About a month ago, as I was walking home from work, I made a mental note to call my barber and make an appointment sometime that weekend. A friend of mine’s wedding was approaching, and I was two weeks overdue for a cut. But on March 16th, when seven Bay Area counties issued a sweeping stay-at-home mandate, all non-essential services in my neighborhood were shut down overnight. Truthfully, even if the quarantine order was lifted tomorrow, I’m not sure I’d feel comfortable going to the barbershop anytime before June. So I’ve resigned myself to looking like Shaggy Rogers, the lanky slacker in the Scooby-Doo franchise. By June, I suspect I’ll look like an ugly version of Fabio.

I’m still unsure how I should dress when living under quarantine. Online, I’ve seen some people go as far as wearing a coat-and-tie, but I mostly wear the same uniform Bruce Boyer describes for himself in this Drake’s article: “either khakis or jeans (the older, the better), a casual button-front shirt (chambray, flannel, drill, or whatever suits the season), and camp mocs (again, the older, the better).” The only difference is that I also wear a baseball cap (like the rest of the uniform, the older, the better). These days, when I start feeling cabin fever — which is often — I find it helps to out for a brisk walk around the neighborhood (safely, of course, and away from other people). Going out for a walk keeps my blood moving, clears my mind, and keeps me feeling connected to the outside world. Since these outings are brief, however, I don’t want to style my hair. So I’ve been throwing on a baseball cap, which is currently my only wardrobe essential.

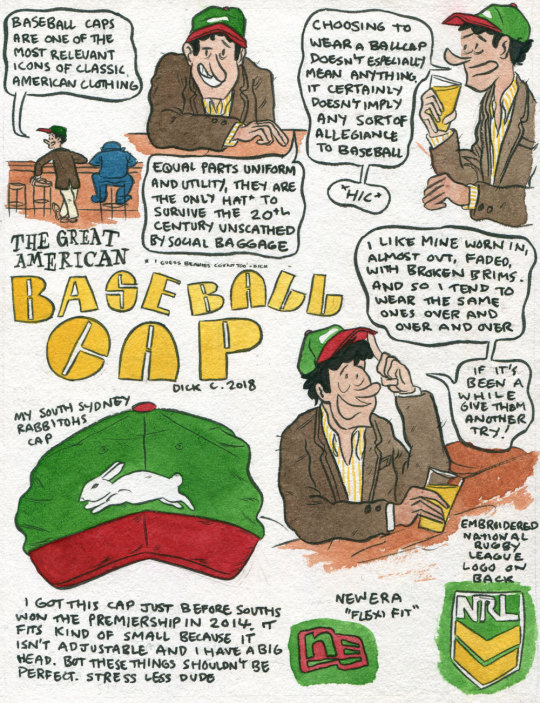

The baseball cap is the only headwear style to have made it out of the 20th century unscathed. Its popularity can be explained using the same themes that have driven the history of men’s dress: democratization, the confluence of commerce and art, and how something can be used to express tribal identity. Most of all, the style has become so ubiquitous in American culture, you could call it America’s national hat. In an ode to the style published in The New York Times, Troy Patterson called this sporty headpiece “the common man’s crown.”

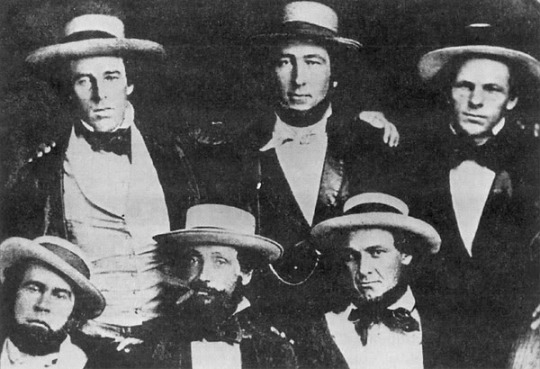

The first caps appeared on the baseball field in 1849 as part of the New York Knickerbocker Baseball Club’s team uniform. Back then, the baseball cap was made from woven straw, much like a boater, and it was worn with white flannel shirts and blue woolen pantaloons. Contrary to popular belief, baseball players didn’t wear them to keep the sun out of their eyes, but simply because respectable men covered their heads when they were in public. These were, after all, men who were just as prosperous as they were convivial. The Knickerbockers team was made up of insurance salesmen, Wall Street stockbrokers, a United States marshal, a portrait photographer, a physician, and a cigar dealer. “We were all men who were at liberty after 3 o’clock in the afternoon,” one of them remembered, “and we played only for health and recreation.”

About ten years later, members of the Brooklyn Excelsiors introduced the progenitor of the modern baseball cap. This one had a rounded crown, an extended bill that took inspiration from the jockey’s cap, and a fabric covered button known as a squatchee. When straw proved to be a poor material for a baseball cap — as it didn’t absorb sweat and it blew off too easily in the wind — club members replaced it with wool. Later, the front of the cap was reinforced with a stiff cotton material known as buckram, which served to raise the front of the cap’s silhouette, much like how a tailor might use haircloth and canvas to add shape to the front of a suit jacket. In this way, the front of the cap’s crown could more proudly display a team’s emblem.

To get a sense of how the baseball cap has come to dominate our culture, you only need to look at photos of the first-ever World Series baseball game, which took place between the Boston Americans and Pittsburgh Pirates in 1903. Spectators that day arrived at the stands wearing all styles of headwear: derbies, bowlers, checkered caps, teardrop fedoras, and boaters. Only the players on the field wore baseball caps. In his book Ball Cap Nation, which traces the history of America’s love for this crown, journalist James Lilliefors writes:

Until the late 1970s, wearing a ball cap anywhere but on the baseball field carried with it a cultural stigma – a stigma reinforced by decades of American films and television shows, which often depicted cap-wearers as comic or marginal characters. In the mid-1930s, Scotty Beckett pioneered the sideways/backwards ball cap look in Our Gang comedies (a look likely inspired by Jackie Coogan’s oversized wool cap in Charlie Chaplin’s 1921 film The Kid). Huntz Hall portrayed the buffoonish Horace Debussy “Sach” Jones in the Bowery Boys movies from 1946 to 1958, with his trademark flipped-brim ball cap.

The style was adapted in the 1960s by backwoods mechanic/gas station attendant Gomer Pyle on The Andy Griffith Show and was parodied in the 1970s by Rick Nielsen of the rock band Cheap Trick. Then there was the Beav – Theodore “Beaver” Cleaver – who frequently wore an unlettered ball cap on the 1957-1963 sitcom Leave It to Beaver. And Oscar Madison, the slovenly half of The Odd Couple, who donned a Mets cap in the 1968 movie (when the Mets were still lovable losers) and on the 1970s television show. Not to mention Klinger on M*A*S*H in the 1970s, with his Toledo Mud Hens cap. […] There are other examples – but few, if any, before 1980 portrayed cap-wearers as heroes or sex symbols. For the longest time, baseball caps simply got no respect.

You can still see that stigma today in shows such as The Sopranos, where Tony Soprano – an actual mob boss and murderer – gets worked up about seeing a young man break social customs by wearing a baseball cap inside an upscale restaurant. “That’s one of the things I hated most when I had my restaurant,” Artie Bucco says in the scene, while shaking his head at the mundane degeneracy. “It’s values today; standards are crumbling.” The scene currently has more than 6.5 million views on YouTube – and it’s just about Tony Soprano telling a guy to take his hat off.

So how did the baseball cap replace all the other headwear styles seen at that 1903 World Series game? And why is it so popular despite also being so reviled? Lilliefors gives a few hypotheses. First, he suggests that the rise of the baseball cap is directly tied to the sport itself. As television broadcasting made the game more popular, fans started to want to show support for their team even outside of stadiums. In the 1960s, agricultural companies picked up on the idea that you could use the baseball cap for advertising other things, hence the birth of the trucker cap. After that, other companies followed. Men such as Tom Selleck in Magnum PI and Tom Cruise in Top Gun also gave the baseball cap a necessary rebranding – first making it acceptable, then fashionable, and finally even heroic.

It was at this point when the baseball cap got swept up by a confluence of art and commerce. Culturally, it was everything: a useful garment you can wear, an inexpensive thing to produce, a cheap item to purchase, a marketing tool, a souvenir, and a symbol of identity. The story of how the baseball cap became popular is similar to the rise of graphic t-shirts and tote bags. In the last few decades, these items have been an easy way for businesses to advertise themselves, as well as for people to signal their tribal affiliations. In Marshall McLuhan’s words, the medium is the message.

The baseball cap also intersected with some powerful narratives that have driven post-war fashion: the cult of youth, our inclination for sportiness, and the populist preference for informality. “As the cap became mainstream, men and women began to play with the style, turning it backwards or sideways as a symbol of personal expression,” writes fashion historian Maude Bass-Krueger in Vogue. “The headgear was adopted by musicians, from rappers to punk rockers and grunge singers in the 1990s to pop stars and the MTV generation in the 2000s. Celebrities began to use the hat as a way to shield their faces from the paparazzi. As it gained popularity, the style also crossed borders. Young British middle-class urbanites adopted the baseball hat as part of their standard uniform in the early 2000s. Today, the baseball cap or trucker hat is sometimes worn ironically or as a way to demonstrate affiliation with the working class.”

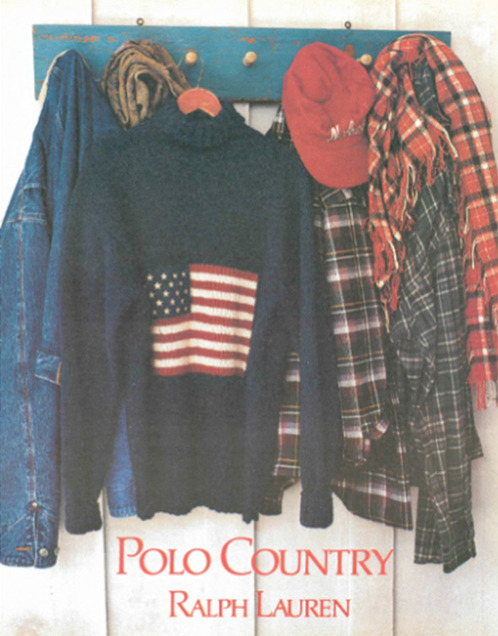

For years, the baseball cap has been mostly shunned or ignored in the more tailored corners of men’s style, but it feels like it’s coming back around again. When I was growing up, the coolest looking guys I knew wore Polo Ralph Lauren head-toe-toe. Many of them topped off their outfit with a Polo Sport or Sportsman cap, much like how Jonathan Edwards of Milan Style is dressed above (the photo is from Jamie Ferguson’s beautiful book of menswear portraits, This Guy). I was also surprised to see Simon Crompton sport a baseball cap on his blog, Permanent Style, a few weeks ago. “I like [the cap] with pieces that sit someway between casual and formal: a raglan coat rather than a tailored overcoat (smart) or a blouson (casual); and suede boots or loafers, rather than oxfords or trainers,” Simon wrote. The more skeptical readers in his comment section said this outfit would have looked better with a beanie, but I remember when beanies carried even more social baggage. The fact that beanies have now been reframed makes me think that the acceptance of ball caps isn’t far behind.

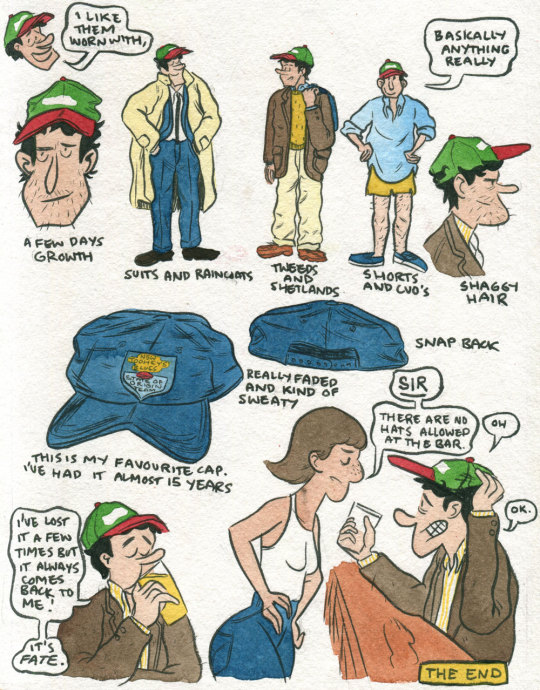

Tony Sylvester says he understands the skepticism. “Ball caps come with a heap of connotations, many of them negative,” he says. “They’re so ubiquitous; it can be difficult for someone who’s trying to make their sartorial mark to see their charms. But I also think the baseball cap is a common signifier of a kind of youth culture that many people in my generation grew up with: hardcore, hip hop, skating, etc. So for me, it’s an early ‘real-time’ piece of attire, rather than some of my more affected or ‘learned’ inspirations. I don’t know if I would wear one with a suit, but maybe a sport coat. A Teba jacket, for sure. And definitely casualwear. I think a baseball cap can be infantilizing if not handled correctly. As you get older, you have to proceed with more caution.”

Tony tells me that some of his favorite caps include Papa Nui, Rowing Blazers, and a “killer long-bill from Quaker Marine.” He also collects various commercial hats, such as the ones above advertising obscure champagne brands and The Royal Scotsman train. I was both surprised and pleased to hear it, as such hats are among my favorites as well. A couple of months ago, I bought a wool-and-suede Quaker Marine Swordfish, which is a fishing cap, a cousin of the ball cap. The seafaring bill is a bit longer, which allows it to do the important job of blocking glare out of your face. But there’s also something about the tweaked design that allows it to pair well with Americana and workwear. Brian Davis, who sells the line at his shop Wooden Sleepers, counts the Swordfish as one of his all-time favorite hat styles.

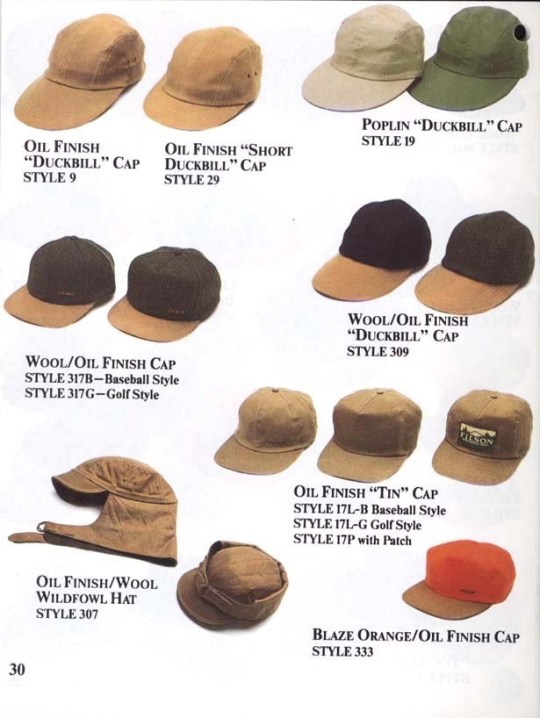

“I think ball caps suit my style better than more ‘classic’ styles of headwear,” Brian tells me. “I dress pretty casually, and I don’t wear a hat just to wear one. I don’t even consider myself to be a ‘hat guy.’ I just wear them to keep the sun out of my face, which is why I like the long-bill Swordfish and Oysterman from Quaker Marine so much. Polo and Filson made some great long-bill hats in the 1990s. I try to snag those when I can. I’m always trying to find vintage military caps, especially in HBT or OG-107 fabric, as well as vintage hunting, fishing, and trapping-style hats.”

When shopping for a cap, think through the design’s details. It’s often easiest to just buy from a shop or brand that closely aligns with the rest of your wardrobe. Self Edge, for example, sells military-inspired Papa Nui caps, which pair well with denim and workwear. Similarly, Outlier’s Supermarine cap may look simple enough, but it’s made from a slightly techy fabric that would make it look more at home with techwear. Rowing Blazers is probably best kept to modern prep and Americana; Paa with minimalism; Patagonia, Gramicci, and Nike ACG with gorpcore.

Silhouette also matters greatly. Baseball caps are usually made with a raised crown, whereas dad caps sit lower on the head. Quaker Marine’s seafaring caps are defined by their elongated bills. Sometimes a design looks better in some outfits than others, but it’s hard to know what you prefer without trying things on. I like Ebbets Field Flannels and Ideal Cap Company’s vintage-styled caps with the sort of classic Americana and workwear seen on The ResQ’s Instagram account. I wear my Quaker Marine with slightly more offbeat versions of workwear (I think the tweaked silhouette lends something). I don’t wear caps with tailored clothing, but if I did, it would be something like this Norse Projects x Loro Piana dad cap. Jeremy Kirkland of the excellent menswear podcast Blamo! wears this sort of look well.

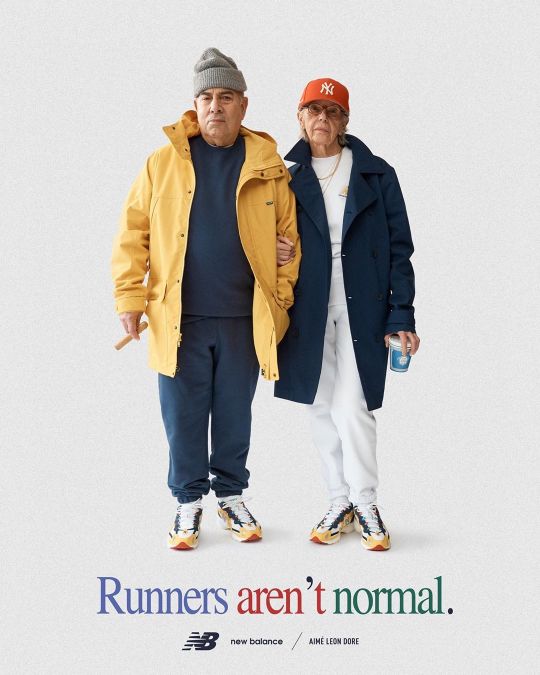

If you’re looking for a simple and logo-free cap, start with Stephan Schneider, Kuon, Paa, Mollusk, Viberg, Norse Projects, American Trench, 3sixteen, and most affordable of them all, J. Crew. Caps without logos or emblems will always be the most visually neutral, but I also think that something with a bit more design can add something to an outfit. As I mentioned, Ebbets Field Flannels and Ideal Cap Company make some excellent vintage-style baseball caps. Division Road, a sponsor on this site, has some in a tasteful script. I also like Battenwear, Corridor, Filson, Free & Easy, Polo Ralph Lauren, Aime Leon Dore, 18 East, and Argot, as well as the preppier designs from Rowing Blazers, Mister Mort, and O’Connell’s (a needlepoint buffalo!).

You can also choose a cap in the same way people have always adopted a cap: get one that shows your support for something. “I think a hat can be lighthearted,” says Brian. “You can grab something from one of your favorite spots, such as an ice cream parlor or a pizzeria. I’m from Long Island, so I have a dad hat from the Long Island Farm Bureau.” If you don’t have a favorite team, get something that means something to you. PBS and The New York Times, for example, both sell well-designed caps. Graeme in Australia, who always looks exceptional, has been wearing a ball cap supporting his favorite tailoring shop, P. Johnson.

Lastly, there’s the issue of customization. In high school, I remember bending and breaking-in caps to get them to look like how I wanted — rolling the brim, soaking them in water, and even cutting out the buckram. Some guys like their brims razor straight, others curved, and others still bend them into a V. “This is the simple start of asserting a further level of ownership,” Troy Patterson writes at The New York Times. “The particular charm of the pluralistic character of the ball cap has to do with its ability to communicate expansively within strict formal limits. […] A ball-cap designer who deviated from the mean — by perceptibly abridging the bill, say, or by altering the ideal simplicity of the crown — would be making a fashion statement that fundamentally rearranged its meanings beyond recognition. The cap is not a fashion item, but something larger and more primal: the headpiece of the American folk costume.”

For those who still protest, let me say this: a baseball cap is more appropriate for summer than a beanie, and it looks better than me with long hair.