Anderson .Paak’s fire engine red sunglasses beamed like a lighthouse when he covered Lil Nas X’ “Old Town Road” on BBC Radio 1 earlier this week. Paak’s cover brought a country-inspired rap song into neo-soul, making this a triple fusion in terms of music genres. And while the room was only dimly lit, he may as well have had ten spotlights on him. In the nearly pitch-black room, it was hard not to notice his safety yellow tracksuit and ‘90s-era sunglasses (oh, and his music was amazing as well).

.Paak’s ensemble beautifully demonstrates the power — and more importantly, joy — of dressing for self-expression, rather than out of fear of getting things wrong. While getting some sunglasses filled with prescription lenses yesterday, I noticed my local optometry center was filled with the same eyewear options: rectangular, mostly minimalist, and above all, inoffensive. There’s nothing wrong with subtle eyewear, of course, but does the world need more versions of the same frame?

Forget dressing for your body type. Dress for your personality or, better yet, dress for fun. A pair of distinctive frames can underscore the stylistic references in an outfit — the mid-century modernism of a slim-lapeled suit or the sleazy 1970s style of slim jeans with a leather jacket. Notably, many of the best-dressed men wear frames as a style signature. Think of David Hockney in his thick, coke-bottle glasses, or the different styles Michael Caine cycled through as an icon of English cool. Even Bruce Boyer — a measure of good taste, if there ever was one — doesn’t just wear his P3s in black or brown. He wears them in spotted blonde tortoiseshell. Here are five eyewear brands with some personality if you’re open to trying something new.

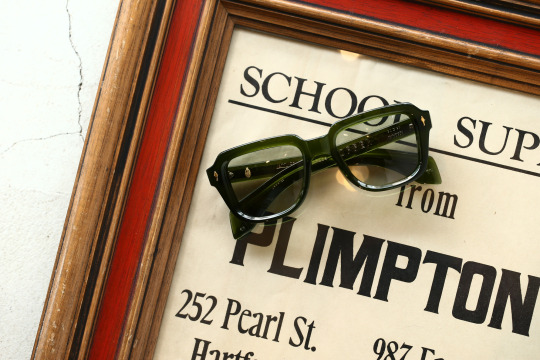

Jacques Marie Mage

The freeway is a favorite metaphor of writers trying to describe Los Angeles’ socio-economic divides. In his book City of Quartz, urban theorist and historian Mike Davis chronicles some of Los Angeles’ more intractable problems: the isolated communities, smashed labor movement, and corrupt politics. On one side of the county, you have working-class immigrants, Latinos, and African-Americans. On the other side resides the wealthy one-percenters who shop at Rodeo Drive. For the most part, these communities rarely interact with each other.

At the same time, this Balkanization has led to some unique, home-grown cultural movements. Los Angeles is home to Hollyweirdos, Chicano car culture, straightedge scenes, vintage fashion obsessives, and some great music. The now-defunct Good Life Cafe, a Crenshaw Boulevard health food market turned open-mic venue at night, helped launch many influential Black music acts in the 1990s.

Jerome Jacques, a French-born designer who moved to Los Angeles about 20 years ago, has taken some of these influences and created an eyewear label that feels distinctively Angeleno. He says his company, Jacques Marie Mage, is an amalgamation of his interests in bygone areas — from Brutalist architecture to the Napoleonic Empire. One of his collections was inspired by Bob Dylan’s life and music. Other editions are inspired by the mystique of Olympia Mancini, the 17th-century aristocrat known as much for her irresistible charm as her penchant for plotting murder. In collaboration with Hopper Goods, Jacques designed a pair of chunky frames modeled after something Dennis Hopper wore in the acclaimed film Easy Rider.

Jacques Marie Mage’s collections are also united by some common themes. Their frames have bold geometric shapes that recall the idealism and decadence of the 1960s and ’70s. Each pair is decorated with a signature arrowhead front pin and three spur-shaped stars on the sides. But it’s done a way you’d only ever see from a Los Angeles brand (that is, it looks kind of chintzy, but also kind of cool). There’s something about them that feels swarthy, exuberant, and inscrutable. These are the sassy frames a woman would hide behind in an empty LA diner. Or a retro-styled man would wear at The Dresden Room, one of my favorite LA lounges (also where the 1996 film Swingers was shot).

I remember buying my first pair, their collaboration with Hopper Goods, and feeling dizzy from sticker shock. Jacques Marie Mage’s frames run anywhere from $450 to $1,000, depending on where you shop, and they never go on sale (most hover around $600). But over the last year or so, I’ve acquired two more — their 1950s styled Jules, which feel vaguely Michael Caine-esque, and newly released Hickock in translucent taupe. These thick, oversized frames complement workwear, particularly Western-inspired labels such as RRL and Visvim, and they look even better with leather jackets. They’re distinctive but surprisingly easy to wear, and have the kind of sleaziness Ray Liotta sported towards the end of Goodfellas (again, very much an LA style). At a recent trunk show, one of their reps told me their most popular model for men is their angular shaped Mollino.

Dita

Jeff Solorio and John Juniper grew up in Laguna Beach, surfing along the Pacific Coast and snowboarding around California’s San Bernadino mountains. Sometime in the mid-90s, the two longtime friends co-founded their own luxury eyewear brand, Dita, which now has flagship stores around the country. Like Jacques Marie Mage, their frames are made in Japan and inspired by 1950s through ’80s eyewear design.

“Surfing and snowboarding were big things for us. From those interests, we identified a need in the market,” says Juniper. “It started with a few female board sports athletes we knew. [They wanted] sunglasses that performed, but that they could wear anytime. Even then, the frames we were interested in making pulled from more classic shapes from the past — oversized, iconic designs from the ’50s and some ’80s punk rock influences.”

Dita is like a futuristic version of Cazel, the West German eyewear brand that was hotly popular with youths in the 1980s (“Somehow the rap game reminds me of the crack game/ Used to sport Bally’s and Cazals with black frames,” Nas rapped on “Represent”). For a time, wearing a pair of Cazels could get you snatched, much like wearing an untucked gold chain or rare pair of Nikes. Dita’s don’t have the same street cred today, but their squarish frames and gold accents have a lot of that 1980s vibe.

I love their designs and construction. Their weightless, featherlight line is much more comfortable than Jacques Marie Mage’s heavy plastic pieces. Certain models, such as their System One (one of my favorites in their collection), have uniquely designed metal wires, which make both the front facade and sidearms. The company also has an “Asian fit” line for people like me, who struggle to find something that fits comfortably on the nose. Some of these designs can be a bit “muscle tee guy in Las Vegas.” But you can avoid the worst stereotypes by wearing these with rancher jackets instead of Affliction tees.

Masahiro Maruyama

In the fields of philosophy and experimental social sciences, there’s a neverending debate about whether beauty is purely subjective. Some studies show that — across genders, societies, and age groups — people admire certain facial features: youthfulness, symmetry, clarity, and vivid color. At the same time, since we all live in a society, it’s hard to separate these preferences from our cultural influences. Do beauty ads show these things because we like them? Or do we like them because we see certain beauty ads?

In 2008, a team of computer scientists from Tel Aviv University ran 125 portraits through a “beautification engine,” which was a computer-generated version of “hot or not.” The before-and-after photos showed how different people could look if they had more symmetrical faces. Unlike the digital retouching done for fashion magazines, wrinkles were not smoothed, and hair color was not changed. For most faces, the changes were very subtle — nearly imperceptible. Their faces simply became more symmetrical, like flattering Tudor portraits.

Unsurprisingly, reviews were mixed. While some saw the results are more beautiful, others were skeptical. “Character can be lost. A blandness can set in. The quirky may become plain,” Sarah Kershaw wrote of the study in The New York Times. “Irregular beauty is the real beauty,” added Lois Banner, a historian who studies changing beauty standards. Attempts to measure beauty often results in the tyranny of sameness, making everyone look alike. Yohji Yamamoto said it best: “I think perfection is ugly.”

Masahiro Maruyama, a Japanese eyewear designer, is all about imperfection and asymmetry. His frames remind me of Kintsugi, meaning golden joinery, which is a Japanese technique for repairing broken ceramics with gold to give them a new life. The idea here is that something is beautiful not despite its imperfection but because of it – a sharp difference between Japanese and Western aesthetic philosophies. “Masahiro believes there shouldn’t be symmetry in eyewear because our faces aren’t symmetrical,” says Kiya Babzani of Self Edge, who carries the line at his stores. “Everything from the temples to the bridges to the way the lenses are cut is fluid and asymmetrical.”

Whereas most frames today are manufactured by Luxottica in Italy, Maruyama’s frames are made by hand in Japan. Once cut, the frames are sanded down and smoothed by hand, rather than by using a motorized sander. Some frames are also hand-painted, rather than machine sprayed, to give them a distinct look and finish. “He doesn’t use a computer to design his frames, which is unheard of in 2019,” adds Kiya. “Nowadays, almost everything is sketched onto paper and then scanned into a machine so that they can be precisely cut.”

On-screen, the frames can look intimidating, but they’re much more subtle in real life. You barely notice the two-tone accents or uneven edges. They look fun and creative, and show you have a sense of humor about yourself. They’re also one of the few frames here that, I think, can be worn across a broader range of wardrobes. They sit naturally with the kind of stuff sold at Self Edge, such as raw denim worn with heavy plaid flannels and bomber jackets. But they’re also at home with off-beat Japanese workwear, such as Engineered Garments, and soft tailoring.

Buddy Optical

Most frames on this list are thick and often pair better with workwear than anything contemporary. If you’re looking for a refined, thin frame look, Buddy Optical in Japan has just the right touch of vintage without being retro. The company takes its name from Buddy Holly, but their frames are more like something I’d imagine a Belgian architect might wear in mid-century rooms. These frames go well with labels such as Lemaire, Margaret Howell, and Stephan Schneider.

Thin wireframes are more than an aesthetic. I find they’re often more comfortable than their thick plastic counterparts. The arms are forgiving, the glasses are nearly weightless, and the frames sit better behind the ears. One of my most worn pairs is Garrett Leight’s Paloma, a wirey, nearly rimless design that’s so comfortable, I often struggle to wear something else.

Buddy Optical’s frames are inoffensive, like many minimalist eyewear designs, but they’re not without personality. Their “a” frames have a wide, octagonal shape reminiscent of vintage French styles. The Emory is a sleek, brushed metal option that reminds me of the aerodynamic shapes seen in Pan Am-era designs. For the mild-mannered and conservative, the Sorbonne is an update on the mid-century P3 — a style closely associated with trad and Ivy. They have what Bruce Boyer once called “the hallmark simplicity of their shape, sentimental references to callow youth, and just a whiff of bookish charm.” You can find them at Namu Shop, a sponsor on this site.

Birth Control Glasses

Now that I’ve lured you this far into the post, I’ll recommend frames so hideous, they’re colloquially known as Birth Control Glasses. For decades, these were standard issue in the US military, often first given to boot camp personnel. The tradition roots back to the Second World War, when the US government — who, at the time, was frantically trying to recruit enough soldiers to fight in Europe and the Pacific — enlisted a ton of men with bad eyesight. In 1941, a US lieutenant complained that 75 men under his charge broke their glasses and couldn’t afford to buy new ones. A month later, “the Surgeon General, the Medical Department, was directed to provide spectacles, repairs, and replacements to all military personnel needing them.”

The first US Army glasses were made from metal, but after the war, the government switched to cellulose acetate (the plastic found in most frames today). Initially, these cheap plastic frames went from being silver-colored to black, but by the mid-1970s, someone decided they should be muddy brown – almost like the color of diarrhea.

For decades, libidinous service members derided these thick, magnifying frames as Birth Control Glasses because they effectively reduced their chances of procreating to nearly zero. Violently shedding these frames was a rite of passage for the men and women who graduated from boot camp. In 2012, the Department of Defense realized their frames were so hated, they updated them to the sleeker all-black 5A (a squarish structure similar to what you’ll see at every Lenscrafters).

But BCGs are also beloved by certain eyewear companies. Lowercase and Knickerbocker collaborated to make their own version last year. Mohawk General Store recently put up a selection of them with polarized lenses (theirs are pictured above). In a way, these frames check many of the boxes on the “coveted menswear” bingo card: they have a deep history, come with military provenance, and are deadstock. I don’t think they work well as regular eyewear, but their oversized scale lends them well to sunglasses. You can find them on eBay and Etsy for as little as $20 (although, sizing is a bit iffy). They’ll probably reduce your chances of getting laid. But if you’re out here talking about the virtues of raw denim and Goodyear welting, you, like me, already have Birth Control Hobbies.