While fashion writers focus on the runway, actual fashion moments often happen on film. Marlon Brando’s smoldering look in The Wild One helped to cement the black double rider as the rebel uniform, just as the opening scene of Breakfast at Tiffany’s refashioned the black, sheath evening dress into a womenswear icon. In his 1985 book Elegance, Bruce Boyer calls these cinematic touchstones the “moments that signal or symbolize a shift in the old modus oprandi.” These scenes, as unimportant as they may seem, later become the film equivalents of the most memorable lyric in a song. And in being so, they change the ways we see clothing.

Boyer traces the moment when tassel loafers became an acceptable form of business dress to a particular scene in the 1962 film That Touch of Mink. The scene starts with Cary Grant, who plays the familiar international corporate head, walking into his wood-paneled office on Madison Avenue one average morning. “He’s wearing his familiar dark, impeccably cut business suit, white shirt, conservative tie, and black straight tip oxfords. He is the very glass of business fashion, the mold of form,” Boyer writes. Yet, upon settling in, Grant “removes his suit jacket and town shoes, and dons a discrete, but obviously very comfortable, lightweight cardigan and a pair of tassel loafers! Right there in the office!” In today’s business culture, where everyone wears jeans and sneakers, this story has a quaint ring to it. But as Boyer notes, this is just one of the many “less-than-earthshaking events that mark the road we have traveled.”

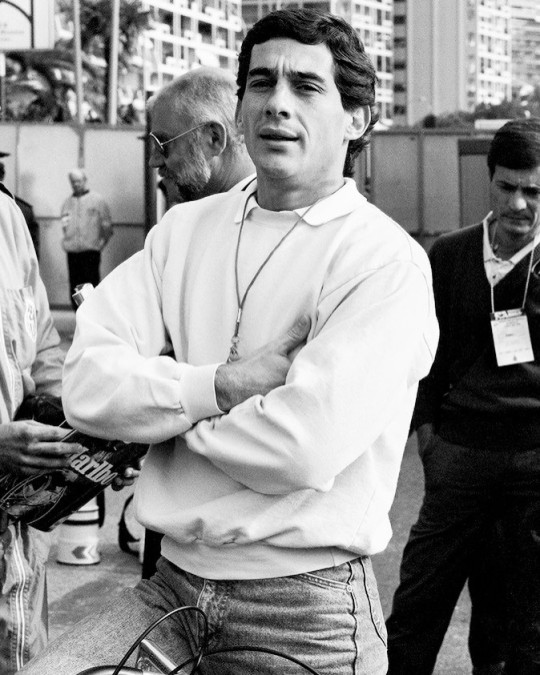

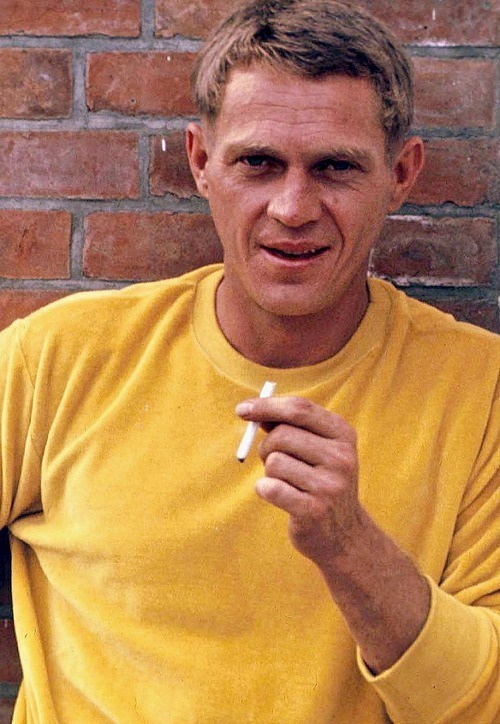

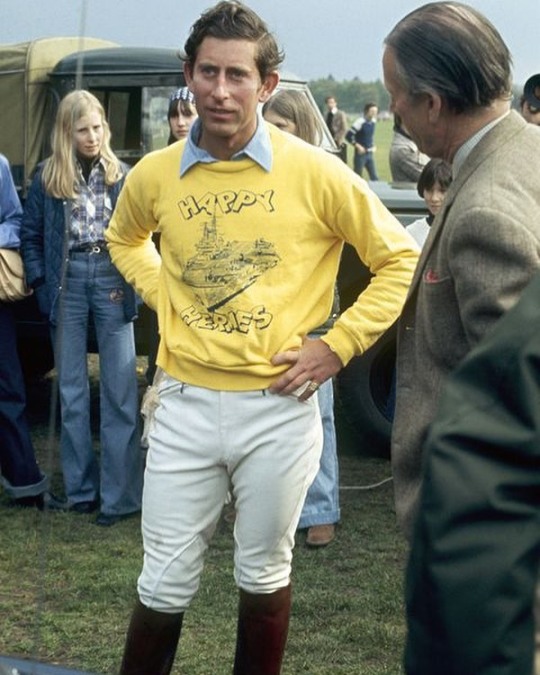

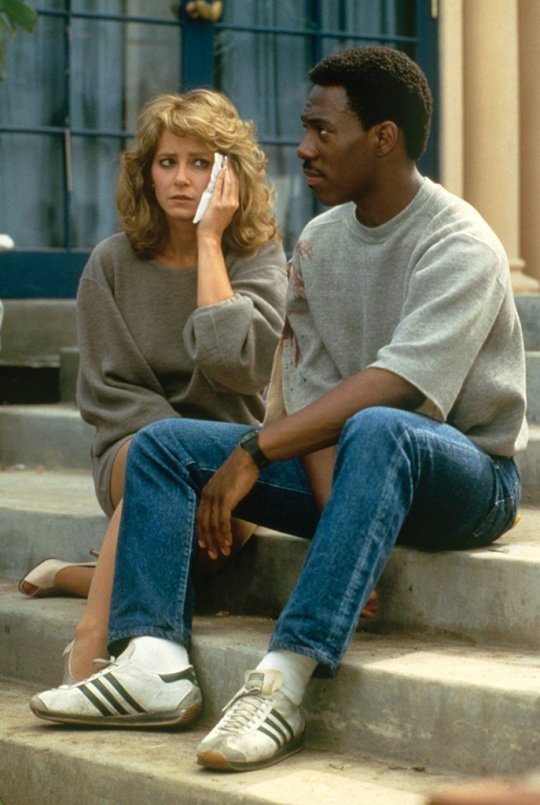

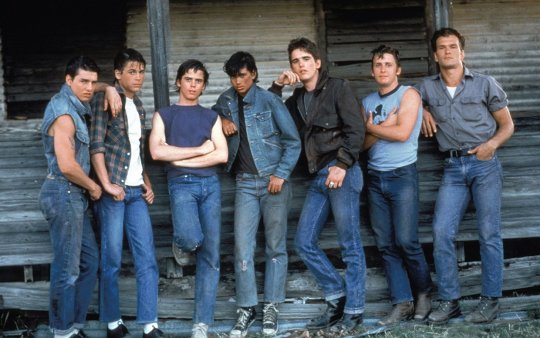

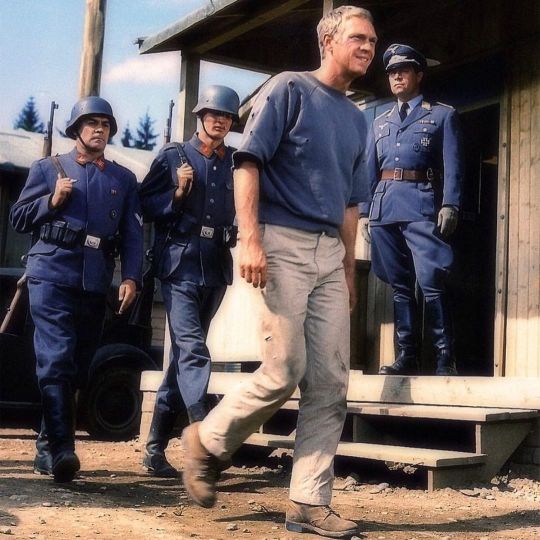

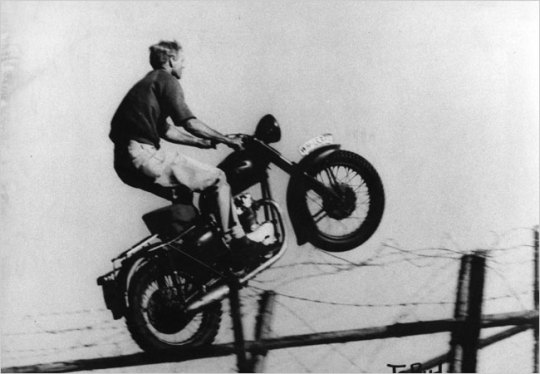

A similar moment happened for the sweatshirt, that mass-manufactured item that has none of the rock ‘n roll cool of biker jackets or the blue-collar credibility of blue jeans. Yet, when Steve McQueen wore a dusty blue sweatshirt in the film The Great Escape, particularly in that scene when “The Cooler King” raced through the mountain trails and slid into a barbed-wire barrier, the garment attained a touch of cool. The sweatshirt is as iconic as every other notable American garment – blue jeans, black double riders, sack suits, penny loafers, and button-down collars – and it symbolizes the same independent American spirit. Much of that is thanks to McQueen (or, really, his stunt double, Bud Ekins, who did the hard work in that chase scene).

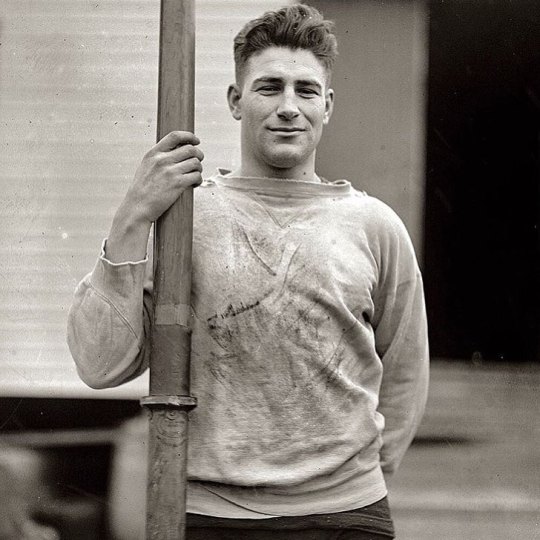

Before that cinematic moment, the unassuming sweatshirt was just a solution to a problem. During the early 20th century, sportspeople wore heavy woolen knits, often in grey, before and after training. These sweaters were itchy against bare skin, difficult to wash, slow to dry, and expensive to procure. This all changed in the 1920s, when the American brand Russell – founded by Benjamin Russell in Alexander City, Alabama in 1902 – refashioned something from their line of women’s underwear called a union suit. The design was done at the behest the company founder’s son, Bernie, who was an avid football player at the University of Alabama. Bernie wanted something cheaper and more practical to wear while training, so he had his dad modify the company’s women’s union-suit top for him and his teammates.

Imagine how revolutionary this would sound today: a college boy asking his father to redesign a piece of women’s underwear for his male teammates to wear in the gym (to be fair, the underwear style at the time had also bled into men’s wardrobes, although Russell pulled the original template from their women’s line). The history of the sweatshirt is just one of the many examples of how gender norms have, in some ways, actually become stricter over time, ignoring the historical fluidity between the two aisles. Around the time of the sweatshirt’s introduction as an athletic garment, Time Magazine printed a chart showing sex-appropriate colors for girls and boys (girls were told to wear blue, boys were to wear pink – assignments that have switched). Before this, little boys and girls wore frilly white dresses. Today, children’s clothing is highly gendered, sometimes disturbingly sexualized, partly because people worry about their kids growing up with the “wrong” gender identity (something dress historian Jo Paoletti covers in her book Pink and Blue). Years ago, men were so worried about looking feminine, questions such as “can I wear a pink shirt” commonly cropped up on StyleForum.

Nonetheless, shortly after the sweatshirt was introduced, this remade women’s garment was distributed to four American college football teams, where it became an instant hit. Since then, the sweatshirt has been worn by professional and amateur athletes alike, across different sports, and on and off the field. Now, the plain and familiar sweatshirt is considered as much of an icon of masculinity as blue jeans and leather jackets.

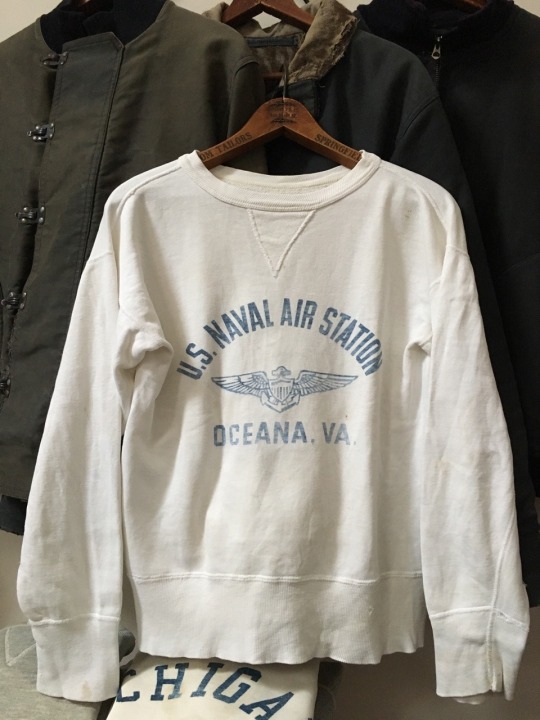

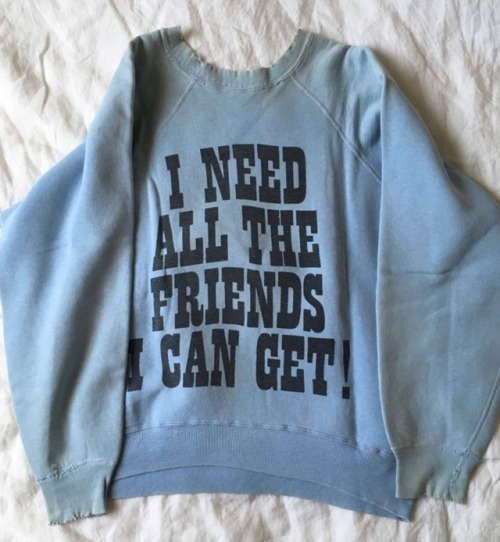

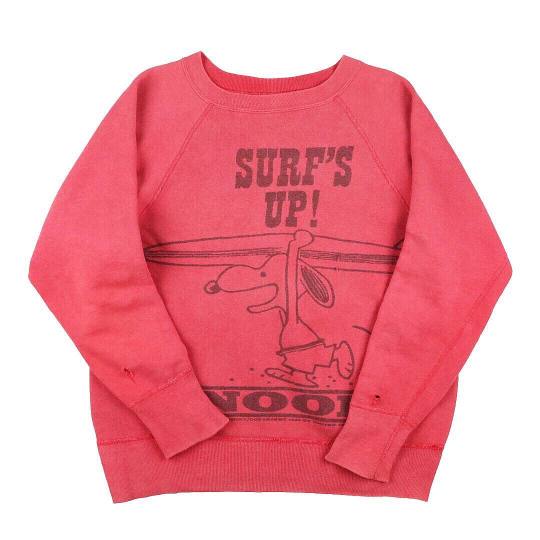

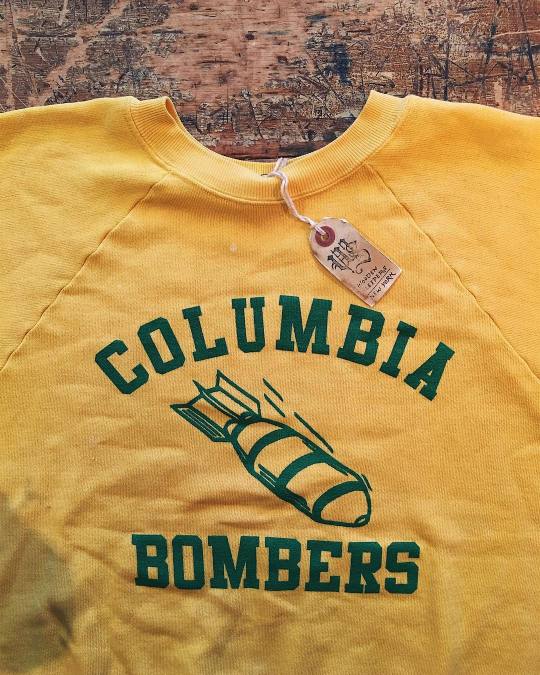

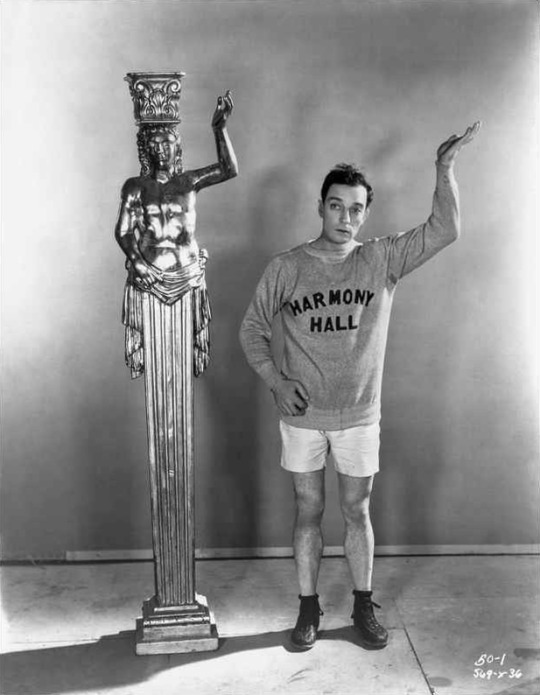

The sweatshirt didn’t reach its potential until the 1930s, however, when Abe and Bill Feinbloom — the two brothers who founded Knickerbocker Knitting Company, which today trades under the name Champion — found a way to print raised lettering on sturdy cotton knits. Soon, the sweatshirt wasn’t just a symbol of sport, but also personal identity. Printed messages allowed people to show their allegiance to specific clubs, teams, and companies. Culturally, the sweatshirt is everything: a useful garment you can wear, an inexpensive thing to produce, a cheap item to purchase, a marketing tool, a souvenir, and a symbol of identity. Add to that the allure of Steve McQueen, and you can see why the sweatshirt has attained such status.

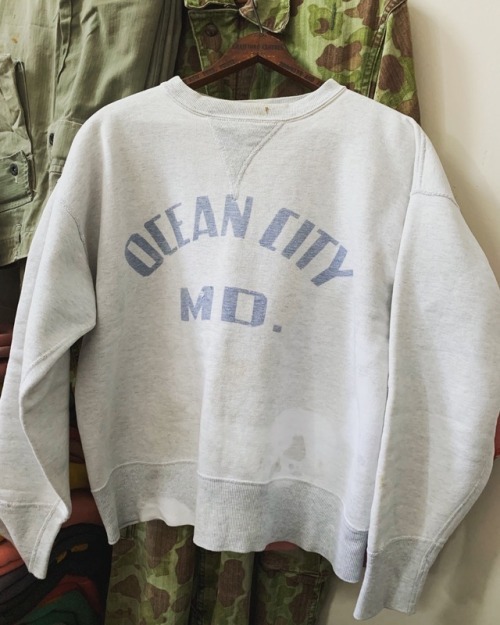

It’s been over a decade since menswear was obsessed with all things Americana and workwear. And yet, sweatshirts continue to be one of the most useful items in my wardrobe. They’re to Americana and workwear what Shetland sweaters are to Ivy and trad. You can wear them with leather jackets, chore coats, denim truckers, offbeat Japanese workwear, and even a bit of contemporary casual. They serve as a useful background to an outfit, can be machine-washed, and look better with age. When I don’t have time to iron a shirt, I’ll often throw on a sweatshirt because it’s comfortable and easy to wear. I find heathered grey is the most useful color, distantly followed by stone, dusty charcoal, muted blue, and olive.

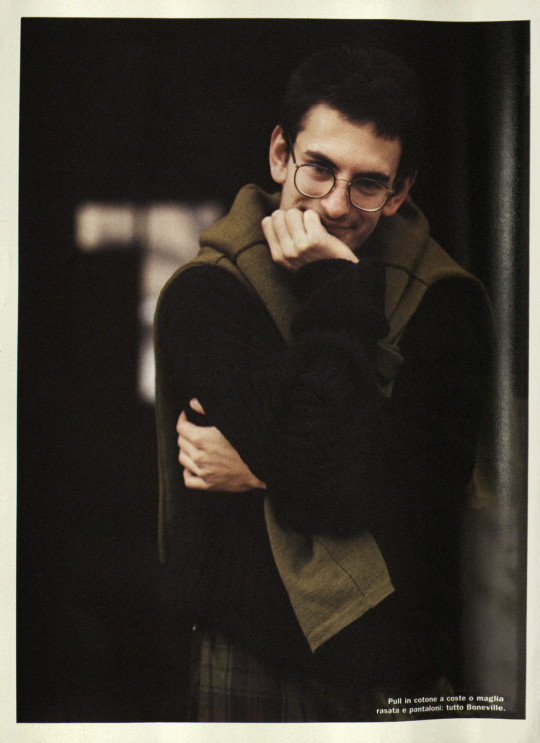

If you have the scratch and love vintage Americana, it would be hard to beat one of the high-end Japanese-made sweatshirts from companies such as Buzz Rickson, The Real McCoys, and Studio D’Artisan. They’re made on old world loopwheel machines, which are slow and inefficient by modern manufacturing standards, but put less tension on the threads while knitting. It’s said this produces a better garment. Loopwheel knits are a little closer to the mid-century originals and are highly sought after by clothing collectors. I find these Japanese-made knits are stout without being suffocatingly thick. Their looser, slightly rounded bodies look more casual than streamlined sweatshirts. And they age impressively well. My Buzz Rickson sweatshirt has kept its shape, despite repeated washings over the last seven years.

I’ve also been impressed with the looser, more fashion-forward sweatshirts from Chimala and John Elliott. They’re wider and slightly cropped, which gives them a unique silhouette (Alexander Wang does something similar, but I find the material is less dense). Both companies offer them in a variety of interesting finishes. I bought this one from John Elliott this season, and despite being skeptical — perhaps even snobbishly adverse — to the brand’s hype, this sweatshirt is pretty good. The sun-faded blue color is perfect with blue jeans, but can also be worn with olive fatigues, black denim, and tan workwear chinos.

Champion is known for their reverse-weave sweatshirts, which means the light ribbing runs horizontally across the body, rather than vertically up it. It’s said this helps minimize shrinking, no matter how many times the garment is washed, although I haven’t had any issues with shrinkage with other sweatshirts (shrinkage!). Modern Champion sweatshirts aren’t quite up to the standards of their extra beefy 1980s classics, but their collaboration with Todd Synder is genuinely good. My friend Pete also vouches for Pennsylvania’s Camber label. “Camber has been the label-under-the-label for a lot of streetwear brands, including Bape offshoot Very Ape, Futura stuff, and, rumor has it, Engineered Garments Workaday,” Pete writes. Prices are impressive at just $65, but you have to love the slightly roomier fit. The French boutique Beige has fit pics.

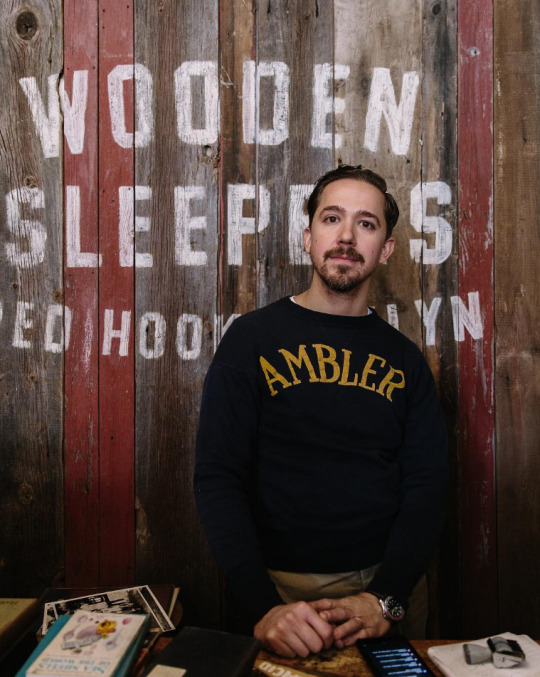

Other great companies include Levi’s Vintage Clothing, 3sixteen, Sunspel, Reigning Champ, Battenwear, RRL, Velva Sheen, Lady White Company, Columbiaknit, TSPTR, and Merz b Schwanen. Markkt, the online marketplace for secondhand workwear, is worth a look if you want one of those Japanese knits for a little cheaper. And there are vintage shops such as Wooden Sleepers, where you can get something with cool provenance and a rare, faded-out print. As usual, it’s worth digging around Etsy.

Lastly, don’t discount cheaper, everyday brands such as J. Crew. I find mall-bought sweatshirts are a little more likely to lose their shape – particular around the ribbed hem, which means the sweatshirt will “hang” on you, rather than create a tautly knit, rounded shape – but you can always throw them into the wash and then dryer. That should snap the garment back into its original form. The color may dull from being in the dryer so often, but … it’s a sweatshirt. Faded is better.