Every two months at The Economist, you can find Adrian Wooldridge opining about the modern world through his column, The Bagehot. Nearly all of his articles follow the same formula. He bemoans the lack of etiquette and grace in today’s society, and then ends with a heavy-hearted sigh. He hates how the young, who are the most educated generation in history, are more likely to model their style after the urban underclass, rather than yesterday’s educated elite. As a committed pogonophobe, he thinks beards represents the mainstreaming of male vanity. He snarks on athleisure. Predictably, he also hates seeing tattoos, piercings, and, most of all, bare male ankles. He wishes we still had the respectability of the fedora. You can almost hear the smugness in his voice when he writes: “These days, hat-wearing is a snub to authority rather than a sign of respect. The most popular hats are the ugliest: baseball hats that look like giant duck-bills, plastered with an inane slogan, and beanies that could double as tea cozies.”

In an October/ November 2018 column, Wooldridge laments the collapse of manners. According to him, 16th century Europeans behaved like barbarians. They reveled in torture and public hangings; they stank to high heaven. “It took centuries of painstaking effort –- sermons, etiquette manuals, and stern lectures –- to convert them into civilized human beings,” he says. Now, however, after nearly 500 years of the civilizing process, all has been undone in just a few decades. People eat food on trains, and public bathrooms are a mess. San Francisco, a boomtown for tech-driven growth, is littered with feces, syringes, and garbage. The people who were supposed to guard high culture, such as academics, have collectively turned against it. At the end of his essay, he admits to almost serial-killer-level behavior, which he excuses as his way of just trying to keep up with a de-civilized world.

I don’t think I’ll ever give in to the fashion for beards and tattoos, let alone turning up to meetings naked. But I’ve noticed that I increasingly circumvent the normal rules of politeness in a desperate attempt to keep going. I carry a pair of headphones with me at all times to insulate myself from the noise of my neighbors. I sprint ahead if I see any possible competitors approaching the queue for coffee. And I’ve graduated from putting my bag on the seat next to me on a train to a more cunning technique: I leave a copy of Jack Rosewood’s “The Big Book of Serial Killers” on the chair and smile maniacally at anyone who comes anywhere near. So far, the serial-killer strategy has worked remarkably well.

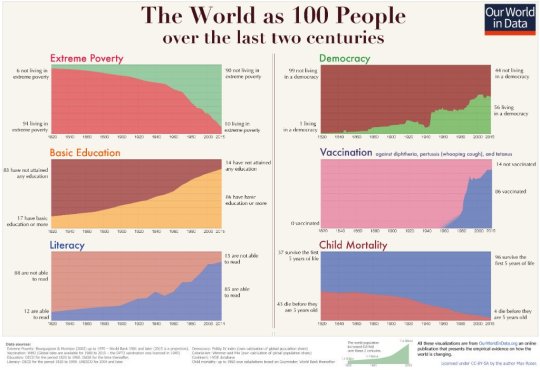

By any serious measure, the world has gotten better. Just check out Our World in Data, an online statistical publication managed by developmental economist Max Roser. One of the reasons why people don’t see progress in the world is because they’re unaware of how truly terrible the past was. In the early 1800s, 90% of all people lived in extreme poverty, and about 45% of all children died before their fifth birthday. Today, thanks to improved health, wealth, and access to education, those numbers are down to 10% and 4%, respectively. Since 1950, global life expectancy has grown from 45 to 71 years. In Western Europe alone, homicide rates have fallen from as high as 20% in 1800 to less than 1% today. (Although, notably, these statistics are not without controversy).

Yet, the idea that the world has gotten worse persists, and it’s easier than ever to find this sentiment in menswear culture. Among men who love suits and sport coats, the demise of traditional tailored clothing represents a kind of fall from grace. A three-piece, dark worsted suit, in either navy or charcoal, is the symbol of Renaissance splendor. Wearing something casual, on the other hand, demonstrates laziness, lack of pride, and untutored behavior. It can be difficult to escape the vexations of petty tyrants — everyone is judgmental about fashion. Still, few are so judgmental as the person who thinks suits are the only legitimate aesthetic, as their judgments often preloaded with ideas about the past and morality. For them, respectability is connected to what’s on your head, not what’s inside of it.

Sometimes I wonder if these people really believe the things they say, or if they’re just trying to signal some kind of Victorian virtue, the epitome of bourgeois sensibility. In the early 19th century, Western Europeans and Americans talked about respectability in ways that are strikingly similar to how we talk about it now. And there was a subtext to these conversations that made them about much more than clothes.

During the late 1800s, when the suit was still considered workwear garb, polemical writers drew a straight line from the condition of a person’s moleskins to their morality. As Christopher Breward points in his book The Suit, “the neglect of sartorial appearance was for many but a symptom of moral laziness and even criminality, and poverty was seen as no excuse for untidiness.” In a prescriptive, pocketbook guide to manners published in 1882, Samuel Pearson presented the dirty rags of the “unwashed masses” as evidence of their fecklessness. An excerpt:

The working classes of England are far behind those of France in the matter of dress. In Normandy, you are met with the neat, white, well-starched cap; in Lancashire, with a tawdry shawl […] The men are worse. They never seem to change their working clothes when the day’s work is over. Those who go to chapel and church have a black or dark suit for Sunday wear, generally creased and often ill-fitting, but on other days, it is seldom that you meet with a nicely dressed working man or working woman. I have seen political meetings attended by men who had taken no trouble to wash off the dirt of the day either from their faces or their clothes.

Edward Carpenter, the progressive writer in late 19th-century England who wrote on socialism and sexual freedom, knew these judgments all too well. Born to a privileged family in 1844, Carpenter did exceptionally well in school while growing up in Sussex. Upon graduation, he was invited to tutor the princes George Frederick (later King George V) and his elder brother, Prince Albert Victor, but he declined. Instead, he moved to Leeds, where he joined a group of academics hoping to bring higher education to deprived areas of England. Carpenter wanted to teach astronomy to working-class people, but when he found that his classes were mostly attended by middle-class students with little interest in his subject, he felt disillusioned and dispirited.

Carpenter eventually moved to Sheffield, where came into contact with manual workers and began writing poetry. Influenced by the works of William Morris, John Ruskin, and Henry Thoreau, Carpenter developed ideas about a utopian society that can be roughly described as primitive communism. He was an anti-modernist, anti-industrialist, and, most of all, an anti-capitalist. Rattle off any progressive cause today, and Carpenter championed it nearly 120 years ago. He campaigned for women’s rights, clean air, and a living wage, rallied against corporal and capital punishment, and was a prominent advocate of vegetarianism. His most radical act, however, was living openly as a gay man with his partner George Merrill during the Oscar Wilde trial. Remember, homosexuality was considered a crime at this time. Wilde’s trial not only generated hysteria about homosexuality in high society, the Irish playwright was also sentenced to two years of hard labor for “gross indecency.” “Eros is a great leveler,“ Carpenter remarked in The Intermediate Sex. “Perhaps the true Democracy rests, more firmly than anywhere else, on a sentiment which easily passes the bounds of class and caste, and unites in the closest affection the most estranged ranks of society.”

As a member of the Fabian Society and other British socialist organizations, Carpenter often criticized the hypocrisy of polite Victorian elites. He hated the notions of respectability in dress and called for not only the abolition of restrictive clothing styles but even the concept of Western fashion. For Carpenter, the heavy seams and drapes of a well-tailored suit weren’t so much a democratic uniform, but a prison. In an essay about the virtues of a simple life, Carpenter declared:

The truth is that one might almost as well be in one’s coffin as in the stiff layers upon layers of buckram-like clothing commonly worn nowadays. No genial influence from air or sky can pierce this dead hide […] Eleven layers between him and God! No wonder the Arabian has the advantage over us. Who could be inspired under all this weight of tailordom? And certainly, nowadays, many folks visibly are in their coffins. Only the head and hands out, all the rest of the body clearly sickly with want of light and air, atrophied, stiff in the joints, strait-waist-coated, and partially mummied.

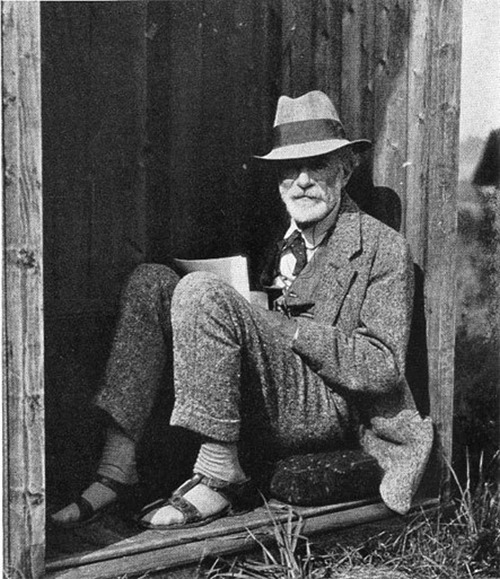

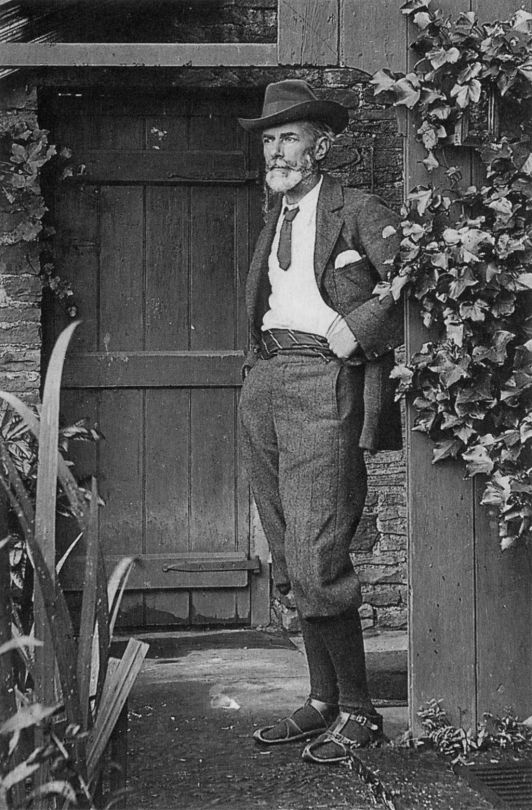

In the photo above, you can see him in a working man’s suit with a pair of leather sandals that he fashioned for himself (they were modeled after a pair he received from India as a gift). At a time when proper gentlemen wore laced-up balmoral and button boots, Carpenter defiantly went open-toed. Continuing in his essay:

As to the feet, which have been condemned to their leathern coffins so long that we are almost ashamed to look at them, there is still surely a resurrection possible for them. There seems to be no reason except mere habit why, for a large part of the year, at least, we should not go barefoot, as the Irish do, or at least with sandals. [Democracy, which redeems the lowest and most despised of the people, must redeem also the most menial and despised members and organs of the body.]

For Carpenter, Victorian dress codes and conventions weren’t really about civility at all, but rather class signaling and social hierarchy. While Victorians preached the importance of being kind and polite, they were polluting England and living off the work of the laboring classes. In May 1889, Carpenter wrote a letter to The Sheffield Independent about how 100,000 of the city’s residents were struggling to find sunlight and air, enduring miserable lives, and dying of illnesses because of the thick, black cloud of smog arising out of factories like smoke from Judgement Day. Meanwhile, as these Melton-clad plutocrats wagged their fingers and nattered on about proper dress codes, they concealed their cruelty and vulgarity under refined manners. They weren’t concerned with virtue, but rather showing their supposed higher moral status. Those socially under them then aped those manners to seem higher class.

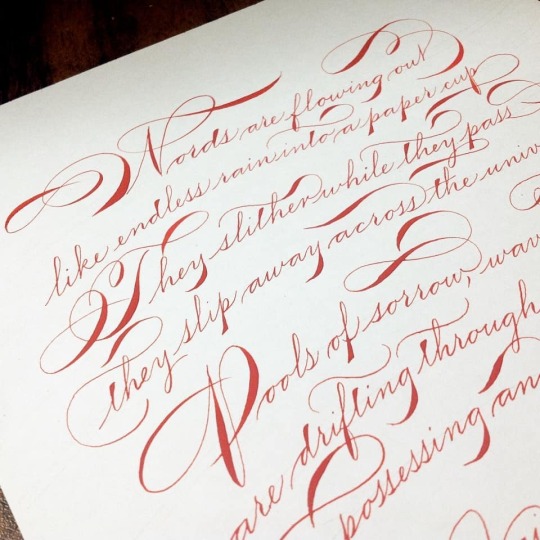

Across the pond, Americans had a different idea about what it meant to be a tutored gentleman. In the early 1800s, no more than a few decades after the revolutionary war, the newly independent United States was buzzing with change and eager for fresh ideas. At the time, the standard for written correspondence still took after English traditions. “A strictly uniform and consistent order of writing, it required stiff muscular and emotional restriction, allowing for almost no individual expression, and very little room for either artistic or personal style,” Tona Bell writes of Spencerian history at The Paper Seahorse. “It almost seemed symptomatic of the grievances Americans felt before declaring their independence from Great Britain.”

Enter Platt Rogers Spencer, a reformed alcoholic turned religious teetotaler who invented the baseline for American penmanship at the remarkably young age of 13. Not only did this boy develop one of the most dynamic penmanship styles known to man, but he also had a beautiful philosophy and even theology behind his writing style. Spencer believed that God, the originator of all beauty, could be seen in nature. So if he could express the fluid lines of the streams flowing by his house, the gentle wheat blowing in the wind, and the cumulus clouds rolling over mountain peaks through his penmanship, then he would be both paying tribute to and expressing the beauty of God.

Of course, it didn’t take long for Spencerian script to be a way for people to demarcate social rank. Those tutored in the style were considered more respectable. Those who wrote in a way that was less polished were looked upon with suspicion. Like those dirty unwashed masses with boots unlaced and waistcoats unbuttoned, the wrong wave of a pen could suggest moral laziness and even criminality. For legendary stories about men with exquisite handwriting, look up Francis B. Courtney, who was known to his peers as “The Pen Wizard.” It’s said that, whenever he taught, he’d fill a chalkboard with a masterful script replete with flourishes. At the end, he’d take a piece of chalk in each hand and sign his name simultaneously in opposite directions, as though he were conducting an orchestra.

The thing about Spencerian script is that very few people know how to write like this today. For one, you need specialized tools — the right kind of pen and paper, which have almost all but disappeared from the market unless you know where to turn. You also have to retrain your body. When writing, most people plant their hand on the table and move the pen using a series of finger movements. This puts stress on our fingers, which results in writer’s cramp. Spencerian writing requires you to hold the pen at about 45 degrees, knuckles up towards the ceiling, and use muscular movements at the wrist and arm. Learning how to write with your whole arm and not just your fingers takes years of proper training and practice. Whenever I see someone suggest that the decline of suits represents a decline in civility, I wonder how they write. In all likelihood, a hundred and fifty years ago, their penmanship would mark them as being part of the criminal class.

Virtue has little, if any, relationship to how we dress. It can also be judged directly. While notions of virtuousness are sometimes culturally dependent, certain themes emerge across time and space. We admire people who exhibit courage, kindness, patience, humility, temperance, diligence, and a charitable spirit. To be virtuous is to treat those who are less fortunate with compassion, to have a sense of justice, and to be sincere. That may include dressing a certain way, such as showing up to a wedding in a sober suit when the dress code requires. But I’ve also been impressed by the different ways people choose to respect ceremonies — funerals that include cheerful attire because that’s what the deceased would have wanted, or sneakerheads who get married in their favorite sneakers and ask their groomsmen to wear the same.

A better and more succinct summation of this idea can be found in Fela Kuti’s 1973 Afrobeat classic, “Gentleman.” In an irresistible African pop song, Kuti points out the colonial mentality of Africans who conflate European customs with civility. He also sings about the irony of a “colonial gentleman,” noting that he’ll never be a gentleman himself. The final verse addresses clothing, in Nigerian Pidgin English:

I no be gentleman at all o

I be Africa man original

I no be gentleman at all o

I be Africa man original

I no be gentleman at all o

I be Africa man original

Africa hot, I like am so

I know what to wear, but my friends don’t know

Him put him socks, him put him shoe

Him put him pant, him put him singlet

Him put him trouser, him put him shirt

Him put him tie, him put him coat

Him come cover all with him hat

Him be gentleman, him go sweat, all over

Him go faint right down, him go smell like shit

Him go piss for body, him no go know

Me I no be gentleman like that

Of course, this isn’t to say that suits and sport coats aren’t wonderful things. I wear a sport coat about half the week. It’s just to say that clothes have little to do with civility or virtue, and to judge someone based on their clothes is to be unvirtuous by definition.