When British economist Alfred Marshall was looking out of his window in the late-19th century, he saw a country full of cottage industries and industrial clusters. In the Scottish Border towns up north, thousands of spinners, weavers, and knitters were making robust tweeds and soft cashmere. A little further south was Manchester, where steam-powered mills produced so much of the world’s cotton, the city was known as Cottonopolis. In the East End district of London known as Spitalfields, the descendants of French Protestant refugees and Irish immigrants were toiling over looms to make some of the world’s most beautiful silks. When those silks were woven, they were then transported to Macclesfield, where artisans decorated them with hand-blocked patterns.

Marshall wrote about similar clusters in his book Principles of Economics, which not only became the standard economics textbook in England for decades to come but also sparked an intellectual revolution. Most econ students will know Marshall as the man who transformed economics from the philosophical works of John Stuart Mill and Karl Marx to the rigorous mathematical field it is today. Marshall helped lay the groundwork for neoclassical economics, as well as developed the supply and demand graph. But in Book 4, Chapter 10 of Principles of Economics, there were also a few paragraphs about the benefits of spacial clustering — an idea that would come into greater prominence about a hundred years later and helped to shape developmental policies.

Clustering is the idea that firms benefit from sharing infrastructure, suppliers, and distribution networks. Companies that supply components and support services can fit neatly into each other like Lego bricks. When you have a cluster of businesses, skilled workers can also share knowledge and move between firms, which helps soften the blow of unemployment. Back in the day on Savile Row, tailors across the many firms gathered at the pubs after work, where they would imbibe, gossip, and share ideas. “They were all enormous drinkers,” Thomas Girtin wrote of them in his book Nothing but the Best. “When they had been paid, they would ‘go on the cod,’ indulging in monster drinking bouts — drinking like a fish, perhaps — from which there was no recalling them until they had spent all their money.” Tom Mahon of Redmayne tells me that he remembers how much fun he used to have with other tailors at the pub, as well as how tailors shared knowledge by sketching out drafting patterns on the back of napkins.

Clustering has been used to explain the competitive advantage of certain regional economies. Hollywood is now synonymous with the film industry. In Boston and the Bay Area, partnerships between industry, finance, and academia have driven technological innovation. Just as Seattle is known for aircraft design, we have financial and advertising services in New York City, casinos in Las Vegas, and weirdly enough, a carpet capital in the form of Dalton, Georgia. Today, policymakers often try to figure out how to create and promote regional growth by getting the right “mix” of companies in an area, much like how a baker might combine ingredients to bake a cake.

This idea can also be used to explain how Seoul has become a fashion capital in the last twenty years. In the early aughts, many people would struggle to name a South Korean designer or company. Today, plenty abound. Lie Sang Bong is among the best known overseas, as his lavish clothes have been worn by celebrities such as Beyoncé, Rihanna, and Lady Gaga. Rubina, Yang Hee Deuk, Kwak Hyun Joo, and Park Seung-gun are known for their creative showings. Some of the best bespoke tailoring these days is being done by BnT Tailor. And PARTSPARTs, Document, and Wooyoungmi represent some of the most exciting expressions of minimalism. I imagine many of these designers also benefit from South Korea’s rich heritage in other creative industries, such as music, film, and of course, food. As Richard Florida notes in his book The Rise of the Creative Class, creative people benefit from being near each other.

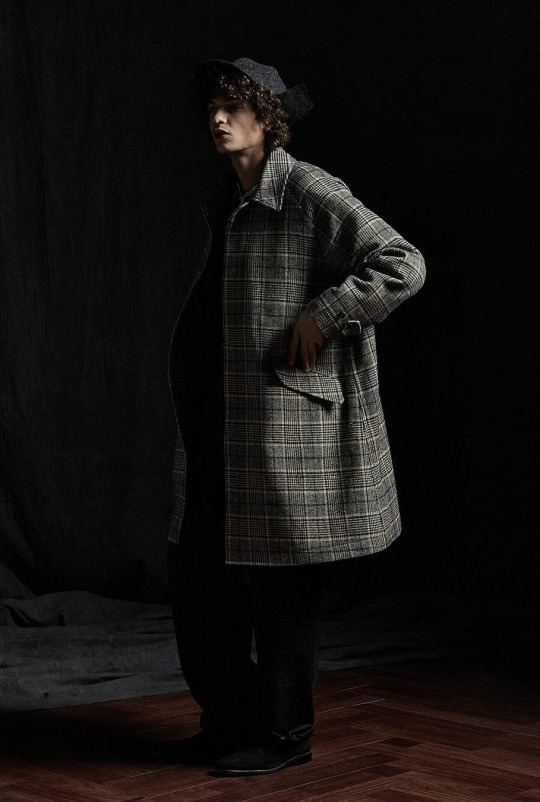

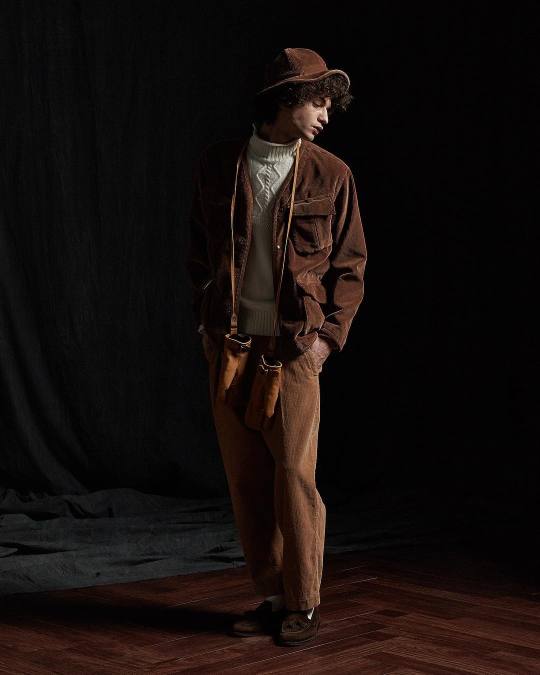

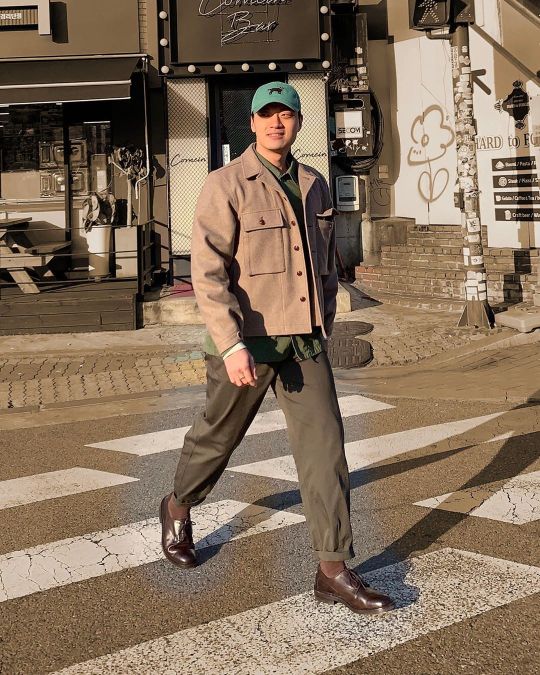

Dong Ki Lee, the talented designer behind Eastlogue (pictured above), thinks a lot of this is due to Seoul Fashion Week. “The Korean fashion scene has really blown up in the last ten years or so,” he says. “Before that, it was dominated by big brands, but things started changing around 2009. Young designers were able to show their work at Seoul Fashion Week, and Korean customers wanted something a bit more unique. I think the demand and supply sides came together well.”

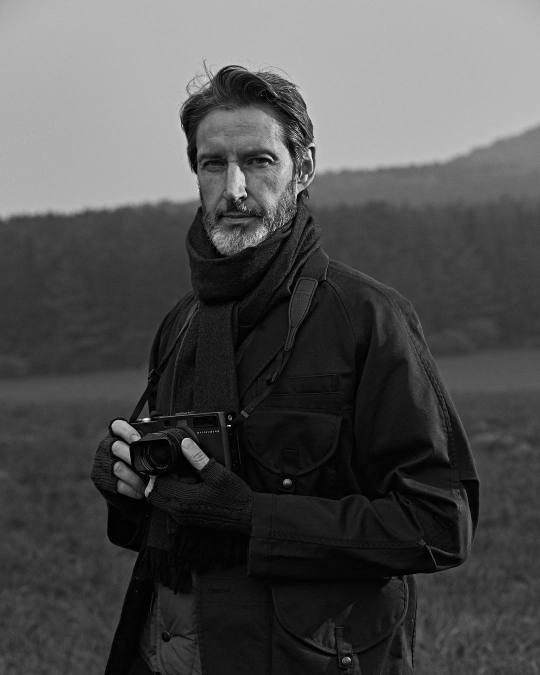

Seoul Fashion Week seems to have been the match that lit the fire. For decades, South Korea has had a strong manufacturing base, a fact that has been well-known to industry insiders who have relied on the country for their production. It wasn’t until the early aughts, however, when there was a growing fashion scene for small designers. It took the government’s support in the form of Seoul Fashion Week, which was part of a bigger program to promote Korean “cultural industries” abroad, to give those designers a center stage. Seoul Fashion Week has helped elevate the visibility of Korean fashion, which in turn has both generated press and sales for small designers and thus support their work. This confluence between art, manufacturing, and commerce has made it possible for a Korean fashion to thrive. Photographer Michael Hurt, who teaches at Hongik University in Seoul, writes at Huffpo:

As a part of what many South Koreans like to now call the “Korean wave,” the fashion industry has not enjoyed the success of other sectors of other so-called ‘cultural industries,’ such as in film, television, and pop music. But this is not for lack of talent within the industry. Rather this lies in the fact that ‘cultural industries’ are simply difficult to promote for promotion’s sake. They usually require a pivotal cultural product to blow up and lead the way. […] [I]nterest in Korean culture doesn’t generally result from interest in Korea itself, but rather the ‘perfect storms’ of interest that pop up around specific people or cultural products.

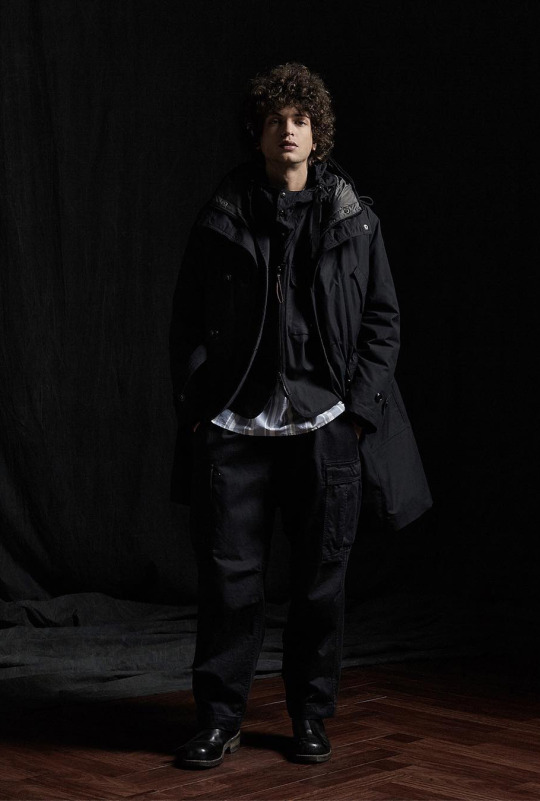

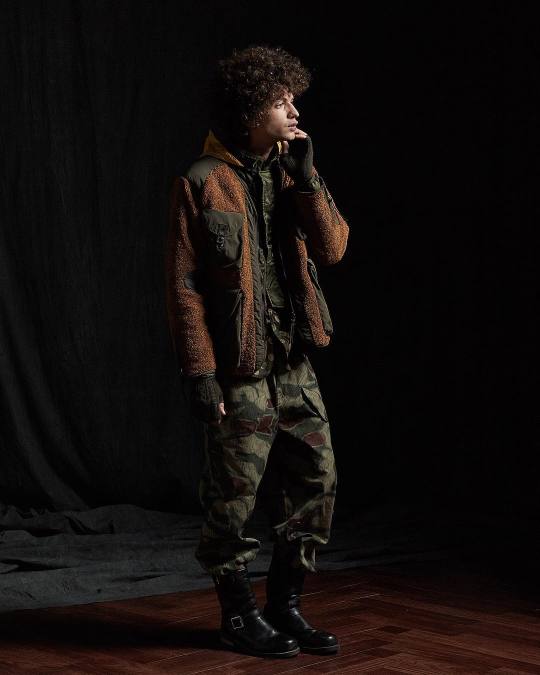

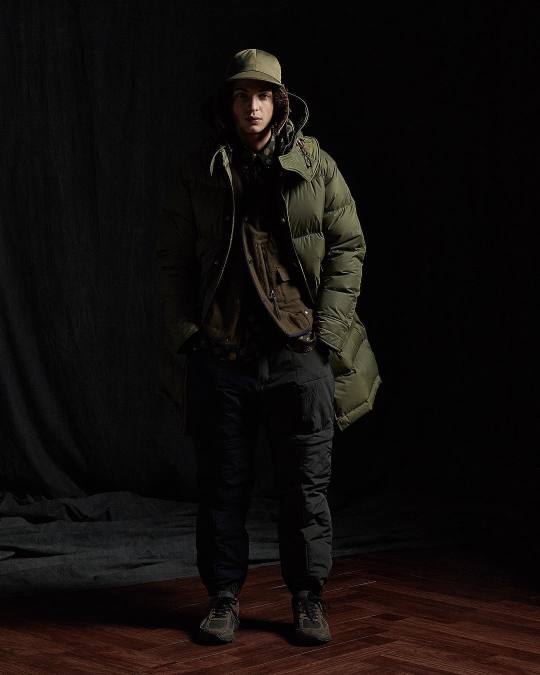

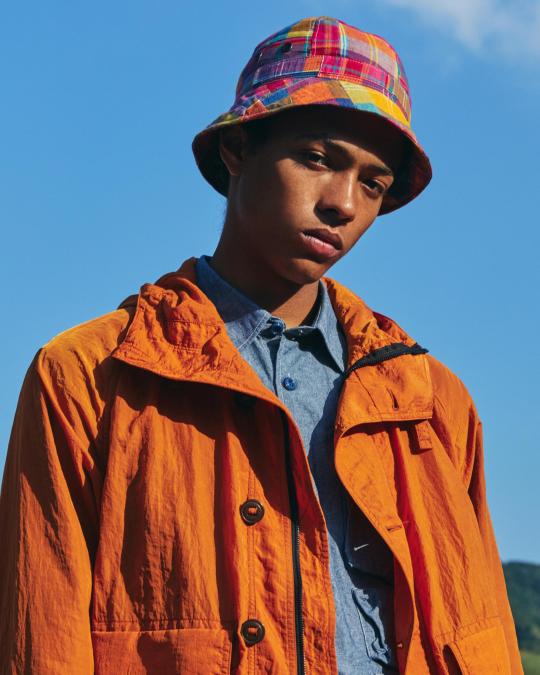

In the past few years, as I’ve paid more attention to Korean fashion, one small label, in particular, has stood out for me. Eastlogue is the Korean counterpart to all of your favorite workwear brands. They make offbeat versions of workwear, military gear, and outdoor apparel. In some ways, such styles are nothing new, but this look has been popular for decades for a reason. The styles are contemporary enough to feel relevant; classic enough to not seem terribly trendy. The clothes have a heavy masculine undertone that makes them easy to wear.

Dong Ki started Eastlogue in 2011 after finishing his university studies in Seattle, returning to South Korea, and completing his military requirements. The name Eastlogue reflects his international interests. The company’s name hinges on that suffix -logue, which denotes discourse or compliment. “I’m keen on American and British sportswear,” Dong Ki explains. “That includes hunting, fishing, hiking, military, and outdoor gear. So, the name Eastlogue means we want to show our interpretation of clothes from around the world while telling a story of our own.”

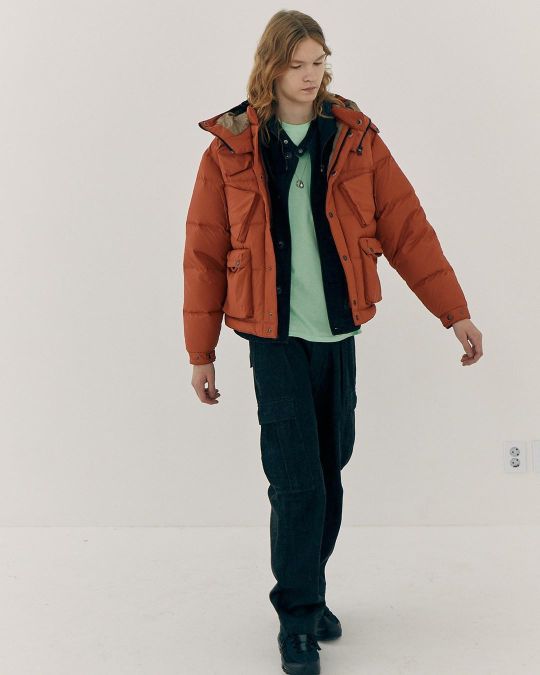

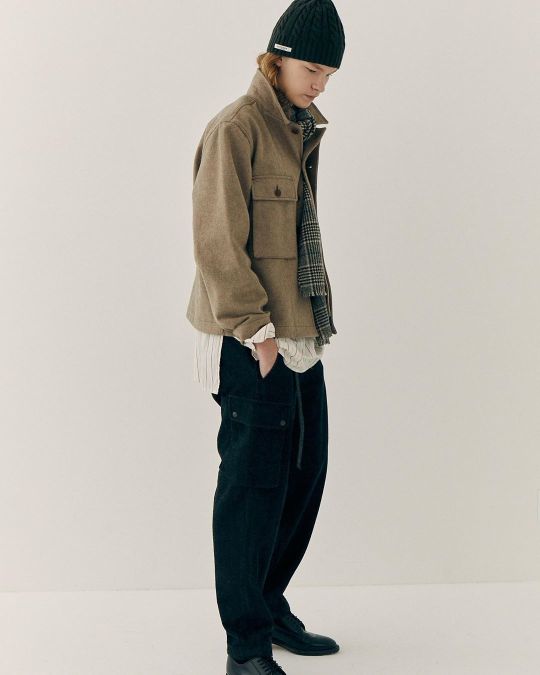

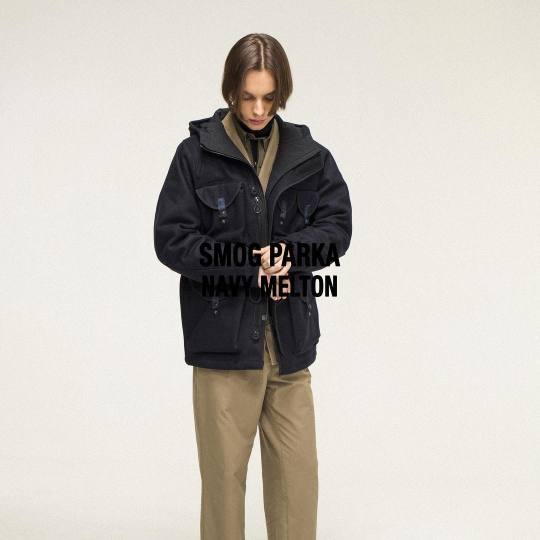

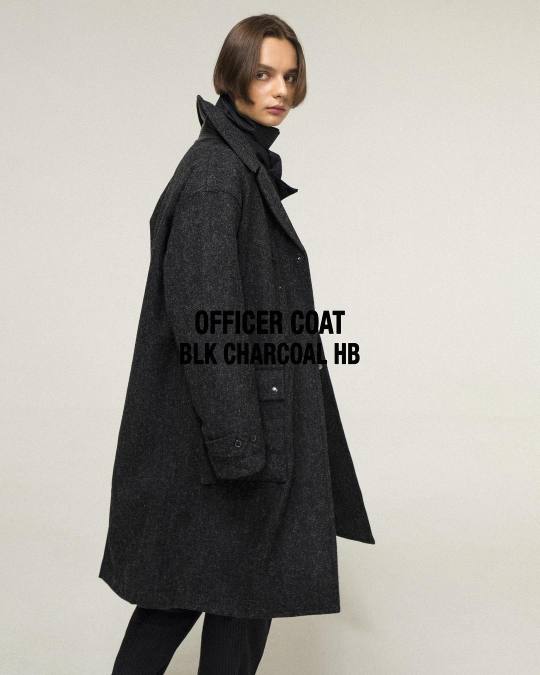

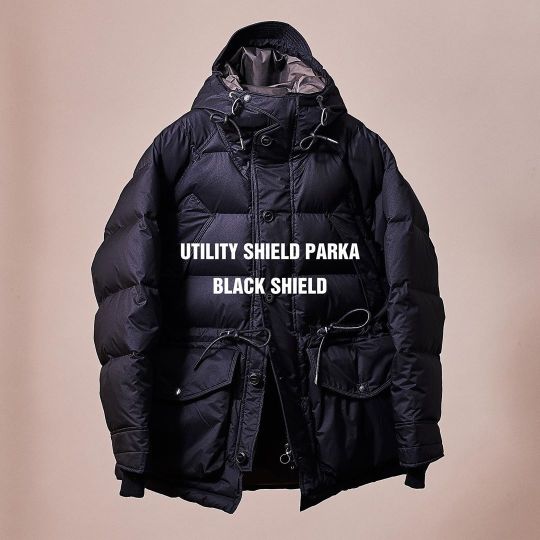

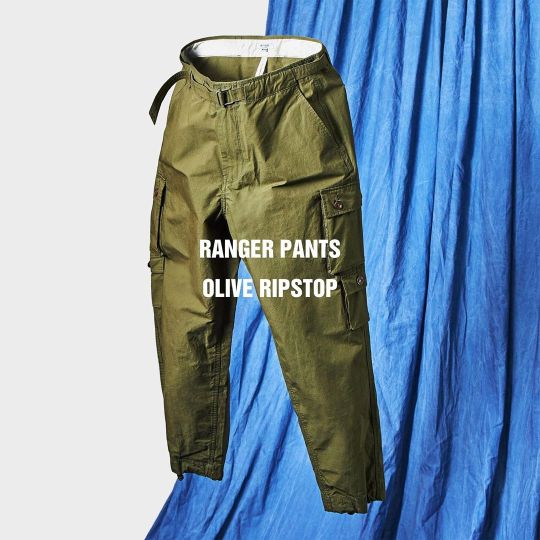

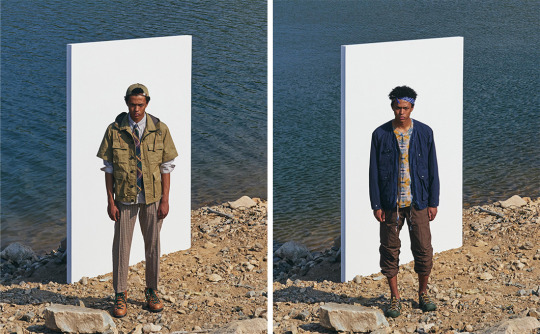

There are a few things you can almost always find from Eastlogue, although the designs are often tweaked from season-to-season. Their M70 parka takes inspiration from a Swiss Army jacket by the same name. It features spacious bellow pockets, a wind-blocking placket, and a snap-in mesh veil (for when you literally want to throw shade). When you fasten the jacket, there’s a zipper hidden behind the placket so you can quickly reach into the interior. I also love their take on the iconic dispatch rider coat, which British officers wore during the Second World War, and the cheeky fleece jacket they call their Traveler. The fleece jacket is inspired by fishtail liners, which the company has transformed into a utility jacket. The front pockets are a design quirk borrowed from traditional hunting wear, while the detachable hood and adjustable cuffs make the coat practical and stylish. “Our strong point is in goose down jackets,” Dong Ki tells me. “I consider our Utility Shield parka to be our signature model.” The company also has one of the coolest collections of technical pants, as well as collaborations with everyone from New Balance to the Korean bag company Blankof.

The clothes are inspired by historical pieces, but they’re never literal reproductions. There’s always something different about the fit, fabrication, or detailing. “I think our work is closer to a reinterpretation of the past, rather than creating something from nothing,” Dong Ki says. “When we start a new collection, we begin with a concept. There are a few designers on the team and we discuss the concept for the season, the lookbook, the color combinations, and the designs. Once we have our designs, we try to find the right fabrics. If we can’t, we make them. Since Eastlogue is a Korean brand, I trust Korean manufacturing skills, so we make our clothes here. I think this is an attractive selling point for our overseas customers. Plus, since South Korea has free trade agreements with many countries, our Korean-made goods are easier to export.”

When browsing around online, you may find that Eastlogue is associated with a family of companies, much like how Engineered Garments orbits within a family of brands around Nepenthes. The relationships here, however, are a bit easier to parse out. Eastlogue is the company’s workwear label, while Unaffected is the slightly smaller brother brand. As both companies were growing, Dong Ki sold them under his Seoul-based flagship store FR8IGHT (formerly known as Sortie). Riot is also the parent company for all these names. “The name FR8IGHT means ‘to put our taste in this place,’” Dong Ki explains. If you’ve ever wondered what you can wear with Eastlogue, you can just browse their online shop to see what they like in terms of New Balance sneakers, country Paraboot shoes, Harley of Scotland Shetlands, and 1960s-styled Tart Optical eyewear.

I asked Dong Ki if he has any suggestions for must-visits when people go to Seoul. “Seoul is changing rapidly every day,” he tells me. “There’s no guarantee that a good place to spend on this trip will be a good place on the next trip. But I think that’s the charm of this city; its flow is so rapid. I think you can find the charm in Seoul if you just enjoy the city on its own.”

Readers interested in Eastlogue can find the label in the US through Namu Shop and Division Road, both sponsors on this site. Namu’s spring collection mostly consists of warm-weather field shirts and lightweight outerwear, while Division Road has standard-issue jackets and pants designed to be worn from spring through fall. You can also follow Eastlogue on Instagram and YouTube (there are video lookbooks!). Special thanks to Dong Ki Lee for taking the time to answer my questions, as well as Kwang Su Ko for translating.