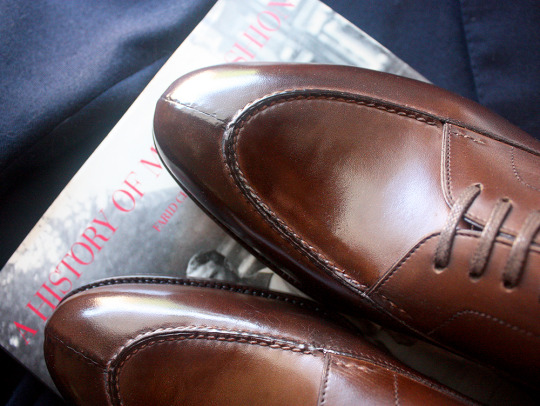

These cat-monogrammed split-toes may be the best and most ridiculous thing I’ve ever bought. They’re from Saint Crispin’s, which has become one of my go-to companies for dress shoes. For years, I’ve always considered Edward Green to be my favorite label for footwear. Like Drake’s, their batting average in terms of design is exceptional, which means you can pick almost anything from their catalog and be assured you’ll look great. Getting a good pair of shoes from Saint Crispin’s, on the other hand, takes a bit more deliberation, but you can also wind up with something more unique.

I think of Saint Crispin’s as the bridge to bespoke – sitting halfway between ready-to-wear and something truly custom. A lot of it is about the shaping. Since Saint Crispin’s are handwelted at the front and pegged at the waist, they don’t have the welt you traditionally find on Goodyear welted footwear, which allows their shoemakers to cut the soles closer to the uppers. Coupled with their sleek, foot-hugging lasts, this gives their shoes a kind of shapeliness you don’t see everywhere else. See this post for a comparison of how Saint Crispin’s chukkas compare to a similar pair from Crockett & Jones. The difference is incredible.

Since every pair is made-upon-order, you can also ask for almost anything you want. That includes the design, which for bespoke firms such as G.J. Cleverley, I find to be half the draw. I recently bought these two split-toes from Skoaktiebolaget (an advertiser here, but also one of my favorite shoe shops because of their great service). I had them modify Saint Crispin’s traditional split-toes with the sort of v-shaped wing you see on the side, going from the apron to the quarters. And as a tribute to my cat, instead of the personalized monogram they normally peg into their waist with brass nails, I had them do an outline of a feline. I can’t take credit for the idea; this customer did it first.

I also love how Saint Crispin’s handsewn aprons show up on suede. With Edward Green, the company’s signature pie-crust aprons almost disappear on napped leather. That’s because the fiber structure on suede is less densely packed, so it’s hard to get that kind of fine detailing. Saint Crispin’s, on the other hand, uses a butted seam, which means the handwork looks just as good on smooth calf as it does on napped leather.

The company has its drawbacks. For one, as I’ve mentioned before, since their lasts are so shapely, it can be hard to get the right fit. These don’t fit like your roomy Aldens – just a millimeter off and it’ll take weeks before you can stand walking in them for more than a few hours. One clever solution: the company allows you to modify their lasts by either adding cork to their standard wooden forms or shaving off material. You can also get a pair trial shoes made from your customized lasts (mine, made from tan scrap leather, are pictured below). They’re too roughly made to be worn as regular shoes, but they give you a good idea of how your new last feels.

Frankly, the process isn’t too different from how many bespoke shoemakers make their lasts these days, where they’ll buy standard Springline forms and modify them with rasps and cork. The one difference: where a good bespoke shoemaker should guarantee you a good fit, Saint Crispin’s can take a bit of trial-and-error (although they also cost about a third of the price). And, even with a good fit, these shoes tend to be a bit stiff out-the-box. Maybe not for your average, everyday shoe customer, but designed for someone who knows the payoff in the end.

The other issue is that, even with the pret-a-porter program, you have to stay close to their standard lasts. For me, the Classic is the only one that really appeals – the others are too pointy. I wish they had some rounder, more conservative lasts, which I think would go better with their casual loafers, derbys, and boots. At their core, many Saint Crispins look best with traditional two-piece suits, which can leave those of us in sport coats feeling cold. That said, even with their Classic last, I love their chukkas, two-eyelet derbies, half-brogues, and split toes (especially the split toes). The Armoury also recently developed a special loafer-only last called the Doak, although I haven’t tried it.

The other issue is the leather. Most of Saint Crispin’s leathers are what’s known in the trade as “crust,” which is a sort of unfinished leather that’s colored at the workshop using dyes. By using crust leathers, shoemakers can buy large quantities and get whatever color they need – black, tan, brown, green, or even a dazzling purple. All it takes is a bit of dye and some elbow grease. This helps lower the cost of the leather itself, as well as save on much needed space inside small workshops.

For the customer, there are upsides and downsides. The upside is that crust can age beautifully, getting a sort of depth in the color not easily achievable in normal leather (see my wingtips above). The downside is the leather also requires a bit more upkeep. Shoes can easily look dull after a few wears, and you’ll want to be careful with which sorts of conditioners you use (a bit of Saphir Renovateur once wrecked my crust leather chukkas, although Saint Crispin’s was able to fix them for me). To get that beautiful luster you see in Ethan Newton’s photos, you need to shine them somewhat regularly. Again, maybe not for your average, everyday shoe customer, but possibly a good choice for the enthusiast.

The company’s shoes aren’t for everyone – it takes a bit of work to think through the options, as well as discipline to get through the first few stiff wears. That said, the right pair can look great with tailored clothing. You can order them through Skoaktiebolaget, Leffot, M Classic 101, The Armoury, Michael Jondral, Bryceland’s, and Saint Crispin’s themselves. They’re admittedly expensive, but if you like the shape and flexibility you’d get out of traditional bespoke, Saint Crispin’s represents a unique value.

(photos via me, Saint Crispins, Skoaktiebolaget, Sartorial Beijing, Zachary Jobe, and Oliver Dannefalk)