The first leather jacket I ever bought was an Enrico Mandelli bomber. It’s made from a soft cotton lining and even softer lambskin, with just enough fullness to stay true to the garment’s origins, but is also slim enough to go with tailored trousers. Like many men trying on a leather jacket for the first time, I hemmed and hawed, tugged at my fronts and cocked my head, wondering if I was really a “leather jacket kinda guy.” Well, since then, I’ve acquired about fifteen more pieces, ranging in styles from a Schott Perfecto to the very contemporary Margiela five-zip. Nothing in casualwear can be rightly called a wardrobe essential, but a leather jacket comes pretty darn close.

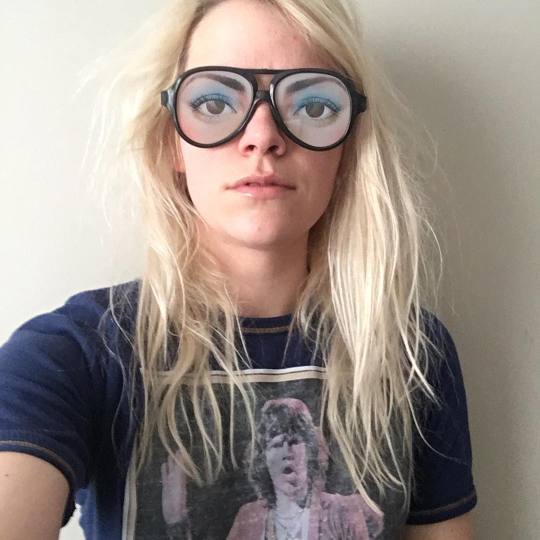

Among leather jacket makers, few are as unique as Atelier Savas. The company’s founder, Savannah Yarborough, studied menswear at London’s Central Saint Martins, and then returned home in 2010 to work as the senior designer for Billy Reid (you may have heard of the label). In 2011, she designed one of the brand’s best-selling jackets, a cropped double rider made from of a crinkly tobacco leather. Then, a few years ago, she struck out on her own and started Atelier Savas, a bespoke tailoring company for unconventional leather outerwear. Her company will one day be seen as a pioneer in bespoke tailoring trade or it’ll go down in flames because it’s sitting somewhere out in no man’s land.

To understand Atelier Savas, you have go to back to the beginnings of the American garment industry. We take ready-made clothing for granted today, but in the long history of men’s dress, it’s a relatively new invention. Up until about the American Civil War, most men had their clothes made for them, either by a tailor, if they could afford one, or by wives and mothers working from home. The only ready-made clothing at this time was workwear, which was often crudely constructed for sailors, miners, and slaves.

This all changed sometime in the mid-19th century. The American Civil War created a demand for mass-produced uniforms and the industrial revolution made standardization possible. This transformed the head cutter at tailoring shops – the person who drafted and cut a client’s paper pattern – into the industrial role of a pattern maker (a person who drafts patterns not for one, but the many). During these early days of the American garment industry, pattern makers served both as technicians and creatives, helping to make the suits and sport coats that men across the country relied on.

After the Second World War, with the energy of a booming middle class, a nascent sportswear industry found it needed to split the role of a pattern maker into two distinct roles – that of the designer, who simply designs, and that of the pattern maker, who translates those designs into technical specifications. Today, that split is so complete that few designers have any technical ability. Likewise, pattern makers often don’t have the taste necessary to design commercially successful garments on their own. In an interview at The Parisian Gentleman, Bruce Boyer once wrote of this watershed moment:

With the end of WWII, this new group of designers (most of whom had cut their teeth in women’s wear) tentatively entered the menswear market and found some purchase, enough that a second generation began to emerge by the mid-’60s – some of whom had absolutely no connection to women’s wear, sometimes not even to design training. By the early ‘70s there were both Ralph Lauren and Giorgio Armani, not to forget Geoffrey Beene, Perry Ellis, Stanley Blacker, Jeffrey Banks, Pietro Dimitri, Carlo Palazzi, Tommy Nutter, Michael Fish, and a growing number of even younger designers hot on their heels. Clothing labels now began to make that telling switch from manufacturer’s names to designer’s names. The designer in menswear had arrived.

Ready-to-wear today has never been more aesthetically interesting, thanks in part to the emergence of the designer as a purely creative role. Before the 20th century, ready-made clothes were little more than watered down imitations of their better custom-tailored counterparts. But in the last seventy-five years, fashion has exploded with energy and imagination. Since the 1960s, clothes have become more novel and daring, rather just trying to achieve “class perfection” in craft.

Traditional bespoke tailoring, on the other hand, remains as a fairly conservative business. Part of this is just about the world in which it operates – the men who commission custom clothes are usually doing so for work – but it’s also about the process. Ready-to-wear not only often benefits from having an experienced designer, but the clothes are also made through an iterative sampling process. A sample garment is made and then remade until the designer is happy with the outcome.

With bespoke tailoring, you’re working on just one garment – the one that will be delivered – and it’s often a suit or sport coat, which is adjusted on the margins. Customers are wise to stay close to the basic template, which is a result of decades of practice and experiment, as well as the collective ideas of many skilled minds and hands. This is why, when you go bespoke, suits and sport coats can look fantastic, but even moderately innovative designs, such as safari jackets, can lack verve.

Atelier Savas is one of the few companies that’s trying to bridge the gap between these two worlds. As a Central Saint Martins graduate and former Billy Reid menswear designer, Yarborough has the eye and expertise necessary for more forward facing creations. At the same time, her company specializes in bespoke leather jackets, all done in the most traditional of craft methods.

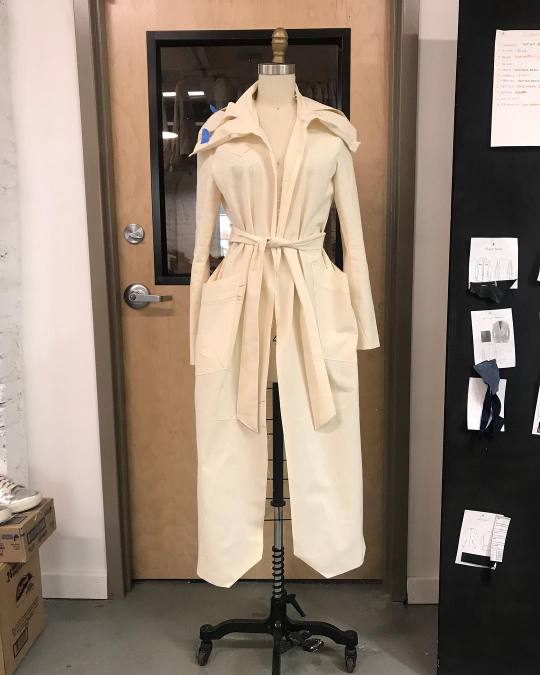

The process of making a bespoke leather jacket isn’t too different from what happens with a suit or sport coat. Measurements are taken; paper patterns are drafted; materials are cut; and the garment is then sewn. The two biggest differences: since leather will show holes from where a needle has passed, Yarborough conducts her fittings using toile (a cheap, unbleached cloth used to make sample garments). You’ll occasionally see toile in men’s tailoring. Charvet uses it for making certain dressing gowns and shirts, and sometimes English tailors will use it when working with particularly expensive fabrics. Most of the time, however, it’s reserved for women’s haute couture.

Interestingly, whereas many bespoke tailors, including those on Savile Row, have switched to using block patterns, Yarborough insists on drafting everything from scratch. “I’m somewhat of a traditionalist, in a weird way,” she says. “I feel that bespoke means the garment was created specifically for you. If a garment was created off a block pattern, I don’t feel it’s really bespoke.”

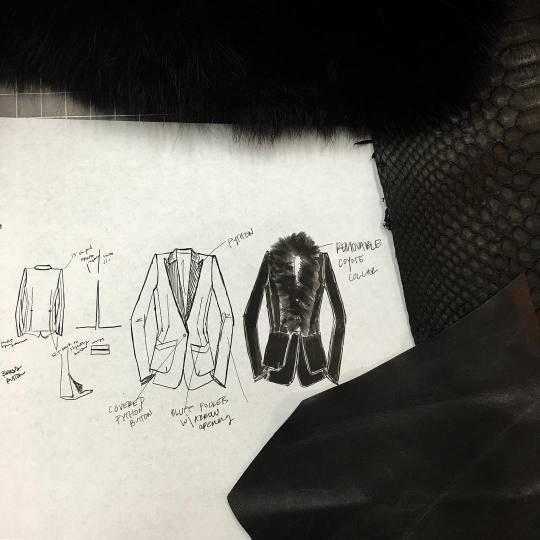

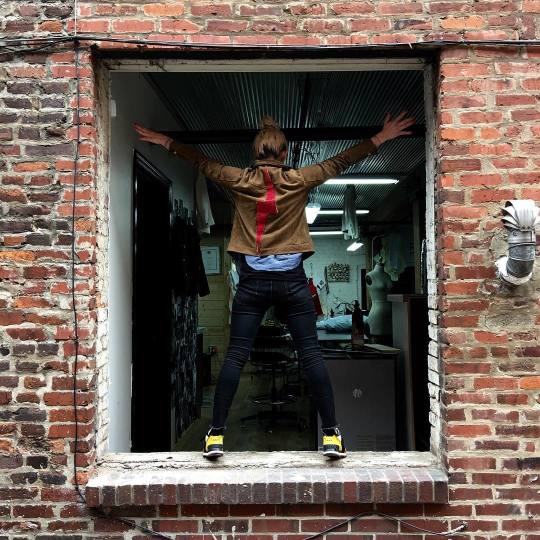

Yarborough’s designs, however, are anything but traditional. This is where she leverages her skill, experience, and education as a menswear designer, playing with proportions and detailing. In the photos immediately below, you can see a leather jacket she made with a heavily dropped front balance, such that the jacket dramatically slopes down from the back. She also incorporates washing and distressing into her finishing techniques, which is something you’d never see on Savile Row.

She says much of this process starts with having a conversation with the client, talking them through how the various leathers will age, getting to know their lifestyle, and showing them the different sample jackets in her showroom. “Those are just a jumping off point,” she says. “Sometimes a client will come in with an idea of what they want and they’ll have a ton of photos from magazines. Other times, they trust me to put them in something. But it’s about getting to know the person and guiding them into a realm they may have never been in, or think of things they never thought of.”

Of course, that process has its ups and downs. In exploring such new territories, a customer risks not actually liking the jacket in the end – these are often inventive leather jackets, after all, not your standard suits and sport coats in blue or gray. But Yarborough says she tries to mitigate that with multiple fittings using fully detailed canvas jackets. “Sometimes a customer will say they want to look like David Beckham in some Tom Ford ad. And I’m like, ‘yea, I want to look like David Beckham too, but this jacket isn’t going to look good on you,’” she explains. “So I’ll do a fitting jacket, fully detailed, with their preferred hardware design on one side and my suggestion on the other side. This way, they can compare the two outcomes.”

In talking with Yarborough, I was struck by how many challenges her business faces. Since she’s effectively working in the world of high-end fashion design, her discussions with a client have to be more in-depth than what a traditional bespoke tailor will engage in. At the same time, she’s also unable to create the kind of lookbooks that ready-to-wear brands depend on since each commission isn’t necessarily indicative of what a new client will receive. Every project is a unique one-off and customers aren’t always keen to be being photographed. Her “house style” has a sort of tussled, Southern, country rock charm, but that can take many forms.

She also carries all the burdens of a traditional bespoke business – the difficulty of scaling up, the need to explain to customers why bespoke is worth the money, and finding new customers at a time when people want things immediately, not months from now. And whereas as a traditional tailor can rely on a client’s already drafted pattern for subsequent commissions, Atelier Savas is complicated by the fact that projects can be completely different from one to the other. A lambskin double-rider, for example, will require a completely different pattern than a long shearling coat, even if both are built for the same person.

“Pattern making is tricky when you’re working with leather because the material behaves differently than a fine woolen,” she says. “There are lots of things you have to consider, such as the bulk points. When you have a collar meeting a zipper, that can be up to six layers of material, so you have to adjust the points of contact to make sure everything looks right. Shearling is also a lot bulkier than a lambskin, so that requires a new pattern. And for a suit jacket or sport coat, you may only have your front, side, and two back panels. With casualwear, a lot of the design is in the paneling and seaming, so a new design may require different pattern pieces.”

Suits are rapidly become like women’s wedding dresses – something you wear once for a special occasion, and then never again. If traditional bespoke craft is to survive, it may have to be through this new casualwear space that combines traditional craft with forward facing designs. It’s hard to say what’s the real advantage of bespoke casualwear, as weekend clothes can be more forgiving and consumers are already drowning in options, but I imagine the best customer for this is one who appreciates craft for its own sake. I’m an easy fit in ready-to-wear shoes, but my favorites are those I had made through Nicholas Templeman. There’s something special about an item that was made just for you, beyond any material benefit you could get through fit and styling. It’s the psychological comfort of knowing you have exactly the right thing.

Those interested in Atelier Savas can catch them at their trunk shows. At the moment, they visit Los Angeles and New York City. They also have a showroom in Nashville, and last year, they introduced a more affordable made-to-measure service. Yarborough says she’s also testing out some other MTM ideas this year, but being such an innovative business that sits at the intersection of ready-to-wear fashion and traditional bespoke, there are some kinks to work out. “I feel like we’re out on Mars,” she laughs.