If you were just getting into menswear ten years ago, you likely updated your wardrobe in one of two directions. The first was the sort of skinny lapeled, Mod-inspired tailoring that prevailed after Mad Men debuted in 2007; the second was a sleek and colorful “metrosexual” style that was represented through Queer Eye for the Straight Guy. Those two looks dominated the editorial pages of GQ and Esquire, who showed the before-and-after transformations of men who learned how to buy slimmer clothing – and get things made slimmer still through a local alterations tailor.

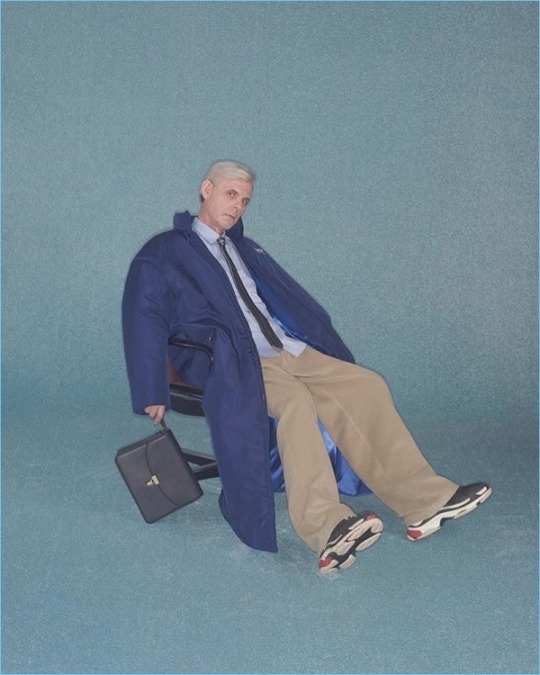

Today, those transformations are running in the opposite direction. Silhouettes are filling out and dressing like a dad is coming back in. High-fashion boutiques now stock the kind of “sensible” clothes your father likely buys from Kohl’s: relaxed-fit jeans; vacation shirts; schlubby tennis shoes; tactical fanny packs; and pastel-colored, washed-cotton caps (“they’re soft, shapeless, and familiar – just like dad,” writes Pete Anderson at Put This On). Mr. Porter even stocks the most fatherly of leg coverings this season: zip-off cargo pants that convert into cargo shorts, giving value-minded fathers a two-for-one (which is good since Mr. Porter’s version is a mind-boggling $1,000).

You can chalk some of this up to the fashion cycle. Once a look becomes popular, first adopters move on, thus swinging the pendulum in the other direction (fuller silhouettes give way to skinny silhouettes until the second collapses and fuller styles prevail again). The other is about the rising influence of Demna Gvasalia, the Georgian designer who led the design team at Maison Margiela before becoming the creative head at Balenciaga and his own label Vetements. When he showed his spring collection last year at the verdant Bois de Boulogne park in Paris, he sent models down the runway in “oversized color-striped windbreakers, pale jeans similar to those that made Barack Obama dad-in-chief, and bloated running shoes in the style of podiatrist-approved Asics.” Male models even carried children, the most literal interpretation of the trend. Dad style today is so au courant, Democratic Vice Presidential nominee Tim Kaine even tweeted about it.

How did such a staid look become popular? Fashion writers have suggested it’s connected to ‘90s nostalgia, a new appreciation for practicality, and simple fashion exhaustion. In his piece on the rise of dad style, Wall Street Journal fashion editor Jacob Gallagher wrote: “it can be a relief to opt out of the edgier style game. […] Men’s fashion sped up its trend cycle, rapidly hurling skinny jeans and Chinoiserie bomber jackets at us. If keeping up has left you exhausted, dad style can be an exit ramp to a comfort zone of fleece jackets and dependable khakis, the sort you relied on in college. […] Practical? Check. Comfortable? Definitely. I may already own it? Ideal.”

All those things, while true, miss one of the more interesting storylines here about how language intersects with fashion, helping to popularize a look through sound branding. To understand how, you have to go back to a little-known art collective named K-Hole, which was made up of five friends who had recently graduated from RISD and Brown University. They were toiling away in New York City trying to find their way into art careers when, one day, one of them found a curious corporate artifact.

The object was a trend forecasting report, like the ones Trendwatching and Future Laboratory churn out to help corporations understand how cultural currents can impact their bottom line. And like many of those reports, it was full of intellectual claptraps, superficial sociological analysis, and overwrought language. “Equally amused and intrigued, the friends decided to cook up trend reports of their own – an art project that would mix parodies of consumerism with their personal observations about culture,” Danielle Sacks wrote of the group at Fast Company. “K-Hole started as an art project designed to comment on the corporate world. Then, through a series of unexpected developments, it turned into another player in the industry it once provoked.”

In the following two years, they released three trend forecasting reports. The first report was about “fragmoretation;” the second focused on “prolasticity.” Having invented the language to describe certain trends, however, the team also needed to earnestly describe the phenomena these words were meant to capture. These reports caught the attention of people in the art community, but they went mostly unnoticed in the broader business world. That is, until K-Hole was invited to speak at a design conference in London, where they were challenged to think about how youth culture might look in the future. That’s when they came up with their most successful neologism: normcore.

Almost immediately after K-Hole released their fourth report in late 2013, the term normcore went viral. The New York Times deconstructed the idea half-tongue-in-cheek, questioning whether news media organizations were falling for an internet meme that had turned into a massive in-joke. Normcore, they said, was a fashion movement in which “scruffy young urbanites swear off the tired street-style clichés of the last decade — skinny jeans, wallet chains, flannel shirts — in favor of a less-ironic (but still pretty ironic) embrace of bland, suburban anti-fashion attire. (See Jeans, mom. Sneakers, white). […] Even so, the fundamental question — is normcore real? — remains a matter of debate, even among the people who foisted the term upon the world.”

New York Magazine’s The Cut wrote about the new urban camouflage. HuffPost Live held a discussion on the trend. Vox wrote a normcore explainer for normies. The term snowballed into headlines at The Guardian, Forbes, and Vanity Fair, making it about more than fashion and extending it into the broader culture. Brands such as The Gap and Hanes boasted of being OG normcore. The term almost won “Word of the Year for 2014” in the Oxford English Dictionary (it tied with bae, but lost to vape). Since its coining, nearly 40,000 news stories have been written about normcore. This was all before people outside of Brooklyn were even wearing the style as a fashion statement. It was trend reporting before a trend.

The weird thing about normcore is how much of its success hinged on linguistics, rather than aesthetics. K-Hole came up with the term to mean a kind of social adaptability – dressing like a dandy at Pitti Uomo is normcore, just as it would be to wear a mohawk at a punk show. Both allow the wearer to disappear into the crowd, recognizing that “normal” is totally contextual. “Normcore was about dropping the pretense and learning to throw themselves into, without detachment, whatever subcultures or activities they stumbled into, even if they were mainstream,” explained the Times. But as soon as the word was run through the cultural machine, it metastasized. Soon, it came to refer to a particular mallcore look – Jerry Seinfeld in his garment-dyed button-ups and stonewashed jeans; Steve Jobs in his clingy, black turtlenecks and gray New Balance runners. Normcore is a kind of studied unfashionableness for the fashionable.

Part of normcore’s charm is how it doesn’t mean anything, which means it can be used for almost everything. The first half is norm, from normal; the second half is -core, meaning hardcore or extreme. The term is irresistible, puzzling, and fun. It baits people into conversations, enticing them to ask “is this normcore” or “am I fashionable now?” Like Marcel Duchamp’s urinal, it makes people reconsider what counts as stylish. It’s popularity also comes out of a poverty of language. In a British Vogue video exploring how fashion PR works, one of K-Hole’s founding members told Alexa Chueng:

People needed more vocabulary for fashion. There weren’t many words to describe how people were dressing [“Fabulous?,” Chueng jokes]. Besides fabulous. The idea of a hipster had been totally exhausted, but in my opinion, one of the reasons why the word hipster went on for so long is because there were no new words to talk about how to dress in a certain way, to have personal style, or to think of yourself as cool. I think we came into a vacuum.

Dressing normcore started off as a joke until it wasn’t one. In a Highsnobiety podcast on the etymology of fuccboi, Mary H.K. Choi talks about how fashion at the moment is defined by subversive humor, in-group winking, and memes. In 2014, shortly after K-Hole’s report was released, people were starting to get into the style as a joke, but then the aesthetic became a legitimate category. Louis Vuitton’s Kim Jones took the classic Patagonia Retro-X fleece jacket and made it lux. Birkenstocks aren’t just a fashion statement, they’ve got designer collaborations.

I think there’s something funny about what [Vetements] is able to pull off. That doesn’t mean I’m going to buy a DHL t-shirt, but I love the attitude with which it’s pulled off. I love that it feels like high-fashion trolling, which I think is always hysterical. It captures Franco Moschino’s attitude towards fashion. It shows how the people who follow these trends do it so slavishly. When there’s a spectacle like this and people buy into it, if you’re aware of what you’re doing when you buy into it, I think it becomes funny. There’s nothing more hysterical than if you bought one of those [Vetements] hoodies, put it on ice, and wore it right when it was coming out of style.

In the way the word spread like a brush fire across certain corners of the internet, normcore may be the first purely internet-created fashion trend. It’s also an example of sound branding – a strange intersection of linguistics and aesthetics, where the catchiness of a word turned the simple act of “being” into a fashionable act. Normcore is the precursor to every frump-chic style that has emerged since late 2013: dad style, gorpcore, Patagonia fleece, New Balances, track pants, fanny packs, bloated sneakers, and all things staid. For better or worse, it’s also made fashion more relatable. Whereas men’s fashion once pulled from the aspirational lifestyles of blue-blooded WASPs, Italian industrialists, and virtuous blue-collar workers, today’s icons are everyday people. One wonders if things could have turned out differently if the word wasn’t so irresistible.