Everyone in menswear seems to believe his part of the world is in decline. Ivy Style’s Christian Chensvold, for example, yearns for a preppier past, when Brooks Brothers still made proper button-downs. A Continuous Lean’s Michael Williams romanticizes a time when America still had manufacturing. The Art of Manliness’ Brett McKay is trying to revive traditional masculinity. And StyleZeigeist’s Eugene Rabkin can’t seem to find one good thing about designer fashion. For him, clothes are hurtling towards greater superficiality, hype, and crass commercialism. In a Business of Fashion op-ed about how “fashion has become unmoored and lost its original meaning,” Rabkin is so down and depressed, he can’t even get worked up about his own indictment. He dispiritingly ends his essay with: “In other words, whatever.”

Samuel Huntington calls such writers “declinists” for how they assert things are getting worse. He was talking about weightier matters than men’s trousers, but the idea of an earlier, better time runs deep in the history of Western intellectual thought. In his book The Idea of Decline in Western History, Arthur Herman outlines the long shadow of Western pessimism. “While intellectuals have been predicting the imminent collapse of Western civilization for more than 150 years, its influence has grown faster during that period than at any time in history,” he notes.

Herman starts his book with 19th century thinker Arthur de Gobineau, who resigned himself to the idea that the Aryan race would one day be tragically “contaminated” through its contact with the Latins, Gauls and other “lower orders.” He then moves on to declinists of every stripe, “from philosopher-pessimists such as Friedrich Nietzsche and Michel Foucault, cultural pessimists such as Henry Adams and Brooks Adams, and historian-pessimists such as Oswald Spengler and Arnold Toynbee.”

Whether they were ancient Greek philosophers or modern eco-pessimists, Herman’s cynics were united in their hatred for modern society. For declinists, modernism erodes community life and personal virtue, it levels high-culture and elevates the profane. The tackiness of capitalism deadens the soul and reduces everyone to being a cheap, rapacious consumer. As Andrew Carnegie put it, “capitalism is about turning luxuries into necessities.”

If these themes sound familiar, it’s because you can’t escape them even when reading about clothing – society has never been worse, clothes used to be better, and so forth. But declinism is a trick of the mind where we remember things to be better than they were. As Fareed Zakaria wrote in his “optimist’s lament” for The New York Times:

Beneath [declinism] lurks a familiar romanticizing of the world as it is imagined to have existed before rapacious capitalism and its ideological handmaiden, individualism, got to it. We forget how squalid was the life of rural peasants, who around the world still jump at the chance to escape their coherent, organic lives; how stifling those warm, fuzzy communities of yore really were; how limited was that world of high culture and patrician society (a nice life if you could get it!). Above all, we forget how the rise of capitalism and Enlightenment liberalism freed up the life of the ordinary human being.

IS IT ALL GOING TO PITS?

What has fashion done for the life of the ordinary human being? And is it doing less than it was before? When was the Golden Age of style?

To determine this, you have to go back to the root of today’s fashion system – the golden mile in London known as Savile Row, which tailored clothes for men, and Paris’ haute couture system, which similarly made dresses for women. Both attracted attention from around the globe, and imitators in both large-scale manufacturing and small-scale tailoring. For much of their tailoring history, Italy and Hong Kong looked to London for direction. For instance, Rubinacci, the leading bespoke tailoring house in all of Southern Italy, started with the name London House.

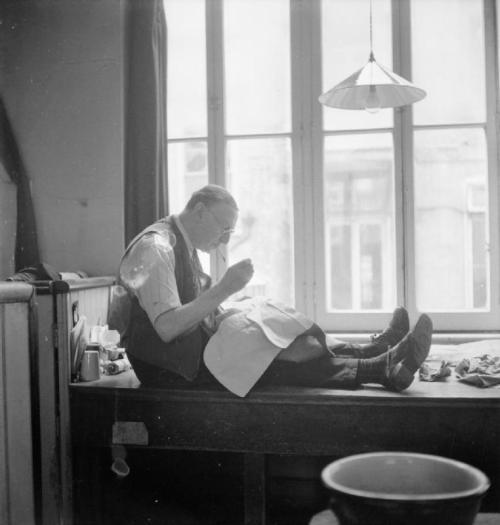

However, over the last hundred years, this system of production has been slowly displaced by ready-to-wear. In the 1960s, it was still possible for a Parisian fashion house to survive on haute couture alone. By 1975, custom clothing accounted for no more than 18% of direct profits (excluding perfumes). In 1985, that figure was down to 12%. Employment has seen a similar decline. Before the war, Chanel employed 2,500 people for its custom orders; Dior about half that. By 1985, all of the twenty-one remaining houses labeled “Couture Creation” collectively employed a total of 2,000 people – not even the number employed by Chanel alone just thirty years prior.

During this time, Parisian couture produced clothes for no more than 3,000 women around the world; London’s West End and Savile Row numbers were not that far off. “The U.K. was a mess during the 1960s and ‘70s. As the rest of Europe was building the European Union, we were busy losing the battles in Suez and clinging on the last remnants of our empire. Until we entered the EU, we were ‘the sick man of Europe,’” says bespoke shoemaker Nicholas Templeman. “Eric Lobb’s trips to the United States saved the family’s shoemaking firm, John Lobb, while others in the West End were shutting down or getting bought up.” A similar story is reflected at Anderson & Sheppard, where the firm’s Managing Director, Colin Haywood, tells me the company would have closed in the immediate post-war years if it weren’t for their overseas trips. Many of London’s best tailoring and shoemaking firms at this time were just getting by.

OUT OF A COMPOST HEAP, A THOUSAND FLOWERS BLOOM

One of the paradoxical developments in the decline of custom clothing is that, as sales shrank, creativity boomed. Haute couture no longer just produces the latest fashion for women, and it would be hard to characterize it as either classical or avant-garde. Instead, it has survived by marrying traditional craft with aesthetic gratuitousness. Having shed its earlier commercial obligations, couture now transcends fashion and has firmly planted itself in the world of art. The dresses Rihanna has worn to various Met Galas, for instance, were produced for the pride of craft and the admiration of an attentive audience, and never intended for everyday wear.

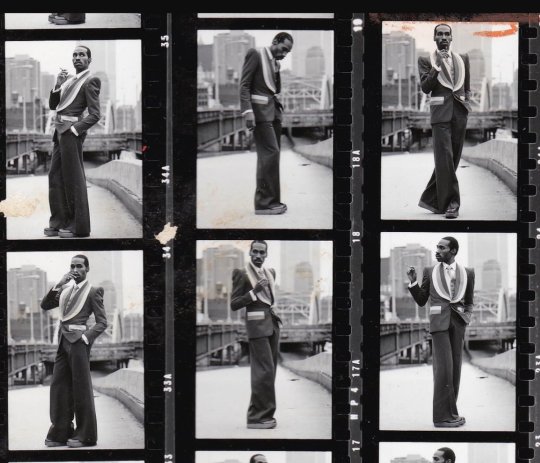

Similarly, Tommy Nutter and Edward Sexton, working together under the banner of Nutters of Savile Row, introduced the uproarious and imaginative style of the 1970s. Nutter took the English hacking jacket – a long, full bodied, horse riding jacket traditionally only worn by the aristocracy – and made it into a fashion item. Their jackets had wide, wingspan lapels; the skirts flared out to give the jacket an X-shaped silhouette. For those who wanted to amplify an already loud look, suits were made from bold plaid fabrics, taped edges, and patch pockets cut on a bias.

If you’re not familiar with name Nutters, you’ve certainly seen their work. They dressed everyone from Elton John to Mick Jagger, Twiggy to Diana Ross. On the album cover of Abbey Road, three of the four Beatles can be seen wearing Nutters bespoke — John Lennon, Ringo Starr, and Paul McCartney. They didn’t coordinate their outfits that day, they just showed up in the clothes they loved most.

FASHION FOR EVERYONE

The real revolution, however, has been in the development of ready-to-wear, which has overturned the last hundred years of fashion production. Before the 1950s, ready-to-wear garments were the bastard children of absent and ungenerous bespoke fathers. Their cuts were defective, their finishing careless, and as for imagination, they had none. But by the 1970s, this hierarchy collapsed. Technological and organizational improvements made it possible to develop interesting and affordable clothes. This was the real start of the democratization of fashion, when gray flannel suits gave way to denim and sportswear. And with that change, inspiration has flowed in the opposite direction. For centuries, dress norms were largely set at the top and slowly diffused downwards. The lower classes invariably copied or imitated the manners and dress of their betters. But now fashion influence often flows in the other direction. Around the time he showed his safari collection, Yves Saint Laurent declared: “Down with the Ritz; long live the street!”

This revolution in production has had a tremendous impact on clothing prices. Over the last hundred years, the average Western household budget dedicated to apparel has steadily declined. In America, it’s fallen from 14% in 1900 to 12% in 1950. Today, the average American family spends less than 4% of their annual income on clothing (this number would decline to 2% if you excluded StyleForum members or me) – and yet, our wardrobes have never been bigger.

Unsurprisingly, this change hasn’t been uniform across social groups. Lower-income classes – namely blue-collar workers and the unemployed – spend even less of a portion of their income on apparel than the well-to-do. In the 1950s, the average man bought a new suit once every six years; now it happens maybe twice in a lifetime. The same thing has happened with other big ticket items, such as expensive overcoats and leather shoes, which have almost all been replaced by t-shirts, jeans, and sneakers. Just as the dark worsted suit democratized elegance for men – making it possible for them to look dignified without buying ostentatious adornments – cheaper clothes have allowed certain people to look cool without spending a fortune.

And perhaps more importantly, it’s allowed those who are either economically strapped or simply disinterested to opt out of the fashion system entirely, giving them a choice to spend their money on what’s important to them. What fashion declinists see as man’s fall from grace is actually just greater freedom in the marketplace. And what should matter is not what the typical person wears, but the quality and variety of products that are available at various prices.

THE GOLDEN AGE OF FASHION

But what does this mean for the engaged fashion consumer? Ready-to-wear at this time has never been more aesthetically interesting. During the pre-war era, earlier forms of ready-made were little more than watered down imitations of their better custom-tailored counterparts. But in the last seventy-five years, the fashion has exploded with energy and imagination, especially as production has been reorganized to include specialized designers, improved technologies, and global supply chains. Since the 1960s, clothes have become more novel and daring, rather just trying to achieve “class perfection” in craft.

You can see this in how fossilized notions of luxury and class refinement have been overturned by a new value system that privileges ideas over social standing, youthfulness over social respectability, emotional impact over virtuosity. Fashion today draws inspiration from every element of the zeitgeist – films, music, television, sports, art, and so forth. Ruggedness, fantasy, and humor have come into their own as dominant values. Clothes can now be crude, torn, ripped, unstitched, and sloppy, which opens the aesthetic space for how apparel can be both designed and worn. And whereas haute couture houses used to parade their creations in hush-hush ceremonies, fashion shows today are unreal hyper-spectacles that involve light, architecture, staging, music, and podium effects.

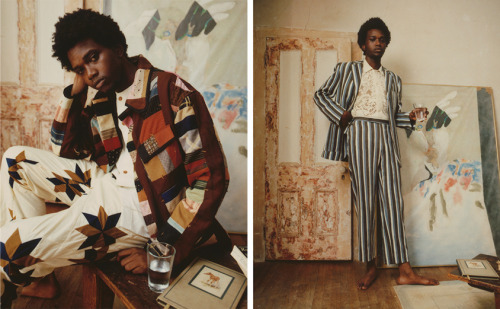

We’ve reached an age where there’s a full kaleidoscope of possibilities in terms of appearance, and the ascendancy of one look doesn’t necessarily displace another. Modern minimalism (Uniqlo) and maximalism (Gucci) are both considered legitimate, as are soft Italian tailoring (Sartoria Formosa) and ironic normcore (Balenciaga), conceptual deconstructionism (Margiela) and rugged workwear (RRL), futuristic techwear (Acronym) and folk clothes (Kapital), the bohemian hippie look (Visvim) and new internationalism (18 East), Japanese avant-garde (Yohji Yamamoto) and prep (Ralph Lauren), vivid colors (Kenzo) and dusty earth tones (Stoffa). You can layer the high and low; wear slim-fitting clothes or wide-fitting garments. As Gilles Lipovetsky writes in The Empire of Fashion: Dressing Modern Democracy: “Nothing is taboo any longer; all styles are accepted and exploited unsystematically. There is no longer a fashion, there are fashions.”

In this way, fashion has become closer to modern art. Whereas both forms were once ruled by strict classical ideas, the space is now free with untrammeled creativity and multidirectional experimentation, where people can both celebrate beauty as well as ideas that challenge traditional notions of beauty.

For some, this fracturing of a social consensus has made the world uglier, but there’s another side of the coin. Greater flexibility in dress, coupled with a vibrant (often online) marketplace, has made it possible to wear almost anything you want. The modern fashion system has every newly invented look plus all the ones that came before it. If you want to, you can dress head-to-toe in 1950s Ivy Style. Rancourt has made-in-USA beefroll penny loafers; Michael Spencer, a sponsor on this site, has unlined oxford button-down shirts; O’Connell’s has saddle shouldered Shetland sweaters; Tailor CAID offers 1950s American styled tailoring; and so forth.

Bruce Boyer recently told me he’s had trouble finding the classic English schoolboy, faux tortoise round eyewear frames of his youth. “You know, the Pantheon or Anglo-American ones in dark or light tortoise,” he says. “There was a time when I could saunter into Trapp on Madison Avenue in Manhattan and they’d have dozens of ‘em at reasonable prices. But you just can’t easily find these sorts of classics anymore. If I wanted frames with plastic shark’s teeth in neon pink it would be child’s play, but to find the old-fashioned, round tortoise ones is all but impossible.”

It’s true that some classics are harder and harder to find. Fran Lebowitz once said in an interview that she had some bespoke eyewear frames made, modeled after a ready-made pair she’s worn most of her life. (She declined to say how much they cost, but she ballparked it around the price of a car). On the other hand, it’s never been easier for an enterprising person to bring a niche good to market – and find customers far flung around the world. Just look at how Mercer & Sons survives on selling baggy button-downs, or the number of projects on Kickstarter. Or even how O’Connell’s has grown by selling heavy English tweeds to trads in Australia.

DRESSING THE BODY

This democratization in fashion has also blurred gender lines. Men are better able to enjoy the creativity that once only women were able to enjoy, while women have greater freedom to wear men’s clothes (e.g. pants, tuxedos, and ties). This rejection of the traditional assignment of clothing to genders goes back to at least the 1960s. Second-wave feminists felt girls were being lured into their subservient roles by first accepting gendered clothing expectations. To be equal to men, they’d would dress like them – or, at least, in ways that weren’t traditionally feminine.

The movement was short lived, at least in its purest form. It peaked somewhere in the late 1960s, with designers such as Pierre Cardin and Paco Rabanne conjuring up streamlined and unisex “Space Age” jumpsuits made from stretchy, synthetic fabrics. But it’s had important reverberations. While Coco Chanel was known for putting women in trousers, and Katharine Hepburn famously dressed in non-binary ways, it’s really been the post-1960s era that has heralded more non-normative clothing.

Think of how Diane Keaton wore androgynous clothes in the 1977 film Annie Hall, or how female punks and grunge musicians thrifted the same lumberjack flannels and combat boots as their male counterparts in the ‘90s. Japanese Rei Kawakubo and Yohji Yamamoto went beyond putting men and women in each other’s clothes, and put them both in clothing that looked neither male nor female. In the Western world, traditional pattern-making emphasizes the idealized, gendered form. For women, that means a curvy hourglass silhouette that follows the body. For men, the broad-shouldered V. Japanese avant-garde designers in the late-20th century, however, played with voluminous fabrics and freer interpretations of the silhouette. The intention is less about sexualizing the female form and more about personal expression. Some of Kawakubo’s dresses even made the wearer look downright alien or disfigured.

Gracia Ventus over at The Rosenrot has a great piece about how Comme des Garcons is ageless, classless, and genderless. “Fashion hinges heavily on sexual connotations because marketers seem to think only sex sells (alongside exclusivity),” she writes. “However, in the world of CdG it goes way off on a different tangent, one that subverts heteronormative standards. Most of the time, one does not wear CdG to appear sexy in the typical sense.”

Alarmists need not be worried – fashion isn’t headed towards androgyny, just more complex and interesting expressions of identity. Today’s clothes are often less about muting gender and more about playing with norms – often in ways that make the wearer’s gender glaringly obvious. Jo B. Paoletti describes this as “sexy androgyny,” clothes that combine both masculine and feminine elements in a way that’s playful, rather than trying to eliminate gender signals entirely. “Part of the appeal of adult unisex fashion was the sexy contrast between the wearer and the clothes, which actually called attention to the male or female body,” she writes in her book Sex and Unisex: Fashion, Feminism, and the Sexual Revolution. No one thinks, for example, that Yves Saint Laurent’s le smoking was anything but a sexier, feminine version of traditional men’s evening wear.

To be sure, some of the concerns expressed by declinists are legitimate. Fast fashion and rapacious consumerism threaten to permanently ruin the environment. Cheap cashmere is turning once-lush East Asian grasslands into arid moonscapes, unleashing some of the worst dust storms in history, as well as a spoiling of the region’s water, soil, and air. The automation of jobs and online shopping threaten to displace millions of brick-and-mortar retail workers. Much of the menswear market is also bifurcating towards the extremes — with uber-expensive luxury labels on one end, and disposable fast fashion on the other. And while we no longer have hard written dress codes, we still have soft dress norms, which continue to regulate people’s behavior. In the best of all worlds, people could genuinely wear whatever they wanted to work – so someone dressed in Rick Owens can work alongside someone in a Brooks Brothers suit – but today’s offices are mostly filled the same vanilla bland, business casual attire that says nothing. To really engage in all that fashion has to offer, you have to be willing to stand out a little.

On balance, however, the fashion world is in a better place today than it was fifty years ago, and certainly much better than the stiff suits fifty years before that (sport coats weren’t even common in American male wardrobes until about the 1920s). The democratization of fashion has been a cumulative thing. First it gave individuals, including the poor, greater freedom in dress (both in terms of personal expression and opting out). The social pressure to conform has also lost much of its force. Just as we accept people of different backgrounds, we’re more accepting today of the variety in appearance. And for the fashion enthusiast, the world is a richer, more interesting place. As Lipovetsky writes, “this pacification of fashion reflects and embodies a growing tolerance, an increased gentleness in mores. Flexibility in fashion, a deep aversion to violence and cruelty, a new sensitivity towards animals, an awareness of the importance of listening to others, a focus on ideas instead of people’s social standing – these are all aspects of the same general process of modern democratic civilization.” Declinists are right in what they see as the changes in fashion, but they’re wrong in how they interpret them. Today is the best time in fashion, and tomorrow will be better still.