It has become fashionable to discuss classic clothing with the same cynicism once reserved for topics such as capitalism or the media. Across menswear message boards, posters frequently type out terms such as classic or timeless with alternating caps (cLaSsIc) or recurring spaces (t i m e l e s s) to signal that they’re above such simple ideas. To be sure, traditional clothing has had a difficult decade. During the early months of the COVID-19 pandemic, some of the first companies to file for bankruptcy were suit retailers, Brooks Brothers among them. Additionally, men who invested heavily in soft-shouldered sport coats ten years ago have since traded their Aldens for Nikes, as they’ve found that tailoring is too formal for their environment. Looking back, many of the things championed as timeless, classic, and trend-resistant ten years ago—slim suits, cutaway collars, and double monks—barely lasted more than a few seasons. Meanwhile, designer labels such as Margiela, Rick Owens, and Engineered Garments have been selling the same styles since the early 2000s, as their clothes are too niche, conceptual, or expensive to ever reach mass consumption and thus over-exhaustion.

Timelessness is often oversold, but in recent years, I think the pendulum has swung too far in the opposite direction. It’s a mistake to think that terms such as classic don’t mean anything. Certain styles, such as trousers made with moderate proportions or oxford button-downs that fit and flatter the wearer, are relatively resistant to trends. Classic tailoring also holds a special place in our culture because it’s the lingua franca of menswear—a language everyone understands, regardless of their background. Many designer aesthetics require specialized knowledge to appreciate, such as the shabby look of Kapital or the sculptural quality of Issey Miyake’s futuristic creations. But almost everyone can appreciate how a man looks in a well-tailored, moderately proportioned suit because of what it represents in our collective memory.

When it comes to matters of taste, few people have a better record than beloved menswear author Bruce Boyer. I first saw Bruce online when Scott Schuman posted this photo of him on his site The Sartorialist around 2007. I was struck by the tastefulness of the outfit—a brown checked tweed with taupe trousers, a green striped tie, a light blue shirt, and a tan mac raincoat that reached Bruce’s knees. The thing is, Bruce dresses the same today as he did back then, and in every other photo ever posted of him. On the inside of the dust covers for his books Elegance (1985) and Eminently Suitable (1990), you can find black-and-white author photos of a younger Bruce not only wearing the same things—a semi-spread collar shirt with rep striped tie and either a navy double-breasted blazer or houndstooth tweed—but even clothes in the same proportions. In a Permanent Style feature, Bruce flipped over the in-breast pocket of one of his sport coats to reveal an Anderson & Sheppard label typeset with his name and the date “9/5/83.” Imagine never bricking a single fit for nearly forty years (possibly ever). So I asked Bruce: how does one develop good taste in clothes? His answer is below.

“Status and Style” By G. Bruce Boyer

I must first confess to no longer being as up on the scientific data in the nurture-nature debate, but I’ve always been a sort of democratic guy about such things. Early on, I bought into the essential American belief that our destinies are not written for us at our births, that our talents and tastes could only be formed by the influences of our experiences. And so I usually come down on the nurture side of the argument. It’s just more democratic.

Regarding taste and style, we derive those attributes from our experiences and the knowledge absorbed, digested, and reconstructed from the episodes of our lives. But the question is: can they be taught? It’s clear to me that they can and are, both consciously and subconsciously. When we’re young, we imitate those we admire, whether it be a beloved teacher, a particularly natty uncle, the older kid next door, or a college friend who had an uncanny elegant ease about him. For me, a few of the older guys in the neighborhood who dressed with a certain confidence and swagger got me to understand that style had its rewards. Someone who, as my friend Constantine Valhouli mentioned to me, “made us think about style for the first time and wonder what made them so visually compelling, and how we might apply those lessons to our own lives?” This means that, for many of us, style became a self-taught discipline starting with imitation. For me, it happened to be a decidedly conscious one because I felt I needed as many tools in my toolbox as I could find. And dress and grooming became my tools of choice. Maybe I thought they were the only ones available.

Taste and style are taught every day, whether on a particular group level (e.g., neighborhood, business, aspirational, etc.) or on the more ethereal heights of the fashion industry mountain, it’s more a matter of who’s doing the teaching and how it’s being taught. It used to be, in those golden years when highly visible logos acted as a guide for the clueless, that the vision and preferences of individual designers drove the seasonal production and, in turn, buying habits of many. But a recent article in The New York Times by Ross Douthat makes the case that algorithms are replacing designers in this process. This new approach is directed “by a combination of cheaper production models and forecasting systems that take the guesswork out of trends. The production churns out fashion; the algorithm doubles down on whatever sells the fastest.” I’ve noticed this myself, that algorithms give us more of what we’ve already liked (once you’ve watched one labradoodle video on Instagram or TikTok, you’ll be inundated with them) or encode existing biases. But fashion reflects society—at times, its shifts are gradual (the slow creeping up or down of hemlines, for instance), and at other times, they’re sudden and dramatic (as when a popular movie sparks a fad).

Algorithms might make things more efficient and minimize production risks for manufacturers (not to mention that whatever is being sold will drive the editorial conversation in print magazines and online), but they’re not exactly the ideal teaching tool to acquire taste and style, are they? We understand that this is exactly what virtually everyone in the fashion business is trying to do: convince us that if we wear what they tell us to, we’ll have impeccable taste, style, and eternal happiness. But of course, they keep changing their minds every few months and making us wonder if this is the worst use of democracy in our time. If people in the fashion industry believed in individuality, then why have trends?

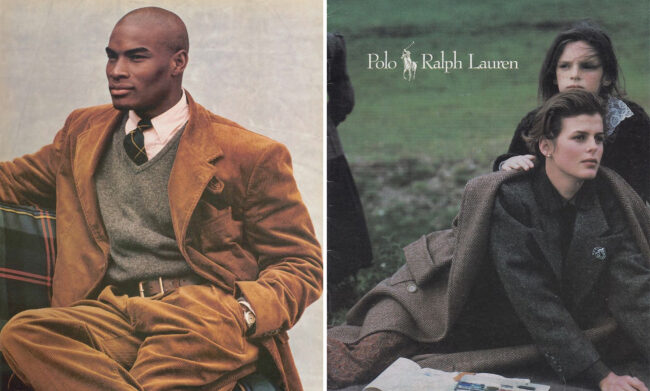

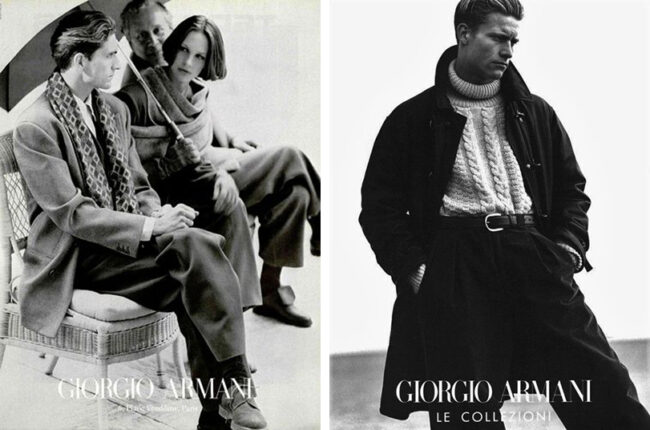

Fashion is a decidedly commercial enterprise. Naturally, the market is always dealing with competition, but today the market has become so competitive—the internet has made everything available to us—that products become nearly indistinguishable and must compete mainly on price, the most blatant aspect of the product. I believe this is called commodification. And so the gatekeepers of fashion, whether it be a magazine or blog site, designer label or a celebrity—and I think those are the main categories of the moment on which the public rely—there’s bound to be the algorithm feverishly at work trying to turn the Cool Hunt into a financial bonanza. Beginning in the 1970s and for a long time after that, the design genius of Giorgio Armani convinced many people to adopt his slightly louche Italian charm. Ralph Lauren convinced even more of us that our grandfathers owned mahogany speedboats, lived in Scottish manor houses, and drove ancient Bugattis instead of working in the steel mills of the East, stockyards of the Midwest, or shipyards of the West Coast. If today the designer has been replaced by algorithms, it’s merely confirmation that fashion today is VBB [Very Big Business], and fashion editors are merely members of the sales staff, and in bed with the advertisers. It seems somewhat silly to believe that clothes represent the individual when the design tool itself is only interested in trends. Different designers, of course, resonated with different groups [as Americans, we don’t like to use the word classes] depending on the message we intend to convey. These differences are based on a finely tuned predisposition of the human mind to find security in a group and distrust strangers. In other words, it’s a survival mechanism that combines nature and nurture.

So when we talk about taste and style, we’re not talking about fashion; we’re talking about the individual and his lifestyle, whether it’s given, chosen, or aspirational, and within the general confines of a group. One of the great achievements of American life, especially in the 20th Century, was that the class barriers were far more porous than they were in, say, England or India, and that we can all move UP if we’ve got the talent, gumption, and a good bit of luck. Today, of course, those assumptions have come into question somewhat. But as concerns matters of dress and our public image, the basic question is: with which group do we wish to be associated and identified? This becomes crucial in a world of rapid flux. In the past, designers such as Armani and Ralph Lauren gave us two different aspirational visions. The semiotic meaning of clothes, like meanings of words, depend on their usage. Appearance may be superficial and may not be the best way to judge others, but it’s often all we have in a fast-moving world where decisions are made rapidly. Think again of those aspirational images projected by the Ralph Lauren adverts. Visual images are immediate clues.

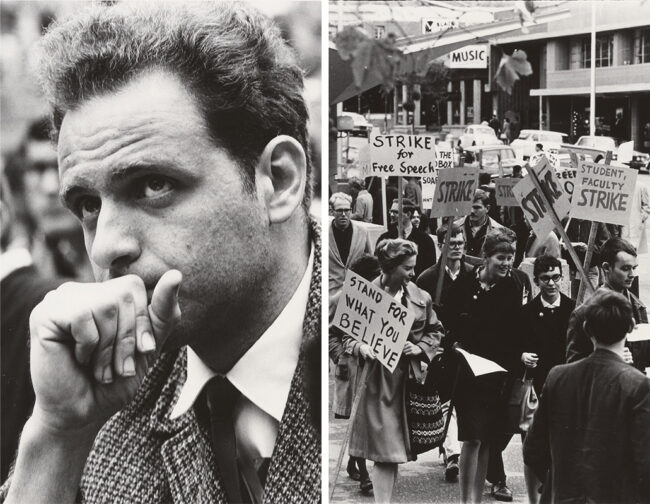

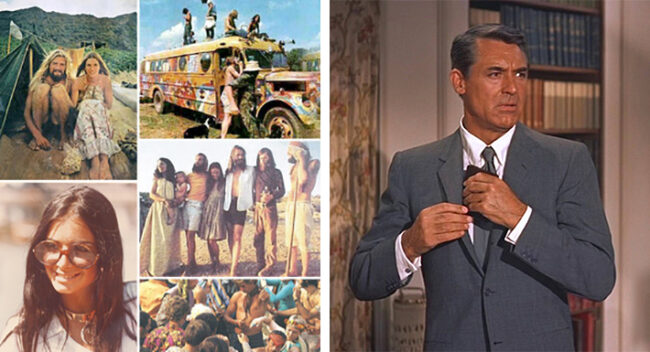

A quick personal story about that. When I was teaching in the late ‘60s and early ‘70s, I liked to attend student meetings of the New Left. My heart and mind were with the students, but because I wore a suit and tie—all of them were wearing distressed and decorated bell-bottomed denim, love beads, sandals, and traditional Indian shirts—I was at first thought to be a spy of the Establishment. Nothing could have been further from the truth; I was there to learn just as they were. Once this was established, they teased me about my “uniform,” and I could gently point out to them that they were all wearing uniforms of a sort, too.

Taste in appearance is dressing for one’s peers, whomever we think they may be. My uniform of coat and tie had one meaning among the faculty and a completely different meaning to the students. The same outfit, which was a social asset to one group, became a social liability in another. One man’s meat, as they say. We feel that style is the image of character, that it reflects the person himself, while fashion gives us ideas the designer wants the clothes to convey. And, I don’t mean to get all philosophical, if we strip away the clothes looking for the person beneath, it might be rather like stripping away the leaves of an artichoke looking for the real vegetable underneath.

My own style, if I may call it that, was related to the qualities I came to prize in my formative years—five to fifteen—growing up in a “blue collar” neighborhood of steelworkers and railroad workers, a typical American neighborhood in a small city in the middle of the 20th Century. Because it wasn’t the most financially secure neighborhood, the sense of respect was all that more highly prized—dignity and respect are always of the utmost importance when people have little else—and a person’s appearance became an indication of that. Even the poorest young men had a suit (and the accessories) to wear for special occasions like a party, dance, or going to a restaurant [not to mention formal occasions such as weddings, funerals, graduations, etc.], because tailoring was a symbol of success and thus respect. And my eye told me that some young men had something extra, a way of dressing, walking, talking, perhaps a particular way of gesturing or holding a cigarette that identified them as having style, that elusive word that spoke to a character and the psyche of the individual. I have been interested in clothes and how people groomed themselves since I was around five. What I was interested in before that I don’t remember; I probably just loafed about the house playing with my toys. But I understood early on that there were different social groups, and each had its own taste and style.

Since we’re talking about groups of influence, when we ask how a person develops good taste we become aware of the subjectivity of the question, how my idea of good taste may not be yours or theirs. On the other hand, we all envision ourselves as members of a group, even if that group doesn’t exist except in our minds—which group do you envision yourself in?—and on the other, we wish to establish ourselves as individuals in that group. People with “style” or “taste” usually have a strong sense of self and, whether they’re comfortable and secure within themselves or not, would like to signal something about their identity to others. We are known and want to be known—unless, of course, we really are spies—by our appearance, and that’s the whole point of clothes anyway, isn’t it? To identify ourselves at a glance to those who don’t know us, to make it plain in the social theatre what role we play. When we walk on the stage, we want it known what role we’re playing.

But even in a more general sense regarding image, how do you teach a person to be observant enough to pick up the intricacies and subtleties of dress and grooming, colors, patterns, textures, silhouettes, and details? And how to blend them into some coherent system that says what we want it to say? Are we sending the right signals? Are we being subtle enough for those within the group, and blatant enough for those without? Or are we sending confusing messages? These are deep waters, Watson. The easy answer is that we all (directly or indirectly, consciously or subconsciously) copy other members of the group, or at least use them as paradigms for our image. This form of dress can loosely be called fashion; we partake of a particular aesthetic and our allegiance to those norms we may call taste. That’s the broad answer.

Then the question becomes: what are your goals and how will you achieve them? I’ve done some image consulting in my time, as well as a bit of dogged research, and found that the best way to help people achieve their goals concerning their image is to get them to articulate what they believe that image actually is and then to sensitize them to the aesthetic’s finer points. We all wear uniforms of one type or another that speak for us. We believe doctors should look like doctors and skateboarders like skateboarders, and presidents should look presidential. Actors understand this very well when they put on costumes and cosmetics, they’re acutely conscious of the role they’re playing.

What do you want your physical presence to say about you for your role? It seems to me that’s the place to start. Consider your goals, dreams, and aspirations, and then try to dress accordingly. It’s maybe too much to say that sometimes playing against type and not blending in is what wins the day. This reminds me that P. J. O’Rourke had noted somewhere that if you’d decided to be, I believe the word he used was, weird, you should dress as normal as possible and vice versa. “When I see a kid with three or four rings in his nose, I know there is absolutely nothing extraordinary about him,” is how he put it. In 2012, Bobak Ferdowsi rocketed to fame when images of his spumoni-mohawk floated across people’s television and computer screens during a NASA Mars Rover landing telecast. He became a hero to tech people because he stood out amongst bland science folks as someone who was undeniably cool.

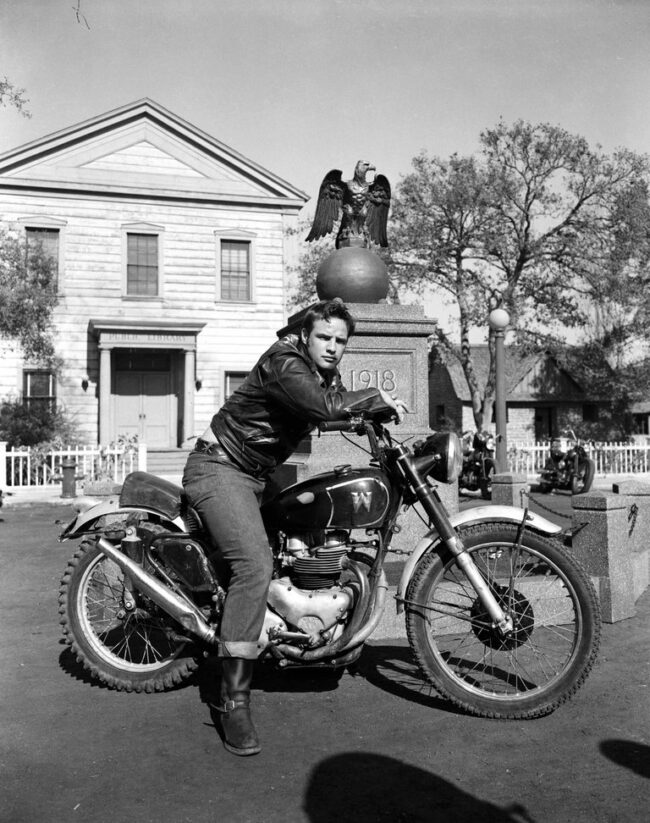

Short of taking a few courses in psychology, sociology, and acting, this is probably the point where someone who is articulate and reflective about clothes can help. Read sites such as this one, do a bit of exploration, go to a good clothing store, and ask many questions. For me, the endgame should be to make ourselves at ease with our chosen selves and send clear messages about who we have decided to be. To exude a sense of authenticity, we have to be comfortable with the person we have constructed—and make no mistake, everyone’s sense of self is a construct. Cary Grant is reputed as once saying, “every man wants to be Cary Grant. Including me.” I’m aware that this approach may run counter to many people’s belief that we each have an innate destiny, character, talents, and personality. I simply don’t believe that. I think most of us create ourselves from a tabula rasa in one way and another through our experiences, so many of which result in scar tissue and smiles. Sometimes those experiences include things we’ve seen (e.g., admiring a tweedy professor and wanting to adopt that style for ourselves) or the lessons learned from missteps along the way (e.g., realizing that leather jacket looked way cooler on the other person). I remember when I decided I wanted to be a professor—hairy tweeds and heavy brogues—I started to smoke a pipe, thinking it would help and be a nice pose for the hands as well. Unfortunately, it made me feel slightly queasy, and I had to give it up. Later I gave up thinking I should be a professor, although the image stays with me.

I’ve written on the nature of trad clothing, how to accumulate a workable wardrobe, and even how stylish men wear their clothes. In the early 20th Century, clothing was not yet seen as a costume, and it was only with the growing youth movement after World War II that a greater variety of roles came into play; upward social mobility wasn’t yet characterized by enormously quick gains in wealth—if I’m not mistaken, the recent lottery winner skipped away with something like $1.5 billion before taxes—and there was no internet. To be sure, there was already pushback against social and sartorial restrictions after WWI, as some men started donning soft collars and deconstructed jackets. But after WWII, the aspirational ideal started to show its greater cracks, and “taste” was no longer imposed by the upper classes. The middle and working classes had their own taste and style icons, celebrities for the young and old, which were recognized and marketed with specific product lines. Many men who wore a coat and tie in the ‘40s and ‘50s did so reluctantly and, when given a chance to go more casually, did so with great enthusiasm. By the 21st Century, the internet has radically increased the pace of The Cool Hunt, and in the past two decades, “fast fashion” has accelerated things to a breakneck speed. This is where the algorithm has played an important role in giving people what they want rather than having taste imposed on them. The truly well-dressed people, the ones with taste, have always been a significant minority. Some would say that, after all, hasn’t that always been the whole gamesmanship point of money and taste? Nevertheless, taste may require some innate talent to start, but it certainly requires teaching, nurturing, and a lot of observing to refine.

So, where does that leave us? Well, it leaves me with a set of simple rules that I think describe and even define my own “uniform.” These rules are not universally applicable. I’ve just tried to list them to somehow encapsulate my perspective and illustrate how I think about my own dress. Learning about clothes isn’t just deciding which garments to wear, but how to wear them, which is more complicated. And the only advice I can give here is of a general nature, but hopefully, it may be found useful. The key to style isn’t found in those technical aspects of dress that most fashion writers and style books are concerned with. It’s in the individual mannerisms that collectively suggest the wearer’s personality. This is why it’s often said the style is the man; to phrase it differently, style is the outward sign that reveals the psyche. For myself, I find I follow a few simple rules when I buy clothes and wear them. I think these rules can apply to a variety of tastes and styles, from Savile Row suits to streetwear.

- Simplicity is usually a virtue, and it’s better to be underdressed than overdressed. No point in putting all the goods in the shop window.

- Buying trendy gear is the most expensive way to dress and doesn’t result in suggesting taste or conveying a sense of style. Avoid fads and gimmicks, they’ll be gone soon enough, and you’ll be stuck with a load of expensive stuff that can only date you. The tough part is seeing through the editorials and advertisements that tell you that this particular little item is sexy and cool and will make you the toast of the neighborhood.

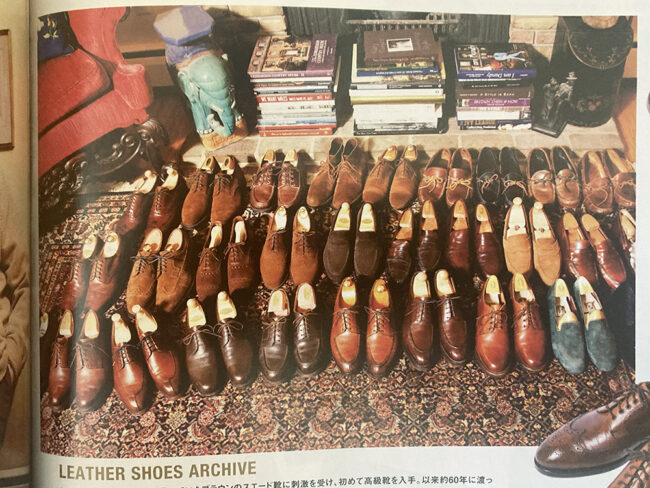

- Buy the best you can afford. it’s less expensive in the long run. Invest in quality unless you’ve got so much money you simply don’t give a rat’s proverbial.

- Insist on comfort from your clothes. If you’re uncomfortable, it shows, and you’ll make others feel uncomfortable.

- There is such a thing as appropriateness. It’s part of the social contract we hold with others to respect the occasion, purpose, setting, and company in which we find ourselves. If you’re dressed like a clown, the only thing you’ll find is a circus.

- Know yourself and signal that clearly. Clothing reflects who you are, how you see yourself, and how you want to be seen.

- Accentuate your assets and diminish your liabilities. But never use camouflage. Be proud of what you are, and learn what clothes can do to help what nature has given you.

I also find that the mistakes most men make fall into a few categories.

- Being too studied. You know, where everything is all matched up and color coordinated. Men who worry about this invariably appear overly fastidious, narcissistic, neurotically fearful, or merely blandly correct and predictably dull.

- Avoid too many “interesting details,” too many accessories, too much jewelry, or too extreme a silhouette. These things call attention to themselves, and no one sees you.

- Funnily enough, the opposite is equally true. Understated should not mean boring; distinguish yourself by whispering your individualities. People tend to shout when they can’t get attention any other way.

- Too many patterns and colors overload the circuit and burn the retinas. Better to stick to a few pleasing and flattering colors and use accenting ones in smaller accessories.

In sum, clothes are used for our security within the group, our place in society’s pecking order, and a bit of self-expression thrown in to tell others who we are. On a personal level, once I discovered that clothes could be used as a weapon to fight the slings and arrows of outrageous fortune, it became one of the defensive elements available to me. I nurtured this device, experimented with it, and came to understand how I could use it effectively. And it’s helped me out of many tight spots and led me into many lovely situations. I have no doubt it can do the same for you.

(You can read more of Bruce’s writing by purchasing one of his books. My favorites include Elegance (1985), Eminently Suitable (1990), and True Style (2015). They’re among the best menswear books ever written, largely because of how expertly they balance practical dress advice with observations about culture. Additionally, while most menswear books published during the 1980s and ‘90s seem terribly dated today, Bruce’s advice has aged incredibly well. His earliest book, Elegance, could have been published yesterday without changing a page. For more of this series, check out parts one and two. The fourth and final part will be published in a few weeks. Finally, I will be on Blamo! Presents in a few weeks to talk about this series.)