Style is still something of an art and has not, in Bruce Boyer’s words, “descended to one of the sciences.” The process of developing taste is akin to developing a worldview or personal philosophy—it’s a highly subjective process not easily given to hard rules. But over the years, I’ve noticed that people who’ve been able to develop tasteful wardrobes in a short period of time often rely on the gentle guidance of tasteful merchants, tailors, and friends. So for the remainder of this series on how to develop good taste (part one was published a few weeks ago), I’m surveying stylish people on how they think others can develop a similarly keen sense of aesthetics. Consider these entries like gentle advice from a friend who has the kind of high taste that almost seems unreachable.

When I first considered who to include in this post, I immediately thought of Mark Cho. Mark is the co-founder of The Armoury and someone I occasionally turn to for wardrobe recommendations. But it was his interview with WatchBox Studios a few years ago that made me want to get his views on the broader subject of taste. In the interview, Mark discusses his watch collecting journey, which started many years ago with an affordable Omega Chronostop he purchased at a second-hand watch store in Hong Kong. He was drawn to the watch for two reasons: he liked the shape of the case and had never seen a gray watch before. That purchase sparked in him a horological passion, and he was soon obsessed with collecting the milestones and classics in watch-making history. But as he’s chopped and changed his collection over the years, he’s found that almost none of those iconic pieces have remained. Instead, his watch collection is just a reflection of his taste, which is threaded together by nothing more than his emotional connection to objects. Having seen and handled thousands of watches since that initial Omega purchase, Mark has also developed what art dealers call The Eye—“that irrevocable power to discern art from trash, real from fake, inspired from derivative.”

There’s no better representation of what it means to have taste than Mark’s tantalum and steel Royal Oak. Originally made to celebrate Nick Faldo’s 1990 Masters and British Open back-to-back championships, Mark purchased it in 2013 because he wanted a baby version of the jumbo-sized Royal Oak 5402. But the only way to achieve that smaller, thinner profile was to get a quartz movement, which the Faldo version houses. High-horology purists would probably frown on the idea of spending thousands of dollars on a quartz movement, but Mark didn’t purchase his Royal Oak as a flex or an “anti-flex”—he simply wanted a smaller version of that design. “The Royal Oak used to be the watch no one wanted, and the quartz even less so,” Mark told me. “In the US, many people considered that watch too small, almost like it’s a ladies’ watch.” True style means dressing like you know yourself, and having the confidence to wear things others might dismiss as uncool. At the same time, it requires cultural awareness and sensitivity to the social meaning of your aesthetic choices. I love that Mark’s Royal Oak captures all of those things, so we’ll start today’s post with his views on how to develop good taste.

Mark Cho, Co-Founder of The Armoury

Taste, to me, is about understanding and making decisions about aesthetics. In the most common sense of the term, taste is about expressing yourself. However, it can also extend to the choices you make on behalf of others. People with good taste are often able to empathize and understand other people’s aesthetic preferences. I also believe that taste is fundamentally about coherence, and I compare it to communication. I know Derek Guy, who asked me to write this piece, feels the same way. Language is one of the most straightforward modes of communication. When you say something, the person you are speaking to will form an impression of you based not only on what you say but also on how you say it. In this sense, clothing is a visual form of communication. The items you use and how you combine them correspond to vocabulary, grammar, and syntax. This analogy also implies that taste can be taught. Mastering this visual language translates to mastering your aesthetic self-expression. No one is born with this mastery, but they can learn how to be better at it.

How does one develop good taste?

Bespoke shoemaker Yohei Fukuda put it best when he said: “To be a good craftsman, you have to have good eyes.” He means that you must learn to notice things in a very focused and deliberate manner. Since there is so much to process when you’re looking at something new, you will never be able to pick up on all the nuances. However, if you study things carefully, look at them for an extended period and compare them to similar items, you will begin to notice what distinguishes them as unique or ordinary. Pieces that were conceived haphazardly become especially obvious. Similarly, it is difficult to appreciate literature if you have only read one book. However, if you have read many books in various styles, your appreciation will grow, and your writing will be clearer and more expressive as a result.

Beyond simply looking at things, I believe it is even more important to fully experience them. When it comes to clothes (and even watches), this entails trying them on and, ideally, owning them for a while. When I first started shopping for clothes as a teenager in London, there was almost nothing available to me because no one made clothes in sizes 34/36. You couldn’t just walk into a store expecting to find something. As a result, I had to look much harder than the average British person for anything that physically fit, let alone looked good. I attribute a lot of my knowledge of clothing to this early experience. When I was looking for clothes in the 1990s, there was no menswear community online; you were left on your own to figure things out. So, I would go from store to store looking at different items. Many of the things I came across lacked something: maybe fit, maybe color, maybe design. However, every now and then, I’d come across something fantastic that made all the searching worthwhile.

When it comes to buying things, I’m fine with buying on impulse. Sometimes, I’ll give it a day or two to see if my initial enthusiasm holds, but I’m very comfortable buying things on a whim. If the purchase works out, that’s fantastic; if it doesn’t, don’t let it bother you. There’s a Chinese phrase for when you lose money on something that translates to “paying school fees.” I’ve paid a lot of school fees, and I don’t consider any of it wasted money. Even through the mistakes, I’ve learned a lot. It’s nearly impossible to know if you will like something until you own it. Conversely, I think obsessing over an item but never actually owning it is quite detrimental to your ability to enjoy it if you finally get it. It’s easy to become obsessed with something on the internet, but doing so can lead to unrealistic expectations that are impossible to meet.

People just starting to build a better wardrobe or watch collection often focus on “versatile” items, which is a perfectly fine and helpful starting place. You can’t run until you walk. But to develop taste, you also have to take chances and go against the grain sometimes. If your goal is self-expression, then a one-size-fits-all, best-business-practices approach will never get you there. Enjoy having different things for different seasons, situations, and occasions while keeping in mind what’s best for you. Relish the idea of having flannels for the winter, linens for the summer, small gold dress watches for special occasions, and robust, sporty divers for day-to-day adventures. Not using something every day is not a waste. On the contrary, using that item at the right time can make it much more special.

Accept that your preferences will shift. Nothing is eternal. That Royal Oak that everyone seems to want will most likely not hold their interest ten years from now. Today’s perfect navy blazer may require an update later. It’s OK! Accept your changes and use them to broaden and develop your palate. If you’ve been paying attention from the beginning, you’ll make even better decisions in the future.

Finally, I’d like to stress one more point: coherence. I believe your clothes should be coherent in terms of how they form an outfit and reflect something about you. Mesh tank tops with black silk tux jackets may not be coherent for you, but they may be coherent for Freddie Mercury. Pale yellow shirts and small gold watches are coherent for me. Black leather jackets and ripped black jeans are not coherent for me. At the end of the day, the clothes you wear should be such an accurate representation of you that, if someone saw them in a pile, they’d instantly recognize them as yours. You always look your best when you and your clothes are in sync.

Thanks for reading. May you all find your way.

Rachel Tashjian, Fashion News Director at Harper’s Bazaar

[Derek: Rachel Tashjian’s invite-only newsletter, Opulent Tips, is the most aptly named fashion content in the world. Every time I click a link in one of her emails, I think to myself, “ok yea that’s pretty opulent.” Her newsletters mostly cover womenswear, but every edition has something for everyone. She’s recommended the menswear side of Anatomica twice (particularly the high-waisted trousers made with side-adjusters), given numerous tips on how to throw the perfect dinner party (get lots of wine and pre-mix martinis so you can clap eyes on your guests; invite one “entertaining talker” to set the tone; serve food on porcelain printed paper-plates if you don’t have fancy plateware; employ charm and be thoughtful), and listed opulent reading recommendations (Evelyn Waugh’s Brideshead Revisited and A Handful of Dust, Jean Rhys’s Quartet, Toni Morrison’s Jazz, Nabokov’s Speak, Memory, the big book about Elsie de Wolfe’s Paris, Joan Collins Prime Time, Genevieve Antoine Dariaux’s Guide to Elegance, Joan Juliet Buck’s memoir, and more). I mostly love reading Rachel’s writing because she’s deeply knowledgeable about fashion, but she writes with the energy and enthusiasm of someone who just discovered nice clothes. She has a kind of sophisticated taste that I wish I could absorb second-hand. In one of her New Yorker fashion columns, Kennedy Fraser once wrote, “[I]f elegance ever did exist, we have lost our ability to recognize it.” I read Opulent Tips to train my eye.]

Hmm. Yes. Well, I have said this so many times that I might drive everyone crazy, but I don’t care because I think it’s so important: we need a complete reimagining of the way that we relate to ideas and objects. We have such a broken relationship to stuff. And most of the ways we hear about fixing this—focusing on sustainability! Following better Instagram accounts! Throwing out everything! Throwing out nothing! Cutting out the middle man with direct-to-consumer businesses!—are way too shortsighted. I think this is a spiritual issue, honestly. We don’t just over- or undervalue things but completely misunderstand how we should live and be with things. I don’t think there is one way for everyone to solve this problem; maybe we just all need to be more skeptical, or more tender towards ourselves (don’t we freaking deserve nice things and good ideas?), or more curious, or more patient. I feel very frightened by the way that a lot of the platforms we use to find information, which I use and like a lot, also encourage us to think the same ways and enjoy the same things. I look at something like Bama Rush, and I feel very scared that it is a product of and promoter of women all doing and wearing the same things. I know I sound crazy, but I can’t help how I feel! I think individuality is chic—individuality is self-respect! I think the more I came to realize that, the more I found my ways to things that delighted me, that I think are important to pay attention to, that make my relationships better and my work more interesting. I’m sorry to sound so theoretical about all of this but offering steps to developing taste goes against developing taste! That’s why everyone loves, for example, Vreeland’s Why Don’t You…? column, because what it is, essentially, is an invitation to dream and live with a sense of joy and freedom beyond what seemed possible the moment before you turned the page. To develop good taste, I think, you simply have to grant yourself imagination.

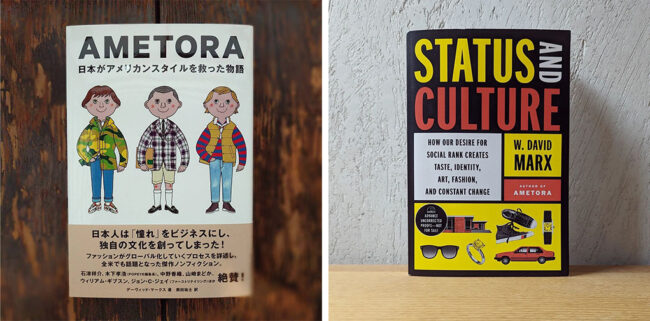

David Marx, author of Ametora and Status & Culture

[Derek: David Marx is the best menswear writer of my generation. The problem with most fashion books is that they often fall into one of two categories. There are general audience books that feel like nothing more than Wikipedia factoids and licensed images clumsily cobbled together like patchwork shirts. Then there are academic books that read like impenetrable tomes. Marx’s new book, Status & Culture, straddles these two extremes. It’s smart but accessible, engaging without being fluffy. Status & Culture examines how our pursuit of social status shapes our most profound personal desires and drives cultural change. Marx draws from sociology, anthropology, psychology, economics, philosophy, semiotics, cultural theory, media studies, and neuroscience, and keeps readers engaged with unexpected pop culture anecdotes such as Larry the Cable Guy and Lassie. The book also gets into why culture feels so stuck at the moment, and era-defining trends have given way to fleeting fads. Anyone interested in taste—and culture at large—should read this book.]

The first thing to understand is that “good taste” is a judgment that others make about you, and they will come to that conclusion based on summarizing all of your observable lifestyle choices. In this day and age, there is no longer a single, authoritative standard of “good taste;” each community has its own standards for what identities are afforded esteem, and taste is the vehicle upon which they judge “who you are.” So good taste requires two things: (1) Proposing an identity that happens to be valued in your community of choice. (2) Using your lifestyle choices to clearly, congruently, and authentically communicate that identity. Both are key. Being the most congruent, authentic Juggalo of all time may be “good taste” among Juggalos, but is unlikely to win you points in the comments section of Permanent Style.

Based on the definition above, the mission for each individual is very clear: (1) conceptualize the specific identity you aim to create, (2) learn the full meanings of every possible choice, especially the choices’ associations with specific people and groups, and (3) finally make the lifestyle choices that all work together to tell a congruent story of your aspirational identity. Yes, there are infinite options, but the more you know, the better your taste will be. In particular, it’s very difficult to be original unless you know what’s already been done.

In most communities, having “good taste” requires simply the skillful execution of pre-existing patterns and rules. To have great taste means creating new options or combinations that had not been previously considered to be “acceptable” and yet elicit delight from others.

[Derek: An introduction to this series can be found in an earlier post. Check back in a week or two for part three, which will include more entries from stylish people.]