In 1994, advertising executive Donald Rifkin came up with a new installment for Coca-Cola’s “Obey Your Thirst” campaign, designed to promote the company’s sparkling lemon-lime beverage Sprite. In the commercial, a young white teen with an unfortunate center-part haircut wrestles with one of life’s eternal questions: “what is cool?” As he stands at a city intersection, our narrator considers the various identities he can adopt to boost his social standing — hip hop head, defiant skater, or entitled prep (“now that is not cool,” he quickly surmises of the third). By the end of the 30-second advert, he still has not chosen an identity, but Coca Cola assures us that he can at least give his mind a rest by selecting the one reliably cool drink, Sprite.

When this commercial aired, countless corporations were already clamoring to co-opt street culture as a way to gain street credibility and reach new markets. In the decade prior, companies such as Philips, Atari, McDonald’s, Hershey’s, and Mountain Dew aired hip hop themed advertisements, which featured breakdancers popping and locking to sell everything from egg sandwiches to chiropractic services. Following the success of Jane Fonda’s at-home workout videos, many companies also tried selling breakdancing videos to teach people how they can top rock, windmill, flare, float, and freeze. By the mid-90s, breakdancing was so thoroughly co-opted by the Suits, it was considered uncool in the streets, and a new dance movement emerged called freestyling.

It was also around this time when streetwear became legitimized as a fashion market. To be sure, street and youth culture have long existed. Since the end of the Second World War, young people in Britain and the United States have expressed themselves as beats, beatniks, bobby soxers, modernists, mods, hippies, bohemians, surfers, skaters, punks, and rockers. During mid-1940s Britain, ex-Guards officers, many of them gay, ordered fanciful Edwardian suits from their Savile Row tailors as a reaction to demob dreariness. These suits were defined by their long, flared skirt, turnback cuffs, and tight, drainpipe trousers. At the time, this New Edwardian style was fashionable in posh gay circles, having been championed by society photographer Cecil Beaton and the dandy couturier Bunny Roger. Savile Row tailors were all too happy to promote the look, as doing so helped fill their ledgers with orders.

Within a decade, however, the cash tills in lower-end London shops were ringing, as young men from the traditionally working-class areas of London — Hackney, Tottenham, Shepherd’s Bush, and Elephant and Castle among them — bought cheaper New Edwardian imitations to emulate their heroes in B-movie Westerns, such as frock-coated gamblers who sauntered into saloons. These wide-boys and spivs, as they were called, bought their suits using the money they earned from wheeling and dealing on the black market. Of course, respectable elites and traditional Savile Row tailors wanted nothing to do with this teen menace, so they dropped the New Edwardian style entirely, leaving the look to the working class. This was the emergence of Britain’s first rock rebels, known as the Teddy Boys and Girls. “The reason why you have to love those original Teddy Boys is because [they were engaged in] a wonderful act of class rebellion,” Robert Elms, author of The Way We Wore, said in the BBC documentary series British Style Genius. “These working-class kids were quite literally nicking the style of their betters, and that really upset the establishment, who called them Little Caesars.”

As a term, streetwear today refers to distinctive fashions derived from post-1970s urban life. This can include anything from hip hop to basketball, punk music to skateboarding, and even a bit of illegal drug culture. If fashion folklore is to be believed, Carhartt’s russet brown chore coats and Timberland’s wheat-colored work boots first made it off the worksite in the 1980s when inner-city drug dealers started wearing them as their inconspicuous and durable cold-weather garb. “The grit of criminal life necessitated affordable outerwear, and Carhartt’s work jacket offered a certain anonymity,” Gary Warnett, a contributor to The Carhartt WIP Archives, once explained in a Racked article. As Carhartt and Timberland became symbols of street culture, rappers immortalized them through their songs and wore them in their music videos. This broadened their appeal to wealthy suburbanites who yearned to be associated with street cool. “I think when kids want to be associated with certain brands, they first have to see it on someone they value,” says Daymond John, founder of FUBU.

There’s a tragic irony in this. Today, Carhartt work jackets and watch caps aren’t just worn by construction workers, inner-city drug dealers, or even people involved in street culture. Instead, you can see them in upscale cafes and art galleries in some of the most gentrified areas of the United States. The same people who co-opt symbols of edgy street culture will often lobby for stricter and more punitive policing measures to stamp out the very urban communities that gave such symbols their credibility.

In sociology, this is referred to as “postindustrial policing.” The term postindustrial here refers to the set of developmental strategies many cities have adopted in an effort to revitalize their economy. After sequential waves of deindustrialization, cities that aspire to global city status often aim to develop within their borders knowledge-intensive service sectors, such as finance, media, education, engineering, and the arts. To attract highly educated and creative workers, city officials will build the kind of cultural amenities, shopping districts, and tourism sites that serve such people. Richard Florida, a noted urban theorist who has written much on talent migration, refers to these groups of “high bohemians” as the “creative class.”

At the same time, members of the creative class often have a low tolerance for petty offenses (such as panhandling, public intoxication, and public disorder) and the presence of physical disorder (such as an unfixed broken window). They see such offenses as a breakdown in the social order. Consequently, they lobby for heightened policing to purge targeted areas of the city of the individuals and behaviors they associate with crime and urban decay. In practice, this means that the police often target specific people, such as the young, the homeless, and people of color.

In his 2018 Urban Affairs Review essay, titled “Coffee Shops and Street Stops,” political science professor Ayobami Laniyonu not only found evidence of a linkage between gentrification and over-policing, but also the spatial relationship of such efforts. “Gentrification in a tract does not necessarily induce heightened policing in the tract that experienced it, but significant policing in adjacent or neighboring tracts,” he writes. “These results are consistent with [Mike] Davis’s analysis of revitalization and policing in Los Angeles, in which the homeless in that city’s downtown central business district were pushed to Skid Row, where their rates of contact with police officers subsequently skyrocketed. […] Gentrifying in-movers likely do not prefer to see heavy and frequent policing in their neighborhoods any more than they prefer to see signs of ‘disorder,’ as it sends negative signals about their neighborhoods, specifically about crime.”

The people who purchase the upscale symbols of street culture are often not very tolerant of actual street culture. On Mr. Porter, you can find $700 designer skateboards decorated with Keith Haring’s graffiti art, $40 Carhartt WIP x Wacko Maria watch caps, and $2,075 psychedelic cashmere sweaters that look like they belong in a head shop. Such are the things you’ll see in homes and on the streets in historically cosmopolitan areas such as Brooklyn, East Los Angeles, and San Francisco. Yet, these districts are also a shell of their former selves. In the ’90s, San Francisco was rich with an organic street culture that revolved around skateboarding, graffiti, and underground music. But in the New Economy, noise ordinances, petty policing, anti-skateboarding architecture (which often doubles as anti-homeless architecture), and skyrocketing rents have pushed skaters, artists, and musicians out of the city. In urban areas across America, genuine street culture has been replaced by its symbols — the Carhartt watch caps in cortado-selling cafes and designer skateboards hung inside expensive two-bedroom apartments.

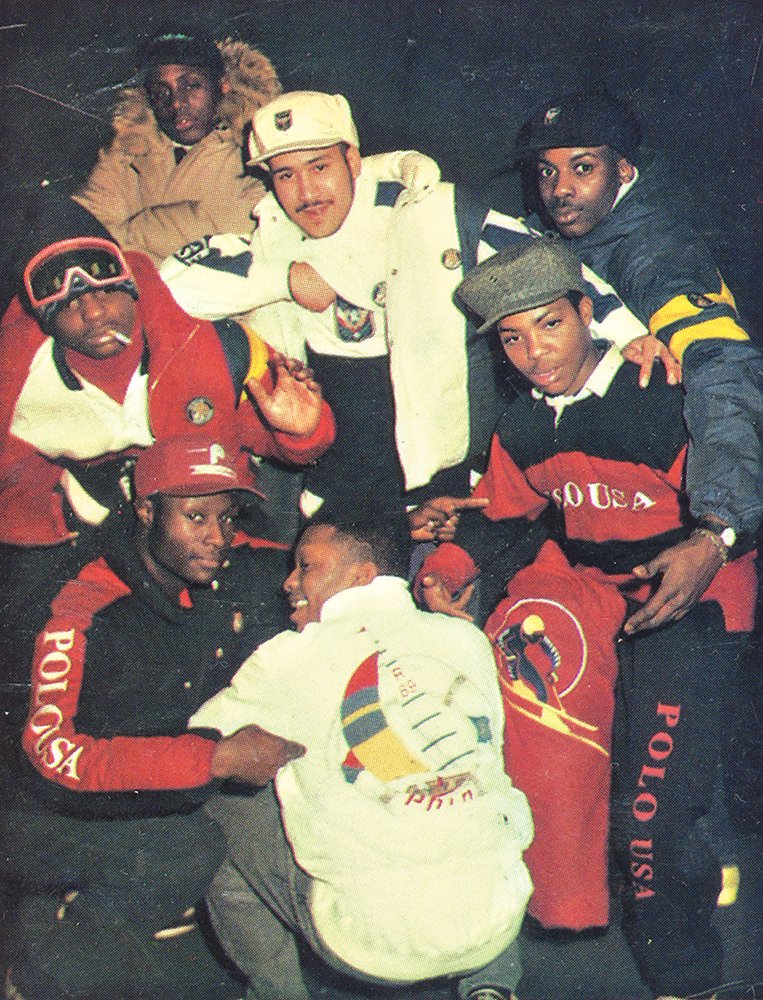

My first introduction to fashion was through streetwear. In the 1990s, friends of mine were ‘Lo Heads, who are called so because of their obsession with Polo Ralph Lauren. Many of these people were involved in the bourgeoning freestyle dance scene, which grew out of underground dance clubs such as New York City’s Latin Quarters (the 1992 PBS documentary Wreckin’ Shop follows one of New York City’s most famous dance crews, The Mop Tops). Dancers showed up in dimly lit venues wearing the most colorful Ralph Lauren garb you can imagine. This included choice pieces from the P-Wing and Stadium collections, the famous Indian Head sweater, and the ’92 Ski jacket (also known as the suicide ski jacket because wearing it outside was like committing an act of suicide given the high probability of you getting robbed).

Like the Teddy Boys and Girls before them, ‘Lo Heads were engaged in rebellious acts of class appropriation, nicking the symbols of success from their supposed social betters. This community was mostly made up of Black and Latino men who wore WASPy clothes. However, they didn’t in any way aspire to be like rich, white preps. Instead, they took the clothes and made a style all their own. Polo collectors like things with the graphic and textual representations of certain class ideals, such as golfers, skiers, and the iconic Polo Bear wearing a tuxedo. They like color blocking and intensely bright color schemes. Their outfits have bravado.

The important thing is that this style was organic, democratically determined by people on the street, not the Suits in boardrooms. In fact, the Suits didn’t understand the logic behind which things were popular, as these outfits were being put together using a whole new language. In the 2018 documentary Horse Power, Sean Jean CEO Jeffrey Tweedy reminisces about his time working at Ralph Lauren. “We used to get calls from major department stores and specialty stores about how things were being stolen,” he says. “In the world of wholesale and resale, it’s called shortages. And shortages showed up on your computer report that you had 100 pieces one day, and the next day, 80 were left. So someone stole 20 pieces. And people learned that [‘Lo Heads] stole the rugbys, but not the sweaters. People don’t steal stuff that’s not good. So they started designing more of those things. That’s why I say the culture influenced Ralph’s company.”

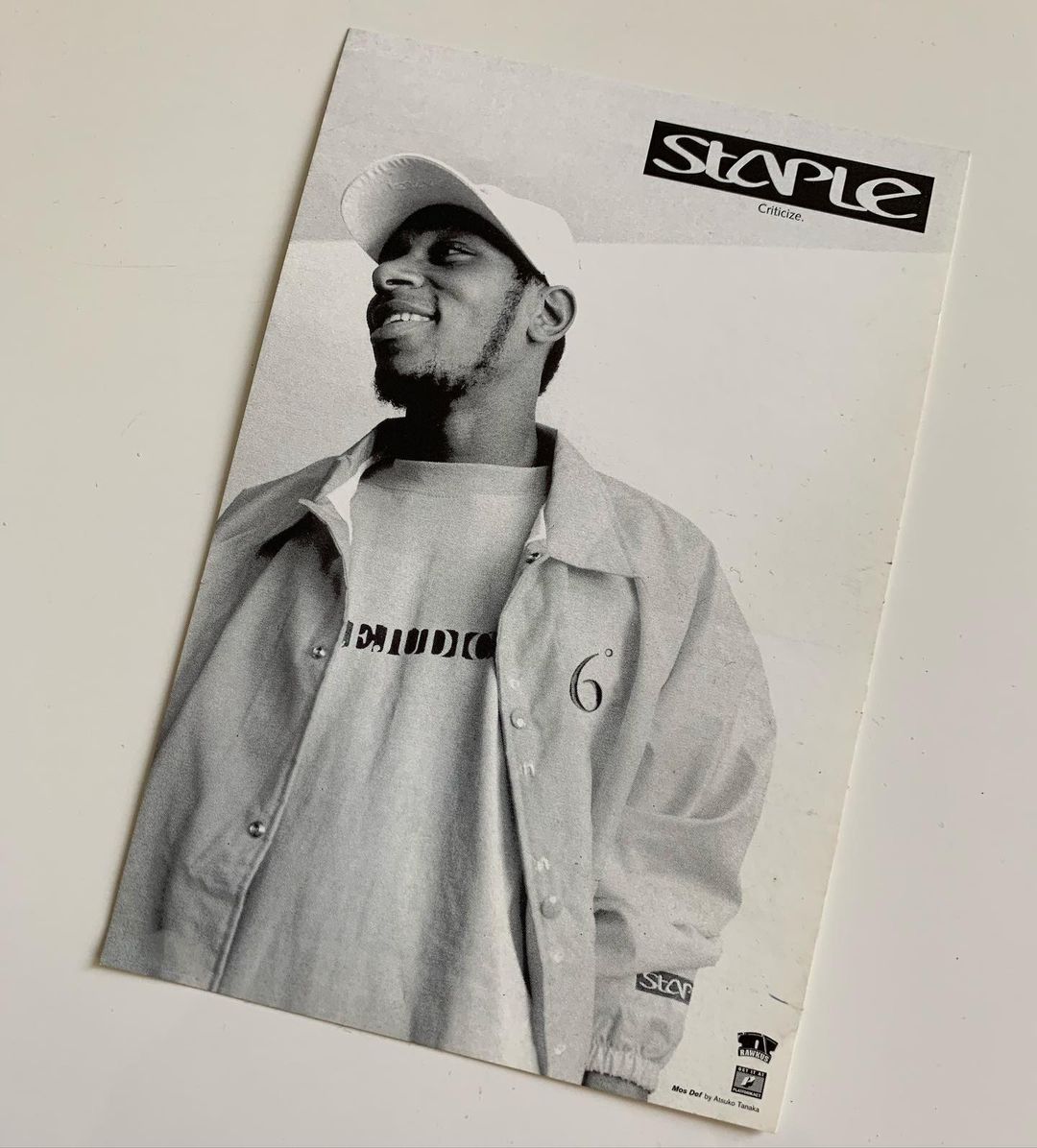

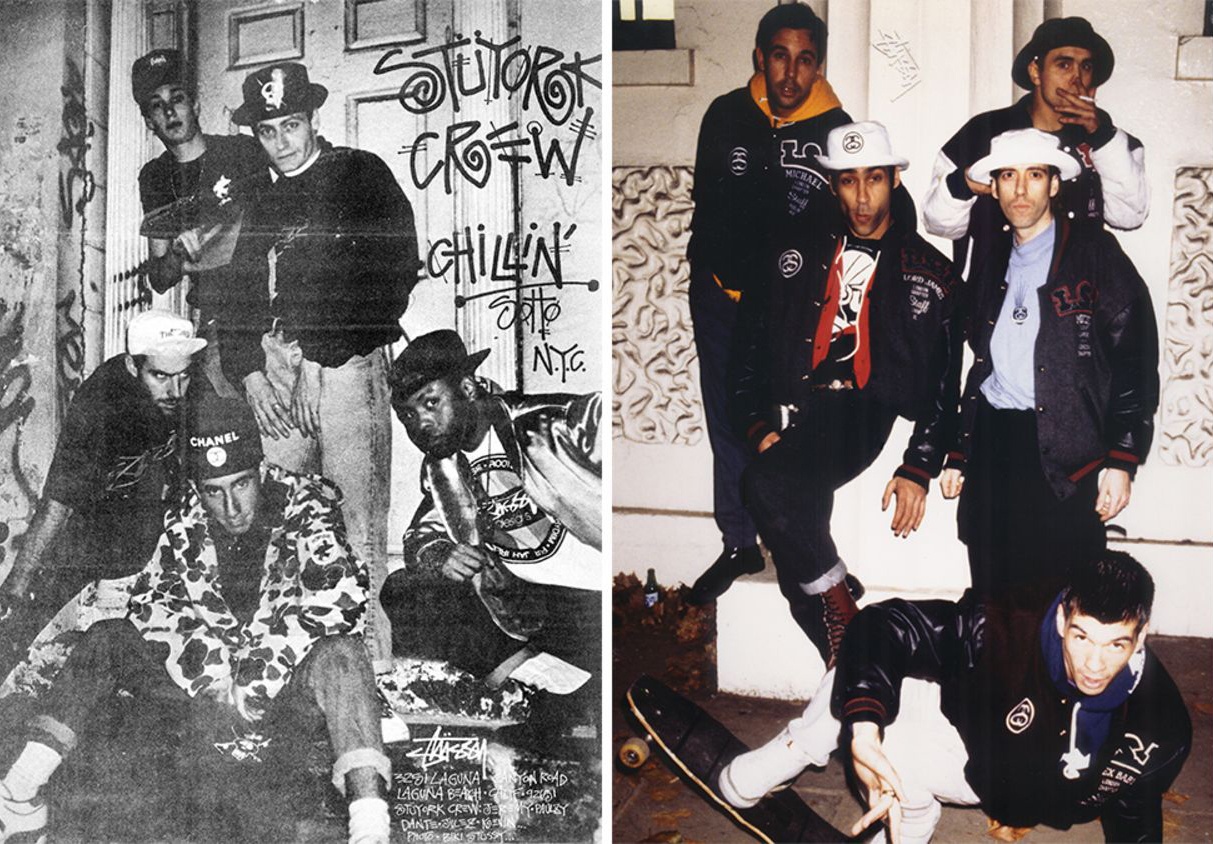

Something changed in the 1980s and ’90s. Instead of running away from street culture, like those Savile Row tailors who dropped the New Edwardian look, many companies started to embrace it — sometimes even chase it. The first big streetwear labels sprung out of actual street culture. Shawn Stussy was a surfer who sold handcrafted surfboards, t-shirts, shorts, and caps out of his car in Laguna Beach, California. Ash Hudson and Marc Ecko were actual graffiti artists before starting their graffiti-inspired clothing labels, Con Art and Ecko. The people behind Triple Five Soul, Staple, and PNB Nation could often be found hanging out at the offices of Rawkus Records, as they were all part of the same tightly knit New York City community. Concurrent with this growth was the emergence of large Black-owned brands, such as Kross Kolors, FUBU, and Phat Farm, which were both about Black culture and hip hop.

As these companies grew and achieved greater successes, larger financial firms and corporations started to take notice. It wasn’t just about the purchasing power of young Blacks and Latinos, but also how these communities set trends for suburbanites. As such, larger and more established brands started partnering with streetwear labels, hoping that some street credibility would rub off on them and allow them to reach new markets. In 1999, LL Cool J appeared in a Gap ad while wearing a FUBU hat, which boosted FUBU’s visibility and gave The Gap some street cred. Yet, among people who were actually involved in street culture, there was always a healthy amount of skepticism of overly popular labels and corporate programming. The Suits were outsiders. This sense of tribalism is well captured in Wu Tang’s “Protect Ya Neck,” where The GZA raps: “First of all, who’s your A&R / A mountain climber who plays an electric guitar? / But he don’t know the meaning of dope / When he’s looking for a suit and tie rap / That’s cleaner than a bar of soap.”

In the last ten years, streetwear has been almost entirely subsumed into high fashion. Nearly every luxury house has an indistinguishable take on the all-white, minimal sneaker aesthetic inspired by Adidas’ Stan Smith. Vetements and Givenchy produce oversized t-shirts featuring Snoop Dogg and great white sharks, similar to the silkscreened tees once hawked at flea markets. At Celine’s spring 2021 fashion show last month, which the company described as a “portrait of a generation,” there was a parade of skinny models wearing oversized boyfriend jackets, white-striped track pants, and chunky elasticated boots similar to Blundstones.

Such is how a lot of streetwear feels today: dictated from the top. Thirty years ago, Stussy and Vans rose to prominence when skaters and punks adopted them as part of their uniform. Polo Ralph Lauren, Nautica, and Tommy Hilfiger got the nod from hip hop obsessives. In the late 1970s, working-class Brits in Liverpool raided golf shops for Pringle’s sweaters and mountaineering stores for Peter Storm’s anoraks. “You had whole crews and gangs of lads wearing Peter Storm almost like a Warriors uniform,” says Jay Montessori, an original casual featured in British Style Genius. “There was no designer driven market back then. Things weren’t made for fashion; things were adopted as fashion. The fashion wasn’t dictated through magazines, the media, or multi-million-pound advertising campaigns. It was designed on the street, for the street.”

The youth still hold a tremendous amount of sway today, but more power has shifted towards brands, corporations, and financiers. Through shrewd marketing and artificial scarcity, designers tell us which things are cool and exactly how to wear them. This is essentially the bet VF Corporation, owner of 19 brands, including Timberland, Vans, and North Face, made earlier this month when they bought Supreme for $2 billion. “Supreme has been flirting with the inside for a while, collaborating promiscuously with companies like Everlast, Louis Vuitton, and Meissen,” Vanessa Friedman wrote of the acquisition. Just eight years ago, Glenn O’Brien described Supreme as a “company that refuses to sell out.” But in 2018, Supreme founder James Jebbia won the CFDA’s Menswear Designer of the Year award, the greatest show of Establishment validation.

A couple of years ago, I interviewed Jason Jules. Some readers may recognize Jason as the face of Drake’s, but he’s also a vet in the London arts scene, having worked as a club promoter, PR rep, and fashion industry consultant. I asked him if there are still youth subcultures that can be identified by the ways they dress. “I think there are, but things move so quickly now, it’s hard to recognize something as peripheral,” he told me. “Palace Skateboards used to be super niche five or six years ago. It was just a group of kids making t-shirts and crazy skateboard videos. Now they’re all over the place, and it’s easy to forget they came out of an incredibly small subculture. Or look at Tyler the Creator and his line, Golf Wang. That originally came out of a subculture and the mainstream didn’t mess with it because they considered the line too obscure, too wild, too odd. Now they’re embraced like latter-day rockstars. It’s just that this transition happens so quickly now, it feels like things can become mainstream almost overnight.”

When I see stylish young people on the street nowadays, they are rarely wearing the kind of Hedi- and Raf-driven fashion people associate with designer streetwear. Instead, they look like they’ve cobbled together their wardrobe through thrift stores and Depop. Perhaps authentic streetwear and its associated street cultures still exist, but I’m too old to know about them. On the fashion side, codified streetwear seems like a game of authenticity. Corporate brands try to appear more authentic by collaborating with niche streetwear labels, and wealthy consumers try to appear more authentic by purchasing those upscale symbols.