A few years ago, British writer Alain de Botton penned an essay on why we hate cheap things. His point was simple: we don’t think we’re snobs, but we often behave like we are. We conflate worth with price and assume cheap things can’t be any good – after all, there must be a reason why they’re cheap. And in doing so, we miss many of the more common pleasures surrounding us.

His essay starts with the story of the pineapple. Once a rare and exotic fruit, pineapples were difficult to cultivate and even more difficult to transport. In the 17th century, a single pineapple would cost about $7,500 in today’s dollars. Only royalty could afford to eat it. Russia’s Catherine the Great was a big fan, as was Charles II of England. Grand monuments and buildings were erected in its honor; poems were written about its flavor. If you were so lucky to get a pineapple, you’d put it on your mantle until it rotted and fell apart. Pineapples were a luxury, even a status symbol.

Then, at the end of the 19th century, two things happened. First, large commercial plantations were set up closer to the West, such as in Hawaii. Second, the advent of steam ship technology dramatically lowered transportation costs. Today, you can get a pineapple for less than $5 in almost any supermarket, sometimes available in bite-sized pieces contained in see-through boxes. There’s no glamour to pineapples anymore, but it’s not because the fruit has changed – only our attitude towards it.

Botton’s essay, which has been recently repackaged and sold as part of a book, explores the question of why. Why do we hate cheap things? His answer is a bit crude and relies on a somewhat simplistic presentation of pre-industrial production and evolutionary psychology. But I think he has one important point: the relationship between price and quality today is looser than it once was. People assume that cheap things won’t last, but the industrial revolution has made it possible to buy all sorts of affordable things that will last forever and function reasonably well for years. And yet, the idea persists that cheap things can’t be good.

There’s a ton of literature on this in behavioral sciences. The price of wine, for example, can affect people’s perception of how something tastes. In blind taste tests, non-experts will often show a preference for cheaper wines. But in similar groups, when the price of a wine is revealed, they’ll show a preference for the more expensive bottles. In other words, non-wine-experts like cheaper wines until they know it’s cheap – then they’ll prefer whichever bottle is more expensive. Vox Media has a nice video about this, which I’ve embedded above.

The are similar studies on country-of-origin labels – not the same as price, but closely related. The most famous (or at least the most cited) study was done in 1965 by Robert Schooler. He took a group of 200 students and had them evaluate a set of identical fabric swatches – all plain weaves, beige, and made of 80% cotton and 20% linen. The only difference is that each swatch was labeled with a different country-of-origin label. One was said to be made in Guatemala, another in Mexico, another in El Salvador, another in Costa Rica, and so forth. And, as you can probably guess, students saw differences in quality that weren’t there, often colored by their own biases about those countries.

This isn’t to say that quality doesn’t correlate with price. For clothes, there’s often a bare minimum for how much something has to cost if you want to use good materials and skilled labor. It’s hard to get a pair of Goodyear-welted shoes for less than $150. Densely knitted cashmere sweaters will likely run you north of $400. And you can’t find a great suit nowadays for less than $500 – they just don’t exist.

At the same time, people’s perception of quality is more often colored by their hate of cheap things than we’d like to think. Hell hath no fury like a man who just found a small scuff on his Allen Edmonds factory seconds. Nevermind that, should they have passed his quality control test, the shoes would be summarily dragged across hard concrete for the next decade or so. Or see how the initial stiffness in Meermin’s shoes is treated compared to Saint Crispin’s – both brands known for their stiff constructions, but only one has a thread on StyleForum with complaints. I can’t help but think people’s perception of “goodness” is often heavily colored by an item’s price.

A few years ago, I interviewed Jeffery Diduch, one of the more level-headed people I know in the fashion trade, and the VP of Technical Design at Hickey Freeman. We talked about why it’s hard for everyday people to discern quality. Commonly cited benchmarks – such as Super 100s wools and handsewn seams – aren’t as reliable as people think. And the things that do actually determine quality, such as a yarn’s fibers or a garment’s internal construction, aren’t things consumers can easily see. Instead of conceptualizing quality as a linear thing, with one object being clearly better than the other, Diduch suggests that making clothes is more like making food. You can hire the best chefs in the world and buy the most expensive ingredients, but if you want to sell something, you need to make sacrifices. Perhaps you hire skilled, but less renowned, chefs. Maybe you use slightly lower-grade olive oil, but decide that the truffle oil must be kept if the dish is to have its signature flavor. This is very much like what designers do. There are hundreds of steps that go into making a garment, and each designer has to decide which steps are most important to him or her. These kinds of calls are going to be very subjective – and technical in ways non-experts won’t understand.

Instead of getting caught up in quality, price, and county-of-origin labels, I think people would be better off if they just developed their eye for how something looks. There are certainly some cheaply made clothes out there that will fall apart or look worse with wear. Fast fashion brands such H&M are probably best avoided, and you should probably know the bare basics of quality (avoid shoes with corrected grain leather, for example).

That said, to the degree that quality matters, it should manifest itself in how a garment feels and looks. And if you have an eye for style, you can ignore these more irrelevant dimensions on quality entirely. One of my favorite field jackets is from Polo Ralph Lauren – it fits me better than many of the “higher end” brands, has better detailing than things I’ve seen from Japan, and is simply a good, honed-in version of something Ralph Lauren has been making for decades. Instead of obsessing over price and quality, the two dimensions that dominate online clothing forums, I think you can find great stuff by following these more general rules:

- Develop an Eye: As mentioned above, to the degree quality matters, it should be apparent when you put something on. Does the item make you look and feel good? Does it fit well? Is the silhouette flattering and stylish? Often times, I think people would be better off if they thought harder about design and aesthetics, and less about price and manufacturing specifications. You’re buying fashion items, not computer equipment. Focusing too much on quality risks conflating expensive items with stylish items. The two are not always one and the same.

- Find Trustworthy Companies: People have never been more cynical of brands, but truthfully, I think consumers are often better off finding trustworthy companies than trying to play expert themselves. Find brands and stores whose reputation ride on their carrying worthwhile products. Often times, I find that’s truer of smaller, specialized boutiques than well-known luxury labels (Dana Thomas wrote a good book years ago on how luxury lost its luster). Find brands you can trust and go off direct experiences with previous purchases. If you like a pair of jeans you bought at Self Edge, the next pair will probably be pretty good too.

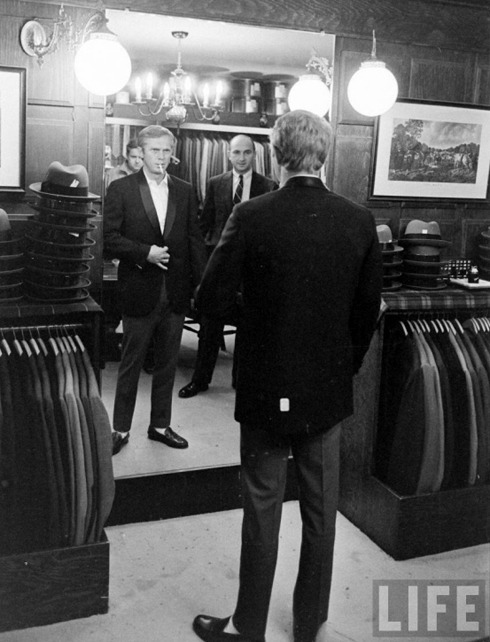

- Broaden Your Experiences: For the two things above, you only know when something is good when you’ve compared it to other things. Broaden your experiences. Go to a bunch of stores, maybe some just outside of your price range, and try things on. Maybe you’ll develop a new appreciation for how something can look. Additionally, broaden your horizon when it comes to fashion. There’s a ton of inspiration to be had everywhere – music subcultures, niche films, and historical movements. You don’t have to delve into cosplay, but a little familiarity with the sleaziness of the 1970s goes a long way in wearing a Tom Ford suit well.

- Beware of Trends: I’m not the kind of guy that believes everything needs to be a classic, but nowadays, when you’re buying clothes, the design is more likely to give out than the construction. If something is red hot one year, there’s a chance you’ll get tired of it once everyone has the same thing. That, in the end, is the real problem with fast fashion – if the item is being sold at Zara, the style is likely at the end of its fashion lifecycle. It can be fun to participate in trends, and I certainly do, but beware of things you might hate in six months.