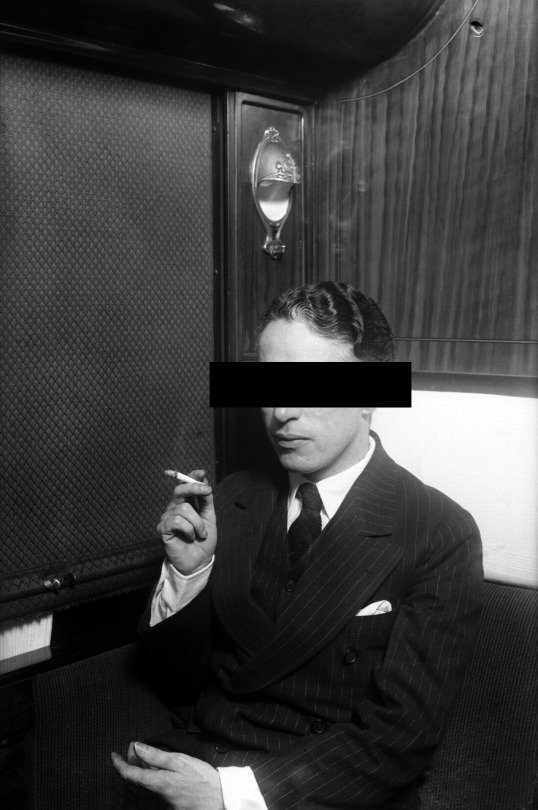

Log onto Instagram, StyleForum, and Reddit’s Male Fashion Advice on any given day and you’ll find hundreds, if not thousands, of fit pics. Fit pics, short for outfit pictures, is the online term for posting a photo of yourself to show your outfit of the day. On Instagram, there are thousands of such accounts, along with What Are You Wearing Today (WAYWT) threads on dozens of specialized online forums. Fit pics are posted in every type of men’s style community imaginable — classic, streetwear, and the avant-garde — but nearly all of them share one thing: they are headless.

Whether cropped, blurred, or blacked out, most of these photos are altered to hide the person’s face. Why? Women are fine with showing their faces through fit pics — which are called mirror pics in womenswear — although they’ll occasionally make a silly expression to take the edge off an inherently ridiculous act. It’s rare, however, for men to reveal their identities. When pressed, most will tell you they simply value their anonymity. While that’s undoubtedly true for some, I think the real reason goes deeper.

Three men shaped modern men’s fashion. The first was Beau Brummell, who gave us the suit. The second is Edward VIII, who gave us style. The third is Oscar Wilde, who gave us our stereotypes. Together, they form much of modern menswear culture, even for those who never wear a coat and tie.

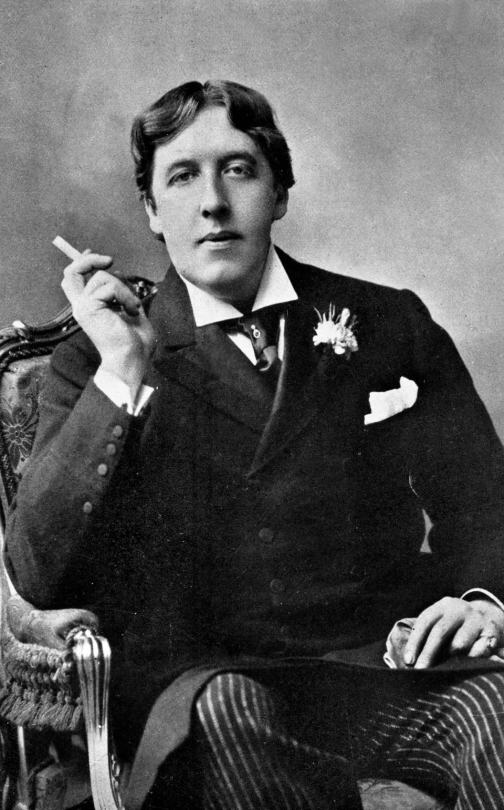

During the 19th century, Oscar Wilde recast the British discourse on dandyism and modernity with his literary and corporal posturing. The Irish playwright, aesthete, and social critic was much more than your average clotheshorse. His unceasing concern with the affective power of appearance ensured that his own distinctive and constantly changing style extended the Brummellian idea of the “pose.”

Since his admission to Magdalen College, Oxford in 1874, Wilde had always been a loud dresser. In photos of his early college days, he’s shown hanging around music halls and horse-racing tracks while wearing loudly checked suits and bowler hats. Later in life, he challenged mainstream tastes by wearing long hair, quasi-Renaissance velvet suits, and loosely tied cravats. His style drew the attention of caricaturists and earned him notoriety as the “Professor of Aesthetics” in satirical publications such as Punch. But like a Kim Kardashian of his day, Wilde knew how to convert controversy into profit. When he embarked on a promotional tour for the operetta Patience, he cranked up his sartorial exhibitionism. He wore breeches, stockings, pumps, fur-trimmed overcoats, cloaks, and wide-brimmed hats, all of which garnered him invaluable publicity.

In 1895, however, during the bleak Victorian era of England, a scandal broke out. Accused of having sexual relations with Lord Alfred Douglas, Wilde was put on trial for gross indecency. Homosexual acts were a criminal offense in 1895 — and they remained so until the 1960s — and Wilde was, in fact, a gay man. The Queensberry’s counsel produced overwhelming evidence to incriminate Wilde. Hotel chambermaids and a housekeeper testified against him, saying they saw him with young men in bed. Wilde was also extensively questioned about a line from Lord Alfred Douglas’ poem “Two Loves” (1894) — “the love that dare not speak its name” — which many interpreted as a euphemism for homosexuality. In the end, Wilde was sentenced to two years of hard labor, the maximum penalty for such an offense.

The Trial of Oscar Wilde was one of the biggest spectacles of its day. Wilde was already a celebrity as a playwright, essayist, novelist, and poet. He was admired and lampooned for his love of “aesthetic” clothing, interior design, and appreciation for the arts. He was the very glass of fashion, as well as the epitome of a cosmopolitan sophisticate. Although, there was always too a hint, especially among the British upper class, that he was a gauche newcomer and tainted by his Irish upbringing. As Christopher Breward writes in his book The Suit: Form, Function and Style, Wilde was “closer to a Brummellian style of dandyism that emphasized a degree of elitism, ennui, and in the perfection of the cut of his suits, the distanced froideur of the critic.”

Wilde’s many witticisms reflect his languor and above-the-fray attitude. In his play The Importance of Being Earnest, he writes “that we should treat all the trivial things in life very seriously, and all the serious things in life with a sincere and studied triviality.” Arthur Ransome described The Importance as the most trivial of Wilde’s society plays. “The play gives us that peculiar exhilaration of spirit by which we recognize the beautiful,” he wrote. This exhilaration is the fruitful and temporary escape from the ordinary world of moral judgment. “And it is precisely because it is consistently trivial,” he continued, “that it is not ugly.”

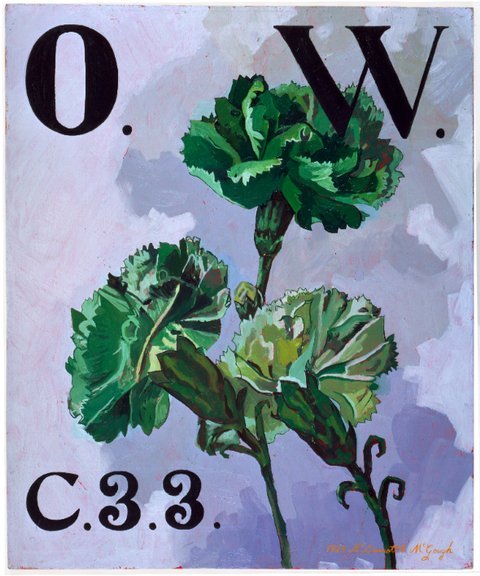

For a time, Wilde also popularized the wearing of green carnations among a specific subset of British men. He often accessorized his Savile Row suits with a green flower. When asked why, he simply answered: “Nothing whatever, but that is just what nobody will guess.” But scholars note that Wilde was almost certainly being coy. Wilde believed that nature should imitate art, not the reverse, so the green flower may have been symbolic. Could it have been that a flower of an unnatural color symbolized an “unnatural” form of love? Whatever Wilde’s intentions, the color was eventually used to hint at homosexuality. “Rent boys” plying their trade in London’s Piccadilly Circus wore green carnations to attract customers. Around the turn of the century, the mere wearing of a green suit could raise suspicions (other odd gay signals at the time included pointy suede shoes, solid-colored red ties, and light blue socks). As Max Mosher wrote in “Out of the Closet,” these coded accessories were a “quiet wink at the initiated in the same way an offhand reference to Judy Garland could determine whether a stranger was a fellow ‘friend of Dorothy.’”

The Trial of Oscar Wilde casts the longest and darkest shadow over how we see gay men today. Today’s gay male is stereotyped as being witty, effete, and an appreciator of the arts (most of all theatre). Above all, he’s an aesthete who’s interested in “effeminate” things, such as fashion (other aesthetic areas, such as architecture, are considered masculine). To be sure, from the moment the modern suit was introduced as a badge of conformity to the court, those who deviated marked themselves apart. Historians have written extensively on the supposed connection between homosexuality and a male interest in clothes — cross-dressing “mollies” (a slang term for homosexual men), the visually disruptive figure of the fop, and fashionable society gents known as the Macaroni, to name a few. But Wilde drew the most durable line between sexual identity, class, and flamboyance that continues to shape how we see gay men.

After Wilde was outed as a gay man, the 20th century saw homosexuality in all things associated with his lifestyle. Before this, flashy dress was still compatible with heterosexual masculinity. In the mid-19th century, men such as d’Orsay, Disraeli, and Balzac dressed with Wilde’s style without anyone questioning their identity. Today’s “fairy” stereotype, however, is essentially Wildean. “Pansy, nellie, swish, queen: the fairy went by many names, but one thing universally acknowledged was that he wasn’t a ‘real man,’” writes Mosher. “Sexual theories of the time suggested that homosexuals were women in men’s bodies, unnaturally devoid of masculinity. But the easily recognizable identity proved useful for lonely men desperate to find each other. Gay men flocked to the stereotype like fairies to a flame. [Later], masculine gays felt alienated from an identity that didn’t represent them; early queer activists worried that the fairy stereotype gave the community a bad name.”

This stereotype is so strong that straight men today can be very anxious about the very Wildean act of self-fashioning. “Real men,” it’s believed, are too serious and rational to concern themselves with the trivialities of fashion. And yet, throughout the 20th century, the male interest in clothing persists. Men just approach clothing in a very peculiar way. In his book Cultures of Masculinity, sociologist Tim Edwards writes:

fashionable, image-conscious or simply ‘dressy’ men are often seen to arouse anxieties in gendered as well as sexual terms, being perceived not only as potentially gay or sexually ambiguous but as somehow not fitting in, particularly in terms of rumbling any wider belief in masculinity as a form profoundly ‘un-self-conscious being-ness’ or in undermining the notion that ‘real’ men just throw things on or just are men.

As the line between gay and straight male dressing continues to blur, it’s the actual act of how we engage with clothes, rather than what we wear, that becomes gendered. Across men’s clothing forums, heterosexual men — men who are clearly interested in style — take great pains to make sure they don’t draw attention to their concern for appearance. The term outfit pics is shortened to fit pics because of the effeminacy of the word outfit. Shopping, which is effeminate both as a word and an act, is couched in masculine, man-of-action metaphors such as “pull the trigger,” “take the plunge,” and “investing.” Some men also rationalize their clothing choices — a hat is necessary for the weather, a suit is worn for respect, and putting on a tie is simply something grown men do. This allows them to claim their choices are about masculine values, such as utility and rationality, rather than purely for aesthetics. Of course, no claim better embodies this than, “I’m into style, not fashion.” Fashion is for women, but style is for everyone.

In his International Journal of Fashion Studies essay “Fashion vs. Style,” Nathaniel Weiner writes: “Both fashion-as-labor and shopping-as-achievement involve boundary work to masculinize behaviors otherwise coded as feminine. This allows heterosexual men to enjoy clothes and shopping without experiencing any gender anxieties. In fashion scholar Ben Barry’s research on Canadian men’s attitudes towards fashion, he found that because interest in men’s fashion is associated with gay men, his heterosexual male research participants saw online menswear communities as a safe place to discuss fashion without their sexuality coming into question.”

Forums today are spaces for men to enjoy clothes and consumption without their masculinity being tainted by fashion’s perceived femininity. They’re not only useful for finding information, but also the activities that generally come with shopping for clothes. In the physical world, women often shop together and rely on each other’s opinions in order to make better choices. They’ll ask for a friend’s advice on an outfit or whether an item is worth buying. In this sense, shopping isn’t just necessary for acquiring things; it’s also a social activity.

For many heterosexual men, shopping for clothes as a group raises too many anxieties. But feedback is useful, so the activity goes online. At StyleForum, men post photos of themselves for feedback to get opinions on how they look. There’s also a thread titled “Should I Buy,” which is essentially the online version pulling something off the rack and getting your friend’s opinion. By doing this anonymously, however, with heads cropped and faces blurred, heterosexual men can feel more at ease about their behavior. At some point, no gendered language can cover up the fact that you’re asking people to check out your outfit, so hiding your face will have to do.

It’s easy to get down on this as an example of homophobia, but as Weiner notes in his essay, online menswear communities have made fashion more democratic and participatory. With rare exceptions, most heterosexual participants are very inclusive — they’re just anxious about their own identities. And by making fashion forums feel more welcoming, a whole new wave of people can start enjoying what they wear. It’s important to remember that, before fashion went online, this industry wasn’t known for its inclusivity. Fashion was for the young, handsome, and most of all, very rich. Today, almost anyone can go online to get style advice — men of nearly every body shape, age, and economic class. If you give gender anxious men a little cover, they’re more than happy to support their peers. As ever, today is the best time in fashion, and tomorrow will be better still.