of West End firms dwindled, further consolidating the trade into a few hands. Firms collapsed due to mismanagement or an inability to compete against the rising tide of cheap, sometimes glued, imported footwear. According to Peter Schweiger, Secretary of The West End Master Bootmakers’ Association, the organization had around fifty registered members when it was founded in 1908. When he joined the association in the mid-1970s, the number dwindled to about eight. Today, the tally stands at four: John Lobb, GJ Cleverley, W.S. Foster & Son, and James Taylor and Son.

Along with the diminishing number of firms, there has also been a dimming of quality. I ordered a pair of dark brown bespoke oxfords from GJ Cleverley a few years ago. The ordering process took a Herculean effort, with five trips to San Francisco’s Huntington Hotel, three of which were for fittings (none of the changes I requested at each fitting was made at the subsequent meeting, making me feel like I was wasting my time). On Christmas Eve, when the shoes arrived, my excitement quickly deflated when I opened the box. The uppers were oddly wrinkled, the soles were scuffed, and despite the unusually high number of fittings, I could slide my index finger behind my heel. The shoes also had a “saggy waist,” a term cordwainers use to describe the separation of the sole from the uppers at the shoe’s midsection. I imagine this detail could have provided some ventilation on a hot summer’s day.

In the time since then, I’ve noticed other issues with Cleverley’s shipments, such as exotic wholecuts with flaky skins, alligator loafers with scales that don’t match across the left and right shoe, gaps around the sole and uppers, back seams that angle outward at different degrees, and shoes delivered with stained uppers. Kirby Allison claims that Cleverley intentionally makes shoes that rock back and forth by using a “twisted last,” which I’m sure exists, but I believe the uneven soles are the result of poor craftsmanship. Over the past few years, I’ve also heard horror stories about people’s time spent on the West End and how they were ignored when they voiced concerns. For clients unfortunate enough to receive botched shoes that wouldn’t even pass the quality standards for factory seconds, sometimes there’s no recourse.

As the larger British bespoke trade feels increasingly like a shell of its former self, running on the fumes of laudatory press generated a generation ago, enthusiasts are becoming more interested in smaller makers, which they discover through Instagram. These independent operations are modest in comparison to their larger counterparts. Instead of a storefront in a West End shopping arcade, lastmakers often work out of their home or an artist’s loft. When traveling internationally to meet with clients, they hold trunk shows in standard hotel rooms as opposed to more luxurious suites. On their Instagrams, there are no celebrity faces or polished images; many are simply taking photos of their work with an iPhone. However, what they lack in glamour and prestige, they make up for in quality and service.

Daniel Wegan, a shy Swede who gained self-assurance through clothing, is one of these artisans; he relocated to Northamptonshire in the summer of 2009 to study bespoke shoemaking. At Gaziano & Girling, Wegan learned his craft, starting as a bottom maker who pulled leather over wooden lasts and hand-stitched uppers into leather insoles. As a quick learner, Wegan has seen his career skyrocket over the last fourteen years. He eventually became the head of Gaziano & Girling’s bespoke department, finished second at the World Shoemaking Competition in 2018, and then won it the following year. Many of his shoes, such as the austerity brogues pictured above, could have been lifted from shoemaking books published in the early twentieth century, which Wegan refers to as the trade’s Golden Age. His work exhibits tight execution, as fine lines wind around his shoes’ bell-shaped heels, tight waists, and elegantly shaped toe boxes. He now runs his own operation, which he calls Catella, and describes his typical customer as a “shoe enthusiast.” “These aren’t people who come in off the street and buy something on impulse; they’ve done their research. They also buy shoes as a hobby, not because they need to build a business wardrobe. These people are coming to see a lastmaker, not a brand. They are coming to see me.”

Nicholas Templeman’s clientele is similar. I first contacted him nine years ago, soon after he left his job as a lastmaker at John Lobb. An online friend who has tried every major West End firm and a few outside of England recommended I use Templeman for my first pair of bespoke shoes because he is “attentive to details and will ensure you’re happy.” He was right. After commissioning three pairs of shoes over the course of eight years, with a fourth pair on its way, I can say Templeman is one of the best craftspeople I’ve ever worked with.

Templeman makes his lasts by wielding a sizeable hinged blade known as a lastmaking knife. Such knives are rarely used nowadays, even in larger bespoke houses, because they take up too much space and require too much finesse to operate. There’s also the matter of keeping the blade sharp, which requires a different set of skills. Templeman uses a lastmaking knife because he was taught to do so at John Lobb, where he trained for seven years before striking out on his own. “I enjoy using them, and if I were to stop, it would feel like a bit of history and tradition is being thrown away,” he says. This blade is used to remove large amounts of material from a rough turn, a wooden block shaved down by turning it once on a lathe. Once the rough turn has been knocked down to a manageable size, Templeman refines the shape with a rasp.

This method is unique in that it arrives at a final shape through subtraction rather than addition. At other bespoke companies, a lastmaker may start with a fine turn, which is a rough turn that has been shaved down further on a lathe. Although it’s possible to shave more material from a fine turn, this method often involves augmenting the last by gluing pieces of wet leather or cork to the areas where the client needs additional volume. In this way, a fine turn is analogous to a tailor’s block pattern. If a shoemaker has a signature look—say, a distinctive silhouette—that draws in customers, this method may work better, as the person is always starting with the same shape.

However, I’ve found Templeman’s method allows me to obtain a broader range of shapes. In the last eight years, I’ve ordered a sleek pair of grained split toes; a rounder, more casual pair of split toes inspired by JM Weston’s Hunt Derby; a black pair of horse-front side-zip boots to replace my boots from Margiela; and now a pair of suede tassel loafers that are on their way. (The first three pairs of shoes are pictured above and below.) Each project has required a dramatically different last, which Templeman has always been able to deliver. I have been impressed by his adaptability, attention to detail, and determination to get things right.

Some years ago, a friend received a pair of shoes from Templeman, which he loved and subsequently wore to a trunk show. At their meeting, Templeman noticed a minor flaw with the shoes that he had initially overlooked and asked the client, my friend, if he could send them back for an adjustment. This level of care and integrity is often lacking in larger operations. The onus to spot problems is commonly placed on the customer, who has to figure out if a sport coat has the correct front-back balance or why the sides of his loafers are bowing out. It’s a twisted version of the traditional client-maker relationship, in which you presumably hire an expert for their eyes and skill. With skyrocketing Mayfair rents, one gets the impression that larger bespoke tailoring and shoemaking operations are turning into brands, and they’re more focused on efficiency than the close, honest relationships written about in mid-century articles.

The West End’s Victorian wage structure certainly does not help. Several outworkers told me that after the last is created, it takes them about 30 to 35 hours to make a pair of shoes. However, they are only paid 350 pounds for each pair delivered (at the current exchange rate, this equates to about $434, earning the shoemaker about $12.40 per hour—below California’s minimum wage). To make a living, an outworker must figure out how to deliver three to five pairs per week, which can be accomplished through efficiency or cutting corners. Shortcuts may include incorrectly skiving the leather, resulting in lumpy toe puffs, or lowering the number of stitches on the welt. By spacing the stitches further apart—say, from the standard 1/4″ spacing to 1/2″—a bottom maker may save themselves half the time sewing, but they have to pull on the threads a little tighter to keep the proper tension. In the end, the welt can separate from the uppers after some wear. Shoemakers call the effect “shark’s teeth” for how the shoes end up “grinning” at you with “teeth” (visible threads) dotted around the perimeter. If the final person checking the shoes doesn’t notice (or doesn’t care), and the customer never raises a fuss, then the operation chugs along. Wegan warns that this is “how quality slips.”

Lastmakers who run their own shop, on the other hand, have more control over the process. Everyone I spoke with said they feel added pressure because of their direct relationship with clients. “When you are an independent shoemaker, you are responsible for the shoes you produce,” says Emiko Matsuda, who formerly worked at Foster & Son. “There’s no hiding place nowadays, especially with social media.” People at a larger shop can hide behind a name or avoid the disappointed eyes of dissatisfied customers by staying in the backroom. But this isn’t possible when the shoes bear your name, and you have to interact directly with clients at trunk shows.

Wegan has a more cynical take. As he sees it, the difference between a large and small shop comes down to the intentions and personalities of the people running them. “One of the reasons why someone ends up running a large operation is because they love money, not shoes,” he posits. “After all, there’s no reason for someone passionate about shoemaking to have a business like that today. Someone may have started this business because they enjoy shoes, but they ended up expanding and owning a Mayfair shop because they desired to live a particular lifestyle. When this type of person goes home, they’re not reading shoemaking books or practicing stitching techniques. This is the distinction between a craftsperson and a large Mayfair operation. It’s similar to the difference between someone who builds cars and a car dealership owner.”

I suspect there’s a more practical explanation for why small shops nowadays deliver better work than the large, heritage firms: a shortage of skilled labor. Over the last century, the British crafts trade has shrunk dramatically, each time trying to withstand successive tidal waves of economic crisis. Improvements in ready-to-wear, the importation of low-cost clothing, and the casualization of men’s wardrobes have left craftspeople with fewer customers, not to mention the damage caused by skyrocketing rents and what economists refer to as Baumol’s cost disease. These factors have combined to leave the trade with a much smaller pool of skilled workers than a generation ago. Prominent West End firms are said to deliver up to five hundred pairs of shoes per year; smaller shops are said to deliver ten to fifty pairs per year. Given the scarcity of skilled labor, it’s much easier for a small shop to find the workers they need.

Smaller businesses also have a more consistent level of quality. The quality of any item in bespoke is determined by the people involved. That would be the cutter and tailor in tailoring, and the lastmaker, closer, and bottom maker in shoemaking. There may be large teams of such people at larger operations, so what you see in the wild or on Instagram may differ from what you’ll get as a customer. Perhaps you’ll be assigned to a different cutter, or your shoes will be routed through a different “assembly line” of closers and bottom makers. With smaller operations, you can be more confident that the hands that produced something you saw online or on a friend will be the same hands that will be laid on your order.

The rise of social media has made it easier for shoemakers to strike out on their own and free themselves from the shackles of large operations. As Matsuda observed, there were fewer independent shoemakers even twenty years ago. But the development of online menswear culture risks displacing another critical element of shoemaking: taste. Back when tailored clothing was still part of people’s daily lives, it would have been evident that certain shoes should be worn in specific ways: a black cap-toe oxford complements a navy suit for town dress, just as square-waisted derbies and boots were worn with tweeds in the countryside. Such clothes were also made by craftspeople who hewed close to tradition, using time-tested techniques and incorporating details based on function.

However, a lot of tailored clothing nowadays feels increasingly unmoored. Suits and sport coats are worn in environments where few other people are wearing such things, or they exist in digital spaces such as Instagram, where an object or a detail can be bounded within the four walls of a JPEG. In this way, it’s easy for people to lose sight of the functional conventions that once governed men’s dress. For instance, riding boots are typically made with a straight cut across the heel breast. This detail, known as a jockey heel, is designed so the boots sit securely in the stirrup. But when details no longer serve a purpose, they can become trends on Instagram. Younger customers and shoemakers commonly mix and match trendy details, creating a pricey version of Mr. Potato Head.

Matsuda is unique in that she has spent over twenty years working in the West End. She moved to England in the late 1990s because, as she put it, she has “relatively big feet for a Japanese girl” and had trouble finding shoes that properly fit her. When she first arrived in London, Matsuda enrolled at Cordwainer’s College, where she studied shoemaking. Later, she took an apprenticeship at Foster & Son, where she learned the art of lastmaking from the legendary Terry Moore, who made lasts for Peal. Matusda remembers the first time she saw Moore at his shabby workbench, where he carved lasts with “beautiful, old tools” and drew patterns on “plain brown wrapping paper.” “I thought, ‘This is it; this is the craft I want to learn.’ From that point, I was determined to become a bespoke shoemaker.”

Under Moore’s tutelage, Matsuda learned the technical skills that go into shoemaking and the logic of how certain details contribute to the whole. Here we see the double-edged sword of Instagram’s rise: the fetishization of the smallest details. “There are more independent shoemakers now than when I started,” Matsuda says. “Many of them are very talented. When you look at the shoemakers in Japan, many of them are creating shoes at a quality level we didn’t see twenty years ago.”

“At the same time, this doesn’t mean that younger shoemakers necessarily know traditional West End shoemaking techniques or how classic shoes relate to a gentlemen’s wardrobe,” she continues. “I think some people focus so much on this idea of ‘quality’ that they forget the rules. For example, my teacher Terry Moore taught me that beveled waists don’t belong on casual shoes because casual shoes need to be flexible, and a fiddleback waist prevents that. But some shoemakers now put them on casual shoes because they think it looks nice or they feel it shows off their skill.” When choosing a shoemaker, consider their skill as an artisan and their ability to provide gentle guidance to create a lasting design.

While interviewing craftspeople for this story, I was struck by how small the British bespoke shoe trade looks today. If Henry Mayhew’s study is to be believed, the number of shoemakers in London shrank from nearly 29k in the 1840s to an estimated 3k by the turn of the century. When I asked one shoemaker how many there are today, he guessed, “fewer than a hundred.” I tried to winnow that number by asking if he thought there were fewer than fifty. “Possibly,” he said. The numbers are so small that the entire trade could have been wiped out if a lastmaker sneezed hard enough during the height of the COVID pandemic.

In small, dying trades—including bespoke tailoring, shoemaking, and even ready-to-wear suit manufacturing—one often hears craftspeople expressing hope when they talk about one or two new people entering the trade. I recently spoke to a patternmaker about the slow death of the American manufacturing industry, where the number of American suit factories has diminished from an estimated 5,000 at the turn of the 20th century to five today. He mentioned that he recently heard about a British tradesman who’s learning how to draft ready-to-wear suit patterns. “There’s something sad about you are pinning your hopes on one guy,” I told him. We both laughed.

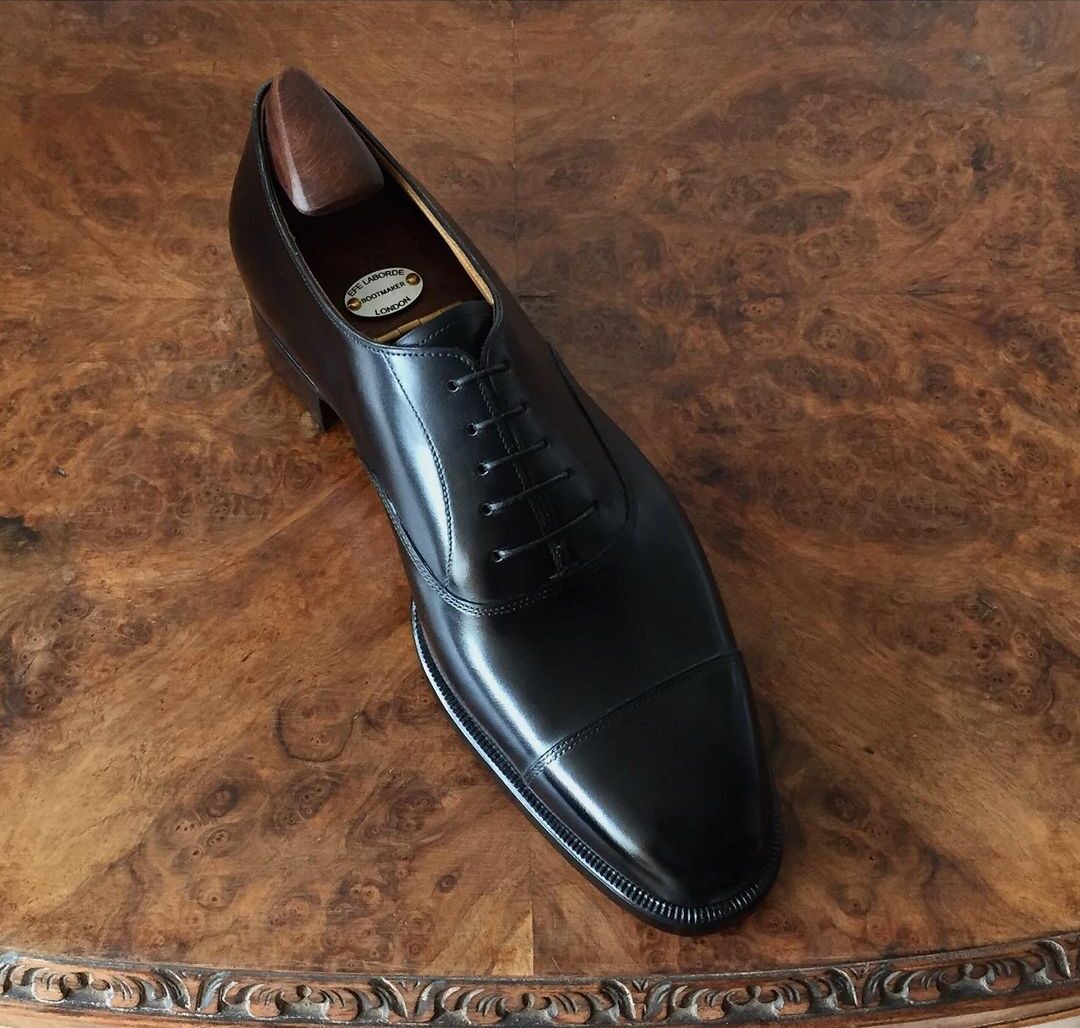

Among the more seasoned shoemakers, William Efe-Laborde’s name is whispered as one of these up-and-coming artisans in the British bespoke shoe trade. He came into the “gentle craft” by way of the art world, where he handled precious Piccassos and Monets while working for an art dealer. While mingling among the well-to-do, Efe-Laborde noticed that many men wore custom suits and shoes. “It got to a point where I was really keen on getting myself a pair of bespoke shoes,” he said, “but I couldn’t justify spending that kind of money. So I decided to try to learn how to make myself a pair, as I’ve always been interested in manual things.”

Before he could craft shoes, Efe-Laborde needed the right tools. So, he scoured second-hand markets for job lots containing late Victorian steel shoemaking tools made by a now-defunct British manufacturer named Jupp. The best tools, he tells me, were produced in the late 1800s. “Before the outbreak of COVID in the UK, I presented at a conference for independent shoemakers and showed three identical pieces of equipment,” he tells me. “You can also see how the quality has deteriorated over time, just like the shoemaking trade. It stands to reason that shoemakers would have had higher standards when shoemaking was a thriving trade and there were more tool manufacturers. Jupp was one of these manufacturers based in Soho, and they worked alongside the shoemakers they crafted tools for.”

Efe-Laborde has since established a small side business in which he purchases, restores, and sells Jupp-made shoemaking tools to other artisans in the trade. The business has gained him some inroads. Having already taken a nine-month shoemaking course from Carreducker in 2014, he has leveraged that foundation to learn more about shoemaking from experienced artisans such as Jason Amesbury, Jim McCormack, and Dominic Casey. Efe-Laborde is one of the many makers who has learned his craft by taking courses, reading shoemaking books such as Golding’s seven-volume set Boots and Shoes (1935), and relying on the goodwill of his peers, rather than taking an apprenticeship at a larger house.

I asked if it was not weird for other shoemakers to teach him their methods, as he could one day be their competitor. “Bespoke shoemaking is not an easy trade, but I think once you prove that you’re sincere and genuinely dedicated to this craft, others are happy to teach you what they know,” he said. “This was not always the case. It’s well-documented that shoemakers used to be very secretive. At some companies, bottom makers worked behind a curtain so their colleagues couldn’t see their methods. But in the current environment, if shoemakers don’t support each other, the trade is at risk of fading away. Ultimately, everyone is in this because they love the craft and want to see it survive.”

Although he’s relatively new to the trade, Efe-Laborde has an interesting theory for what has driven the changes in the British bespoke shoe trade. As he sees it, the story is ultimately about the demographics of who buys such shoes. “Bespoke shoes are a much more niche product than they were at the turn of the 20th century,” he says. “The clientele today is different, so the craftspeople have to adapt.”

“Think of who was buying bespoke shoes in the middle of the 20th century,” Efe-Laborde says. “It would have been someone who wanted a pair of handmade shoes that fit properly. But they probably didn’t take much interest in the number of stitches per inch, the height of the heel, or even the toe shape.” Such customers may have been part of the aristocratic Old Money class, where town and country gentlemen went to craftspeople to purchase custom-made shirts, saddles, canes and umbrellas, guns, fishing rods, gloves, and shoes. Such shops did not advertise. As Thomas Girtin noted in his book Nothing but the Best, “They depended on word-of-mouth endorsements from satisfied and generally slow-paying customers.”

As postwar England marched towards the end of the century, the makeup of the clientele at these houses changed. According to Girtin, by the early 1960s, over sixty-five percent of English bespoke shoes were exported to the United States, where newly minted business people were eager to get a taste of Britain’s aristocratic lifestyles. Efe-Laborde suggests the slide went further in the 1980s and ’90s. “The story isn’t that different from the art world, where Old Money slowly went away, and new Money came in,” he says. “For that Old Money customer, it would have been obvious if a pair of shoes didn’t meet a certain quality level because they grew up with such goods all their life. So even if they weren’t interested in the particularities of shoemaking, they would have known if something was terribly off.”

But as large bespoke shoemaking and tailoring houses have become increasingly dependent on New Money, the market has changed. Many have morphed into pseudo-brands, using their bespoke services to create a halo for a growing ready-to-wear line (perhaps necessary to pay for stratospheric Mayfair rents). There are also two types of bespoke customers: one who enjoys the prestige that bespoke confers and another who is obsessed with craftsmanship. “The second sort of customer is very different,” says Efe-Laborde. “They’re not exactly Old Money because they didn’t grow up with such things. As such, they’ve spent a lot of time reading and researching to acquire a certain kind of knowledge and level of taste. At the same time, they’re not like the New Money customer, who may not be as discerning. They’re a new type of customer. And there’s a new type of craftsperson—the smaller outfits—who are out there waiting for them.”

(Photos by Nicholas Templeman, Emiko Matsuda, Daniel Wegan, William Efe-Laborde, Peter Zottolo, Shoegazing, Dapper Made, and Maslowso)