In the storybook tale of how clothing is made, there are three tiers of production, each ascending a luxury pyramid. At the bottom-most level, you have ready-to-wear, which are those clothes we see hanging on racks and in stores, ready to be tried on, coveted, and perhaps even purchased. The next level up is made-to-measure, where a block pattern is adjusted using a client’s measurements, and then, we assume, a whizzing, thumping machine somewhere shoots out a custom-tailored garment. Finally, at the capstone of this pyramid, there’s bespoke, the highest expression of craft. In the popular imagination, bespoke is about the hush-hush, wood paneled rooms on Savile Row, where tailors work diligently around ancient tables stacked high with heavy bolts of worsteds, flannels, and tweeds. For many, bespoke is “the dream.”

That’s the story anyway. Men who are just getting into tailored clothing often think they should climb as high up on this pyramid as their wallet allows. But in reality, clothing production systems are much more complicated, and there are good and bad examples of clothes in each tier — quality ready-to-wear, bad bespoke, and everything in between. Rather than being stacked on a pyramid, these systems overlap with each other in meaningful ways. To understand how clothing is made, we have to go back to the early 19th century, when the development of the ready-to-wear industry coincided with the industrial revolution, the emergence of modernism, and the American Civil War.

There was a time when nearly all men wore bespoke clothes. Before the Civil War, most men had their clothes custom made by a tailor, if they could afford one, or by women in their home. The only ready-made clothing at this time was crudely sewn workwear, often produced for sailors, miners, and slaves. It wasn’t until 1849 that Brooks Brothers debuted the first ready-made suit in meaningful quantities, and even then, the quality of these clothes paled when compared to bespoke garments.

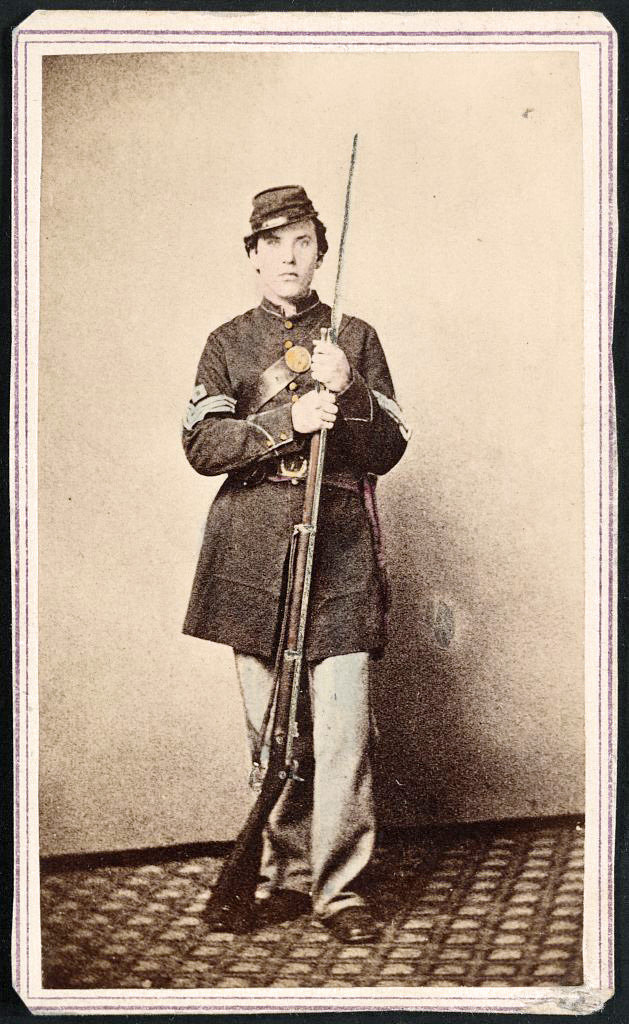

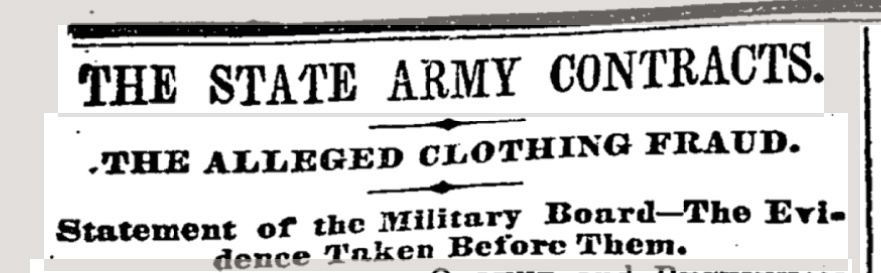

There’s a story that neatly illustrates some of the challenges of the ready-to-wear industry at this time. When the simmering tensions between the Northern and Southern states boiled over into what would become America’s bloodiest conflict, the US government found itself suddenly needing to clothe a vast Union Army. So in 1861, the US Quartermaster Department awarded Brooks Brothers a contract to fabricate some 36,000 uniforms. Each uniform was to consist of an overcoat, a jacket, and a pair of trousers, to be paid at a rate of $19.50, making the contract worth a total of about $170 million in today’s dollars.

The results were a disaster. Brooks Brothers’ uniforms were ill-fitting and poorly sewn, and they arrived at Union camps missing pockets, buttons, and buttonholes. The government initially asked for these clothes to be made from an “Army cloth,” but was negotiated down to an “equivalent cloth” for cost purposes. Facing a scarcity of wool, Brooks Brothers took it upon themselves to manufacture their own “woolen” by smushing together decaying rags, sawdust, and glue. Rather than protecting soldiers from inclement weather, these uniforms scattered into the wind as rags and dissolved into “their primitive elements of dust under the pelting rain.” Worse still, since some uniforms were delivered in non-regulation colors, confused Union soldiers sometimes shot at each other on the battlefield.

In the 1960s, Brooks Brothers was known as the quiet, dignified clothier of American professionals, but a hundred years earlier, they made headlines as a war profiteer. Brooks Brothers’ uniforms soon became the target of jokes in newspapers, magazines, and songs. While marching off to battle, some Union officers sang:

Shoddy ripping, shoddy bursting,

Shoddy rotting in a day;

Coats with holes without the buttons,

Half of blue, and half of grey;

Coats too large and costs too little, —

Coats not fitting any body;

Jackets, overcoats, and trowsers,

Made of cheap and shameful shoddy;

Regiments of gallant fellows,

In a pauper garb bedecked;

Ripping seams and jackets ripping,

Pantaloons completely wrecked;

Who then blunder’d? Who then swindled?

Let us print his blasted name!

Let us hang the suit of Shoddy,

On his own dishonor’d frame!

Lexicographer James Murray, who served as the primary editor of the Oxford English Dictionary from 1879 until his death, claimed that Brooks Brothers and other wartime manufactures were responsible for bringing the term “shoddy” into American usage. A Harper’s Weekly journalist of the day described the term as meaning “a villainous compound, the refuse stuff and sweepings of the shop, pounded, rolled, glued, and smoothed to the external form and gloss of cloth.” Shoddy soon came to mean the cheap and nasty. In his 1863 novel The Days of Shoddy, Union Army veteran Henry Morford took things a step further by using the term as a synonym for the “miserable presence of patriotism — a shadow without substance.”

To be sure, there was something shoddy about Brooks Brothers’ operation, but not all their failures were entirely their fault. At the time, the ready-to-wear industry was still trying to figure out how to make standardized sizes that would fit a broad range of people. Lacking capacity and quality controls, it was also quickly overwhelmed by the sheer volume of orders, to be delivered at the turnaround times requested. It would take another few decades to transform the homespun into its ostensible, ready-made opposite. As Michael Zakim wrote in his brilliant book Ready-Made Democracy, the reorganization of labor, the rationalization of production, and the one-price system eventually gave birth to the clothing industry, and later, democratic capitalism.

Today’s ready-to-wear industry is a far cry from those Civil War years. The tailor’s role in the early 19th century has been since split into various professions — the designer, pattern maker, paper cutter, etc. The fragmented and globalized supply chain has also allowed niche industries to specialize in tiny parts of the production process, such as dye houses that only do garment dyeing, spinners who only spin yarns, and trim suppliers who only make canvassing and zippers. In the 1950s, the fusible also transformed the tailoring industry, making tailored clothing more affordable to all. Today, the clothing industry is so advanced that Zara can bring something from the design stage to the sales floor in just fifteen days, and deliver over 30,000 new units a year to nearly 1,600 stores. Ready-made doesn’t necessarily mean cheap and nasty, either. At 100 Hands and G. Inglese, you can find finely sewn dress shirts with a level of handwork that far surpasses what you can get from most bespoke tailors.

The difference between ready-made and bespoke is simply in pattern drafting. Ready-made clothes are produced using a broader set of measurements, often averages of different bodies within a category. By contrast, bespoke is about making one garment to fit one person (sometimes successfully; sometimes not). Somewhere between these two worlds is made-to-measure. Once dismissed as the worst of both options — the inability to put things back on the rack if you don’t like it, but not the precision of tailor-made clothes — made-to-measure has been rapidly developing in interesting ways.

Historically, made-to-measure has been limited by its block patterns. A company will develop a standard pattern based on an idealized body type and a “house style” — slim modern, soft Continental, structured power suit, traditional American, and so forth. If a client’s body doesn’t fall within a specific range of this block pattern, the system breaks down. This is the paradox of made-to-measure. Ostensibly, it should be for people with atypical builds, but to turn a profit, made-to-measure companies often have to cater to more average-sized people.

In the last few years, however, technologists and tailors have been working together to develop a new system that may one day allow machines to draft patterns from scratch. Traditional drafting systems typically rely on calculations based on a person’s proportions. In this new algorithmic, if/then system, a machine will draft a pattern based on a set of conditions, much like a tailor. Jeffery Diduch, the Vice President of Technical Design at Hickey Freeman, has been working on such a system with a new company called Tailored. “In other words, if the difference between the stomach and chest is less than seven inches, then you’re doing one set of calculations,” he explains. “If it’s more than seven inches, then you’re doing another set of calculations. It’s all conditional, which allows us to create a custom pattern from scratch.” The company is currently gathering data of atypical builds — crooked figures, bodybuilders, and those outliers who have trouble finding clothes off-the-rack. The system is still in its infant stage, but early results are impressive.

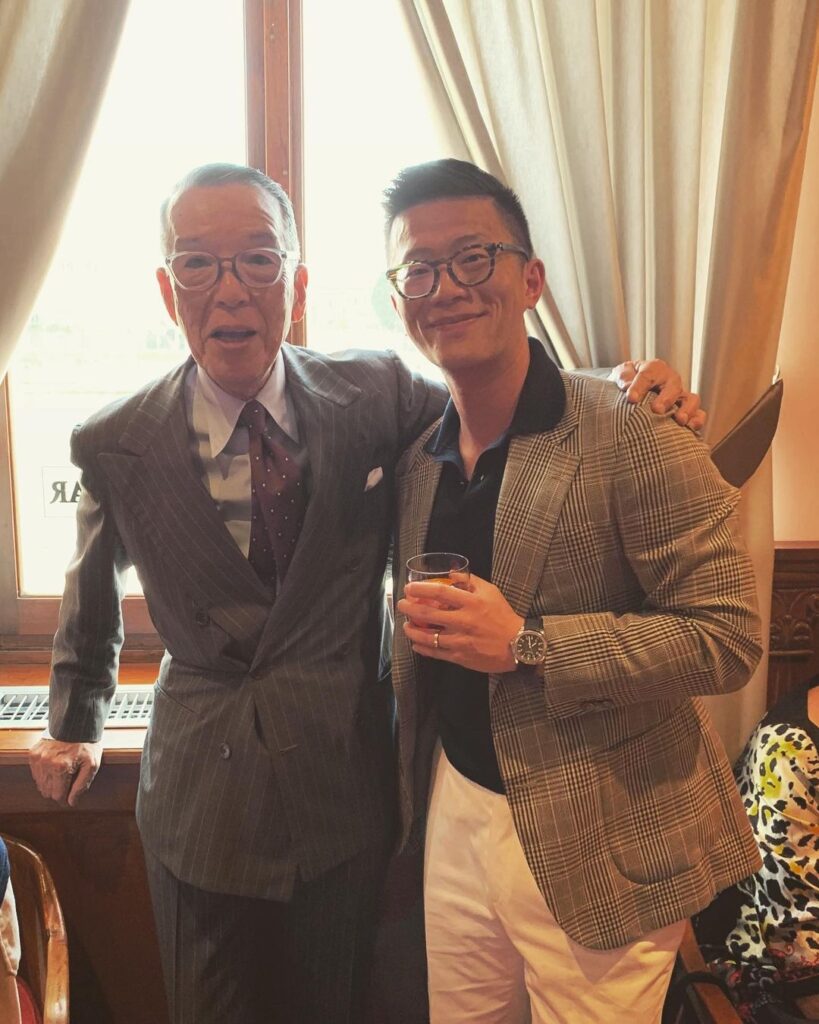

There’s yet another development on the craft side of the business. A few years ago, I was sitting at a cafe with BRIO founder George Wang, who was telling me about a new made-to-measure service he had recently set up with one of his bespoke trunk show partners, Sartoria Dalcuore. In this system, a fitter puts a client into a sample garment and then takes notes of what changes need to be made to the standard pattern. Those notes are then sent to Dalcuore’s workshop in Naples, Italy, where the garment is made straight to finish and then sent to BRIO. At a subsequent meeting, the client has his final fitting, and any small changes that need to be made — such as a nipping of the waist or adjustment of the sleeves — are done locally by BRIO’s in-house tailor.

We often hear that bespoke is about having a tailor draft your pattern from scratch, and then refining a garment through a series of three fittings. Made to measure, by contrast, is about having a technician adjust your pattern from a block, often using a computer-aided design program, and then only having a single fitting. But such descriptions don’t fully capture reality. On Savile Row today, you can find many tailoring houses using labor-saving devices such as block patterns, although they adjust theirs by hand. At Anderson & Sheppard, tailors will also skip the basted fitting and go straight to the forward (making it a two-fitting process). If a made-to-measure company adjusts a block pattern by hand and puts a client into a sample garment first, the line between bespoke and made-to-measure starts to blur. When done at these small, bespoke workshops, I call this sort of system “benchmade to measure,” as the only thing you’re losing is the extra fitting for that marginal improvement.

“I actually prefer this over bespoke, provided there’s a local tailor who can fix any glaring issues,” says George. “If you don’t have a local tailor who can give things a final look, then you have to be careful about communicating what you want to change from the standard pattern. This requires extensive experience in working with a particular tailor. This type of service is cheaper, usually by 30% or more, and it gets you 90% of the look and feel of bespoke, so the value is there. All things being equal, of course, as quality in this field varies. More and more, I feel that a good pattern is more important than a good cutter. So many talented English tailors cut ugly jackets because their base pattern is so horrible. If you get the base pattern right, most of your customers won’t even need to go bespoke. I have things that were made straight to finish, and they fit better than some of the things where I’ve had four or five fittings.”

Herrie Son and Kyle Komline, the couple behind the bespoke tailoring shop Herrie in Nashville, set up a similar program as an alternative to their bespoke service. In their bespoke program, Herrie cuts all of the garments in Nashville and then has the pieces sent to Italy for making. This system goes back and forth between fittings until the garment is shipped for final delivery. But through the made-to-measure process, the client tries on a sample garment in Nashville, and then Herrie takes notes of the changes that need to be made. Since she’s an actual cutter, she can make in-depth, technical notes on a line drawing of the pattern. The production process then happens in Italy, and the final fitting is done in Nashville.

Since this system requires fewer fittings than bespoke, Herrie can offer a two-piece, machine-made suit for just $1,900 (excluding the price of cloth), which is a thousand dollars less than her starting price for a handmade, two-piece bespoke suit. Kyle notes that the margins are slim for MTM, and the company only really turns a profit if a customer comes back for a second order. “The hard part is managing expectations,” he says. “With bespoke, both you and the client can see how the garment is coming along at iterative fittings, so there are no surprises. With made-to-measure, things are produced straight to finish. Even if a client tries on a sample garment, they may have difficulty visualizing how the changes will look in the end. So if the final garment comes and fits perfectly, but the customer is unsatisfied in ways they can’t express, what can you do? We want the person to be happy, so sometimes we’ll do a bunch of alterations and end up losing money. We still haven’t figured out that part.”

Jack Liang, the founder of Trunk Tailors in Australia, offers an even more aggressively priced made-to-measure service. For a fully handmade suit, prices start at just $1,200; sport coats begin at $800 (in our interview, I was so surprised, I asked him to clarify twice. “That’s the market here,” he said). The garments are made in Hong Kong, not Italy. Still, they’re built to impressive standards — the chest padding, collar attachment, sleeve attachment, buttonholes, and edge stitching are all executed by hand. The company also offers an extra fitting service for just $250.

“Since our prices are so competitive, it’s easier for guys to experiment with different styles,” he says. “Still, I find that it’s better to sell people on the fit and feel of the finished garment, not the handwork. Most guys don’t care about handmade buttonholes; if you spend 45 minutes showing them how the buttonholes look three-dimensional, they’ll think all their money is going into a detail they don’t care about. So you want to win them over on the fit and feel of the final garment. When you cut a high armhole, they can feel how the jacket gives them more mobility. When you cut a higher rise, they can see how there’s no visual gap when they fasten the jacket. When they sit down, they can feel the comfort of that single pleat. The suit should naturally feel better than what they’ve experienced off-the-rack. That’s how you get them to come back.”

Many of Trunk’s clothes have a modern, Italian flavor, but they still feel rooted in classic sensibilities. I appreciate that the company is bringing a new generation of men into classic, custom tailored clothing, at a style they prefer, in silhouettes that will endure, and at a price point they can afford (crucial in this market). Like with other business owners, Liang says the challenge is managing time and expectations. “You have to be upfront with clients. Sometimes a guy will come in because he knows we use a workshop and not a factory. So he’ll give me a photo of a Liverano suit he saw online, which he wants to be copied. You have to be very careful with this sort of thing. First, this sort of copying cheapens your business. Second, so much goes into a garment; it’s not as easy as just copying and pasting the silhouette. Third, if you say you’re going to deliver this thing, they will always use that photo as a basis for comparison. It sets you up for failure, even if you’ve delivered a beautiful product.”

On this point, everyone interviewed agreed that there’s something special, perhaps even untouchable, about bespoke (at least when it’s done well). Herrie says that handsewn seams have a certain “bounciness” and “life” to them, whereas machine-sewn seams often look flatter. Bespoke garments are also typically made with more generous inlays, which allows for greater flexibility when altering the garment over the course of its lifetime. “A lot has been written about how a jacket fits to the body, but almost nothing has been written about the parts of the jacket that fit away from the body, the parts that don’t touch the body at all,” adds George. “These areas are the sexiest, the part where ‘style’ is formed. I’m talking about the swelling of the chest, the extension of the shoulders, the flaring out of the skirt or quarters. These are the things tailors think about when they do bespoke fittings. In made-to-measure, these parts are fixed, and the tailor is only working on fit issues, sort of like problem-solving.”

Still, the future of clothing production may lay with made-to-measure, especially if MTM companies can overcome their early challenges like the ready-to-wear industry. If technologists can develop machines that can draft patterns from scratch, made-to-measure tailoring will be more precise, especially for atypical builds. Additionally, if small bespoke workshops can offer some sort of “benchmade-to-measure” service, they can provide customers with a taste of bespoke at a fraction of the cost. “Whatever the justifications were for made-to-measure in the past, it may be the only way forward in a pandemic world,” says George. “Without the ability to travel, tailors can’t easily see customers, so they have to develop some MTM service, or they’ll cease to exist. Luckily, I think the market was already trending towards MTM before the pandemic, so most outfits are ready. The bigger challenge is the trend away from wearing tailoring.”