About fifteen years ago, some friends and I took a train to go shopping in San Francisco. One of my friends had just been invited to a wedding, and while we were all graduate students at the time and had very little money, she was determined to buy something beautiful for the occasion. So we headed downtown to Barneys.

Until then, I had never been to Barneys. I remember walking into the building and feeling overwhelmed by the store’s expansiveness and glossy emporium feel. There are six main floors for men’s and women’s collections. Each floor is neatly arranged but also packed with the kind of clothes, bags, and perfumes that most people have only heard of through magazines. Menswear is on the two top-most floors: there’s one for designer and another for tailoring. Here, you’ll find racks of Italian sport coats made from plush cashmere-blend hopsacks and silky windowpane patterns. There are dolefully constructed Rick Owens leather jackets and Thom Browne sweatsuits that are so expensive, they suggest you loot your own country. Near the rows of crystal-weave Charvet ties are the European-made leather bags, which I imagine are sold to men who jet around the world. The whole store felt very glamorous.

Two weeks ago, Barneys filed for Chapter 11 bankruptcy. They announced that they’ll be closing all but five of their 22 locations — the San Francisco store being one of the few that will be spared, along with their Madison Avenue flagship and the Chelsea store that opened three years ago around the block from their original location. If Barneys shutters, it will be the highest-profile victim of the current retail downturn. Some blame the company’s woes on online competition and skyrocketing rents (their Madison Avenue store’s rent nearly doubled to $30 million in January, which the company cited as a significant reason for their bankruptcy). But I can’t help but wonder this isn’t a sign that the once blinding and wonderous shine of glamour is starting to dull.

View this post on Instagram

Glamour should not be confused with style or beauty. Traits such as elegance and charm are things that people possess, but glamour is something that people perceive. The word is not, as you may have assumed, French in origin, even though Paris has had a particular draw for the glamour obsessed since the 18th century. Instead, like Harris Tweed and malt whisky, glamour is originally Scottish. In the early 20th century, it referred to a literal magic spell — someone had glamour, or they cast glamour. Glamour was associated with Celtic magic, gypsies, and witches. It was a deception cast over someone’s eyes.

During the Golden Age of Hollywood, glamour came to take on more positive connotations. Glamour is about the sultry starlets of the period, including Gloria Swanson, Greta Garbo, and Joan Crawford. There are glamourous men, as well, such as Clark Gable, Gary Cooper, and Cary Grant. The modern usage of the term “coincides with the rise of the ‘society of the spectacle,’ to borrow the French theorist Guy Debord’s term — the congregation of masses of people in urban centers, alongside a burgeoning news media spreading images and ideas, and a proliferation of luxury goods made possible by a newly industrial society,” Leslie Camhi wrote of it in The New York Times.

John Berger, the art critic who wrote the influential feminist text Ways of Seeing, characterizes glamour as being the product of social envy. “The power of the glamorous resides in their supposed happiness,” he once said. “This state of being envied is what constitutes glamour, and publicity is the process of manufacturing glamour. Glamour is supposed to go deeper than looks, but it depends upon them, utterly.” Cultural historian Stephen Gundle agrees. Glamour for him is an opium for the masses, a way to present the escapist fantasy of social mobility.

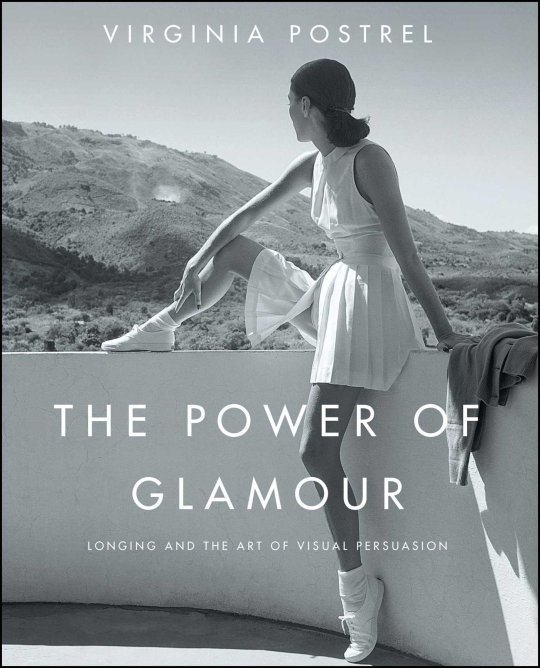

Virginia Postrel, the author of The Power of Glamour, is more sanguine. Glamour is certainly escapist, she writes, but it doesn’t dull the senses like wine. Instead, for better or worse, it intensifies longing, fosters hope, and stokes ambition. As Andrew Carnegie put it, “capitalism is about turning luxuries into necessities.” For Postrel, that’s glamour — delusively mysterious, alluring, and glorifying. It’s a process of image-making and idealization that allows us to transcend the banality of everyday life.

“Most importantly, for Postrel, glamour is an illusion ‘known to be false but felt to be true’ — a deceptive image of grace springing from an ’emotionally authentic’ longing,” Camhi summarizes. In this sense, glamour is something that’s just a little outside of your reach. Neither God not everyday people can be glamorous, only those who we think we can one day be. Translucence is glamourous — crystal barware and stained glass windows — because they conceal and reveal at the same time. They invite us into a world but don’t give us a completely clear view.

Barneys wasn’t just cool; it captured the glamorous lifestyle of downtown New Yorker sophisticates. GQ style writer Rachel Tashjian described it as being “between Studio 54 and Soho House. Luxurious, with a big personality. Maybe even a little dangerous. It was a place to see and be seen, where Cher and Basquiat hunted for Armani tailoring and clingy Gaultier mesh. Andy Warhol starred in the company’s print ads, and Glenn O’Brien was its advertising director, commissioning wry and charming Jean-Philippe Delhomme illustrations. It was enough of a scene-maker that book parties were held there, attended by the likes of Dominick Dunne and Norman Mailer.”

This narrative, of course, is the making of a glamorous mirage. Most of the people who actually shop at Barneys are remarkably ordinary. Like many retailers today, Barneys was born from an ethos that shopping is an act of self-actualization. You didn’t just go to Barneys to feel rich or cool. You went to indulge in the fantasy that you can become a certain kind of downtown New Yorker: uncompromised, independently wealthy, self-assured, inspired, and composed. Barneys is for guys who fancy themselves to be like Richard Gere or John F. Kennedy Jr.

This is what other writers miss when they write about Barneys. There are lots of cool, artsy, and mysterious stores that allow us to shop according to our aspirations (fashion is mostly aspirational anyway). Supreme is cool and Totokaelo is mysterious. But neither of them is glamorous like Barneys or Ralph Lauren’s Polo Mansion.

Somewhere along the way, Barneys got knocked off its perfectly buffed onyx pedestal. In 2012, Cathy Horyn, then The New York Times’ fashion critic, wrote a profile on Barneys and the company’s new owner, a billionaire and former hedge fund manager named Richard Perry. “Critics complained that Barneys was now merely offering the traditional menu of the globalized mercantile world, with its buffet of high-margin shoes and bags,” she wrote. “Among the descriptions I heard were that the new Barneys looked like a mall or a duty-free shop. ‘It looks like Macy’s but a bit more high-end,’ Ronnie Cooke Newhouse, creative director at Barneys in the early ’90s, told me, adding, ‘It’s so out of step with where things are going.’”

What once felt languid now looked lurid. The “sea of bags” didn’t suggest opulence, but rather a lack of editing and taste. There was a time when Barneys was unabashedly elitist and proudly exclusionary — you were part of the fashionable cognizati or you weren’t — but now that arrogance started to chafe. Meanwhile, the company’s warehouse sales, which were held at downtown outlets, began to chip away at the veneer. And for people like me, who initially shopped there because they wanted to live a particular dream, going to the store just increasingly felt routine. Saying hello to your sales associate didn’t make you feel any more like the fancy man in those old black and white movies. It was merely your regular and unadorned life. The clothes, in the end, weren’t transformative. The promise of self-actualization never materialized.

Perhaps Barneys is closing because of online competition, high real estate costs, and mismanagement — only the executives behind the company can say. But as someone who stopped shopping at Barneys many years ago, I wonder if the age of authenticity hasn’t just killed glamour in all of its forms. When I think of my style interests, glamour has little relevance or appeal. Bruce Boyer, for example, has written admiringly of Gary Cooper — a glamorous man, if there ever was one. But ironically, I find Bruce’s style to be more inspirational than Cooper’s. I also don’t look to James Bond of Cary Grant for direction. They’re too lofty. Instead, I look to people I know and can email.

Similarly, glossy fashion magazines have been replaced by street style sites, Instagram influencers, and independent blogs (who, admittedly, stage photos in their own ways). Whereas I used to shop for preppy clothes at Ralph Lauren — mostly because of the glamour — my money now goes towards smaller and “more authentic” trad shops such as O’Connell’s. Boutique retailers such as No Man Walks Alone and Self Edge are many things, but they are not glamorous. Instead, they offer a high level of personalized service, specialized product knowledge, and uniquely “authentic” products. Glamour still matters for most consumers, but for many, it’s considered to be a bit “basic.”

To be sure, authenticity has its own illusions, but it’s distinct from glamour in that it tries to get at the truth. Glamour, on the other hand, is about transcending reality (by its nature since it’s about escapism). In an old 1936 issue of Apparel Arts, the editors detailed their ideal menswear shopping space — a glamorous six-story building with a basement lounge and rooftop restaurant. This “Permanent Modern” layout was supposed to be an enduring concept for retailing, but such massive commercial complexes feel so archaic now. For many men, including me, places such as Saks Fifth Avenue and Neiman Marcus feel too impersonal to be authentic. It’s the difference between getting dinner at California Pizza Kitchen and your local mom-and-pop restaurant.

Tashjian recently spoke to Gene Pressman, the grandson of Barney Pressman, the company’s founder, for a story at GQ. Gene is credited with transforming the family’s company from a discount menswear store in the 1970s into a small beacon of savvy luxury. He’s been out of the retail game for about fifteen years, but still thinks about it constantly. When asked why he thinks Barneys is struggling, he dismissed the internet. “I know retailers like to blame it on the internet, but that’s like back in the day, if I were to blame it on the weather. It’s relevant, but not that relevant.” The real reason, he said, is simpler and sadder. “They just stopped being relevant.” Tashjian continues:

The bankruptcy filing is surely due in part to the rise of online shopping, but Pressman pointed out that people still go to the theatre, and they still go to concerts. They might love going to restaurants more than ever before. Retail is no different, he said: ‘There has to be a reason for someone to go. It has to be an experience, and it has to be fun. It has to be interesting. It has to be different. Barneys was a great form of entertainment. That’s how I always viewed it: that you’re creating theatre.’

Perhaps the real problem is that the age of authenticity killed our ability to believe in glamour. Without any reason to go to Barney’s physical locations, getting out of the house just became an extra step to acquire something you can get online. Or, worse still, consumers see these purchases as money they could have spent on more “authentic” items. It’s an open question whether traditional retailers such as Barneys – once large and glamourous – can escape their fate.