Back in 1996, Tom Junod wrote a piece for GQ Magazine, which was nominated for a National Magazine Award. Simply titled “My Father’s Fashion Tips,” it was about his father’s impeccable style, as well as the opinions of a man who felt strongly about clothes. The article is a wonderful read, and even includes some rules for underwear, but the best part is his father’s unwavering confidence that a turtleneck is the most flattering thing a man can wear – an inflexible and enduring axiom that, Tom writes, his father believed in more than the existence of God.

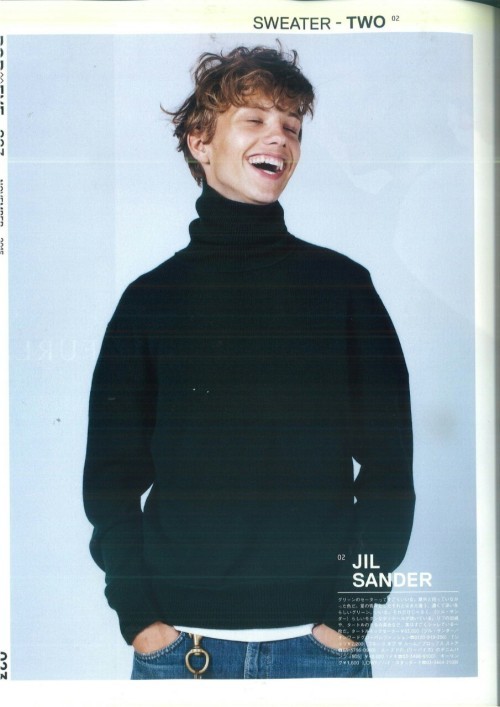

Anytime my father wears a turtleneck, he is advancing a cause, and the cause is himself. That is what he means when he says that an article of clothing is “flattering.” That is where his maxim extolling the turtleneck acquires its Euclidean certainty. The turtleneck is the most flattering thing a man can wear because it strips a man down to himself – because it forces a man to project himself. The turtleneck does not decorate, like a tie, or augment, like a sport coat, or in any way distract from what my father calls a man’s “presentation;” rather, it fits a man in sharp relief and puts his face on a pedestal – first literally, then figuratively. It is about isolation, the turtleneck is; it is about essences and first causes; it is about the body and the face, and that’s all it’s about; and when worn by Lou Junod, it is about Lou Junod.

Every year around this time, fashion writers try to convince us that the turtleneck is, in fact, finally coming back. You can take this to mean that they are always in style or never quite in, although it’s probably a mix of both. Turtlenecks teeter on the edge of men’s closets. They’re viewed with as much suspicion as they are with interest.

Turtlenecks are favored for their age-masking properties (“Our faces are lies, but our necks are the truth,” Nora Ephron wrote in I Feel Bad About My Neck), as well as their associations with intellectuals and counterculture types. At the same time, it’s impossible to deny their slight ridiculousness. They come up to your chin, potentially masking your jawline, and vaguely look like a sweater with a built-in neck brace. In The Mystery Guest, Grégoire Bouillier says high-necked sweaters are a mark of “pseudo sportsmen with, as they say, the lamest kind of collar.” Diane Keaton extols their virtues in her second memoir, Let’s Just Say It Wasn’t Pretty. “Turtlenecks are particularly underrated. Buy one, I dare you. […] Turtlenecks cushion, shield, and insulate a person from harm.” A few sentences later, however, she warns: “If it turns out that you begin to wear turtlenecks as often as I do, and you’re my age, and you’re not Cary Grant, you will run the risk of receiving a fair amount of criticism.”

If you want to know how the turtleneck is commonly viewed today, don’t turn to the trimly militant one Steve McQueen wore as a sleuth in the 1968 thriller Bulliet. Or ones Richard Roundtree paired with long leather coats in Shaft. Instead, look to more modern references. The turtleneck is at the center of countless comedy scenes, including ones from SNL, Seinfeld, Dinner for Smucks, and Will Ferrell’s parody of the 1970s. When hip hop star Drake danced to the beat of his own drum machine in “Hotline Bling,” he was mocked not only for his awkward dad-moves, but also the slouchy gray lambswool knit that came up to his beard. And whatever Steve Jobs has done for the black turtleneck has surely been undone by Elizabeth Holmes.

Part of this is about how men are deathly afraid of sticking out. In a business-casual world where crew- and v-necks dominate, the turtleneck betrays effort, spoiling the purposeful nonchalance advocated by Beau Brummell. “It’s hard for me to think of something sold at The Gap as controversial. But! I can definitely imagine a guy wearing a turtleneck to work one random Wednesday and becoming ‘The Turtleneck Guy,’” says Rachel Tashjian, Deputy Editor at Garage. “I wonder if because the turtleneck came to be so closely associated with the political left, artists, and Europeans in the mid-century, it hasn’t quite shaken that bohemian edge and somehow remains a statement.”

Emilia Petrarca, Fashion News Writer at The Cut, agrees. She’s a staunch advocate of the style for women, noting that it makes for a great first-date outfit (“They’re soft and clingy and warm, and they keep you snug emotionally, too”). But when asked how she feels about turtlenecks on men, she hesitates. “Sometimes men look like dinguses in turtlenecks,” she admits. “If worn with round glasses and a copy of Foucault, a turt can make a man look like a liberal arts freshman. If worn with jeans and New Balance, he drank the Silicon Valley Kool-Aid and probably wants to talk to you about the Bitcoin bubble. It’s just so easy to fall for a stereotype.”

TURTLENECKS AS ATHLEISURE

The turtleneck might be one of the earliest examples of athleisure in the 20th century. Or, at least, how fashion influence has generally come from the bottom-up, rather than trickled down. In the period following World War I, men’s style was obsessed with sport and outdoor activities, such as hunting, fishing, and skiing. These were the kind of things that allowed clothiers such as Abercrombie & Fitch to rise to prominence. This was also the start of sport coat culture, as Ivy League undergraduates wanted separate jackets for spectator sport. And when discharged veterans returned home from serving in the distant trenches of Europe, they raided haberdashers for things that made them look smart, but also casual.

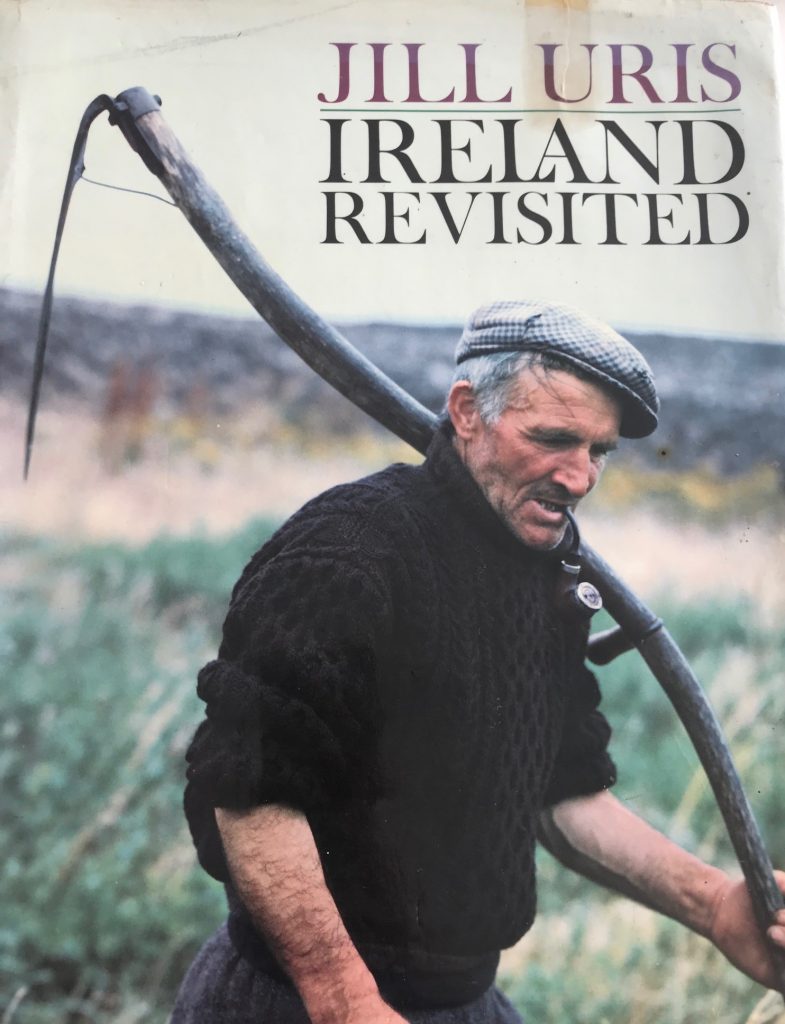

Noël Coward is often credited with being the first to make the turtleneck a fashion item. In his memoir, Present Indicative, he wrote that he turned to them “more for comfort than effect” (“blithely sliding past the fact that the simple show of privileging comfort invariably creates its own effect,” Troy Patterson notes). But it was men’s obsession with sport and utility during this time that made such an item possible. Fishermen, particularly of Scottish, English, or French heritage, wore high-neck collars while working in or around the North Sea, giving the style some credibility. And for a time during the late 19th century, the style graduated to sport and became associated with bicycling, tennis, and polo (perhaps why this is sometimes known as a polo neck). In an old article on turtlenecks, Bruce Boyer says that, “for most of its life it’s had this dual image of a street-smart tough on the one hand, and an aesthete on the other.”

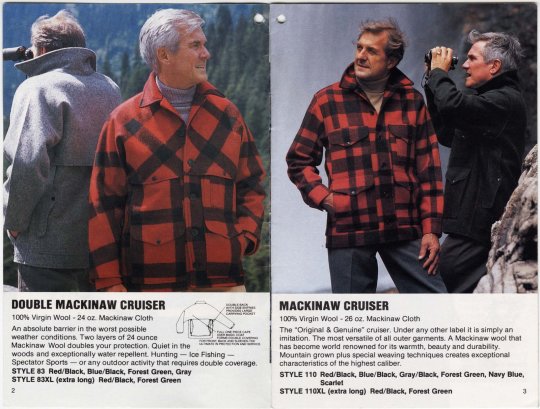

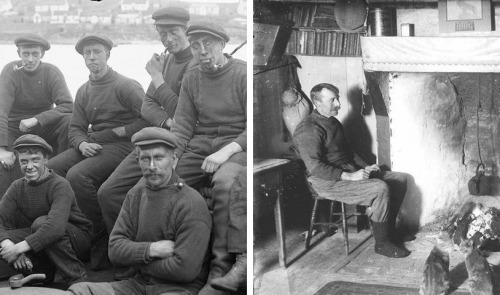

This utilitarian aspect never left the turtleneck in fact or symbol. Many World War II sailors who fought the Battle of the North Atlantic were terribly glad for their thick wool turtlenecks and watch caps during long, dark, penetratingly cold nights on deck. We see them at the rail, the dark top of the sweater peeking out from the pea coat, binoculars slung ‘round the neck. […]

The archetypal post-WWII beatniks made the black turtleneck sweater a part of their daily outfit that included various berets, goatees, jeans, army surplus khaki trousers and field jackets, dark glasses, and bongo drums. In Steven Watson’s The Birth of the Beat Generation, there is a wonderful photo of a young William Burroughs standing in an alley outside of his home in Tangier (which he called the Villa Delirium, “the original anything goes joint”) wearing most of the requisite gear, including a black turtleneck sweater.

This was, in fact, only a slightly extreme version of what many university students – many of them ex-soldiers – here and in Europe were wearing every day to their classes: Army-Navy surplus khakis, duffle coats, and turtleneck sweaters. At France’s Sorbonne, New Wave bohemianism dictated black leather jackets, as postwar existentialism expressed itself sartorially as anti-fashion among educated youths. The baggy and oversized turtleneck became a symbol of the young intellectual, worn with wide-wale corduroys and thick brogues. The outfit was thought to show rebellion with those in power and solidarity with the workingman, as the New Left began to emerge. Sartre wore his turtleneck under a workman’s jacket, Camus preferred a trench coat.

The turtleneck today can be challenging to wear, but it’s the closest thing you’ll get to putting your face on portrait mode. The high collar throws a face into high relief; it accents an outfit’s academic or workwear undertones. It’s also an excellent substitute for a tie when you’re trying to make a suit look more natural. (Instead of people asking you why you’re wearing a suit today, they’ll now just ask why you’re wearing a turtleneck).

Bruce tells me he likes them with more country-type suits, such as those made from covert cloth or whipcord. “When I was a young man and single, I used to fly off to Europe with a tweed jacket, turtleneck, corduroy trousers, and chukka boots. That outfit served me just fine for touring around any place, day after day,” he says. “I think they’re a classic item that tends to go in and out of popularity and fashion, but not out of style.”

Rachel adds that she thinks the style implies effort, eagerness, and good grooming. “I think of it as a prep school basic – the kind of thing a really preppy woman wouldn’t let go of after getting out of college, and somehow it becomes a staple or even, in the case of the great Diane Keaton movie Something’s Gotta Give, a security blanket. (Remember that Jack Nicholson cuts it off when they first sleep together!) It’s a conservative garment for women, and a lightning rod for men. I love that about it.”

Indeed, there’s something preppy about a turtleneck. The style was listed as a wardrobe staple in The Official Preppy Handbook and seems like the sort of “sensible” sweater a wholesome, catalog-model family would wear while going somewhere in a station wagon. “I think men are just afraid of looking at all soft, literally and figuratively speaking, which is a shame,” Emilia says. “Turtlenecks remind me of my dad. When he was alive, he wore beautiful, Italian-made turtlenecks all winter long. I think dads are cool with embracing their softness. They know what’s good.”

HOW TO WEAR

I’m not as pro-turt as Lou Junod, but I like them more than plain v-necks. They’re distinctive, to be sure, but in a way that’s almost necessary if you want to assert any style these days. And you don’t have to wear them in the sleazy 1970s manner (although, you can). Some ways to wear a turtleneck this season without seeming pompous of forced:

Chunky or Thin: When it comes to weight and gauge, a lot depends on how you plan to wear the sweater. Slimmer sport coats will require a thinner one- or two-ply knit, likely with fitted shoulders and a soft merino or lambswool construction. Roomier jackets, on the other hand, can be worn with either chunky or thin knits.

That said, I generally find chunky turtlenecks to be more versatile. “Chunky certainly has a Maine Guy attitude, while thin will get you closer to that bohemian, intelligentsia energy,” says Rachel. On the downside, since a turtleneck is basically a sweater with a built-in scarf, a thick one can wear uncomfortably hot once you’re indoors. Bruce, who’s much more sensibly practical, prefers thinner versions. “The chunky ones, the Aran sweaters et al, look very broth-of-the-heather. But they work better on an open boat in the North Atlantic, you can’t wear them indoors with central heating. Today most buildings are overheated.”

Color: My friend Pete at Put This On notes that “navy is the easiest and most forgiving color to wear, but grays, burgundys, and greens are good matches for fall-toned sport coats as well.” Over the years, however, I’ve found I mostly rely on a thick and chunky cream turtleneck, then mid-gray or charcoal thin versions when I need something more comfortable. If you’re going for something you can wear with a casual suit or sport coat, try a lightweight turtleneck in a tartan green cashmere, lambswool, or merino.

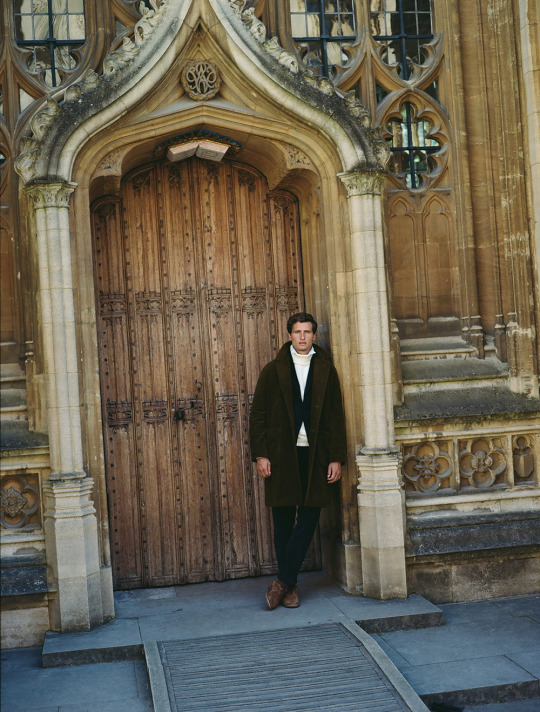

Outfit Pairings: Turtlenecks look most at home with suits and sport coats in wintery materials such as woolen flannel. “Just the other evening I attended a book signing party for Stephen Pulvirent’s new book The Watch, and he was wearing a terrific covert-cloth suit with a cashmere turtleneck,” says Bruce. That said, these sorts of outfits have an academic air, which may or may not be your thing. To tone it down a little, you can try a turtleneck with a slightly chunkier ribbed collar, but a still manageable two-ply body.

I prefer turtlenecks in more casual outfits, particularly with topcoats or jackets that feature a distinctive collar. See George Wang of BRIO above, who’s shown wearing a cream-colored knit surrounded by the corded collar on his waxed cotton Barbour. They also work with shearling jackets (although mostly in thin knit varieties, as shearling is already a bit bulky). If you hover over the photos at Mr. Porter’s section for turtlenecks, you can see how they’ve styled their models.

For more outfit ideas, go back to the turtleneck’s history without being too literal. The style works well with rugged items that similarly draw from sport and outdoor activities, even if it means a refined tweed sport coat. Samuel Beckett is a great style inspiration in this regard. Wear them with denim jeans or whipcord trousers, hooded duffle coats or sherpa collared bombers. Looser, non-clingy knits will make you look at ease, while trimmer, thinner styles convey a sense of discipline and rigor.

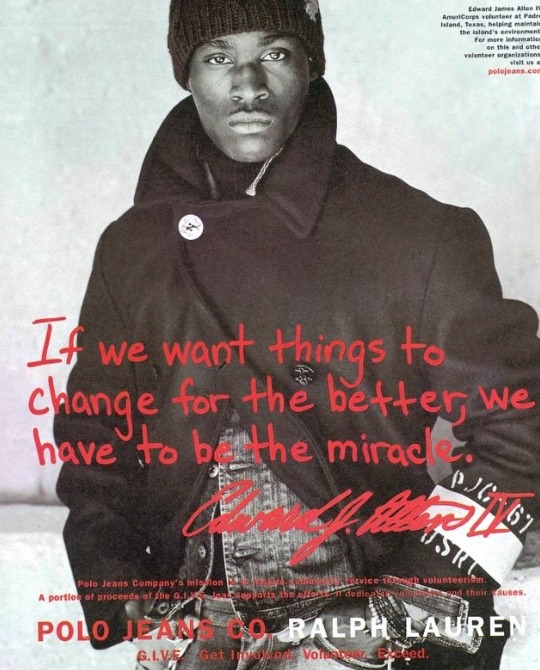

Where to Buy: Many of the usual suspects for recommendable knitwear will have turtlenecks. See Inis Meain, Drake’s, The Armoury, John Smedley, Harley of Scotland, and ESK Knitwear. East Harbour Surplus and Ralph Lauren have some lovely cream-colored versions this season. North Sea Clothing and SNS Herning are good for something more distinctively casual and workwear-inspired. GRP, 18 East, De Bonne Facture, and Incotex are also worth a look.

For something more affordable, check Uniqlo for thin merino turtlenecks and Orvis’ Royal Air Force Crew for something heavier. Between a cream-colored turtleneck and something darker, you’d have all your bases covered here for less than $200. I’ve also been impressed with the quality of Club Monaco’s non-cashmere knits. I’m not crazy about the racing stripe on this season’s turtleneck, but it would remain mostly hidden when worn. Berg & Berg is also good for this sort of thing. At $225, their sweaters aren’t cheap, but the company generally offers solid value for their prices. If at any point you feel self-conscious in your turtleneck, just pull the collar up and over your head. The high-neck style is perfect for soothing anxious introverts.