Earlier this month, Dartmouth professor and labor economist David Blanchflower published a study on the statistical relationship between well-being and age. Using data from 132 countries, Blanchflower found that people often become increasingly miserable as they head into their 40s. Colloquially known as the mid-life crisis, economists represent this trajectory with an inverted U-curve (for those who aren’t mathematically inclined, such as me, this is shaped like a “frowny face”). This pattern has been long known to psychologists, philosophers, and mystics, but Blanchflower found the exact age when the average midlife crisis peaks: 48, give or take a year depending on some conditions. “The curve’s trajectory holds true in countries where the median wage is high and where it is not, and where people tend to live longer and where they don’t,” he writes. The good news is that, according to science, things indeed get better. After age 48, people slowly start to find contentment.

Why is this? Some suggest this statistical pattern is hardwired into our biology. A 2012 study of chimpanzees and orangutans found that our closest evolutionary ancestors also fall into middle-aged ruts. Theirs tends to peak at the age of 30, which closely traces along the human timeline (a little past the midway point for life expectancy). The study’s methodology, however, is questionable at best. Accurately measuring happiness in humans is notoriously tricky, so you can only imagine what it’s like for great apes. “Each ape has several keepers, and every keeper was asked to assess the psychological well-being of their particular animal using a short questionnaire,” explains co-author Andrew Oswald. Among the questions, keepers had to answer: “If you were that animal, how happy do you think you would be on a scale of 1-7?” (I found this question to be so hilarious, it briefly relieved me from my miserable existence).

Economists don’t yet know why life gets better after age 48, but they have a few ideas. It could be that people learn to quell their unreasonable aspirations after mid-life, as well as adapt to their strengths and weaknesses. They may learn to compare themselves less to others or appreciate their remaining years as similar-aged peers pass on. A more straightforward explanation could be that the population sample at the end of the age spectrum is biased. Happier people tend to live longer, so the inverted U-curve simply reflects who has managed to stick around.

Another theory is that we learn how to live with our mistakes. When we’re young, many of us expect to eventually achieve perfection in various areas of adulthood. We imagine ourselves one day being in a happy and harmonious marriage, owning a home, earning the respect of our peers, and being engaged in deeply fulfilling work. But the best-laid plans of mice and men often go awry. Somewhere along the way, cracks and fissures start to appear in our plans, and small decisions compounded over time have a way of taking us to unexpected places. It’s then that we begin to ruminate over the “what ifs.” What if I had done this and not done that? Most of all, what if my life turned out differently?

As I’ve gotten older, I’ve found that it’s easy to spiral into regret. You start to ruminate over what you did or did not do, and suddenly all your failures come into full relief. A psychology study at UC Berkeley found that, when those moments happen, you can learn and grow from mistakes by facing them directly with some self-compassion. “Regrets are common,” writes psychology professors Jia Wei Zhang and Serena Chen. “Instead of wishing to go back to un-do or do, what people can do right now is confront these regretted life experiences with self-compassion, paving the way for personal improvement.” It helps to situate one’s shortcomings as part of the common human experience. To fail is to live a fuller life.

This is easier said than done, of course, but perhaps that’s why older people are more content. The movie cliche, “I wish things could just go back to the way they were,” suggests that we should be able to move onto good times, but as though the bad times never happened. Maybe as you get older, you learn how to embrace, rather than trying to erase, those memories.

Kei Shigenaga, a relatively new jewelry label based in Japan, represents some of these ideas through finely crafted accessories. The label was started a few years ago by two friends who met in New York City. Wataru Shimosato, a thin, long-haired Japanese model with a talent for photography, serves as the company’s creative director. Then there’s Kei Shigenaga, the company’s namesake and silversmith, who makes all of the jewelry by hand in his Tokyo-based studio.

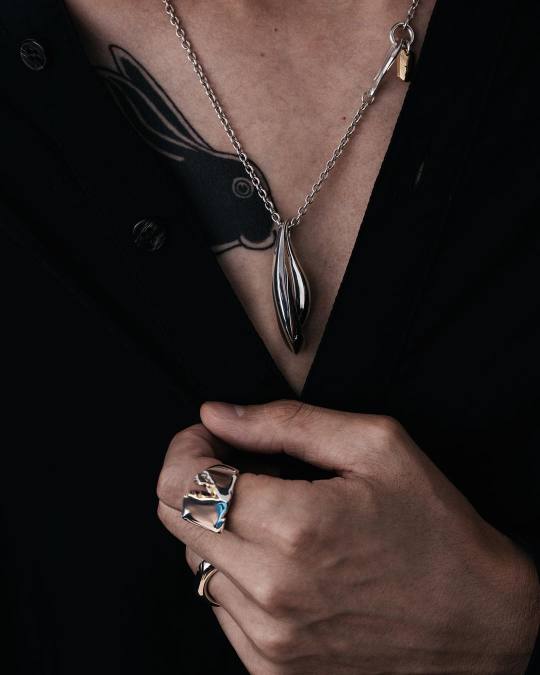

Even though these are glimmering, shiny pieces rendered in sterling silver or gold, Kei Shigenaga’s jewelry pieces feel dark and brooding. There’s a running tension between the image of fine jewelry as being something delicate here, but also tough. “Jewelry isn’t just about fashion, it can also be an art object that you can have with you every day,” the Japanese silversmith once told Eugene Rabkin at StyleZeitgeist. “In my work, I try to concentrate on the roughness of precious metals.”

For his designs, Shigenaga takes inspiration from traditional Japanese culture. The twin, sterling silver pendants on his Ryu necklace, which almost look like liquid silver droplets, represent the two carps in Japanese lore. According to legend, a school of fish was swimming up the Yellow River one day when they approached a waterfall. When the current started to get too rough, most of them turned back. But two koi fish remained and spent the next hundred years trying to swim up the cliff. At last, when they reached the top, the Gods turned these two spiraling carps into a beautiful golden dragon. That’s why koi fish are used in Japanese tattooing to represent strength, independence, and perseverance. It’s said that their nature is to swim upstream.

In the last year or so, Shigenaga has been inspired by kintsugi, the Japanese art of repairing broken ceramics with a gold-peppered lacquer. The method supposedly dates back to the Muromachi period when 15th-century Japanese shōgun Ashikaga Yoshimasa accidentally broke his favorite tea bowl. He sent the broken ceramic pieces back to China for repair, but upon the bowl’s return, Yoshimasa was horrified with how the shards had been affixed together using ugly metal staples. So he tasked his local craftsmen with finding a more aesthetically pleasing solution. The method they came up with was later known as kintsugi – kin meaning golden, tsugi for joinery. Instead of trying to disguise the fault lines and render them invisible, these craftspeople made something artful out of the broken pieces by gluing them together using a golden lacquer.

As a philosophy, kintsugi can be seen as part of the broader Japanese tradition of wabi-sabi, which cherishes that which is simple, unpretentious, and old. This idea, which underscores some themes in Zen Buddhism, says that old, weathered items shouldn’t be neglected or discarded, but valued and repaired with enormous care. Kintsugi is also similar to the Japanese idea of mushin, or “no mind,” which carries connotations of “fully existing within the moment, of non-attachment, of equanimity amid changing conditions, of removal from the desire to impose one’s will upon the world.” In her essay “A Tearoom View of Mended Ceramics,” published in the anthology Flickwerk, Christy Bartlett writes about the philosophy behind Japanese ceramics:

Mended ceramics foremost convey a sense of the passage of time. The vicissitudes of existence over time, to which all humans are susceptible, could not be clearer than in the breaks, the knocks, and the shattering to which ceramic ware too is subject. […] Mended ceramics convey simultaneously a sense of rupture and of continuity. That one moment in which the incident occurred is forever captured in the lines and fields of lacquer mending. It becomes an eternally present moment yet a moment that oddly enough segues into another where perishability is circumvented by repair. Simultaneously we have the expression of frailty and of resilience, life before the incident and life after. Yet the object is not the same. In its rebirth, it assumes a new identity that incorporates yet transcends the previous identity. Like the cycle of reincarnation, one life draws to a close and another begins.

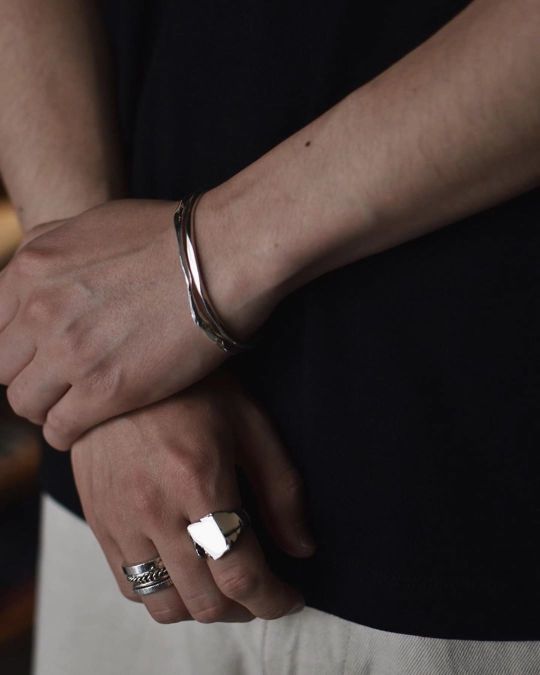

Shigenaga’s jewelry isn’t literally broken and then repaired with kintsugi, but the company makes their rings, bangles, and even hair ties to mimic the aesthetic. Fault lines are built into the sterling silver pieces, and then molten 18k gold is poured into the cracks. If I had one criticism, it would be that it can be hard to spot the contrasting gold lines at first. The detailing is faint and subtle, but on the upside, this also makes it easier to match metals in an outfit. And, perhaps, it would be missing the point if you were to insist on perfection from a kintsugi-inspired object.

There is, of course, the argument that, like pre-distressed clothing, kintsugi jewelry mistakes the aesthetic for substance. Since kintsugi’s introduction 600 years ago, Japanese craftsmen have been accused of purposely breaking ceramics, repairing them with gold, and selling the objects to elites who are hungry for commitment-free spirituality. Admittedly, there’s also something mawkishly sentimental about the symbolism. But in an age that values youth and perfection, the art of kintsugi says we should value that which is scarred, broken, or imperfect, starting with ourselves and those around us. I like Kei Shigenaga’s jewelry as a reminder of that wisdom.

Last year, I bought one of their chunky Koryu rings on a whim and I’ve been surprised by how often I reach for it. The style naturally goes with brooding contemporary lines such as Lemaire, Robert Geller, and Stephen Schneider. I also find that it fits right in with Western-styled workwear, such as a suede trucker jacket worn with a corded Western shirt and some slim jeans. So long as the outfit has a bit of an edge – more Nine Lives or Margiela’s five zip, rather than a navy sport coat worn with grey flannel trousers – I think these rings make for a nice finishing touch.

Kei Shigenaga’s jewelry used to only be available through made-to-order, which meant that all sales were final. In the last few months, a couple of stores have picked them up as part of their stocked inventory. This makes it infinitely easier to figure out your size, as well as return things if you decide you don’t like how the pieces look on you. You can find a selection of their jewelry at SSENSE and Self Edge. At the moment, Self Edge only carries two of the models in-store, the Kyo and Shisui. However, Kiya tells me they’re getting more shipments later this season and they’ll be online soon. I’ve been thinking about buying the battered, blank signet ring that Kei Shigenaga calls their Kyoka. It can be dicey to wear multiple rings on one hand, but Kei Shigenaga’s designs, as evidenced by the photos below, are perfect for this kind of thing.

For more of Kei Shigenaga, you can find them on Instagram and YouTube. Shimosato also has a great street style blog called An Unknown Quantity, where you can find familiar faces such as Visvim’s Hiroki Nakamura, Rare Weave’s Hartley Goldstein, and Stoffa’s Agyesh Madan. For actual kintsugi objects, check Etsy. Various sellers there have repaired teacups, bowls, and other ceramics.