Before nostalgia was considered sweet sentimentality, it was thought of as a mental disorder similar to paranoia. In the late-17th century, a medical student named Johannes Hofer coined the term to describe a set of peculiar anxieties he observed in Swiss mercenaries fighting abroad. Symptoms included melancholy, loss of appetite, and an intense longing for bygone times. Initially, nostalgia – from the Greek nostos, meaning homecoming, and algos, meaning pain – was mostly associated with soldiers. The Swiss military even forbade the playing of a particular milking song, Khue-Reyen, for fear that it would lead to desertion or suicide. But soon doctors found other people afflicted with the mania: newly arrived immigrants, children sent off to the countryside for nursing, and women who were forced into domestic servitude.

Until the turn of the 20th century, the Western medical community came up with all sorts of strange remedial measures for nostalgia. Among the many dubious cures were using leeches, purging stomachs, and even shaming the condition out of patients. During the American Civil War, a military doctor named Theodore Calhoun thought nostalgia was a symptom of the weak-willed and unmanly. In a paper titled “Nostalgia as a Disease of Field Service,” which was read before a medical society, he maintained that “battle is to be considered the great curative agent of nostalgia in the field,” for men would find themselves with a clearer mind after having survived an onslaught. In her book Homesickness: An American History, Susan J. Matt recalls this passage from Calhoun’s stunning lecture, where he recommends public ridicule as a cure:

Any influence that will tend to render the patient more manly will exercise a curative power. In boarding schools, as perhaps many of us remember, ridicule is wholly relied upon and will often be found effective in camp. Unless the disease affects a number of the same organization, as in the case narrated above [Dr. Calhoun is referring to a case in which there is something of an epidemic of nostalgia in a particular regiment – where “nearly all who died were farmers” – before he came to its rescue], the patient can often be laughed out of it by his comrades, or reasoned out of it by appeals to his manhood.

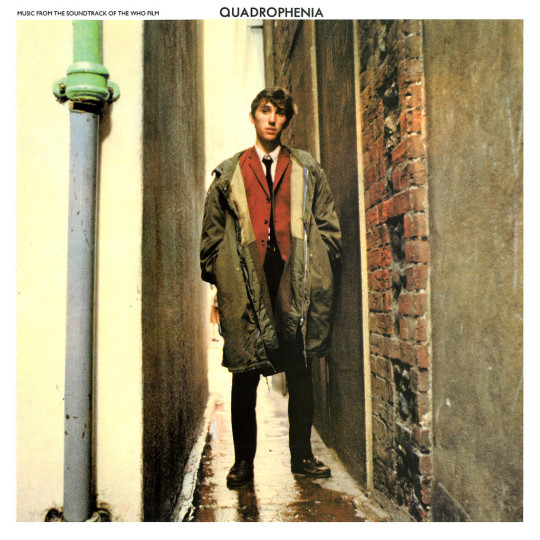

Menswear is naturally heavy with nostalgia, partly because borrows so heavily from the past. But among the things in my wardrobe, few things induce the emotion as strongly as raincoats (thankfully, doctors haven’t recommended bullying yet for me). Every time I put on a raincoat during one of those dark and gray mornings, I remember the little marches I used to make to elementary school while bundled up in a googly-eyed Cookie Monster sweater, vinyl raincoat, and sturdy rubber boots. That coat, cold and clammy as it was, made me feel wonderfully impervious as I splashed into puddles and trotted through the rain until I arrived at a harshly lit classroom. Seven hours later, I would be back in that protective plastic coat again when I went to rejoin my mother.

Perhaps that’s why young men eschew such sensible items once they hit their teens. Eager to seem independent, they try dodging the rain with a quick pace, but ultimately end up with sopping clothes and squishy toes. Jacob Gallagher, the Men’s Fashion Editor at The Wall Street Journal, explored this mystery when he wrote about Male Nojacketus, a confounding species of men who, for some reason, refuse to wear coats in the winter. “What drives these men to dress so inadequately for the weather? Is it a macho thing?,” he asked. “Did they forget to check the forecast on their way in from warmer climes? Are they simply trying to prove their mothers wrong after years of being told ‘Jimmy! Put on a coat, you’ll catch a cold?’” We’ll never know for sure.

Like many men, I rediscovered a love for raincoats when I got older. It doesn’t hurt, of course, that they’re immensely practical this time of year. A good raincoat can serve as a kind of armor against rain and wind, yet it’s light on the back and easy to carry across the arm. Some of the rubberlike materials can be mashed to death, but will always spring back to shape, which makes them good travel companions. Mostly, I like raincoats for their sweet associations. For me, they represent maternal diligence, a more innocent time, and familiar routines. Besides, good raincoats are often knee-length, which means they swish around when you walk, adding a sense of drama and style – and who couldn’t use more style?

THE REDOUBTABLE TRENCH COAT

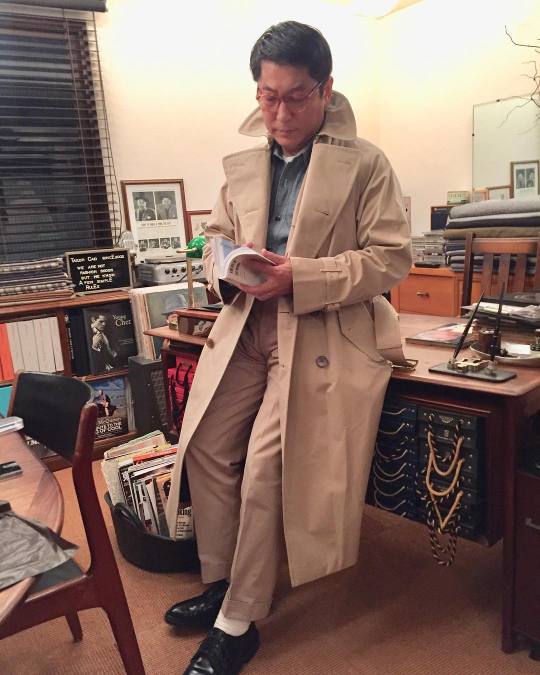

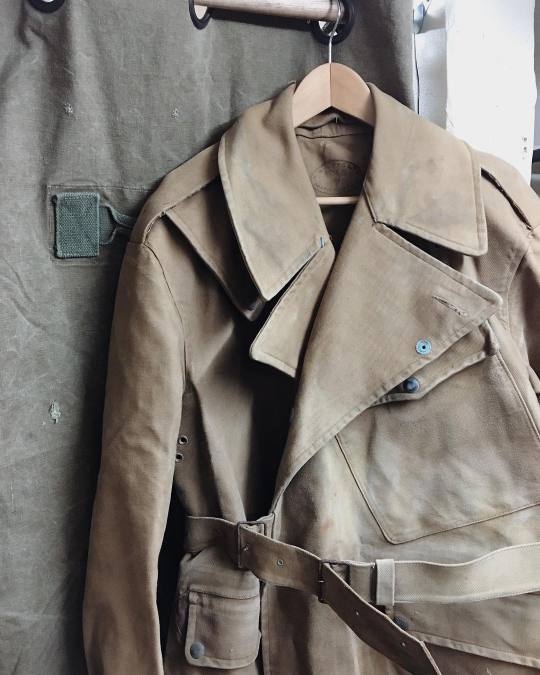

The most classic of weather gear is the redoubtable trench coat. Rendered in vanilla cream or muddy taupe, it’s a design that comes out of British military history. When it was first introduced, it was available to British officers who wanted an alternative to the heavier serge greatcoat. Its design was literally built for the miseries of trench warfare: epaulets to help anchor shoulder bag straps, storm flaps to keep out water, and buttoned tabs to hold the collar high on the neck during a downpour. The D-rings were used to carry map cases, swords, or belt utility equipment. After the Second World War, this military garment was pressed into civilian service as men found the waterproofed khaki cotton useful for the rain. When worn downtown, travel umbrellas and cameras were slung off the coat’s repurposed D-rings. And the trench’s original role as part of an officer’s uniform gave its new wearers a kind of businesslike respectability.

It’s impossible to talk about the trench coat without mentioning its cultural associations. Defenders of the style will point to Humphrey Bogart on a wet tarmac in the final scenes of Casablanca; John Cusack standing on a lawn, holding a boombox high above his head to win a woman’s heart in Say Anything; and Prince wearing a bespoke purple trench coat, singing his hit single “Purple Rain” in the climax of a movie by the same name. But for many men of my generation, this double-breasted coat is less noble. It’s the garment of nude flashers, Inspector Gadget, and more sadly, the two mass murderers who shot up Columbine, a tragedy that won’t stop re-haunting us to this day.

There’s nothing I can say that will shake those deep-seated associations. I can only say that I think it’s possible to wear a trench coat well and blending in is overrated. The style is better in its original silhouette, long and oversized, designed to be thrown over a suit or sport coat. Burberry continues to make the best ones, which you find for pennies on the dollar at any thrift shop, but Coherence, Grenfell, Aquascutum, and Brooks Brothers are also worth a look. Just avoid anything too skimpy. Although they sell well, modernized thigh-length versions lack the utility and glory of the originals. Wear them with classic tailored clothing, and take comfort in knowing that leading designers such as Christophe Lemaire and Raf Simons are bringing back fuller silhouettes anyway.

THE STREAMLINED MAC

If you remain unconvinced, try the more streamlined mac, which is what I have in my closet. The design is close to what most will imagine as a classic topcoat with its single-breasted closure, fold-down collar, and two outer slash pockets. The reason why these are called macs and not topcoats has to do with a little-known 19th-century Scottish chemist named Charles Macintosh, who came up with a way to waterproof fabric. His solution involved spreading a thin layer of rubber, softened by naphtha, between two pieces of cloth, heating them up, and then pressing them together. Originally dubbed “India rubber cloth,” Macintosh’s process was for making any material waterproof – silk, hemp, linen, wool, and leather included – but it’s since become best known in its stout and reliable cotton form. When these bonded fabrics are transformed into raincoats, the seams are taped and the linings are affixed with glue. The result is a sturdy three-layer system of cloth and rubber, completely sealed in even at the seams, which guarantees near impermeability. The style is so synonymous with rainwear that even today, any single-breasted raincoat of this design is generically called a “mac” in Britain.

I love bonded cotton macs because they allow for one more exciting material to be in a wardrobe. They breathe about as well as a trash bag, but they hang beautifully and allow for interesting silhouettes. In an old blog post at the now-defunct A Suitable Wardrobe, Andrew Yamato wrote of it: “In the sartorial strike zone between 40 and 70 degrees, Mackintosh cloth is uniquely sensuous stuff. It doesn’t drape so much as it sculpts the shoulders, tucking into crisp folds under the cinched belt before flaring out into a wide skirt that’ll keep your trousers dry even without an umbrella. As you move, it rustles like a gently luffing sail. It smells profoundly good – an atavistic aroma of rubber, canvas, and glue that conjures reliable old camping gear.” Like any good piece of outdoor equipment, a bonded cotton mac makes you want to be outdoors.

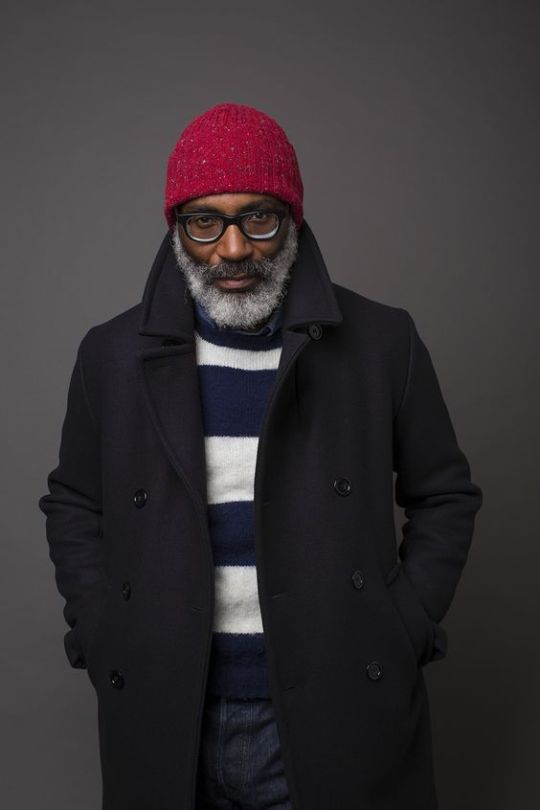

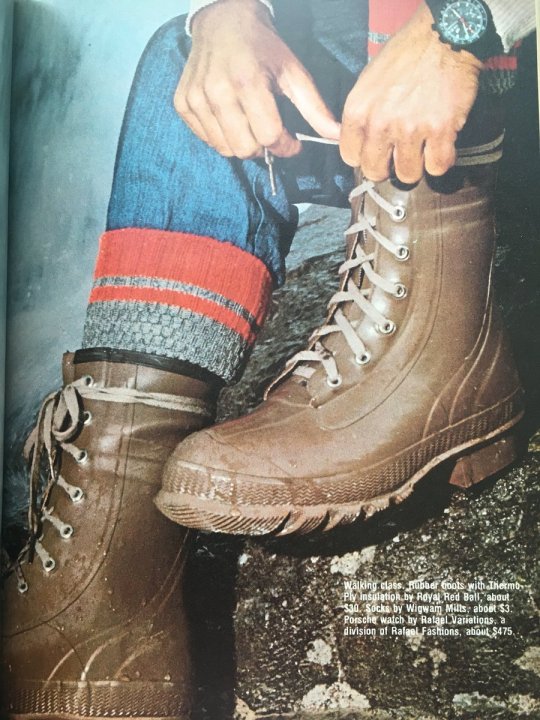

The canonical mac today is still made by Mackintosh, named after its Scottish founder. The style goes naturally with suits and sport coats, but I find it also makes for an easier pairing with modern casualwear than cotton gabardine trenches of any color. Much like the trench, however, you’ll want to avoid ones that are too short (I wouldn’t go higher than mid-thigh length). Cropped macs do a poor job of keeping your legs dry, and they look a little dated. If you buy one from Mackintosh, make sure you’re getting the rubberized cotton version, which is their specialty. Good alternatives can be found at Coherence, Grenfell, O’Connell’s, Private White VC, Todd Snyder, Camoshita, and AMI. Wear them with sport coats, tailored trousers, and country brogues. Or team them with a pair of raw denim jeans, a chunky sweater, and some LL Bean duck boots.

MORE CASUAL ALTERNATIVES

If the options above feel too dressy for you, the good news is that almost any kind of outerwear can be made water-resistant with a durable water repellant spray. The technology works much like the waterproofers you may have used to protect a fresh pair of suede shoes. The treatment creates a million microscopic follicles that stand up on their ends, making it harder for the surface tension on water to break. As a result, you get a quicksilver effect with water droplets rolling off your back, rather than soaking into your garment’s fibers. Among the more popular DWR treatments are Nikwax, Revivex, and Grangers. Note, these follicles tend to break and bend when they’re mixed with dirt, which means you have to reapply the treatments every once in a while. ProLite Gear has some good videos covering these solutions on their YouTube channel.

Alternatively, if you’ve been interested in men’s style for any length of time, you probably already have some outerwear that can double as a raincoat. Waxed cotton Barbours, M-51 fishtail parkas, and various kinds of sportswear come from a long tradition of workingmen’s protective gear, which means they’re naturally built to withstand a good deal of wind and water. Granted, many of these styles come in a slightly cropped length that will be less useful for torrential downpours, but as Bruce Boyer notes, many of us don’t spend as much time in the elements the way people used to. “These days people go from their homes to their attached garages, drive to work and park in the underground lot, take an elevator to their office, and then repeat the trip in reverse at the day’s end,” he wrote in True Style: The History and Principles of Classic Menswear. Workwear coats are as much about their rugged sensibility and better-with-age quality, as they are about protection. Here are some general categories I particularly like:

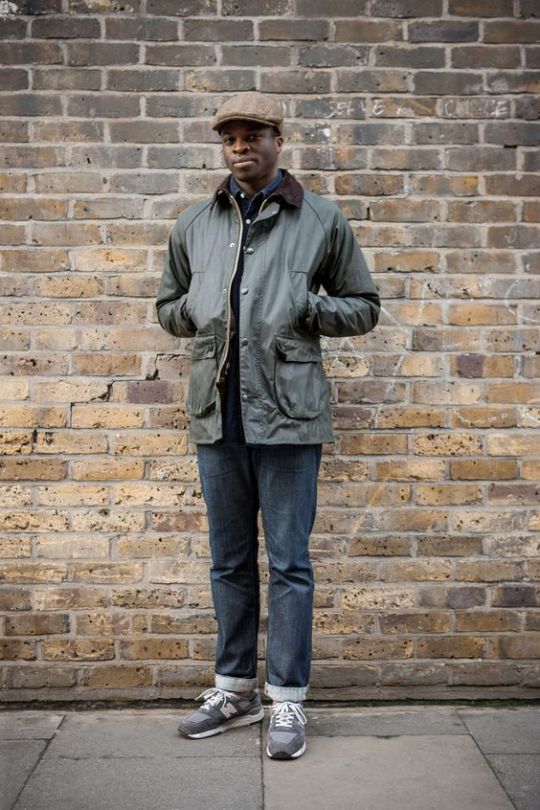

Classic Waxed Cotton Jackets

Supposedly, the first people to wear waxed cloth on their back were sailors who oiled sailcloths before cutting and sewing them into rain capes. The waxed cottons we see in Barbour-style jackets today are much softer and more refined than those, mercifully. Here, Egyptian cotton is typically impregnated with a paraffin-based wax, which makes the material reasonably breathable and supple. Barbour’s history as the preferred brand of British farmers and gamekeepers makes it a good match for the estate tweeds and spongey Shetland sweaters many of us favor this time of year.

If you only plan to wear with the jacket with sweaters and jeans, try Barbour’s Bedale. It’s a short equestrian jacket with internal sweater cuffs and dual side vents. The slightly shorter length won’t cover the hem of a sport coat, but it’ll may feel more natural given your other outerwear. The Beaufort, on the other hand, is a shooting jacket with a big game pocket at the back and slightly longer length by an average of 2.5″ (depending on the size). I prefer that longer style for layering over sport coats, but the adjustable Velcro cuffs aren’t as comfy as the Bedale’s sweaters cuffs, and the ventless back means the jacket can ride up when you put your hands in your trouser pockets. You can usually get the best price on both models at End.

Just as the trench coat is a classic British military garment, Barbour comes from British sport and countryside pursuits. For decades now, it’s been the simple grab-and-go garment you can throw over a tweed jacket when running errands, heading to the pub, or even fishing for trout. Starting in the 1980s, however, Barbours became popular with Sloane Rangers, sometimes affectionately referred to as Sloanies. These youths embraced Barbour as part of an upper-middle-class uniform, in part to mimic the numerous photos of the newly-wed Charles and Diana wearing theirs while at their country home. I like the look, but some will reasonably think of the Tories Of Bumble Instagram parody account.

If you want to shed the class associations, but keep the rugged style, try Belstaff’s Roadmaster, which is a racing coat adapted from something motocross competitors used to wear at the Scottish Six Days Trial, a grueling event where bikers covered as many as 100 miles a day. Built with a waxed cotton shell and a belt for secure closure, this jacket makes for a great casual raincoat. I wear mine with a Buzz Rickson sweatshirt, 3sixteen slim-straight jeans, and Viberg service boots. Ratty, plaid flannel shirts also make for natural pairings, even if you’re only wearing this to ride out a storm.

Emerging Tech-Classic Sportswear

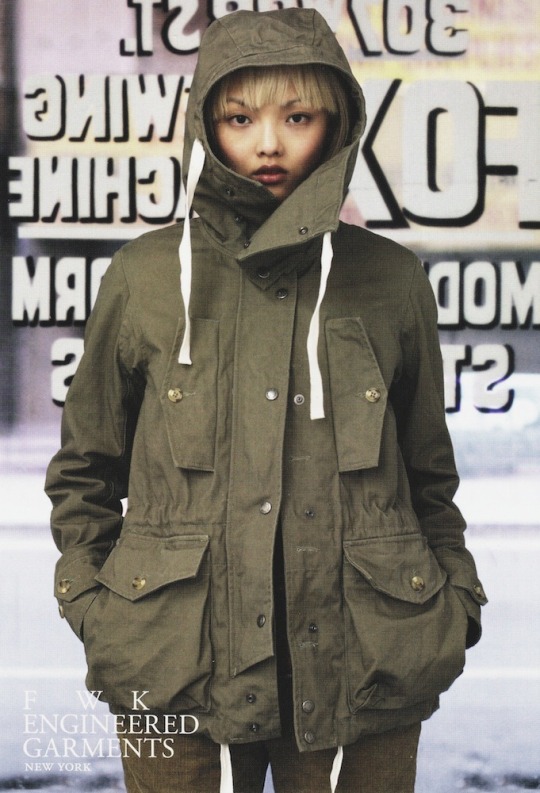

A lot of men’s fashion today can be broken into two camps. On the one end, you have heritage (and heritage-inspired) brands that rely on the classics. On the other end, avant-garde labels are creating conceptually interesting – even if hard to wear – designs that break from the past. Ten C and Norwegian Rain sit between these two worlds, perfectly blending techwear with heritage, innovative fabrics with canonical military design. Think of them as Stone Island meets Nigel Cabourn.

The innovation here starts at the material level. Instead of traditional weatherproofing techniques, such as impregnating cotton with liquified rubbers or paraffin waxes, these companies embrace advanced poly-blends. Ten C uses a jersey that behaves a bit like Ventile, which was favored among Allied troops for its stealth quality. When dry, these fabrics feel like any other soft, plain weave cotton (although Ten C’s jersey is a touch stiffer to lend shape), but when wet, the fibers swell and pores close up, making the material impermeable. Norwegian Rain, similarly, backs their recycled polyester with a waterproof membrane. The result is a more breathable, lightweight garment that wears comfortably in warmer climes.

For me, the real innovation is in the pattern making. Ten C and Norwegian Rain hint at vintage militaria, but details are more sophisticated with enveloping hoods, stand up collars, and unusual revers. Cleverly designed straps and button systems allow these coats to take on strange, almost futuristic forms. They’re a perfect choice for men who want something a little more updated than a Barbour, but still enjoy the security that comes with classic menswear design.

British Adventurer Wear

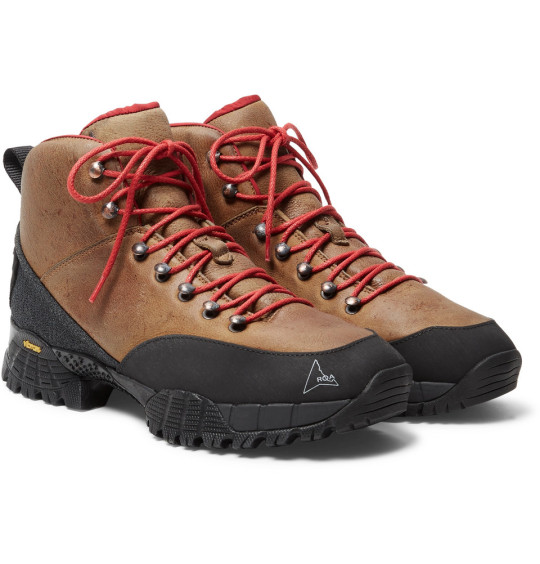

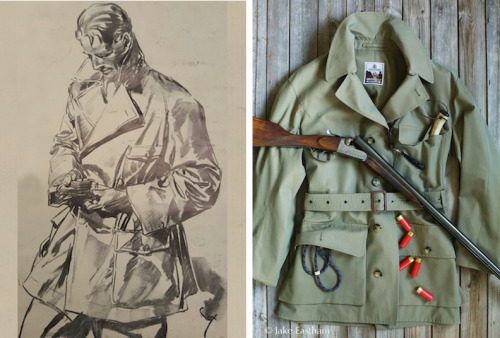

For a guy who has never explored anything but his fridge, I have a strange fascination with British adventure wear. You know the stuff – waxed hunting coats, mountaineering anoraks, belted storm parkas. One of the greatest names in this field is Grenfell, a label given to a specific kind of tightly woven, cotton gabardine. Throughout the 20th century, Grenfell cloth has been worn by sportsmen, adventurers, and pioneers. Malcolm Campbell used it for a racing suit when he broke records at Daytona Beach and Bonneville; medical missionary Wilfred Grenfell used it for a cagoule when he pulled sleds to see patients; and David Attenborough used it for a walker jacket when he studied Rwandan gorillas. The cloth has even been used to keep mountaineers warm. F.S. Smythe slept in a Grenfell tent in 1933 when a snow blizzard drew him to his knees on Mount Everest. Pitched at 27,000 feet, the tent set a record at the time for being the highest point of man-made habitation.

For the longest time, the new Grenfell company only offered traditional raincoats. In the last few years, however, they’ve gotten a little more adventurous with their designs, drawing on old Grenfell catalogs, as well as archival pieces the company once made for Eddie Bauer and Abercrombie & Fitch.“Grenfell originally designed the Shooter in 1947,” Gary Burnand, the company’s strategy director, once told me. “It’s a modified version of the trench coat – retaining the belt and reinforced shoulders, but made shorter for shooting and driving.” Some of my favorites from them include the Shooter and Despatch coat, but I’m in most awe of the raincoat modeled on Yasuto Kamoshita at the top of this post, which is coming this fall. That one would be great, I imagine, for the adventurous trek I take to my office, just like I once wore that vinyl raincoat over a Cookie Monster sweater while walking to school.