Classic men’s style can be a strange topic at times. While mainstream fashion publications are obsessed with who’s wearing what, this corner of the world is often just interested in clothes. Nothing about the musicians or actors that make a look compelling – celebrity itself is shunned. When culture or history comes up, it’s still often about the clothes themselves. Like how Queen Victoria once visited the HMS Blazer, a frigate in the British Navy, and the ship’s captain dressed the crew in dark blue double-breasted jackets. To make them look a bit smarter, he had the jackets decorated with bright brass buttons. Hence how we get the term blazer.

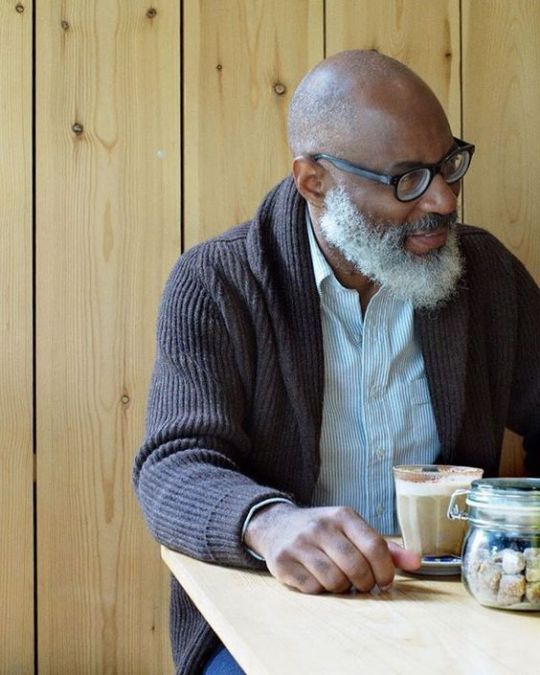

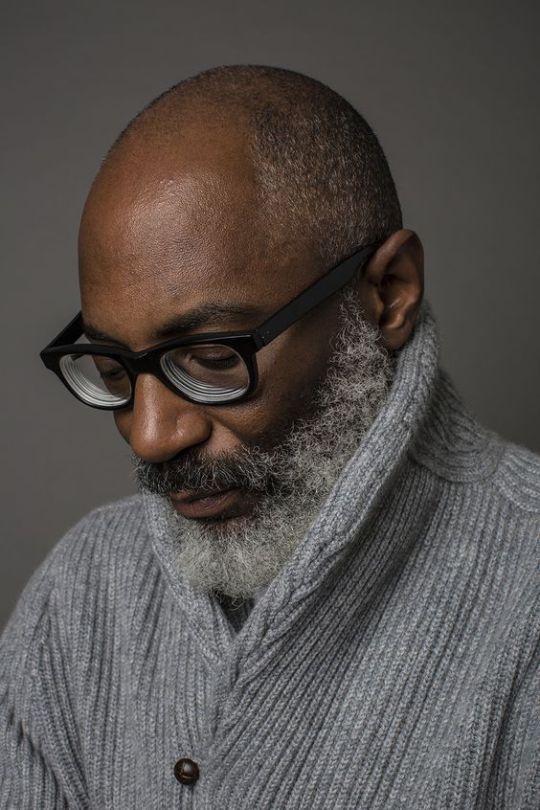

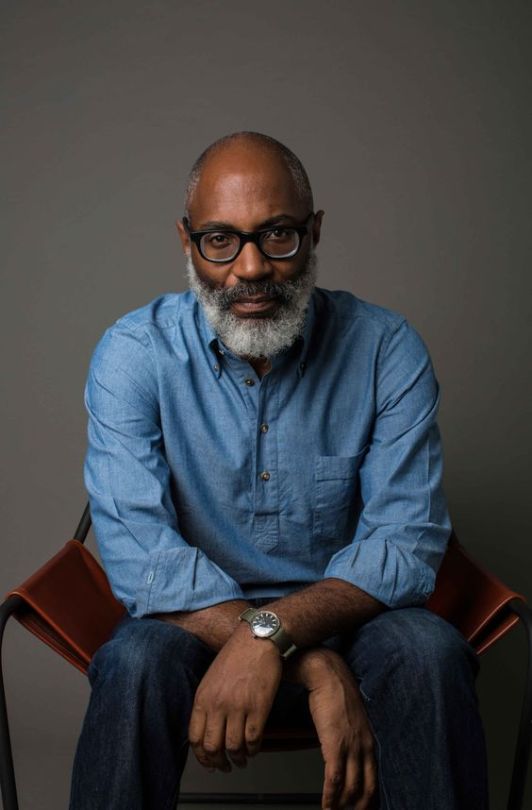

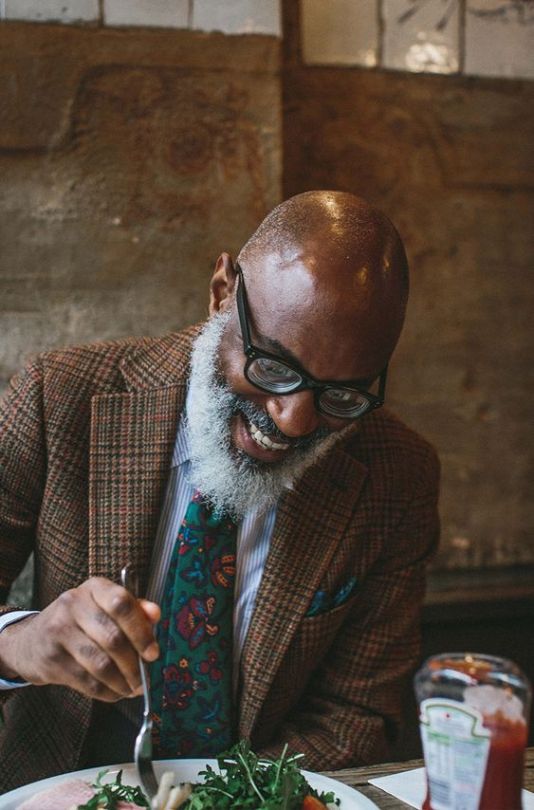

Which is why Jason Jules is such a rare figure. Although he’s clothes mad like the rest of us, I think of him as being more interested in culture than clothes alone. In the late ‘90s, he started his career as a club organizer and promoter, before moving on to be a public relations rep for artists such as Jamiroquai, Des’ree, and King Britt. Later, he wrote for publications such as i-D, Inventory Magazine, and Dazed & Confused, then did brand consulting for Levi’s, A Bathing Ape, and Nike. Readers here will probably recognize him as the face in many of Drake’s lookbooks (he also once walked the runway for Paul Smith). While Jason can talk about clothes, he’s more likely to make the connection between the things we wear and contemporary influences.

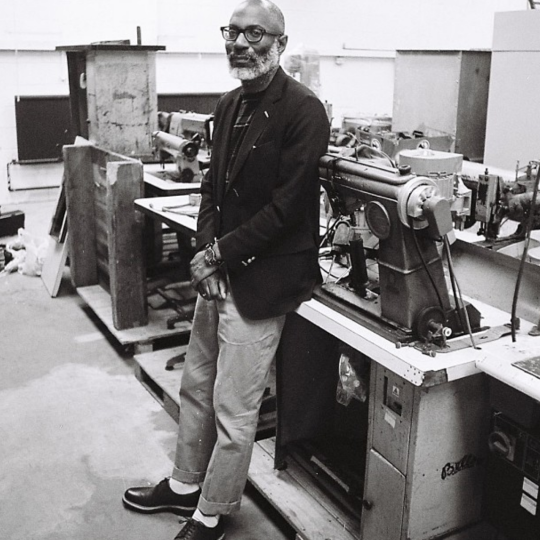

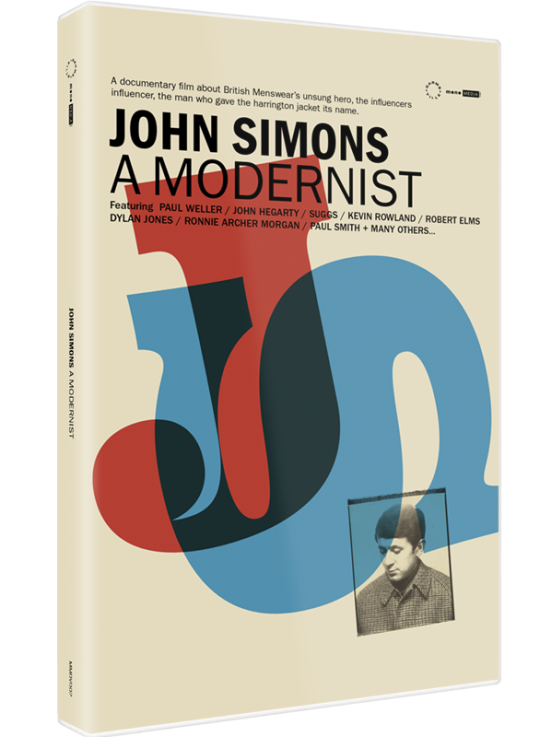

Later this month, he’s also debuting his film, A Modernist. It’s an hour-long feature on the legendary London clothier John Simons, sometimes referred to as the patron saint of English Ivy. John Simons is one of those rare retailers that serves as a cultural gateway for many people – if the shop carries it, it’s considered good. Since the ‘50s, they’ve specialized in things such as button-down collars and Baracuta Harringtons, which they’ve sold to everyone from businessmen to mods to skinheads (the non-racist kind). A Modernist is not just about the shop and its clothes, but also the cultural attendants that came with them.

“When it comes to Ivy style, jazz, and modernism in general, John was Wikipedia before Wikipedia,” says Jason. “He has a deep understanding of clothing and loves sharing it with people, regardless of their background. That’s why there was such diversity among the shop’s customers. He sold to kids who were into reggae and ska, just as he sold to advertising executives. He treated everyone equally.”

The clothes were distinctively American, but much like how Ivy Style was transformed in Japan, they took on new meaning in Britain. Mods, skinheads, and suedeheads wore them not because they wanted to imitate American students across the Atlantic, but rather because “their mates were doing it.”

I think the clothes meant different things to different people. I imagine skinheads and suedeheads were reacting against the hippie movement at the time. There was a sort of neatness about the look that appealed to their working class roots, but the clothes also embodied a certain aspirational element. It was looking a bit more accomplished than what your wage packet might suggest. The mods, on the other hand, had good jobs and they liked dressing a certain way. But the appeal was often still a bit aspirational – looking a bit outward at the time, especially since Britain was just coming out of the war.

I’ll have a full interview with Jason next week at Put This On, where we talk about his film and views on various topics. But while we chatted, one of the things that struck me was how these same clothes – styled in the way they are at John Simon’s shop and worn by Brits abroad – don’t have the same kind of baggage they do in the US. Fifteen years ago, prep was ascendent with brands such as Ralph Lauren Rugby, Band of Outsiders, and Brooks Brothers Black Fleece. Today, those brands have all shuttered; J. Crew is struggling to find its footing; and Ralph Lauren is accused of being out-of-touch. Traditional American clothes simply don’t have the same appeal.

Part of that is about the natural lifecycle of trends, as even classics have their time in the limelight. The other part is about how it’s become harder to ignore some of Ivy Style’s uglier associations, particularly in today’s highly charged political environment. One of the original appeals of prep was that things were better in the past, and people could turn to timeworn traditions in order to build better, more dependable wardrobes. Today, nostalgia feels a bit outmoded and people are careful about how they romanticize history. The things that made prep cool – the look of 1950s boarding schools, elite colleges, and Wall Street – were also the same places that discriminated against minorities and women around the same period (and, at times, continue to). Pete wrote a great essay about this a few years ago at Put This On:

Everyone likes to stunt sometimes, but prep stunts in ways that seem dated. Prep implies privilege and inherited money; some of prep’s charm comes from the unquestioning self-confidence bestowed only by independent wealth. Americans have always had a weird relationship with being born into something versus earning it. We like to poke fun at the rich, but not too hard, because of course someday that’ll be us. Today we still like our wealth obnoxious. But not smug or entitled.

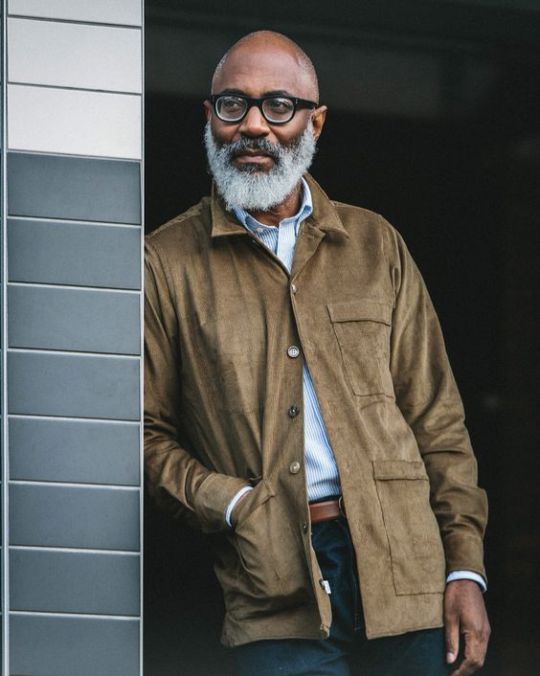

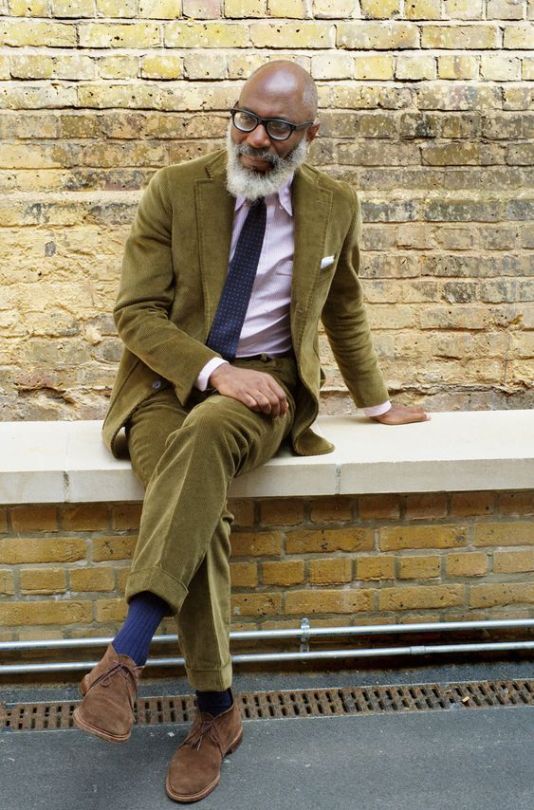

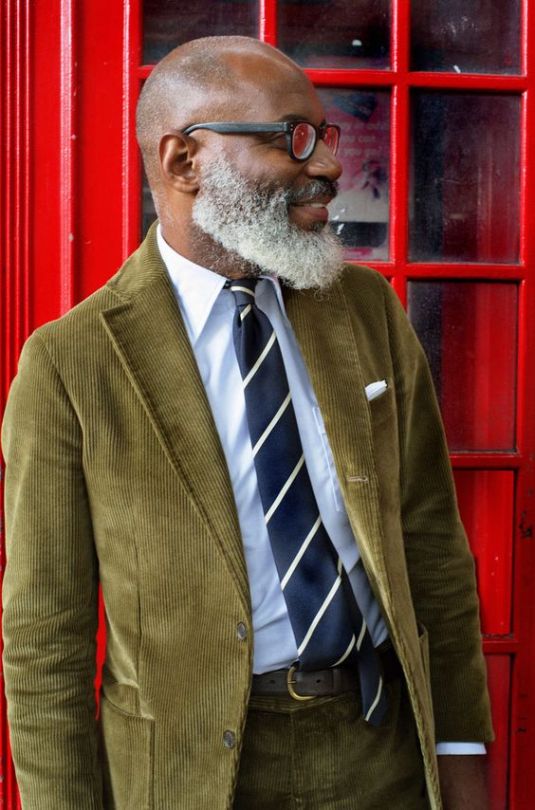

In Britain, however, the clothes feel like they take on new meaning, free from such baggage by virtue of their geographical and cultural distance. There’s still an element of wealth and privilege – otherwise, this wouldn’t be aspirational – but it’s easier to ignore the uglier, more polarizing elements. A Harrington jacket teamed with a button-down, a pair of suede chukkas, and some five-pocket Bedford cords suddenly feels like a different thing. It’s more modernist; less elitist.

“I was asked a few years ago how long I’ve been into Ivy,” Jason laughs. “I hadn’t even realized I was into Ivy. I was into button-down shirts and loafers and flat-front trousers. I was into patch pockets. I was into The Graduate and Steve McQueen. I was into Blue Note Records and jazz. I liked a certain look, but for me, it had a different meaning. Wearing such clothes, I felt I like I was in the process of subverting something, even if it’s only what it means to be a black kid in East London.”

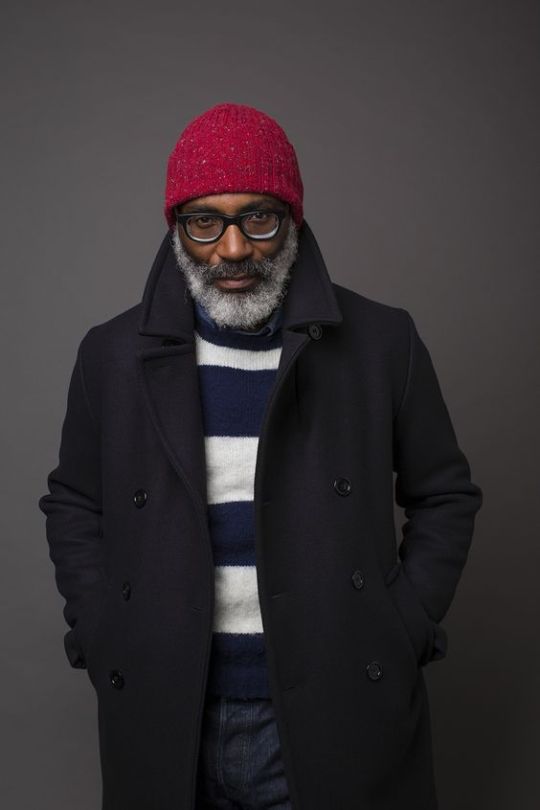

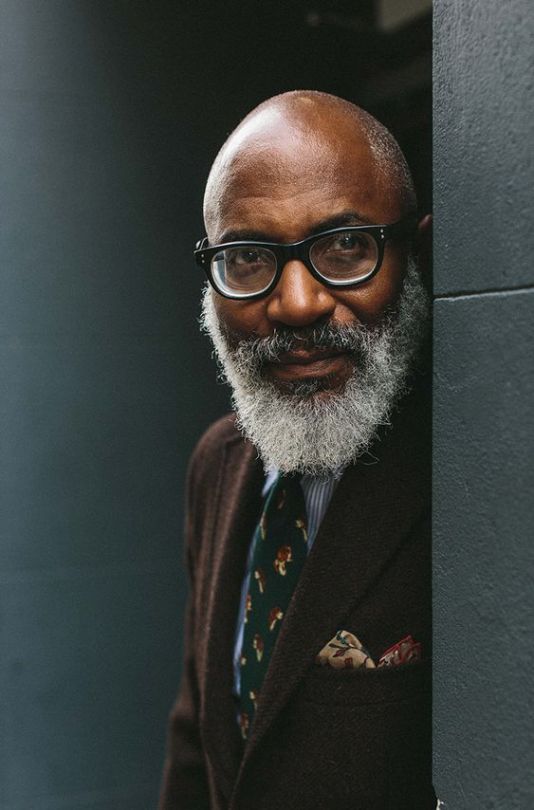

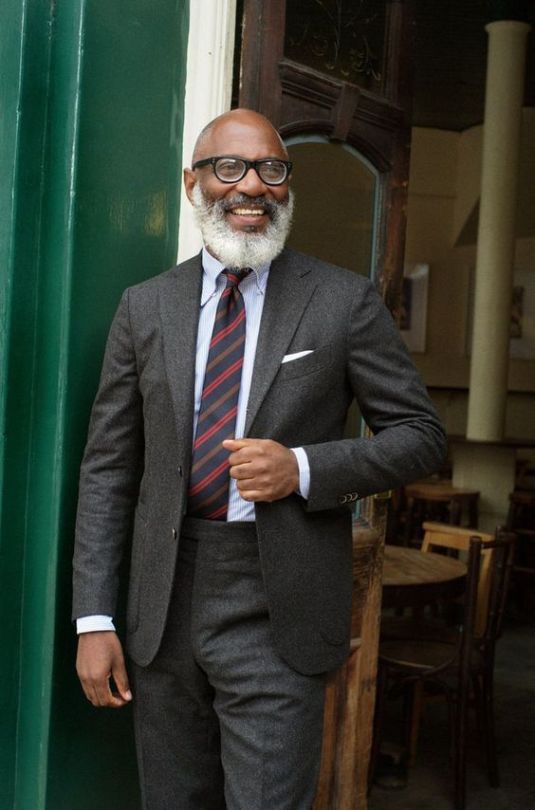

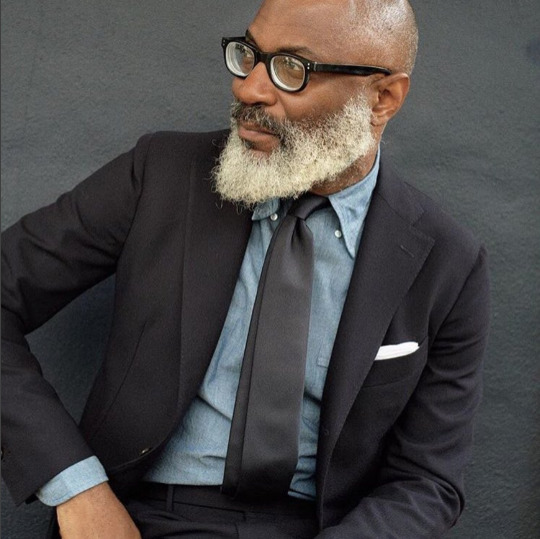

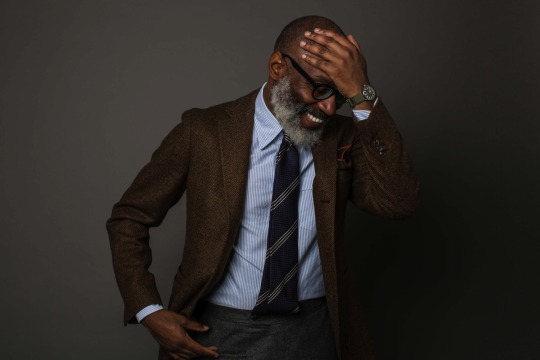

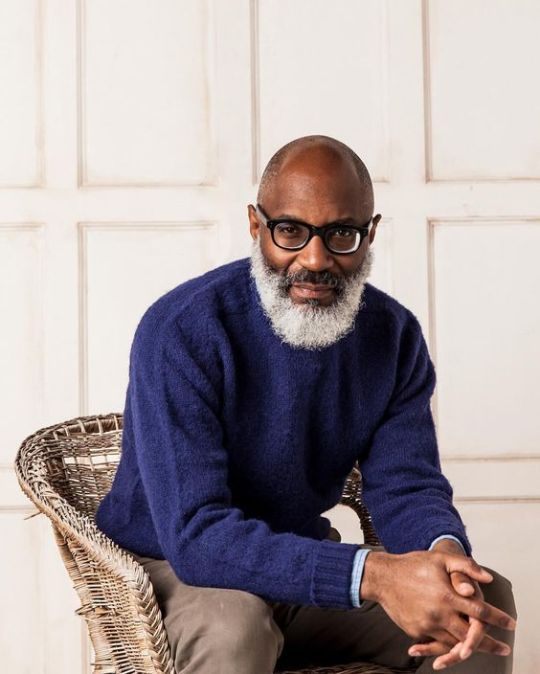

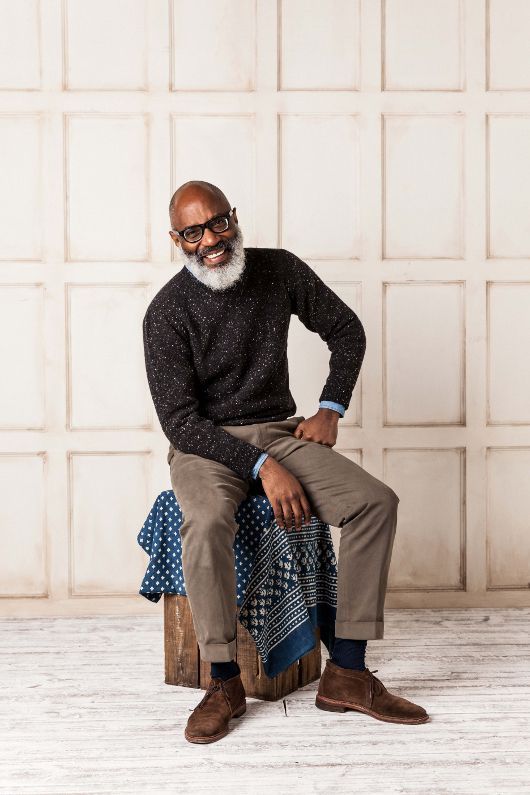

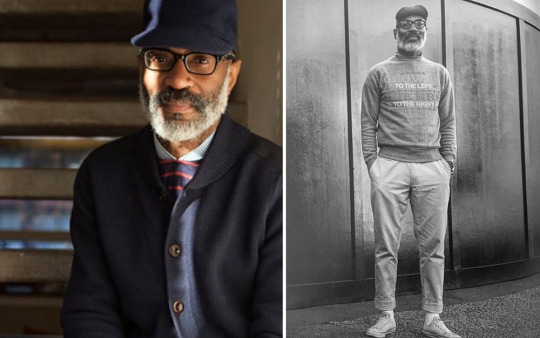

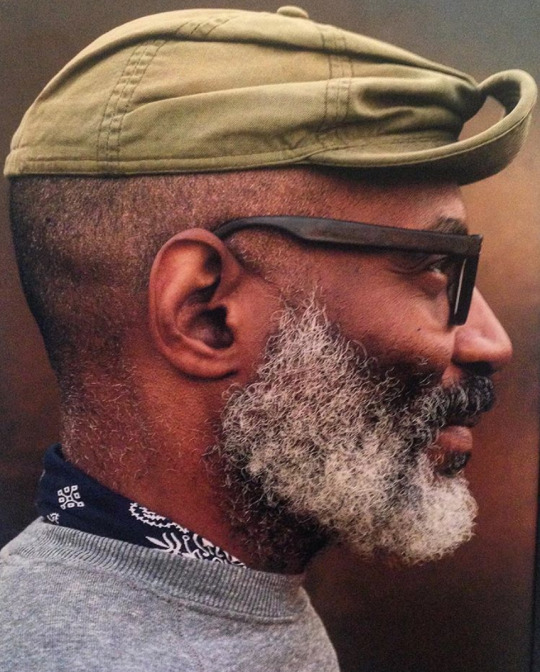

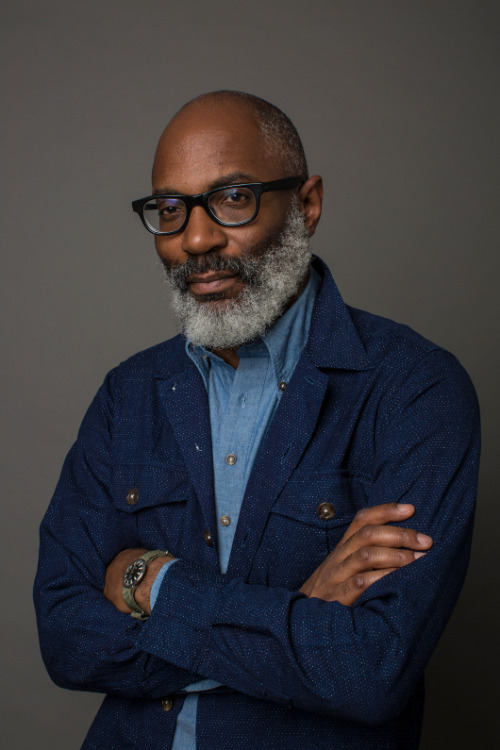

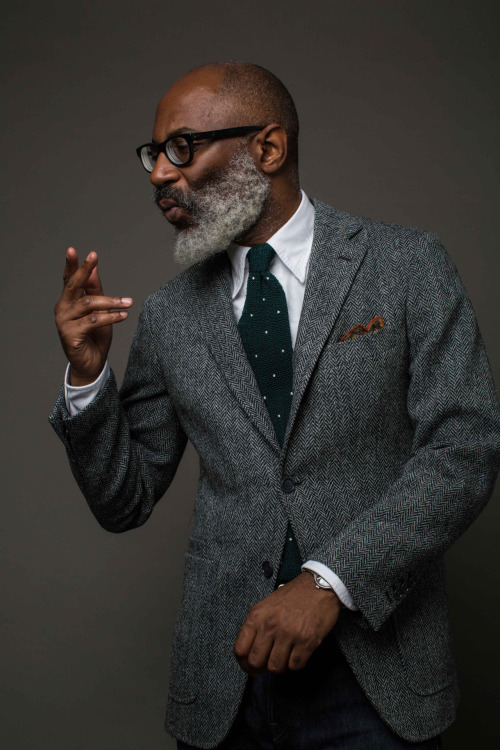

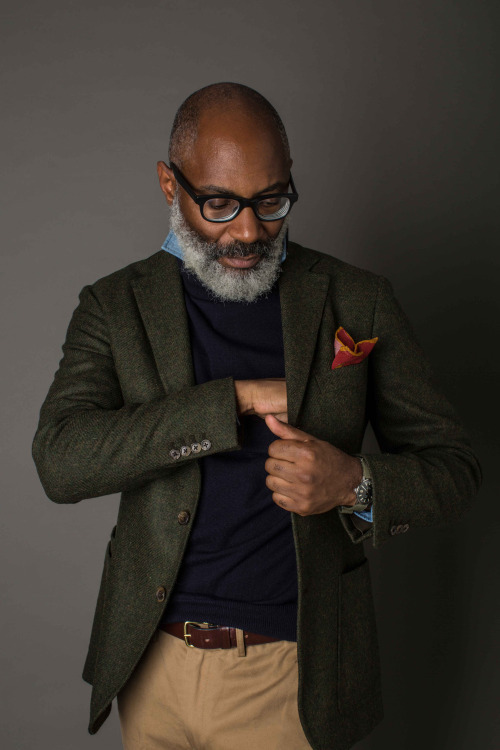

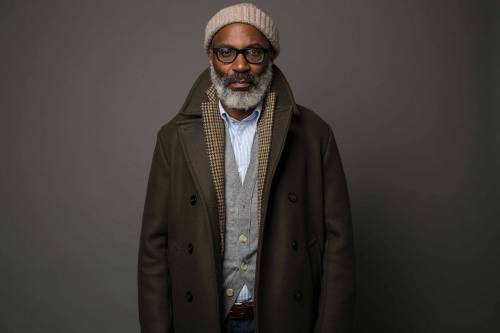

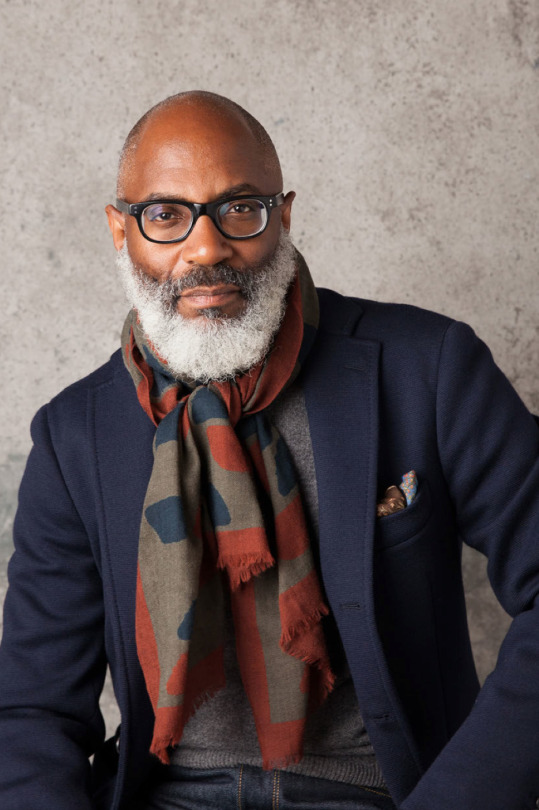

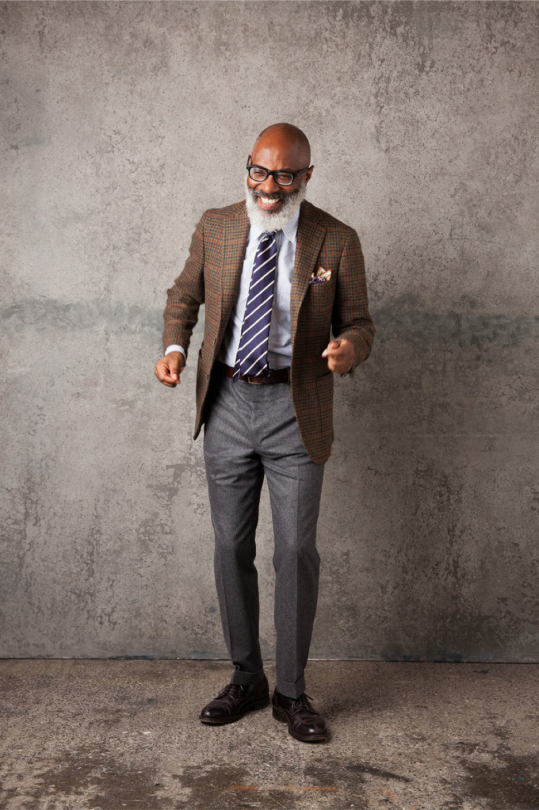

Anyway, this post isn’t supposed to be about the film, that’s coming next week at Put This On. It’s supposed to be about Jason’s personal sense of style. Like many of the better-dressed men I know, Jason didn’t have much to share in terms of universal rules. When pressed to even describe his own sense of dress, he joked: “if you ask the friends I went to school with, they’d describe it as boring.”

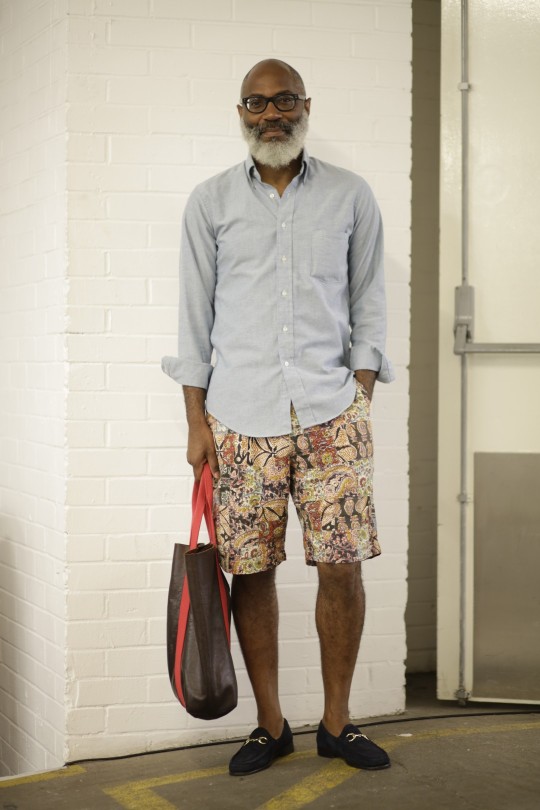

Scrolling through old photos of him, however, you’ll find he’s always dressed the same. He likes straightforward brands known for “doing one thing well.” So, Pendleton shirts, Levi’s jeans, Red Wing boots, Dickies work pants, Drake’s ties, Brooks Brothers button-downs, Schott leather jackets, Converse Chuck Taylors, and so on. Then there are brands that reinterpret those classics, such as Engineered Garments and Norse Projects on one end, and Uniqlo on the other.

Where Jason’s style comes into its own is in how he puts things together. He likes having a bit of tension somewhere (“I don’t like looking too correct”). That means chinos that are a touch wide, rather than perfectly cut. Or pants that are either too long or too short. “A classic white t-shirt is a classic white t-shirt; a pair of Levi’s is a pair of Levi’s,” he says. “I interviewed Shawn Stussy once and we talked a lot about Brooks Brothers. He said they were a big influence on the clothes he designed. The proportions and sizing are always different – more street, more baggy, more casual – but many guys have taken what are essentially classic American clothes and turned them into something that reflects their own lifestyle. That’s the goal.”

For readers interested in learning about the film, I’ll have a Q&A with Jason up next week at Put This On. The film itself will be available on DVD at Mono Media starting April 23rd. Jason is also working on a book about sneakers. “It’s not going to be about someone’s huge collection and the sneakers they missed out on a teen. It’s more about where sneaker culture is going and how it impacts the rest of culture – social media, identity, luxury, consumerism.” The book is slated for release sometime next year. Those interested in keeping up with Jason can find him on Instagram.