Bespoke tailoring and the restaurant industry share something in that they both use the terms “back of house” and “front of house” to describe how their businesses are structured. “Back of house” refers to the behind-the-scene activities that customers typically don’t see, such as the cutters, tailors, chefs, and line cooks who prepare the things that are eventually given to customers. “Front of house” is a little different. In the restaurant industry, this term refers to the customer touchpoints, such as the waitstaff and host who work to create a pleasant experience. The front of a bespoke tailoring house, which can consist of salespeople and fitters, also provides those things. However, they also offer something more important: a sense of taste.

George Wang, the founder of the Beijing-based bespoke tailoring company BRIO, works the front of house. When you commission something here, you’re not just paying for the skillful craftsmanship that goes into each garment, but also George’s sense of taste. He’s the one who created the company’s overall aesthetic. He’s also the person who will guide you through decisions such as fabric choices and stylistic details. George tells me that each customer is different, and it’s important to be sensitive to a person’s needs, lifestyle, and even personality. A conservative businessman who needs a winter work suit has very different requirements than a young creative who wants something to wear to summer parties. It’s easy to trivialize this service now that there’s so much information on the internet, leading people to believe they can do everything independently. But over the years, I’ve come to appreciate how useful it is to work with a tailoring house that has both “front” and “back” staff persons (tailors, while wonderful, are better thought of as technicians than stylists). At Rubinacci, Mariano does the vital work of ensuring every client walks out of his shop looking “right.”

I often ask George for his opinion on things, such as the right fabric to use for a project, what color the lining should be in a folio, and what watch best matches a certain kind of wardrobe. He always gives me an answer that feels like a step above what I would have initially considered. Instead of the usual recommendations for linen, wool-silk-linen blends, and Fresco for warm-weather garments, he recommended to me slippery Super 150s wools in colors such as light blue, coral, and citrus yellow. He also turned me on to London Shrunk, as well as world-class makers such as Sartoria Corcos, Sartoria Marinaro, The Work, Saic, and Masahito Furuhata. In a word, I find his taste to be sophisticated. So, for the last entry in this series, I’ll start with George’s thoughts on how to develop good taste.

George Wang, Founder of Atelier BRIO Pechino

Like everything else in life, the process of developing taste is informed by experience. Since we’re discussing clothing or style, taste usually refers to a pleasing combination of colors, textures, proportions, silhouette, and, perhaps most importantly, context.

Colors: Nature is our best reference. On a biological level, thousands of years of human evolution have dictated what is pleasing to the eye. The Italians often say “azzurro e marrone,” which are the colors of the sea and the earth. Nature contains every color combination that ostensibly “works.”

Texture: This is one area where you must know what you are doing. It’s always safe to keep textures in unison, but the more experience and confidence you have, the more easily you can break the “rules.” Texture is about more than a fabric’s weave or material; it’s also about the visual weight. It’s difficult to put these things into words, so I recommend looking closely at Ralph Lauren and trying to understand his thought process when he wears unusual combinations.

Proportion and Silhouette: These are the easiest to understand. You can either adhere to conventional concepts or go the opposite way. But never somewhere in between. [Derek: readers may want to check out a series I wrote for Put This On on how to think about proportions and silhouettes. It covers both the conventional and unconventional.]

Context: A loose-fitting sweatshirt with a pair of vintage Levi’s and some beat-up Air Force 1s might be a good outfit for walking the dog on a Sunday morning. The same outfit, however, would not be appropriate for a date night at a formal restaurant. And the other way around. This is what I mean when I say context is crucial. Because how we dress in the modern world is entirely a social construct, you should always consider context. Understanding what is over- and under-dressed is critical for good taste. At the end of the day, unless you’re walking around with a mirror in front of you, how you dress is for the enjoyment of others, and they’ll decide whether or not you have good taste.

Finally, I’d like to emphasize that everything I’ve just said is an attempt to rationalize something almost entirely emotional, so don’t think of them as rules or conventions. What makes you happy or satisfied is perhaps the most important factor.

Aaron Levine, Designer

[Derek: When I interviewed Aaron Levine last year, we talked about his love for building miniature Gundam models (“It helps put my mind at ease,” he told me). This is the kind of hobby I’d expect from Asian nerds like myself, not stylishly dressed creatives who have designed for the likes of Abercrombie & Fitch, Club Monaco, and Hickey. But Aaron’s love for Gundam is just a glimpse into his eclectic taste. Aaron has a borderless view of the world and doesn’t talk about fashion in terms of rules, categories, or even aesthetics. Instead, he just talks about what he’s into at the moment and waves away any contradiction with the term “vibe” (e.g., certain things and people have good vibes). This attitude is reflected in the way he dresses. On Instagram, you can find him teaming 1980s Armani topcoats with hooded Arc’teryx jackets and military fatigues, oversized outerwear and pants with tiny shoes, and waxed Barbours with leopard print slippers. Somehow, everything always looks cool. He’s imaginative, creative, and a true thrifter. Aaron pushes me to think about clothes in new ways, which is why I wanted to include him in this series.]

It goes without saying that taste is subjective, and what I consider good taste may not be what someone else considers good taste. However, I believe that any definition of good taste must include some connection between what you wear and your identity. Otherwise, I think there will be a limit to how much you can enjoy wearing your clothes. People need to feel authentic; they don’t like feeling inauthentic. So, whatever your definition of good taste is, I believe you need a strong, magnetic, north-pointing compass in terms of your personal identity.

For example, as a child, I enjoyed mixing and matching clothes. Because I grew up outside of Washington, DC, everything around me was East Coast prep, Army Navy stores, and a touch of vintage. Surf shops were also appealing to me. So when I mash all of those things together, I get an aesthetic that I still follow today. That aesthetic influences my clothing choices, how I present myself to the world, and how our family decorates our home. Everything is intertwined. To me, good taste is more than just one aesthetic. It’s a vibe. It’s about being genuine, nice, and true to yourself. If you’re passionate about something and true to yourself, it will shine through to others.

I don’t believe that having good taste is as simple as purchasing the right lamp or wearing the right shirt. I’m also not sure I agree with the idea of good versus bad taste. People are complex and have many contradictions, even when they are true to themselves, and they evolve over time. For example, there are times when I want to watch Jaws and other times when I want to watch To Kill a Mockingbird. Sometimes I want to watch Guardians of the Galaxy. These are all very different things, but they’re all things that I genuinely enjoy. You can take bits and pieces from various aesthetics and still have them authentically reflect who you are as a person. It’s not always fun—or even true to yourself—to always have whatever others consider “in good taste.” When you’re authentic to yourself, you’re not chasing a mirage. On some level, I believe it is more important to be authentic and passionate than to meet some criteria of good taste.

Derek: One of the reasons I wanted to include you in this piece is that you frequently mix very different, and sometimes even contrasting, styles into your outfits. It’s sometimes a mix of heritage workwear and modern techwear. Sometimes it’s a heavy overcoat with delicate slippers. Your taste spans so many different genres. Yet, everything flows. Do you have any recommendations for someone who wants to be more playful with their taste?

This is something I frequently refer to when designing a collection with a team or creating a concept board. I like to have some tension somewhere. And the same goes for what I wear. If I dress head-to-toe and there’s no tension anywhere, I don’t feel like myself. I don’t want to use the word contradiction, but I do want to use the word tension. That tension can come from mixing different colors, prints, styles, or genres. I also love getting that tension from texture. It’s important to me that I feel like myself when I get dressed in the morning. And I need a little tension in my outfit to feel at ease.

Tension can be its own aesthetic. It may not be something you have naturally, but it is something you can cultivate. When I was working at Hickey Freeman, I often tried to work this into my designs, but I was flipping too many levers at one point. As a result, much of what I was doing came across as ridiculous. My mentor once pulled me aside and said, “Hey, maybe don’t flip so many levers, buddy. Limit yourself to a single color palette. Instead of using all these colors, how about sticking to navy and creating tension within a set of parameters?” That allowed me to be more low-key and sophisticated about what I was trying to create. When you learn to play with the nuances, you can create an interesting outfit without being the loudest-dressed person in the room.

Ultimately, whether you want to create tension in your outfit or not, I believe the most important thing is to learn how to express yourself authentically. The funny thing about taste is that it’s so personal. I’m surrounded by friends who I think have taste levels that are way above mine. When I see them, I often think, “Wow, I should try that!” However, when I try it, it doesn’t look as good. It lacks authenticity. This is where someone’s individuality comes into play—sometimes, things work for one person but not another. When you see an original versus a copy, you can always tell which is the derivative. Once you learn how to express yourself in a way that feels right for you, that will be your taste. Your clothes should feel like a suit of armor that allows you to present yourself in the best way possible.

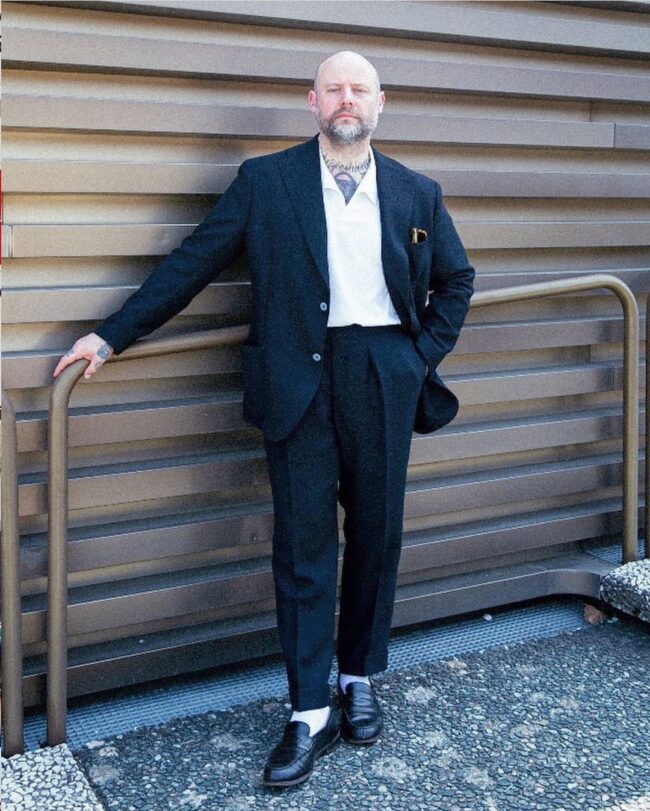

Tony Sylvester, Musician and Owner of AWMS

[Derek: I want to end this series with Tony Sylvester, who personifies many of the ideas I’ve tried to convey through this series. I wouldn’t say that Tony has “good taste.” To me, the term “good taste” sometimes implies the taste of a specific socioeconomic class (a class that has mostly lost cultural relevancy since the 1980s). I would say that Tony has excellent taste (a class-neutral term). Strictly speaking, Tony wears classic menswear items such as tennis sweaters, double-breasted blazers, tartan trousers, striped rubgys, bucket hats, and raglan-sleeved overcoats (many of his design under the label AWMS). Yet, his outfits lack the staid respectability that characterizes much of classic menswear (and what is often implied when people use the term “good taste”).

Instead, his outfits convey something completely and unmistakably him. Tony grew up in the hardcore scene of the 1980s and 1990s and is now the frontman for a Norwegian rock band. He’s an inveterate thrifter with a love for vintage clothes. His outfits communicate this identity and his style is shaped by the force of his persona. If you or I were to wear the same things, the message would not be the same. This speaks directly to what I’ve been trying to convey with this series: that people bring their persona to their outfits, that fashion is about culture, and that taste is about the relationship between persona, culture, and semiotics. Dressing well is similar to learning to write in your own voice in that you must learn how to communicate something while also doing so in a way that feels natural to you. Tony embodies what it means to have taste, so I’ll end this series with his thoughts on the subject.]

The concept of “good taste” has always elicited suspicion in me and made me a little queasy. Firstly, one is not allowed to attribute a sense of taste to oneself, in the same way that you are not allowed to describe yourself as (or God forbid, tag your Instagram photos) “cool” or “stylish.”

I’m not sure I have the character or physicality to be in good taste. It’s an accolade put on one by others, sometimes in good faith, but more often as a way of gatekeeping. It always feels to me like a test to be passed or patronage bestowed. I’m sort of aware of what “it” is, although it has always seemed nebulous at best, arbitrary at worst. I have joked with friends about The Tyranny Of Good Taste: an attempt to impose a standard at the expense of more personal expression, a great leveling in the name of propriety.

More seriously, I suppose I view the concept as a sort of plimsoll line on the side of the sartorial ship. Something I bob alongside, surfacing and submerging when the mood strikes. A deep-set contrarian streak causes me to often play a sort of brinkmanship with convention and taste. I have no doubt that I often bend it so far that it breaks.

The Science Museum did a fascinating study on the evolution of colors in their collection and how it has changed over the past 150 years or so. It’s summarised perfectly in this Twitter thread. Everything from cars to household appliances to home decor to clothing has lost its vibrancy and color over the past century. This corresponds to my experience of what is considered tasteful in masculine dress. From the fifty shades of greige at one end of the market to the none-more-black minimalism at the other. And perhaps my least favorite culprit: the entire aesthetic built off the common denominator of a pale grey New Balance 991, the most boring shoe ever made, demonstrative of an unwillingness to engage with color, pattern, and ultimately—crucially—the actual joy of getting dressed.

Over taste, I’d rather see people use intention. Even “discernment” feels like a value judgment. The term intention is neutral and implies implementing a skill set based on experience, knowledge, and, most crucially, passion. It is a personal process of awareness of oneself that trumps the concept of success or failure of the “fit” based on an observer’s perception.

If the ultimate purpose of dressing is to feel good or to take pleasure in the act of dressing, then why does taste even matter?

This concludes this series on taste. Of course, this series is not intended to be a road map for how to actually develop good taste, but rather a starting point for a larger discussion. In recent years, I’ve noticed that menswear discussions have become more about shopping than dressing. In a world where a million aesthetics coexist, old menswear rules seem antiquated, and we need better ways to think about how to dress and appreciate different aesthetics. This series began with a post about how I believe fashion is about semiotics and culture. I then solicited entries from stylish people such as Bruce Boyer, Mark Cho, Rachel Tashjian, David Marx, and the three people mentioned above on how they think people can develop good taste. I hope it inspires readers to think more about the subject, as taste is at the heart of our mutual love of clothing. My heartfelt gratitude to everyone who contributed!!!