More than ten years after menswear blogs were all about sick fades and selvedge stripes, a pair of raw denim jeans is still one of the most useful things you can add to your closet. Nevertheless, I’ll admit to having some denim editorial fatigue. With the spate of slapdash Kickstarter projects and indistinguishable denim start-ups, it’s hard to get excited about new companies. I yawn every time I read about how some made-in-USA company is using Cone’s White Oak denim.

Blackhorse Lane Ateliers, however, is different. For one, unlike most denim brands, Blackhorse actually manufactures things. They’re a London-based factory, originally having started in the early 1990s. Han Ates, the factory owner, handled clothing production for various high-street labels, making everything from men’s dress shirts to women’s dresses. When those companies asked him to move their production to Turkey, however, he did. And when they asked him years later to move their production to China, he complied. It wasn’t until they asked him to move to Vietnam that he quit. As he puts it, he got “tired of feeding the fashion beast.”

Han left the fashion world to pursue a career in the restaurant business – opening a small, Mediterranean brunch spot in London – but it wasn’t long before he found himself back in the rag trade. He missed the creative side of the work, so he picked up where he left off, co-founding Blackhorse Lane Ateliers with Toby Clark, a former menswear designer at Margaret Howell.

The factory is in the same, charming 1920s building that Han has always owned. When he originally moved production out of London, the factory was converted into a storage facility for his business and other fashion houses. Now, it’s started up again, with sewing machines chattering away to make raw denim jeans, canvas totes, and workwear jackets.

David Giusti, the company’s Head of Digital and Retail, tells me they have three verticals to the business. “We do private label work and occasionally engage in collaborations. We’ve made denim aprons for Labor & Wait, then jeans for Drake’s, Christopher Raeburn, and Ben Sherman. That last one featured hand-sewn chain stitching by our friend Charlotte Willingale.” Of course, there’s also the house label, Blackhorse Lane, which helps fill out the production schedule when other companies don’t need anything (a danger for any factory, as fashion works on a seasonal cycle).

More than just a factory, Blachorse Lane is also a community space. “Han was inspired by the craft revolution he saw in the food industry, so he’s applied those principles here,” says David. On one floor of the building, you can find the company’s workwear production. On another, there are artist studios – currently occupied by art restorers, fabric weavers, and workwear designers.

In addition, the building hosts workshops, where people can come during the evenings to learn how to dye shibori (a Japanese form of tie dye) and sew their own jeans. During the latter parts of the week, there’s a pop-up restaurant event called “Denim & Dine,” where a local chef serves a multi-course tasting menu in Blackhorse’s East London factory (video below).

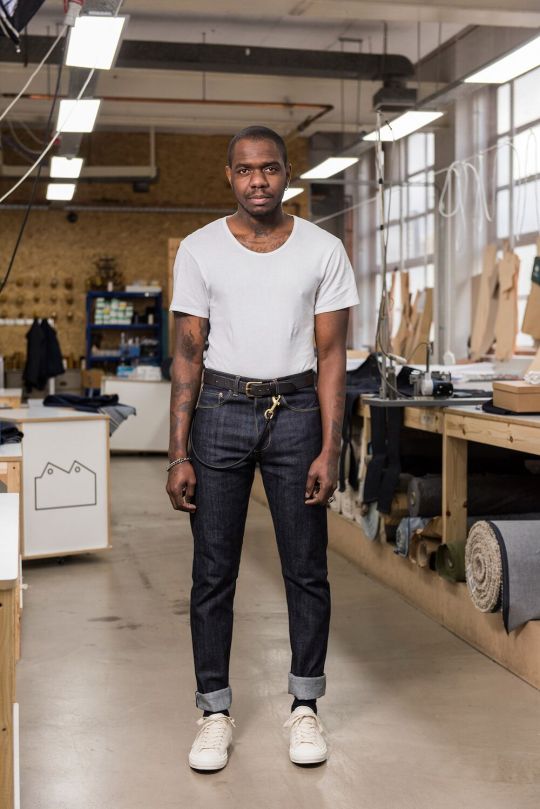

Of course, none of this would mean anything if the jeans themselves weren’t any good. And on that front, they’re outstanding – with a level of quality and service I haven’t seen at this price point before. Blackhorse Lane has four main fits, each of which is named after a certain London postcode. Their NW3, for example, is a slim straight-leg designed after the kind of heritage looks you might find in Hampstead. The E8, meanwhile, is a skinnier tapered cut you might see in the more fashion-forward area of Hackney.

Construction wise, Blackhorse incorporates some surprising details you’d normally only find in tailoring. Whereas most denim companies stay true to their workwear originals – and thus finish their jeans with quick, overlock stitches – Blackhorse constructs everything with single-needle stitching and felled seams, making the interiors as handsomely constructed as a good pair of trousers. Additionally, they use a single-piece fly (shown in the video at the end of this post). On most jeans, you’ll find a two-piece fly that’s held together with a bar tack. It’s a perfectly good way to make a fly, although the one-piece construction here looks cleaner and nicer.

Even with the more labor intensive details, Blackhorse jeans start at £150 (roughly under $200 USD). Take roughly 20% off for VAT, however, and an additional 17% off for first-time buyers who subscribe to their email list, and you’re looking at $132 – a price unheard of for jeans with these details. More incredibly, the company offers a lifetime service of free repairs. Darning is done on a 1920s Singer machine, although customers in the US will have to ship their jeans to London. I spend about $50 a year in denim repairs alone, which over the course of three years, is basically a free pair of jeans here.

Some of my favorite jeans lately are from Drake’s – the company’s No. 3 model, which is made by Blackhorse. They’re modeled after the company’s NW3 fit, but with some small modifications (a slightly more tapered leg, I’m told). They’re also the first pair of jeans I’ve owned that works as well with casualwear as it does with sport coats (most jeans have a rise that’s too low to go with tailoring). Leave it to Michael Hill and his team to find new companies for me to love. Blackhorse Lane is one of the more exciting denim start-ups I’ve seen in a while.