Woe betides anyone who takes life advice from me. I am, after all, a man who wound up writing about workwear on a blog called Die, Workwear. But for the academically inclined who may be hustling to get grad school applications submitted before December 1st, let me impart some advice: don’t go to grad school. Get a turtleneck instead.

A turtleneck will confer you all the same benefits of having a graduate school education. For one, you’ll feel smugly superior to other people and have false confidence that you’ve become more attractive (you are not, and you have not). You get to say “residency” with a convincing and assured tone. You’ll fit right into any event billed as being part of a “speaker series.” Like having a graduate diploma, a turtleneck will not increase your job prospects. You will, however, become slightly more annoying to everyone around you. Consequently, you will likely suffer from incurable loneliness and social isolation. The only difference is that graduate education can cost you upwards of a quarter-million dollars. To put that in perspective, that’s like buying 5,000 turtlenecks from J. Crew or three from Cucinelli.

How did this workwear garment become such a symbol of the smug and insufferable? The story of the turtleneck follows the same arc of almost everything associated with high-society. Things that once gave more than a whiff of moral laxity are today used as a cudgel against rebellious youths. At the turn of the 20th century, proper gentlemen in frock coats frowned up upon lounge suits as the ill-attire of workwear men and lowly store clerks. Today, a suit-and-tie is seen as the entry card to proper society. Similarly, jazz was once labeled as the “devil’s music” for its focus on improvisation over a traditional structure, performer over composer, and the black experience over conventional white sensibilities. Now it’s something people list on their Facebook profile to seem high-class and sophisticated. (Anyone who thinks rap music represents some kind of new degeneracy needs to listen more closely to blues classics such as Victoria Spivey’s “Dope Head Blues” and Charley Patton’s “Spoonful Blues”).

The turtleneck, called a “roll neck” by some Brits, follows the same storyline. There was a time when this high-neck style was associated with drunken fishermen and longshoremen working in and around the North Sea. This heavily scoured pullover, often made in a natural cream-colored woolen yarn, was a favorite of sea dogs because it protected bare necks from the salty air. Over time, other men took up the sweater for its practical advantages.

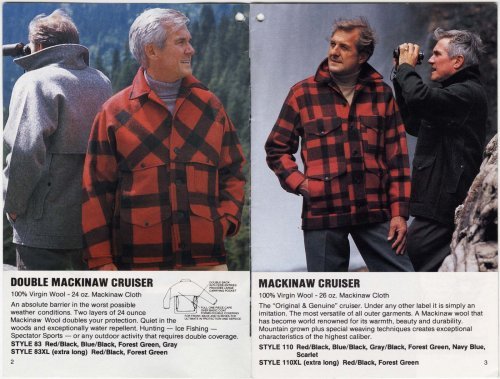

“In the 1880s, [the turtleneck] was associated with the fad for bicycling, tennis, yachting, and polo,” Bruce Boyer wrote of the sweater in True Style: The History and Principles of Classic Menswear. “The Saturday Evening Post, American’s most popular magazine in the early years of the twentieth century, was fond of showing handsome, square-jawed college students in sporting gear on their covers, like the J.C. Leyendecker drawings of Harvard oarsmen wearing thick-ribbed turtleneck letter sweaters in college colors. An example of the scholar-sportsmen. […] Many World War II sailors who fought the Battle of the North Atlantic were terribly glad for their thick wool turtlenecks, watch caps, and thick peacoats during long, dark, penetratingly cold nights on the deck. We see them in our memory’s eye at the rail, the dark top of the sweater peeking out from the peacoat, binoculars slung ‘round the neck.”

It’s said that the playwright Noël Coward started the fashion for turtlenecks in 1924, but even he took the style from the “seedier West End chorus boys.” In a diary entry written the same year, Evelyn Waugh recounted seeing the “new sort of jumper” at a party in central Oxford, England, which further brought the sweater out of its working-class origins. Waugh judged it to be “most convenient for lechery because it dispenses with all unromantic gadgets like studs and ties.” Further, it has the practical effect of hiding the “boils with which most of the young men seem to have encrusted their necks.’’

It’s somewhere in that mix of workwear and high-society where the turtleneck became associated with effete intellectuals. In the immediate post-war years, French existentialists, New Left academics, and bohemians started wearing the style to show solidarity with blue-collar workers. In the US, college students layered turtlenecks under their military surplus duffle coats. At the clubs and cafes around Paris’ Left Bank, where a confluence of politics, philosophy, and literature emerged from the wreckage of the Second World War, men such as Jean-Paul Sartre, Albert Camus, and Samuel Beckett wore turtlenecks under overcoats and leather jackets. In Britain, “angry young men at redbrick universities” wore baggy turtlenecks with wide-waled cords and thick brogues. “The outfit was intended to show rebellion against the conservative power structure represented by a tailored wardrobe of a dark suit, white shirt, and club tie,” Boyer notes.

A generation later, the turtleneck has lost much of its workwear and counter-cultural edge. The same people who picked up suits and jazz music to seem sophisticated now wear turtlenecks to affect the look of those post-war, anti-establishment intellectuals (who, to be sure, were affecting the look of workmen). The turtleneck is the knitwear version of Reply Guy. It’s the “well, actually” of sweaters. The Cut’s Emilia Petrarca believes it makes for a great first-date outfit for women (“They’re soft and clingy and warm, and they keep you snug emotionally, too”). But when asked how she feels about turtlenecks on men, she hesitates. “Sometimes men look like dinguses in turtlenecks,” she admits. “If worn with round glasses and a copy of Foucault, a turt can make a man look like a liberal arts freshman. If worn with jeans and New Balance, he drank the Silicon Valley Kool-Aid and probably wants to talk to you about the Bitcoin bubble. It’s just so easy to fall for a stereotype.”

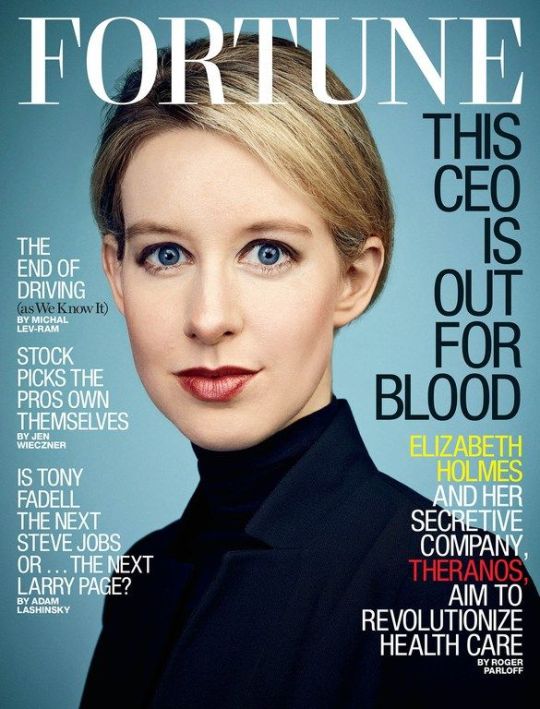

The style may even be dead for women. In an article at The New York Times, Vanessa Friedman wonders if black turtlenecks will ever be looked at in quite the same way again after the rise and fall of Elizabeth Holmes.

When it came to her turtlenecks, Ms. Holmes told Glamour in a 2015 interview, just before things started to go south, that she had “about 150 of them” and had been wearing them since she was 8. It was presented as a default choice, but the irony is that it had the effect of making her instantly recognizable — just as Mr. Jobs was, in his black turtlenecks. It conveyed, despite the caveats, discipline and rigor, not laziness. […] But such an individual uniform has a risk if you don’t live up to the promise. In the end, it’s the substance behind the style that makes the difference; what you wear becomes its expression. So already, what was once the symbol of her dedication has become the symbol of the backlash, as the revisionism has begun, with various columnists berating themselves for not “looking behind the black turtleneck.”

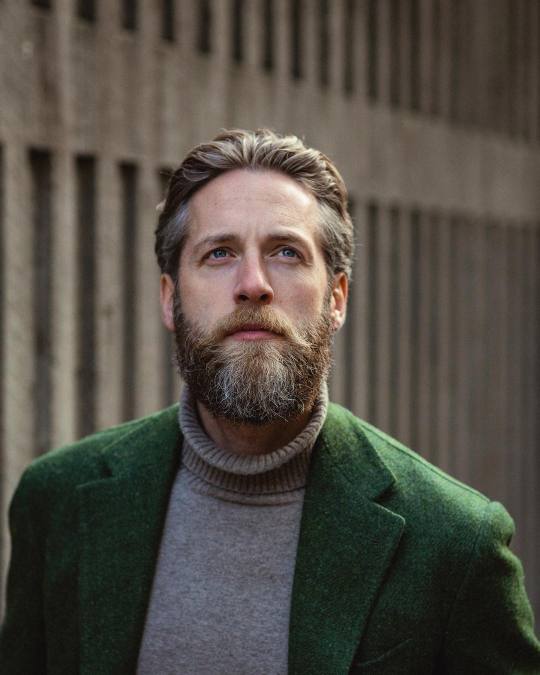

The turtleneck today is a statement sweater and comes pre-loaded with history. But as Friedman notes, it’s the “substance behind the style that makes the difference.” Just because pretentious people like suits, jazz, and whiskey, doesn’t mean you have to abandon such things. The best way to reclaim the turtleneck is to wear one without any pretense. It’s a comfortable sweater with admirable workwear roots, looks handsome with casualwear or tailoring, and throws your face into high relief. If you don’t want to look like a dingus in a turtleneck, don’t abandon the sweater – just don’t be a dingus.

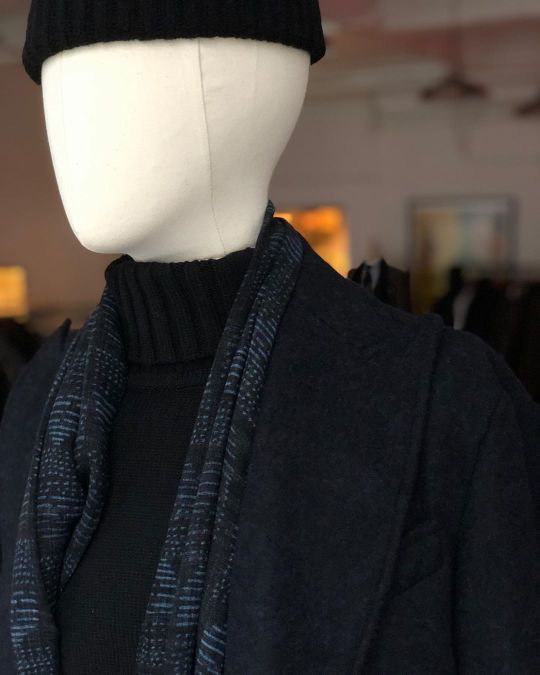

My friend Pete in San Francisco wears them especially well. “A turtleneck is the sweater equivalent of a collared shirt; it frames your face,” he says. “Once you think of it that way, it’s easy to see ways to pair one. Bulky Arans or other thick knits go naturally with stout outerwear, such as a Melton topcoat or plaid Ulster. Smaller-gauge ones look fantastic with casual suits, and you can’t beat a beefy navy or grey turtleneck with a pair of jeans. I like the practicality of turtlenecks. When it’s cold, you could pop on a crewneck and scarf, but a turtleneck is both. When the fog rolls through the Golden Gate Bridge, a stout turtleneck and tweed Balmacaan keep the wind and cold at bay. ”

I generally find chunky turtlenecks to be more versatile, particularly in staple knitwear colors such as cream, navy, and grey. They go well with certain kinds of coats – a topcoat with a collar popped from the back. or a sherpa trimmed bomber. “Chunky certainly has a Maine Guy attitude, while thin will get you closer to that bohemian, intelligentsia energy,” says GQ Style writer Rachel Tashjian. On the downside, since a turtleneck is basically a sweater with a built-in scarf, a thick one can wear uncomfortably hot once you’re indoors. Bruce Boyer, who’s much more sensible than me, prefers thinner versions. “The chunky ones, the Aran sweaters et al., look very broth-of-the-heather. But they work better on an open boat in the North Atlantic; you can’t wear them indoors with central heating. Today most buildings are overheated.”

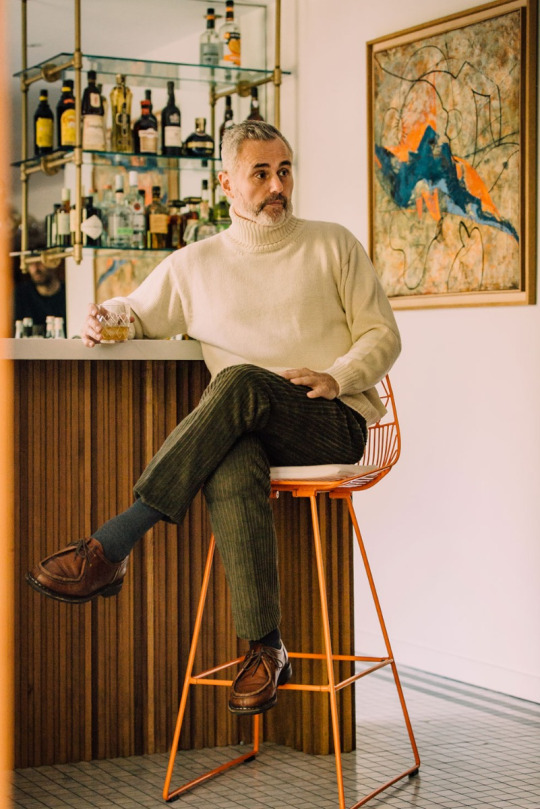

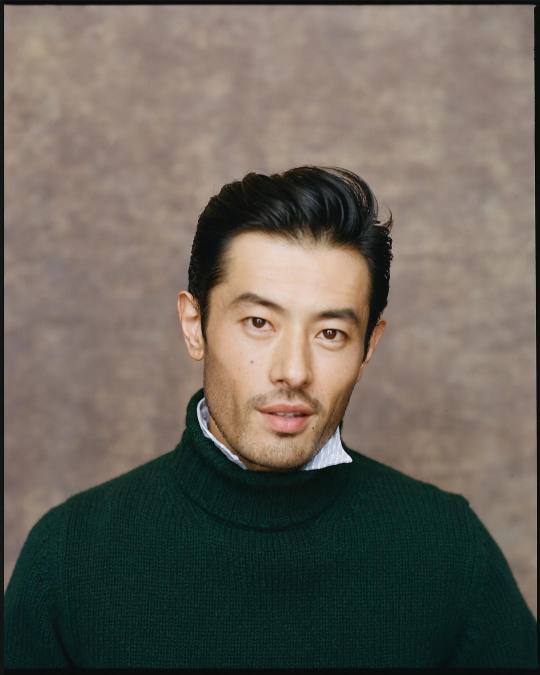

Mark Cho of The Armoury says he likes to wear thinner versions doubled down at the neck. “I like to roll mine as far as I can, to the point where I’m doubling over the turtleneck, and it almost looks like a mock neck. I wear them with a shirt, such that the collar is peeking out a bit, but not so much that the collar points are popping out.” His store sells cashmere versions in a variety of colors, from mossy green to a smart navy. “They’re just the right weight to always be comfortable.”

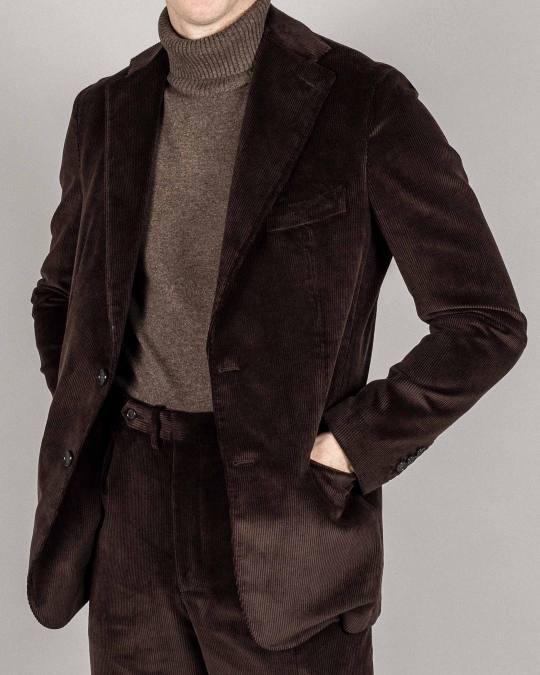

Pete says he finds occasions for all designs. “I love chunky turtlenecks, especially those utilizing different weaves, such as cable knits,” Peter continues. “The visual and tactile interest makes a cozy sweater that much more enjoyable to wear. I have thinner ones too, but I usually reserve them for casual suits, like corduroy or flannel. It’s less dressy than a tie, but not as casual as a crewneck. Jersey turtlenecks are great under a chamois shirt and barn coat.”

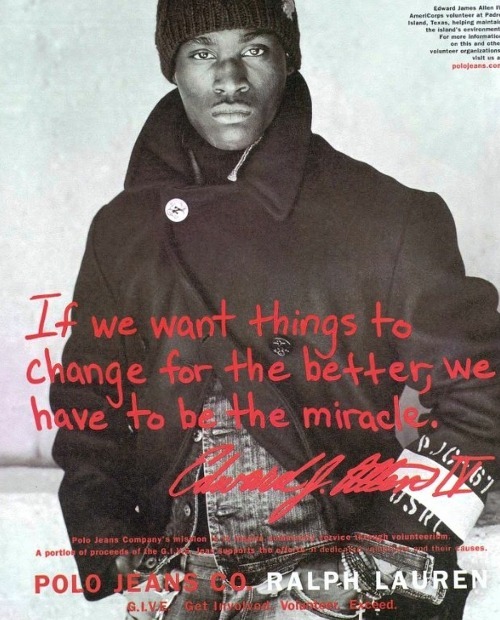

If you can only own one, I would start with a chunky cream turtleneck, which is reasonably versatile unless you run relatively warm. You can find those at The Armoury, Berg & Berg, Orvis, De Bonne Facture, and Trunk Clothiers. Other colors can be had through Drake’s (racing green), Man 1924 (goldenrod), Margaret Howell (olive-brown), Rubato (soft fawn), and Ralph Lauren (pitch black). For something textured, Doppiaa and Howlin by Morrison have gently brushed turtlenecks this season. Proper Cloth has tasty Donegal Arans, which have colorful flecks and beautiful cabling. Andersen-Andersen, SNS Herning, and North Sea Clothing are good if you want something that looks at home in a submarine.

No Man Walks Alone, a sponsor on this site, also just dropped a fantastic lookbook, where they showcase their Inis Meain and Chamula offerings. Pete says the one from Chamula, which features a monstrous collar and hand-knit cabled pattern, is among his favorites. “It has different weaves on the front and back. The way it’s pieced together, you can actually wear it either way. I’m also partial to a stocky Aran from Inis Meain. I wear it with jeans and a Donegal sport coat for the cool weather.”

For a thinner turtleneck that you can layer under trim tailoring, it would be hard to beat John Smedley, a standard-bearer for this sort of thing. Todd Snyder also has a very handsome ochre knit this season. If instead, your wardrobe leans a little more contemporary and directional, perhaps with labels such as Lemaire or Stephan Schneider, you may be better served by these double-faced jersey turtlenecks from the Japanese label ts(s). No Man Walks Alone and Namu Shop, both sponsors on this site, offer them in a variety of colors. For something that won’t break the bank, check-in with J. Crew and Uniqlo. J. Crew has an attractive jacquard stripe this season, along with a reissue of their 1988 cotton rollneck.

Finally, here’s the other parallel between a grad school diploma and a turtleneck: no one cares if you have one. If, however, you feel self-conscious at any point, just pull the high-collar up and over your head. A turtleneck is perfect for soothing anxious introverts.