Most books on men’s tailoring aren’t very good. Many recycle the same Wikipedia entries, or they do little more than serve as PR mouthpieces for a company. Sometimes they have a few good photos, but they’re the sorts of things you look at once and never remember. Rare is a book like Lance Richardson’s House of Nutter, which is one of the best books on Savile Row I’ve read in years.

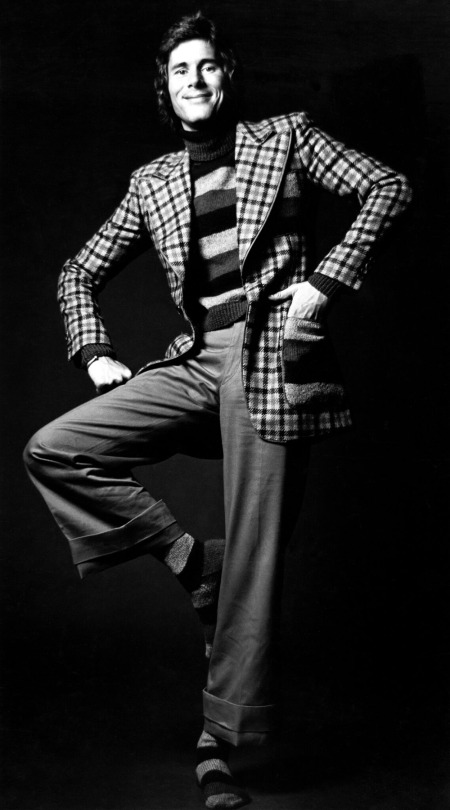

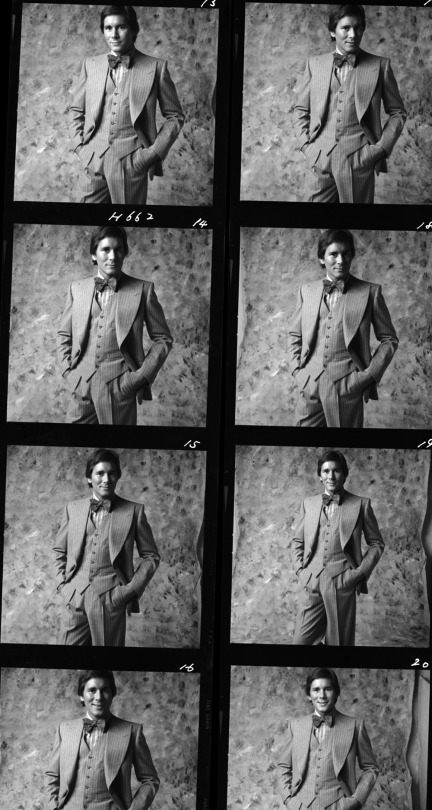

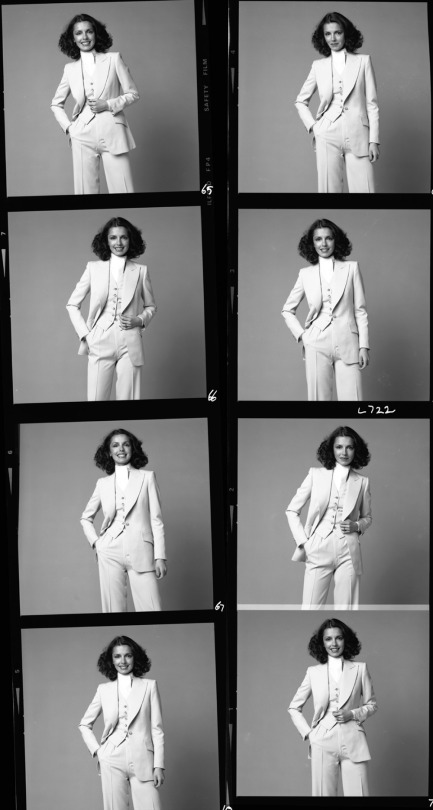

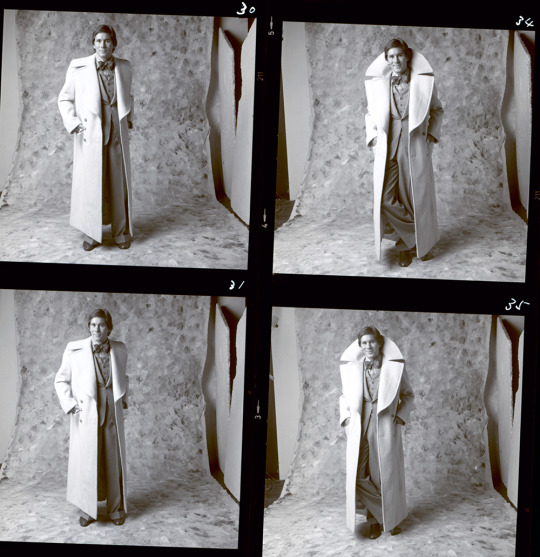

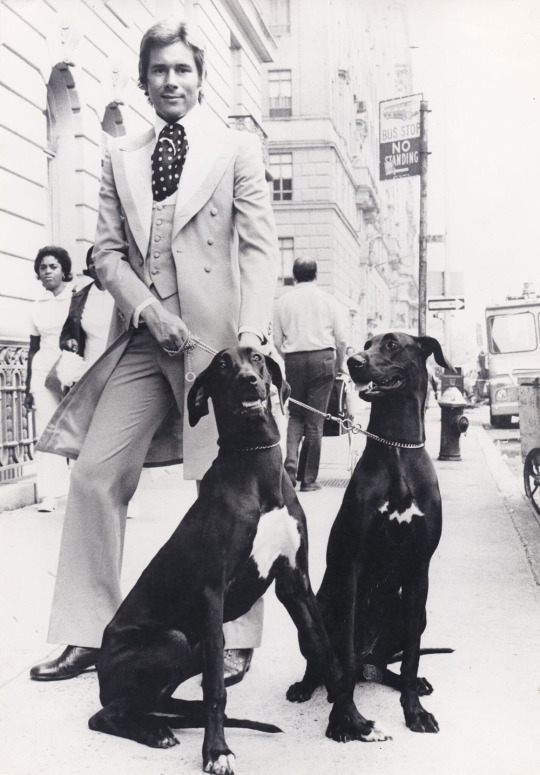

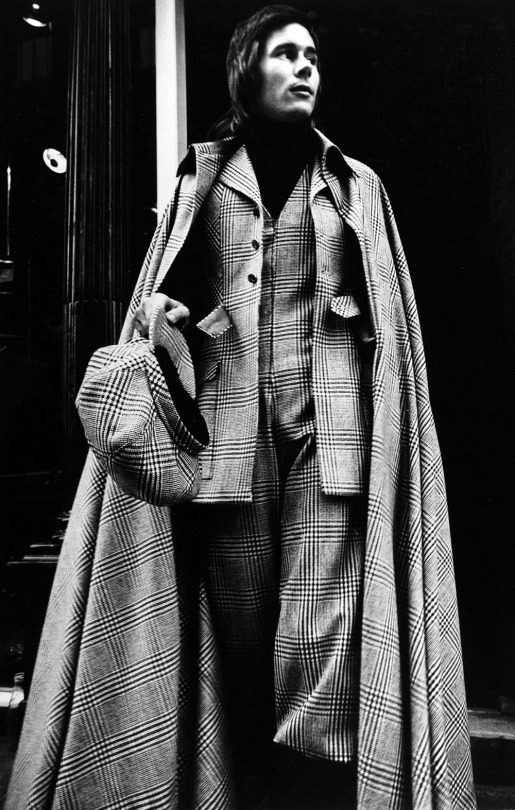

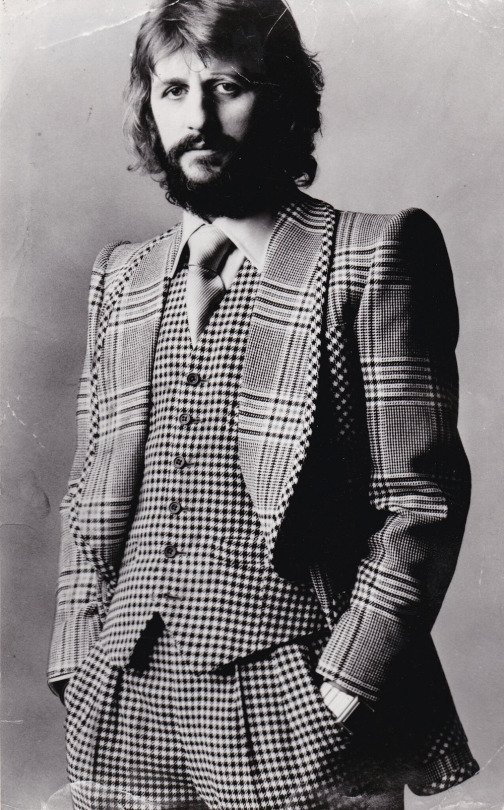

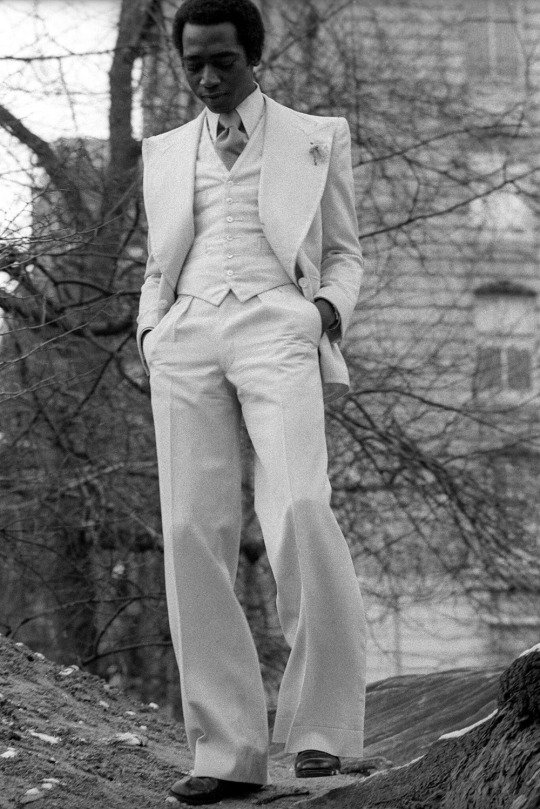

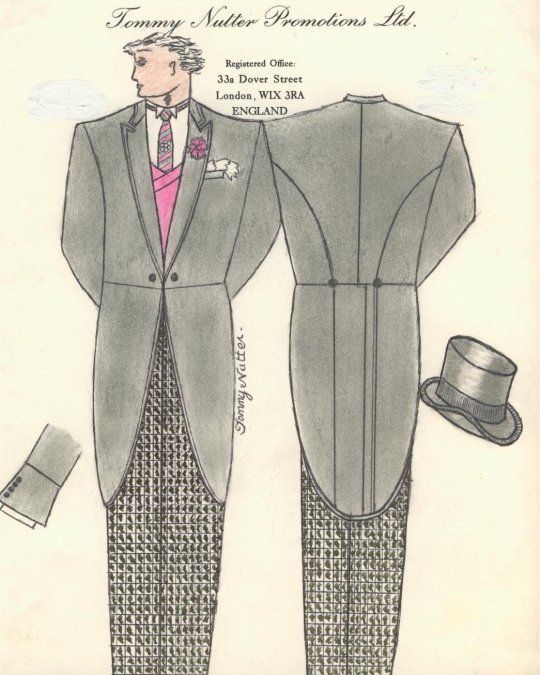

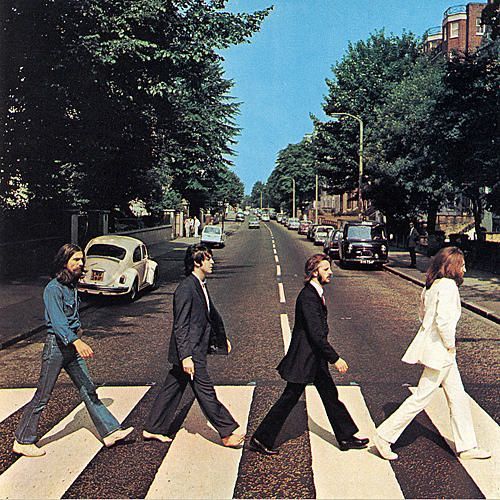

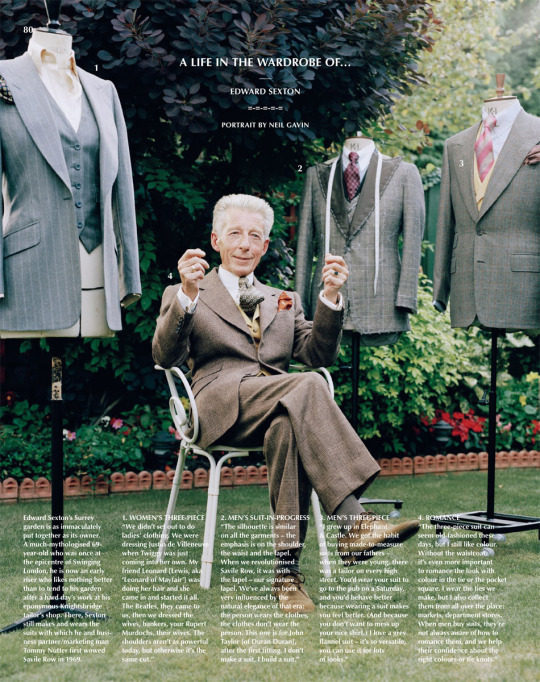

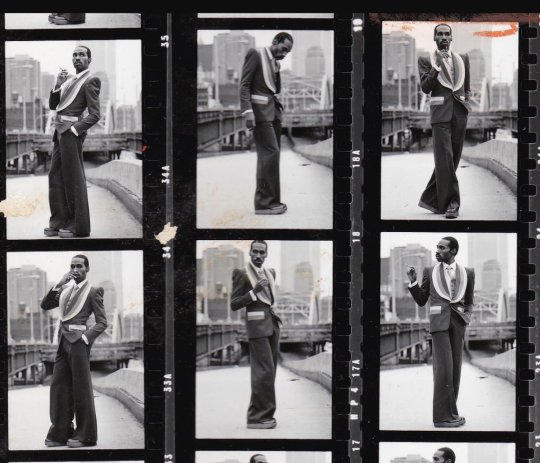

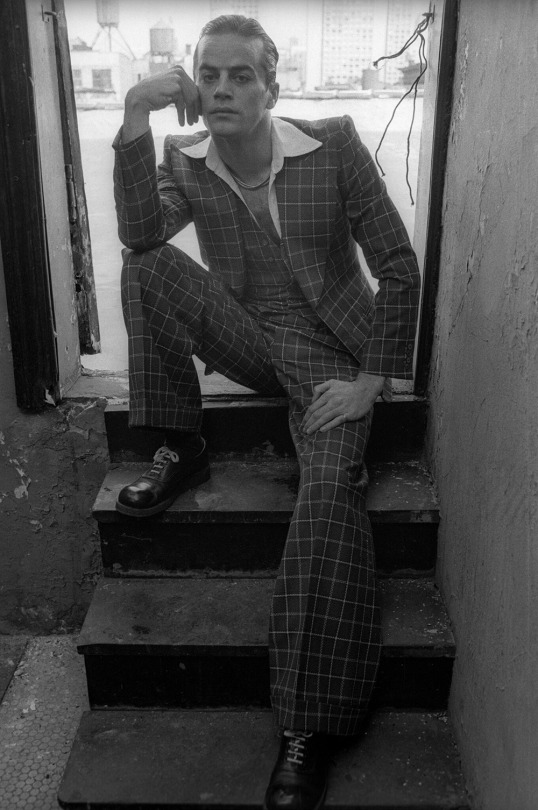

House of Nutter is about the life and times of Tommy Nutter, a Savile Row salesman who created one of the most important tailoring houses in the post-war era. During the ‘60s, most of Savile Row specialized in staid and conservative suits, often following old traditions. Nutter, who originally worked the front of house at Donaldson, Williamson & Ward, wanted something more daring – something bolder. And he was able to turn that dream into a reality through Edward Sexton, the technical genius behind the curtain. Together, they made a look that defined the 1970s. Their house style was full-bodied and long, with a leafy silhouette, strong shoulders, and lapels so enormous, they nearly grazed the sleeveheads. Edges were sometimes taped; patch pockets cut on a bias. Mick Jagger, John Lennon, and Elton John – among many other celebs – wore their bombastic creations, and the tailoring continues to inspire designers today.

Richardson’s book is great because it captures all of the romance of the clothes, as well as the bespoke process, without falling for the naive illusions common among laypeople (or, frankly, most fashion writers). It doesn’t get misty-eyed about bespoke tailoring, but also doesn’t feel cynical or technically sterile. Most of all, Richardson’s book is about the very thing that give clothes life – culture. This is a book about rock ‘n roll, the gay London scene during the 1970s, and even AIDS epidemic (which ultimately took Tommy Nutter’s life). An excerpt from the preface:

Tommy Nutter was obsessed with his public image. He was also gay, coming of age in the oppressive censoriousness of the 1950s. Indeed, his life vividly personified forty years of critical gay history. From underground queer clubs of Soho to the unbridled freedom of New York bathhouses to the terrifying nightmare of AIDS – Tommy was there, both witness and participant. As a gay man myself, it occurred to me that Tommy’s focus on outward appearance might have been a way for him to take control and overcome the more challenging aspects of his lived experience. After all, one way gay men mitigate the perennial pressure to conform to social norms of masculinity is by striving for perfection (in body, in clothes, in career), overcompensating until that which sets us apart – our taste, say – becomes so impressive it assumes its own power.

House of Nutter is full of great stories, often ones involving their more famous clients. For example, here’s one about John Lennon and Yoko Ono:

Accuracy can become collateral damage in the polishing of a good anecdote. “Imagine this,” began a journalist as recently as 2011: “You’re 26, from Barmouth, and a bit of a whiz with a needle and thread. You turn up at work for a day’s tailoring, nervous in the knowledge that John Lennon and Yoko Ono are due in soon for a fitting. However, upon turning the corner to your atelier on London’s prestigious Savile Row you see they’re already there, standing in the window and both stark naked.”

Really? Tommy suggested as much. John and Yoko stripped naked to browse through clothes, he once said: “The customers were complaining, but what could I do? This was John Lennon.”

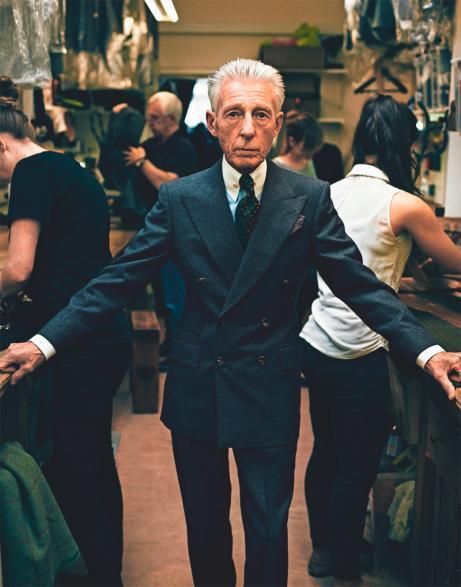

Edward Sexton remembers it slightly differently, with Lady Harlech coming in to pick up her check coat when John Lennon suddenly emerged from the fitting room in his underpants. “Probably got exaggerated slightly,” says Edward. “But everyone is dead and buried now, and I wouldn’t want to contradict Tommy if he said there was nudity.”

Or this little chestnut about how they used to do fittings:

Edward’s input began during the measurement stage. But here, too, Nutters diverged from the standard practice of other Savile Row firms. When Edward worked collaboratively with Tommy, they could be like two lions toying with unsuspecting prey. They were unfailingly proper, of course; every client received impeccable service. But the duo practiced decorum during a consultation or fitting while simultaneously satirizing the pomposity of it all. “Tommy and I used to have terribly funny games we’d play with each other,” Edward recalls. A man with prominent shoulder blades might have them traced out with whimsical loops of chalk. Or Tommy might come in “looking all authoritative,” evaluate the man’s figuration, and then announce to Edward, in a tone of clinical concern, “Crook in the elbows” – a mostly meaningless phrase. “We put on a show for the person and it would be hilarious,” Edward says. “We’d fucking die.”

Some of the stories are less amusing. While the two made for the perfect tailoring duo – Tommy bringing his charm and creativity, Edward his technical skill – they were wildly mismatched in terms of lifestyles and personalities. When they started the firm, Edward was married with a newborn baby, steadfast in his work, and could barely drink more than a few beers without “throwing up all over the place.” Tommy, on the other hand, “was a promiscuous gay man who was chronically incapable of maintaining a relationship or a healthy bank account, and who believed that a few glasses of wine would just ‘loosen you up.’” His vision gave the firm force, and his socializing brought in the right type of clients, but his extravagance also nearly drove the firm into bankruptcy. Tommy was a tormented, creative mind who self-medicated with alcohol, often to the point of blackout. He achieved a level of success few have experienced, but also harbored a dark personal life that’s all too relatable.

In the end, Tommy and Edward had a less than amicable split, which is one of the things that makes the book so remarkable. Edward has always been proud of his work at the company, but the aftermath – Tommy’s attempted suicide and ultimately death from AIDS-related pneumonia – makes this a bit of a sore spot for him. I was surprised to see how much Edward opened up for this book. And how much Lance worked to corroborate stories, tying in the social and cultural history that made Nutters’ work legendary.

I recently talked to Lance about his book and will have a fuller review at Put This On next week. But I couldn’t help but share the photos below – some never seen before online – and excerpts above. Lance’s book is one of the smartest I’ve read in a long time. It’s romantic without being misty-eyed, technical without being staid, accurate without being cynical. It’s also about so much more than clothes, which is what makes it better than most in this field. You can find it on Amazon.

Today, Nutters of Savile Row is long gone as a firm, but its trailblazing legacy can be seen everywhere – from the ‘70s influenced style of Tom Ford to contemporary designer-tailors such as Richard James and Ozwald Boateng, who like Nutters, buck Savile Row conventions. More directly, you can find echoes of the Nutters look at Edward Sexton’s tailoring firm, naturally, as well as Chittleborough & Morgan, two of Sexton’s assistant cutters when they worked at Nutters. Earlier this year, I visited an Edward Sexton trunk show in San Francisco, where I got to try on a Nutter-inspired jacket Sexton made for Richardson after he finished his book. I was surprised by how much I liked it. The style is bold, to be sure, but undeniably chic and tremendously fun to wear. You can read more about Sexton in some of the older posts I’ve written here and at Put This On.

(photos via Lance Richardson, The Rake, and Voxsartoria)