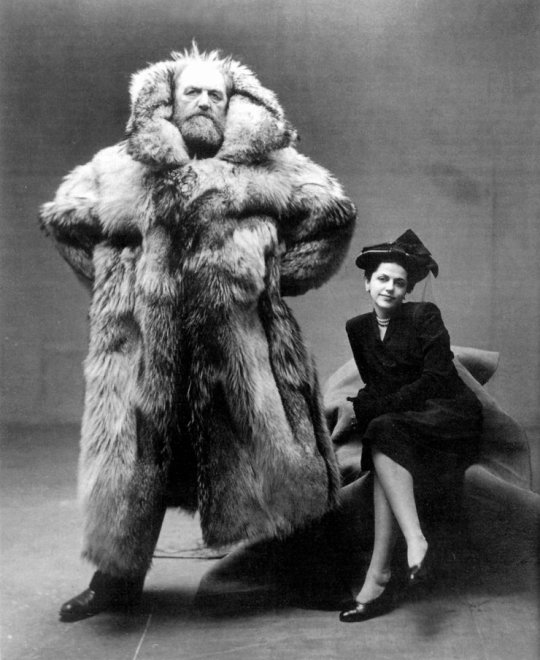

Danish explorer Peter Freuchen stood like an arctic bear when he was photographed alongside his wife in 1947. The image, shown above, made its way around the internet some years ago because of Freuchen’s magnificent outfit. Freuchen, already a giant of a man, was wearing a Sasquatchian sized fur coat – single-breasted, nearly ankle-length, with a collar so tall that it almost cleared his bald head. His wife, who was more typically dressed for the occasion, did not look amused.

Freuchen was a real-life Most Interesting Man in the World. He was a writer, an arctic explorer, and a resolute anti-fascist. During the Second World War, he fought Nazis as part of the Danish Resistance and once gave Triumph of the Will director Leni Riefenstahl the finger at a film premier. But it wasn’t the Nazis who almost killed him – it was snow. Throughout his life, Freuchen took many 1000-mile dogsled journeys across Greenland’s northernmost tundra. During one of those arctic adventures, however, he found himself caught in a particularly bad blizzard.

Hoping to wait out the storm in a snowbank, he buried himself beneath the ground’s surface, only to find that the snow above him was swiftly swirling around and turning into a thick layer of ice. Before long, Freuchen was encased in what was a frozen tomb. Quickly losing strength, he struggled for hours trying to claw his way out using nothing but his bare hands and some frozen bearskin. Freuchen had all but given up when he got an idea, which he details in his autobiography Vagrant Viking.

What a way to die! I gave up and let the hours pass without another move, but then my morale improved. I was alive, after all. I had not eaten for hours, but my digestion felt all right. I got an idea! I had seen dog dung freeze as solid as a rock in the sled tracks. Would the cold not have the same effect on human feces? Repulsed as I was, I decided to experiment. I moved my bowels and from the excrement, I fashioned a chisel-like instrument, which I left to freeze. I was patient; I didn’t want to risk breaking my tool by using it too soon. At last, I tried my chisel and it worked!

Freuchen’s escape didn’t come without a price. After being trapped for thirty hours in a coffin-sized ice cave, he crawled for three hours back to camp. I say crawl because his foot was frostbitten at that point and infected with gangrene. Upon arriving at camp, he applied at an old Eskimo treatment that striped his flesh and muscle from his bones. And then, perhaps because he was so disgusted by his skeletal structure, he decided to amputate his own toes with a pair of large pincers and a hammer (all while sober, as Freuchen was a teetotaler). The rest of his body, however, was saved because Freuchen knew how to dress for the cold. For his expeditions, he often wore densely packed fur uniforms not unlike the one you see at the top of this post.

The reason why fur works so well as an insulator is simple: animal hairs are hollow, which means they help trap heat against the skin. This is especially true of cashmere, that soft, slippery fiber that’s traditionally turned into sweaters and scarves. Since cashmere has a soft, downy feel, it allows for even more air pockets to regulate temperature. Pure cashmere doesn’t work very well for outerwear, however, because it’s dearly expensive and prone to bagging. So we have nature’s other cashmere: down. Much like how cashmere is carefully picked from the undercoat grown on various kinds of goats, down is the soft under-feathers plucked from geese and ducks. And like cashmere, down creates those necessary air pockets to help keep you toasty.

Today, the term down is often used to describe any kind of puffy garment that’s made with a filling. Sometimes that filling is synthetic (e.g. Primaloft); other times it’s natural (e.g. actual feathers). What’s the difference? Well, for one, natural down keeps it shape better over time, whereas synthetic fills can become limp, lifeless, and in need of replacement after a few years. It’s also more collapsible, which makes it easier to pack, and can wear warmer for its weight. Synthetics, on the other hand, are cheaper, more humane (no live plucking), and less affected by moisture. When natural down gets wet, the feathers collapse and lose their insulating properties.

Unless you’re fording a river, your down jacket is unlikely to get wet enough for that to be a concern. No, the real challenge is finding something that doesn’t look like a strung-up cluster of garbage bags. For the first fifty years of their history, down jackets neatly slotted into the canon of American sportswear, but much like what’s happened with hiking backpacks, they’ve somehow lost their way. Most companies today are more interested in upgrading technical features that few consumers will ever use, rather than trying to figure out how to make something look good.

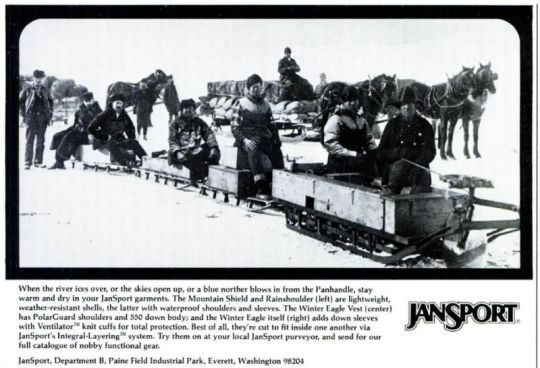

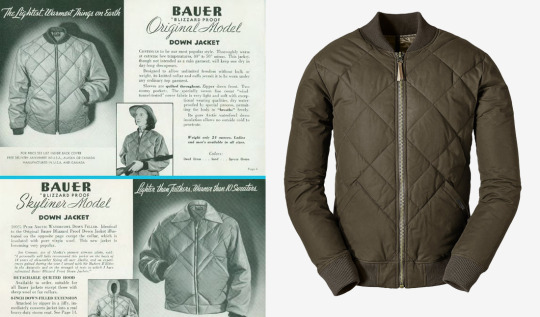

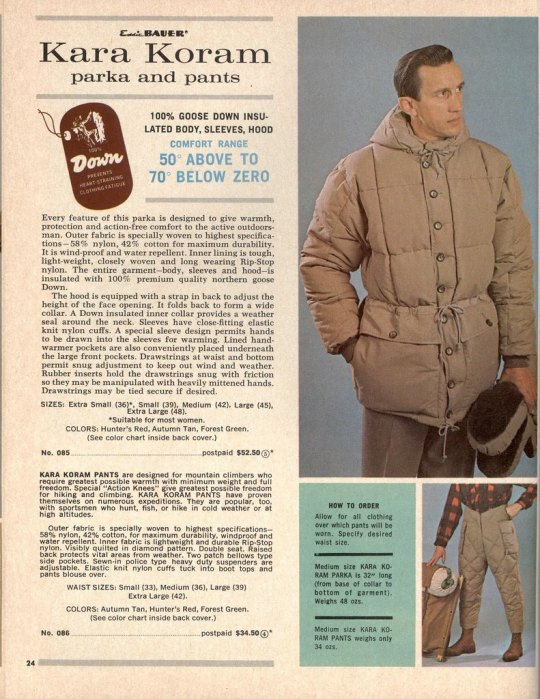

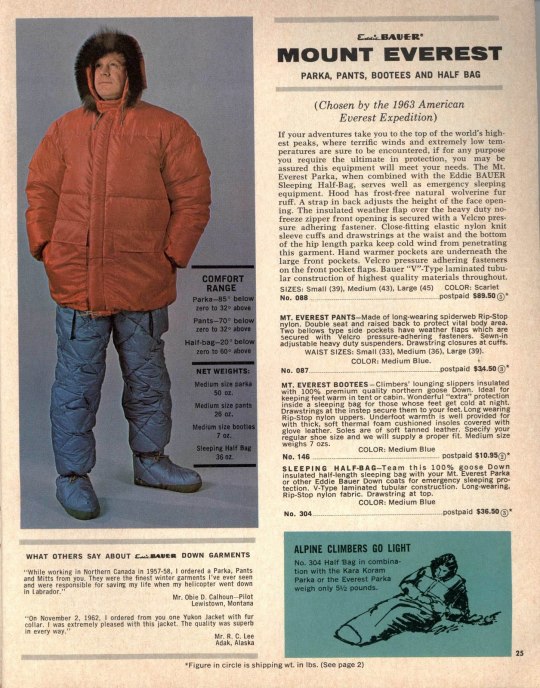

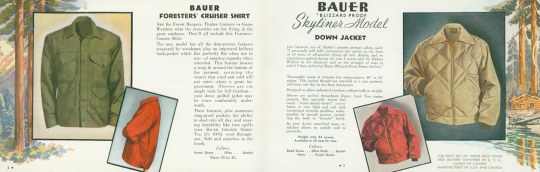

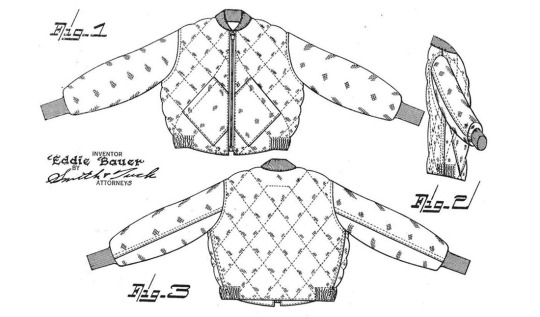

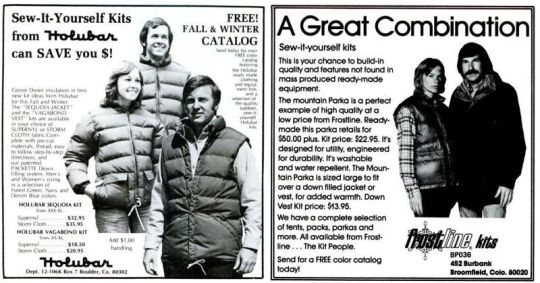

The first quilted down jacket came from Eddie Bauer. As the story goes, the company’s founder was trekking through western Washington when he put his hand on his back. There, he found his heavy, waterlogged wool coat had developed some ice. So when he got home, he set upon designing a better garment – something lighter weight, nylon-shelled, and filled with insulating feathers. The design was an instant hit for both its practicality and look. You can see the diamond quilted bomber-style jacket in the illustration above, which was submitted to the United States Patent and Trademark Office in 1936. About 40 years later, companies such as Jansport, REI, and Holubar sold DIY kits to people who wanted to build their own puffy vests and parkas at home.

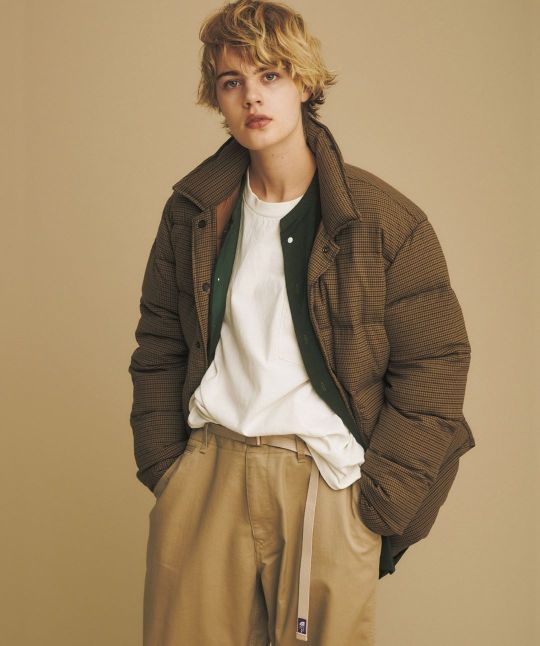

Many of these outdoor styles go well with the kind of gruff Americana that the Japanese charmingly call Rugged Ivy or Heavy Duty. In the 1970s, Men’s Club columnist Yasuhiko Kobayashi noticed that American university students were trading their blue blazers and tweeds in favor of repurposed outdoor gear – 60/ 40 mountain parkas, Champion sweats, and climbing boots (Youngsam, owner of Seoul’s The ResQ shop, has some nice down outfits on Instagram). David Marx writes about the look in his book Ametora.

While the rustic Americana of Heavy Duty looked very different from the polished Americana of Japan’s 1960s Ivy boom, Kobayashi believed that Heavy Duty and Ivy were two sides of the same coin. Inside the Ivy system, students wore blazers to class, duffle coats in winter, three-button suits to weddings, tuxedos to parties, and school scarves to football games. Inside the Heavy Duty system, men wore LL Bean duck boots in bad weather, mountain boots when hiking, flannel shirts when canoeing, collegiate nylon windbreakers in spring, rugby shirts in fall, and cargo shirts when on the trail. In the introduction to his standalone Heavy Duty Book, Kobayashi wrote: “I call Heavy Duty ‘traditional’ because it’s the outdoor or country part of the trad clothing system. You could even say it’s the outdoor version of Ivy.”

You can still track down some of these coats, but it takes some hunting. Instead of modernized brands such as Canada Goose or Moncler, try Patagonia and LL Bean. Eddie Bauer still makes their iconic Skyliner, but it’s been slimmed up to suit modern tastes. I prefer the roomier, rounded bodies on vintage versions.

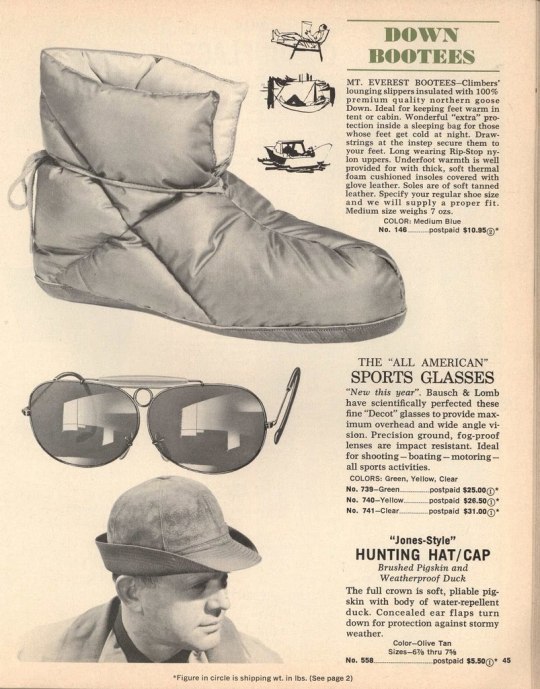

Vintage is also the way to go if you’re on a budget. It’s easy to find goose down vests and parkas for under $100, and their patina only adds to their charm (there are even quilted pants!). Saunders Militaria has one of the best collections of vintage down outerwear I’ve seen anywhere, although he mostly specializes in rare and expensive pieces. For something new, Abercrombie & Fitch has two surprisingly handsome models with a slight vintage flavor. You can also layer this mountaineering vest under your usual outerwear for just a little more than $200.

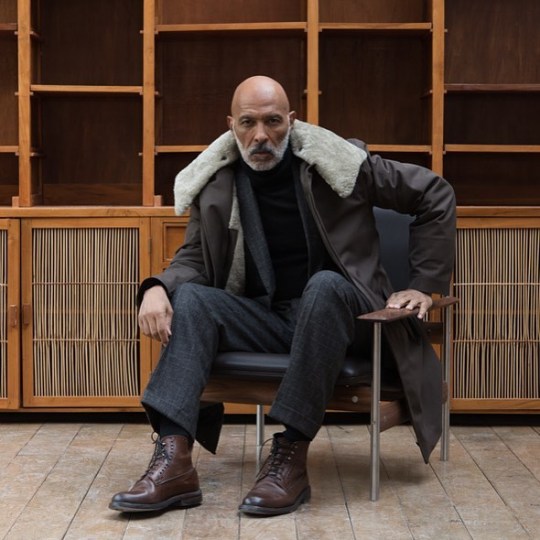

If you have a little more coin to spend, check the companies that have always supplied solidly made, vintage-styled Americana sportswear. Crescent Down Works, Rocky Mountain Featherbed, Battenwear, Stevenson Overall Co., Monitaly, Kaptain Sunshine, American Trench, and Burgus Plus are among my favorites. I also like Ten C, Norwegian Rain, Margiela, Document, Mackage, and Aime Leon Dore for something a little more contemporary. It would be hard, for example, to get a better-built, modernized parka than Norwegian Rain’s Moscow.

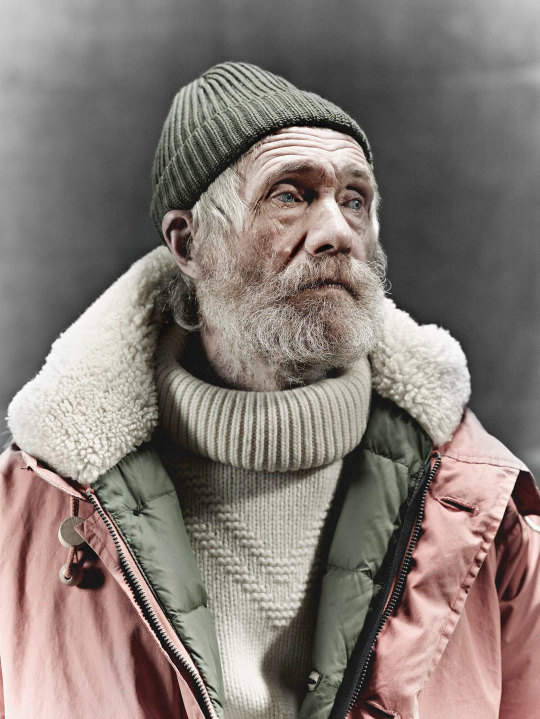

Far and away, my favorite down outerwear is from Nigel Cabourn, pictured above. Years ago, Cabourn made a parka modeled after something Edmund Hillary wore on his first successful ascent up Everest in 1953. His version, simply called the Everest, has since become his most famous piece of outerwear. It has all the same detailing as Hillary’s original, but is made with modern workmanship. The shells are typically made from weather resistant Ventile. The three-panel, snorkel hood features a warm sheepskin lining and fur trim. And both the body and pockets are stuffed with 700 fill goose-down insulation (fill power measures the down’s loft). The coat feels like you’re wearing a cloud and an electric blanket at the same time, making you impervious to the cold. I bought one a few years ago, and while I admit it doesn’t get that much wear in California, I appreciate it when the chill surprisingly sweeps down in the middle of winter. Plus, I can say I haven’t had to chisel my way out of any ice caves with frozen poop.