There are two often-recited stories for how tweed got its name. The first is that it was originally a misreading of tweel – an old Scottish word for twill – which was supposedly written on an invoice somewhere. How that misreading eventually made it into the more general vernacular, nobody knows, but it’s probably the pithiness of the story that counts. The other guess is that the word tweed refers to how the cloth originally came from the valley of the River Tweed. That, to me, seems like the more likely reason. Many of the ancient names we have for fabrics are derived from the places where the material was often made – cashmere for Kashmir (India), muslin for Mosul (Iraq), worsted for Worstead (England), cambric for Cambrai (France), and the endlessly cited denim for de Nimes (also France). In many ways, the names we have for fabrics today tell a story about earlier waves of globalization.

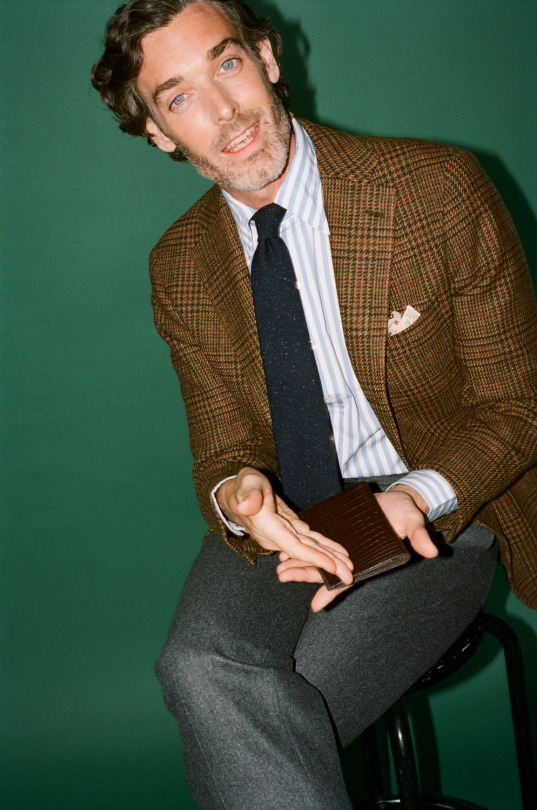

For all the histories we have about tweed, however, few people really know what defines the cloth. It’s one of those “you know it, when you see it” type materials. Prickly in texture and earthy in color, it’s the fabric of fall and winter. It somehow manages to be one of the least and most comfortable materials you can wear. Least in the sense that it’s often too scratchy and rough to be worn against bare skin, which is why it feels and looks better when layered over thicker dress shirts – oxford cloth button downs or brushed cotton flannels. Tweed trousers, if you have occasion to wear them, often need to be fully lined. At the same time, tweed has an undeniably comforting quality to it. It’s hardy and reliable; sturdy and flattering. In a genuinely classic cut, a tweed jacket is something you can wear for the rest of your life.

The best definition of tweed is a kind of negative definition – a way to understand to cloth by what it is not, rather than what it is. Tweed is one of the oldest, if not the oldest, of British textiles. Before the advent of modern loom technology, European fabrics were stiff and heavy. City fabrics (such as those that would be worn in London) were naturally more refined than country cloths, but they were still more substantial than the Super 100s you’ll find in stores today. Scottish fabrics were rougher still. After the union of the two kingdoms, an economic board was set up to organize and encourage the cottage industries around Scotland. Among those were tweed weavers, who for centuries, made workwear fabrics designed for heavy use out on the countryside.

In the old days, Scottish tweeds were woven from local and native wools, often Cheviots that were spun into woolen yarns – which is to say they were carded, not combed. Most of them were designed for men, in dark and dull colors such as black and brown, although women wore the material as well. As technologies improved and international trade increased, Britain started importing German textiles, which were softer and more refined. In old, mid-19th century clothing catalogs, you’ll find clothes described as being made from “German Lamb” and “German Fleece,” which is to say they were constructed from superfine Silesian and Saxony merinos (what today would be called English “Botanies”). And yet, even against the possibility of this superior comfort, Scottish tweeds persisted for the same reasons they do today.

When shopping around, you’ll find an endless number of tweeds. Some are described by the type of sheep that provided the wool (e.g. a Shetland or Cheviot tweed, which are named after Shetland and Cheviot sheep). Then there are regional tweeds, such as Harris and Donegal, both woven in the Harris and Donegal areas, respectively. Donegal is defined by its flecked coloring, but I find Harris can take any number of forms. And finally, there are sporting, game, and thornproof tweeds, which are often tougher and more densely woven than the spongy stuff, such as what you may get from Lovat Mill.

Pattern is tweed’s other important dimension. You can find solid or semi-solid colorings, but many of the best designs come in familial and regional checks. Tartan tweeds, which are rare, used to signal a belonging to a certain clan or family. Regional plaids, what are sometimes called district checks, were once connected to sporting estates. Back in the day, the owners of Scottish Highland estates used to clothe their ghillies, foresters, and keepers in fabrics specific to their plot of land. And, interestingly, many of those patterns have become more generally used in men’s tailoring. For example, glen plaid – that simple, crisscross check – is now seen on business suits, but it was once a more casual, country pattern. The word “glen,” after all, is Gaelic for valley. Hence terms such as Glenurquhart check for the Glen Urquhart estate, and Glenfeshie for the Feshie estate.

If the prickliness of tweed is too much for you, find a worsted or cashmere-blend fabric with a traditional tweed pattern (what’s colloquially referred to online as a faux tweed). Harrison’s Glorious Twelfth and HFW’s Worsted Alsport are good starting places if you use a bespoke tailor, but you can find such things in ready-to-wear as well. Either way, a couple of good tweeds can be great for almost any wardrobe. Next to a dark suit and navy sport coat, I can’t think of anything more useful. Wear a tweed jacket with tailored trousers in wool flannel, cavalry twill, whipcord, moleskin, or corduroy. It can also be dressed down with jeans and a sweater. Earthy browns, mossy greens, and dark blues will often be your most versatile colors, although a grey herringbone or Donegal can be a wonderful thing. If you get something made from a more loosely woven cloth, consider flapped pockets instead of patched. Those are less likely to bag out over time.