At the Sotheby’s auction house in Hong Kong, a man in a dark blue suit shouted into a microphone as hands kept rising, pushing the price of Zao Wou-Ki’s triptych masterpiece, Juin-Octobre 1985, ever higher. Initially commissioned by I.M. Pei for his Raffles City complex in downtown Singapore, the painting represents the artist’s “Infinity Period.” Across three giant canvases, warm hues of peach, saffron, and lilac silently danced and exploded along a horizontal axis, giving the viewer a sense of the cosmos. In 2005, the painting was taken down from its Raffles City location and sold to a Taiwanese art collector. Then in October 2018, it appeared at this port-city auction house. That night, as arms flew up — many sheathed in silky worsteds, black lambskins, and gauzy blouses — the price kept climbing. By the time the hammer fell, the price for this marquee piece had landed at a staggering HK$450 million (US$65 million), setting a new record for an art piece auctioned in Hong Kong.

Born in Beijing in 1920, Zao was the scion of a prosperous family. His father was a well-heeled banker; his grandfather held the title xiù cai, which signaled a certain level of success in Imperial China’s civil service examination. Zao’s family encouraged him to follow in his father’s footsteps and pursue finance, but he had artistic ambitions. As a teen, Zao spent his days clipping images out of European and American art magazines, and pleading with his family to allow him to attend art school. His parents relented, but not without requiring him to at least get a classical Chinese education. So in 1935, a young Zao went to to the China Academy of Art, where he spent six years studying calligraphic ink painting. Upon graduating, he spent a few more years there as a teacher. Then in 1947, as the Chinese revolution drew nigh, Zao hopped on a plane and flew to Paris, intending to pursue two more years of art education.

Even as Paris was lifting itself out of the wreckage of the Second World War, the city had a vibrant and flourishing art scene. Much of this was thanks to the diversity already present in the French capital. Before the war, Paris attracted talented sculptors, painters, and printmakers from around the world. Many of these immigrants were young Jewish men who resettled on the Left Bank of Paris, where artists, writers, and philosophers gathered in cafes, salons, and galleries. Such artists included the great Amedeo Modigliani (an Italian painter known for his sleek and beautiful portraits), Marc Chagall (a Russian-French pioneer of modernism), and Chaïm Soutine (a tailor’s son whose impressionist portrait of a woman has since become a symbol of democratic protest in his home country of Belarus).

View this post on Instagram

The success of these artists drew resentment from a section of French society, who feared that immigrants were corrupting the purity of French art. In a 1925 issue of Comœdia, André Warnod used the term “École de Paris” (School of Paris) as an epithet for these foreign-born artists. The acerbic Louis Vauxcelles, who coined the terms “Fauvism” and “Cubism” (again, initially intended as an insult), must have been sneering when he described emigres dotted along the Left Bank as “Slavs disguised as representatives of French art.” “[T]he resentment expressed toward them by French critics in the 1930s was unquestionably fueled by anti-Semitism,” Wendy Smith wrote of the period in The Washington Post. “[T]he resentment this sparked in gentiles and assimilated French Jews was related to the decision at the 1924 Salon des Indépendants to group artists by nation of origin, separating the works of French-born artists from those of immigrants.”

Although France still struggled with xenophobia and anti-Semitism after the war, ethnonationalism was largely discredited within the art community after Paris’ liberation. When Zao arrived in Paris in 1947, it had only been three years since General de Gaulle led a triumphant parade down the Champs-Élysées. Yet, the art scene here was already thriving and increasingly accepting of foreigners. Zao’s intended two-year stay became permanent, and he reveled in his ability to surround himself with art that he had, up until this point, only encountered through black-and-white magazines. Zao was also warmly embraced by Paris’ cosmopolitan art community. The Chinese painter became friends with the Americans Sam Francis, Joan Mitchell, and Norman Bluhm; Portuguese Maria Helena Vieira da Silva; Canadian Jean-Paul Riopelle; German Hans Hartung; and Frenchman Pierre Soulages. The Belgian-French poet Henri Michaux introduced Zao to Pierre Loeb, an influential art dealer. In 1953, a group of these artists gathered in Loeb’s gallery, where Denise Colomb shot their portrait, immortalizing their friendship and this monumental period in art history.

Influenced by the Parisian avant-garde, Zao wanted to make his own way in the Western art world. He didn’t want to fall victim to a stereotype and be pigeonholed as a “Chinese painter,” so he distanced himself from the “overtly Chinese” landscape and ink painting techniques in which he had been trained. At the same time, Zao wanted to stay true to himself and not be just a cultural imitator. Eventually, he found his voice by marrying two disparate traditions — the post-war modernism of Europe with the classicism of China. At first glance, Zao’s abstract artwork can seem disorderly. Masses of color stretch across canvases and form new worlds like the Big Bang. Yet, every composition has a unique structure, which Zao organizes through lights and shadows. He uses strong, deliberate brush strokes, which recall his training in Chinese calligraphy, and thin, sinuous lines that hint at speed and motion, not unlike the feeling one gets from looking at a Jackson Pollock painting. When an artist friend found out that Julia Grimes was doing her UCLA doctoral dissertation on Zao’s early artistic career, he mused that Zao’s work isn’t “really representative of either French or Chinese art.” “Yes,” she replied. “He represents himself, and that is enough.”

View this post on Instagram

Zao’s story reminds us of the power of cosmopolitanism. “Everybody is bound by tradition,” he once reflected. “I am bound by two.” By combining two disparate traditions, Zao created something new and beautiful. Cosmopolitanism is about transcending the local and being open to the larger world, so that we may find a greater truth (or, in this case, beauty). The idea is as old as the ancients. At his family’s chateau just outside of Bordeaux, Montaigne had Terence’s words inscribed into the rafters above his study: Homo sum, humani nihil a me alienum puto (Latin for “I am human, and I think nothing human is alien to me”). When Socrates was asked which country he belongs to, he didn’t answer “Athens,” but “the world.” In a Spring 1711 issue of The Spectator, British essayist Joseph Addison delighted at the dizzying scene of multi-ethnic strangers rubbing shoulders with each other in London. “It gives me secret satisfaction, and in some measure gratifies my vanity as I am an Englishman, to see so rich an assembly of countrymen and foreigners consulting together upon the private business of mankind […] Sometimes I am jostled among a body of Armenians; sometimes I am lost in a crowd of Jews; and sometimes make one in a group of Dutchmen. I am a Dane, Swede, or Frenchman at different times.”

In the last hundred years, cosmopolitanism has seen its challenges. It’s sometimes dismissed as the ideology of the Western bourgeoisie, the weak, rootless, and unmoored, and those unwilling to assert a strong national character. But as Zao shows, one doesn’t have to sever their roots to embrace other communities — sometimes different traditions can come together to form something new and better. In the world of men’s style, cosmopolitanism often produces better dressers. Zao himself was tremendously stylish (as were all the artists of Paris’ avant-garde). The Chinese modernist knew how to wear classic Western pieces such as pleated cords and buffalo plaid hunting coats with panache. In modern Japan, Yukio Akamine and Kenji Kaga have cited men such as Vittorio De Sica and Fred Astaire as their style inspirations. When Gennaro Rubinacci started his family’s tailoring company in Naples, he originally named it London House after the city he admired most. Even Bruce Boyer, a trad among trads, wears The Armoury’s Model 3 — a Japanese suit inspired by Florentine tailoring.

George Wang, founder of BRIO and one of my favorite cosmopolitans in the men’s style community, recently opened the doors to his latest tailoring project, Atelier BRIO Pechino (BRIO and Pechino being the Italian words for panache and Beijing, respectively). The space is small — roughly half the size of BRIO’s old location — but George has made efficient use of it. When you walk through the doors, you’re faced with a cutting table, where BRIO Pechino’s tailors draft patterns like architects at their desks. To the left of the store, there’s a charming barbershop; to the right, there are storage spaces, where you’ll find a small line of luxuriously made ready-to-wear. The black-and-blond wooden furniture you see around the shop was imported from Italy, where it used to sit at Simone Righi’s Frasi boutique before it closed. George paid about $10,000 to have this heavy furniture shipped from Florence to Beijing. “It was like shipping an entire store,” he told me. But he reasoned, “Frasi was one of the best men’s stores in the world, and I’ll always have use for this furniture, even if it’s in my home.”

Although the store carries a small line of ready-to-wear, it’s primarily focused on custom tailoring. Stepping past its glass-and-wooden doorway is like stepping into a transporter, through which you can work with an international roster of artisans. BRIO Pechino works with Sartoria Dalcuore, a small Neapolitan tailoring house that specializes in the soft-tailoring style characteristic of the region: a thinly padded shoulder line combined with a clean chest, sweeping quarters, razor-sharp lapels, and a high gorge. From the north of Italy, there’s Sartoria Cresent, which serves as Naples’ geographical and stylistic opposite. Satoki Kawai, the founder behind Cresent, cuts a fairly square shoulder, swelled chest, closed quarters, and lower gorge that’s typical of Milanese style. BRIO also works with Sarto Jun (Seoul), W.W. Chan (Hong Kong), and Lutays (Paris).

The heart of BRIO Pechino is an in-house bespoke tailoring service that George has been quietly working on for about five years. In 2016, George convinced a well-regarded Florentine bespoke tailor to draft him a block pattern. He then gave that pattern to his two Beijing-based BRIO tailors to create several test jackets. Over the next few years, George and his tailors kept refining this pattern — creating new jackets, tweaking the silhouette, and getting feedback from Neapolitan and Milanese bespoke tailors whenever George went abroad for business. Last month, they debuted that service when they opened the doors to Atelier BRIO Pechino, and in doing so, showed what can be described as a distinctive Chinese tailoring style.

“It’s my vision of a contemporary look that sits within the world of classic tailoring,” George explained to me. “I want to take a more abstract approach to designing a jacket. When we think of British or Neapolitan tailoring, we often think of certain details, such as the ‘shirt shoulder’ or extended front dart. These things don’t necessarily add up to style; they’re just a reflection of a tailor’s training. But when customers look at jackets today, they often look for these very superficial details. They don’t think about the more important dimensions, such as a jacket’s silhouette. I want to bring the attention back to what’s important — the curves, proportions, lines, etc. I don’t ever want our jackets to be easily identifiable by their buttonhole or the placement of the darts. I want them to be identified by how they look as a whole.”

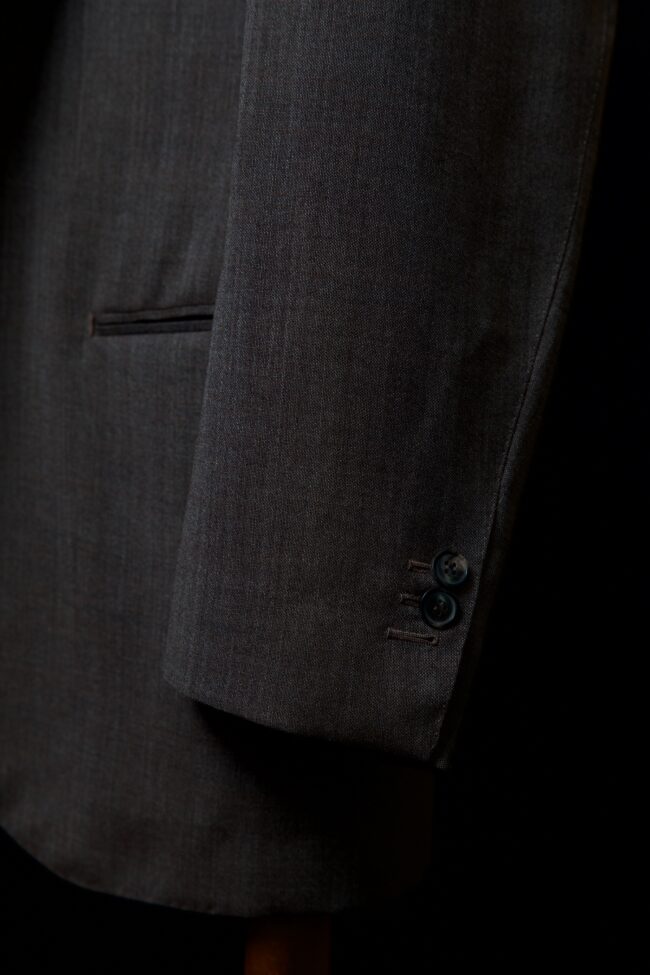

There are some things about the new BRIO Pechino style that feel very “George.” Born in China and raised in California, George spent much of his post-college years traveling around the world to commission custom suits and sport coats from Italian tailors and buy ready-made clothing from little-known shops in Japan. His in-house tailoring service feels like an accumulation of those experiences. Like Zao’s artwork, BRIO Pechino’s tailoring plucks what’s good from the larger world, and then turns those elements into something that can be called their own. BRIO Pechino’s jackets have very little structure — no padding inside, just haircloth that extends over the shoulders. This construction gives the jackets a certain lightness and comfort, which will be familiar to anyone who has worn southern Italian tailoring.

Yet, the jackets don’t look Italian. They have an extended shoulder line that’s vaguely reminiscent of Florentine tailoring and George’s personal style, but not the cropped length or rounded silhouette characteristic of Liverano. The buttoning point has been lowered, extending the lapel and lowering the jacket’s center of gravity. When worn, these jackets almost look as though they’re dripping off the wearer’s body. Since the buttoning point has been lowered, the jackets have also be lengthened to keep a balance in proportions. George strongly feels that jackets nowadays are too short. “When the jacket is short, the pockets have to be higher on your body,” he explains. “Which means, when you use your pockets, your arms are heavily crooked and your shoulders are squared up. You end up looking stiff and unnatural. Conversely, when a jacket is longer, you can place the pockets lower on the person. This way, when you have your hands in your pocket, you look more relaxed and laid back.”

“Relaxed” is the driving ethos behinds these silhouettes. With such little structure inside to anchor them down, these coats flutter and sway when moving, as though they were waves rippling through water. Even when the wearer is standing still, something about the way the fabric falls across the chest and down the arms suggests motion. George believes this reflects an Eastern philosophical mindset (“a desire to go with the flow”) and fits China’s taste for tailoring. “If you opened a tailoring shop in New York City, you might expect a certain kind of clientele, such as finance workers. In that case, you know the dress code. But in China, we don’t have this Western tailoring DNA. Some people are required to wear a suit, but most of our customers don’t. They might wear streetwear one day and a tailored suit the next day. There’s no preconception of how one should dress for work. So it’s rare for us to get someone who wants a whole wardrobe of just navy suits. They want something that fills a niche in their wardrobe and feels special. In this sense, we’re not just selling a tailored jacket; we’re selling a personalized item.”

As the tailoring trend in the last twenty years has favored shorter and slimmer fits, these coats are their stylistic opposite. There’s a generous amount of fabric everywhere — across the shoulders, around the chest, and down the back. The lapel almost blooms out of the jacket’s bottom-most buttonhole, going up through the buttoning point and to the jacket’s gorge (most lapels break at the buttoning point or even slightly above). Yet, the coats don’t look messy; they look intentional. The fabric has been shaped in such a way to give the coats a strong silhouette. “We took a lot of pattern-making methods from workwear, specifically in the way the shoulders are constructed and sleeves set, which allows for freer movement,” George says. “The idea is to create something that really moves with the body.”

Over the course of our conversation, I was surprised to learn that there are some limits to personalization. BRIO Pechino’s tailoring program essentially allows you to choose three things: the type of garment (e.g., suit or sport coat, single- or double-breasted), the fabric (which George will help you select based on a conversation about your needs and lifestyle), and your method of payment. Details such as vents, pleats, pocket styles, and the number of buttons are non-negotiable.

This not only runs counter to most bespoke tailoring houses but indeed the general clothing market. At a time when companies are clamoring to allow customers to customize an ever-increasing number of details, often with high-tech interfaces that enable them to visualize their choices in real time, it seems odd to have a bespoke tailoring program that limits one’s choices. But George doesn’t want to compromise his house style and feels certain obsessions are missing the point. “It’s a bit like what’s happened with cars,” he says. “Nowadays, cars have to have all these features because that’s what you ‘have to have.’ But none of those features improve the car’s performance. The same has happened with clothing. What does a monogram achieve in terms of style, and aren’t we all here for style? We should discuss the important things.”

Sometime in the near future, George wants to create a campaign showcasing how certain well-dressed Chinese men have worn Western clothes, such as the masterful architect I.M. Pei and celebrated modernist Sanyu. “If you look at Chinese men from the past, especially those who spent time in Europe, they wore Western clothes, but they didn’t look like Italians or Englishmen. They still look very Chinese. There’s a certain softness in the way they wore their clothes. That’s the feeling I want to evoke with our house style. It’s rooted in classic Western tailoring, but there’s an Eastern take on it. It removes some of the sharpness from this traditionally very masculine style of clothing.”

George also feels that representation matters for his customers. As a brick-and-mortar store, nearly all of his customers will be local Beijingers, usually Chinese. “If you look at historically well-dressed Chinese men, they’re stylish because it’s their personality that stands out, not their clothes. I don’t want customers coming in thinking that we can make them look like Lino Ieluzzi, Luca Rubinacci, or any other men’s style figure. I want them to have different style heroes. If it’s someone with an Asian face, it’ll be easier to forget the face and focus on the ‘how’ and ‘why.’ If you’re looking at Luca, you can never forget the face, and you’re just focused on the ‘what’ — ‘what is he wearing?’ and ‘how can I get that too?’ Hopefully, by putting forward other style figures, people will think more about why they’re choosing something and how they’re putting things together. Then they can personalize things and make a style of their own.”

(Readers can follow Atelier BRIO Pechino on Instagram. At the moment, there are no plans for a webstore, but if you see something you like, you can message the shop on Instagram to place an order.)