I had a project last year where I wanted to re-line a black leather jacket with an old piece of Japanese boro – a term used for heavily repaired, indigo-dyed peasant fabric that comes out of the island’s countryside. The project hasn’t gone so well. Although I found my boro (it was bought at Shibui), I haven’t found the right jacket. The original plan was to get a cafe racer from an old season by Junya Watanabe, but after ordering one direct from Japan, it was lost in the mail. So, the boro sits neatly folded in my closet, waiting for another jacket to arrive.

The process has gotten me interested in other textile traditions, however. Re-lining something such as an old cotton field jacket or a beat-up leather bomber seems like a nice way to (quietly) incorporate fabrics that might otherwise never get used in men’s clothing. One area of interest at the moment: African textiles – namely mud cloths and indigos, although since these traditions are so varied and intricate, I’ll only highlight the latter today.

Western Africa, both along the coastal regions and further inland, has an incredibly rich history with indigo. The noted Arab traveler Ibn Battutah once visited Kano, an ancient trading city in northern Nigeria, where he remarked on the indigo dye pits of Kofor Mata. Nearly seven hundred years later, those same pits are still being used today.

In Africa, indigo is typically prepared through one of several methods: either fresh leaves are steeped in a wood-ash lye in vats or deep pits, which are set into the ground; or they use balls of dried leaves that have been either kept back from harvest or acquired through trade. The fabrics that are dyed are usually mill-woven cottons, either locally made or imported, which they decorate through a variety of dye-resist techniques – including tie dye, stitched and folded resist, wax batik, and starch resist. John Gillow highlights some of these techniques in his wonderful book African Textiles: Color and Creativity Across a Continent. Some excerpts below, taking my favorite examples.

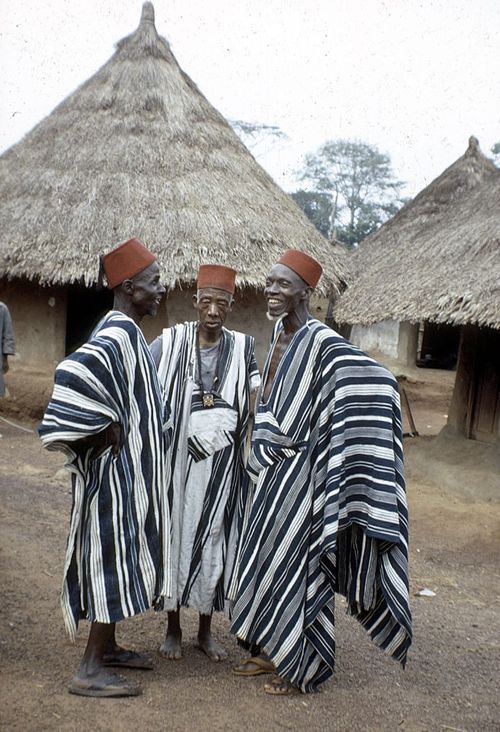

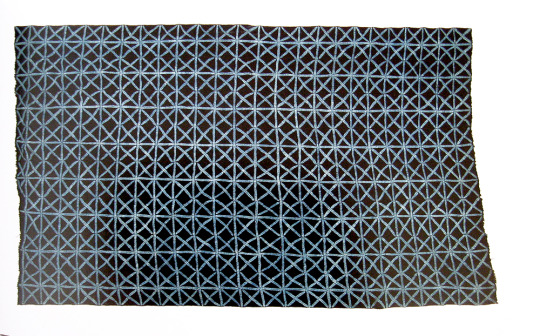

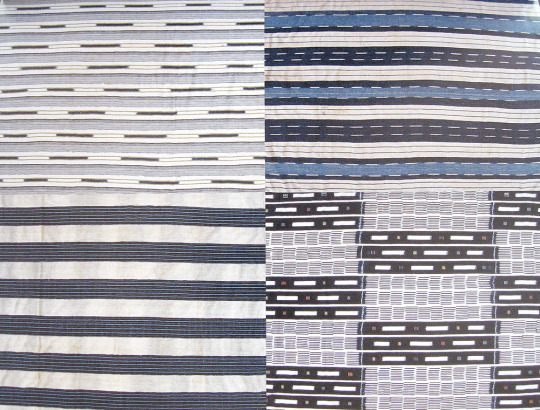

Here we see some stripwoven cloths, woven from indigo-dyed cotton thread and decorated with white cotton detailing. Stripweaving refers to a technique where strips of fabric are sewn together – selvedge to selvedge. Whether stripweaving is an adaptation of a technique that crossed the Sahara or is indigenous to West Africa is a matter of speculation, although by the 18th century, complex stripweaves were being created in Kong (located in the present-day Ivory Coast). The wealth afforded by the gold trade at this time enabled the king and members of the court to commission sumptuous and densely patterned stripweaves, which were both worn and used for home decoration.

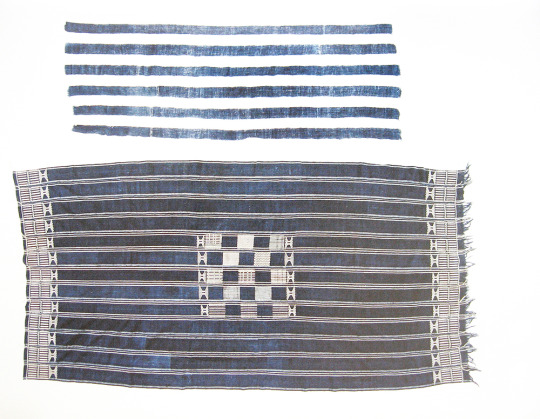

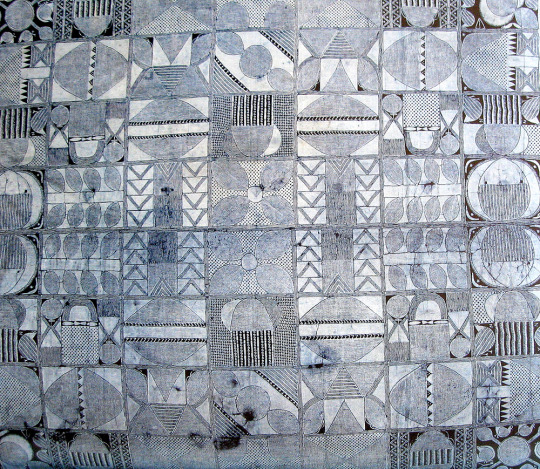

Here we have Nigerian tie-dye. Known as adire oniko (meaning tied resist), these fabrics are typically used by Yoruba women as head wraps. Small wraps are first folded, then tie-dyed to create spiral designs. Beans, grains of rice, chips of wood, stones, and twine are sometimes creatively used to create interesting designs. The top photo shows what’s known as a Three Baskets pattern – named so because of its bold, concentric circles, which are made up of tiny dots.

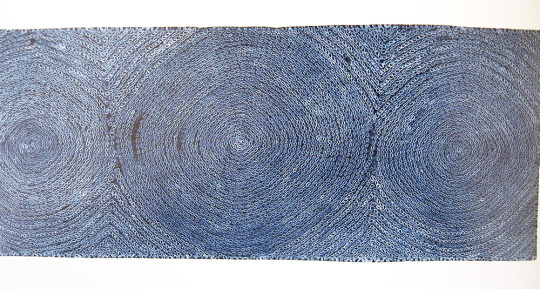

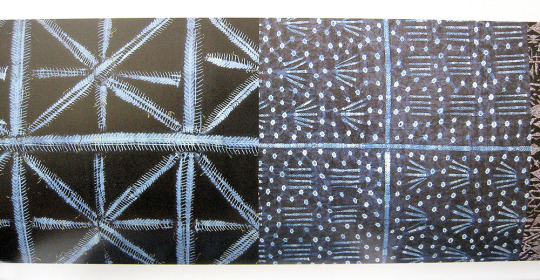

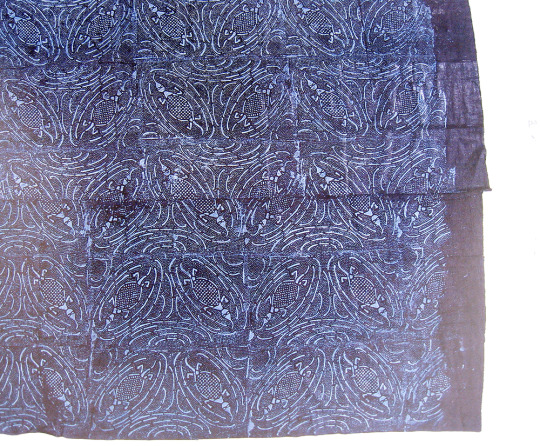

These stitched-resist fabrics are from Mali and southwest Nigeria. One of the ways to create designs is to stitch the fabric before it gets dyed – using either a running stitch or oversewing stitches. That way, when the thread is tightly pulled, the fabric compresses and resists the dye. The part of the fabric that is to be dyed is normally first doubled up or pleated, to create a symmetrical pattern and also to reduce the amount of work involved. When the stitches are removed with a sharp blade, the fabric is then opened and the pattern is revealed. When sewn, some of these patterns are so intricate that they could be rightly classified as embroidery.

Some more stitched resist fabrics. The bottom is a Yoruba woman’s wrap, where strips of mill cloth have been resist sewn with a strong raphia thread, dyed blue, and then carefully unpicked. The strips have been sewn together, selvedge to selvedge, to give the impression of the more prestigious (and expensive) stripwoven cloth.

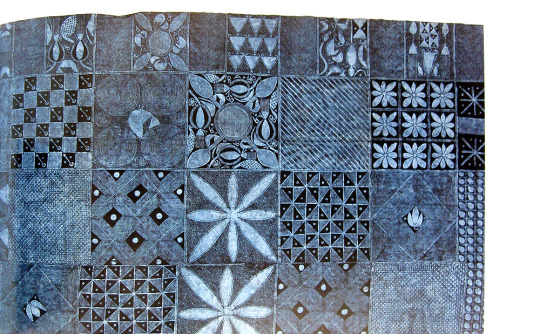

Possibly the two most impressive examples of African indigo fabrics in the book. These two are both stitched resist fabrics from Nigeria. Just look at the fineness of that detailing. Curvier designs, such as what you see in the bottom example, typically suggest that the stitching was done by hand. When the person making these fabrics is picking the stitching apart, he or she has to be extra-careful to not let the sharp razor’s edge nick the fabric (which is typically a thin white shirting).

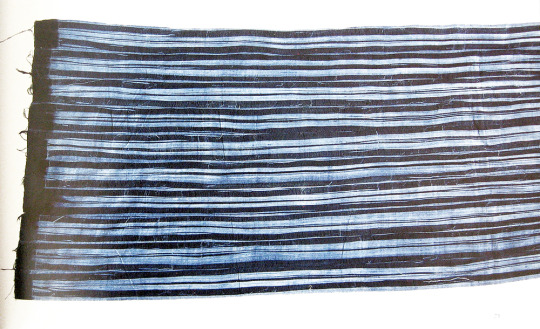

Examples of Yoruba and Baule warp ikats, including a few stripwoven cloths. Ikat is a process whereby the threads are tie-dyed before the weaving process. When the cloth is being woven, any section where the threads have been previously ikat-dyed will have a rather frayed pattern in the color of the undyed thread pressing against the dyed ground. The ikat process can be applied to either the warp or weft yarns (or both), although warp ikat is more common in West Africa.

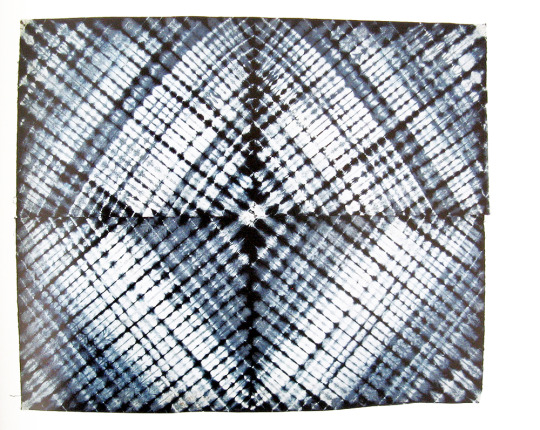

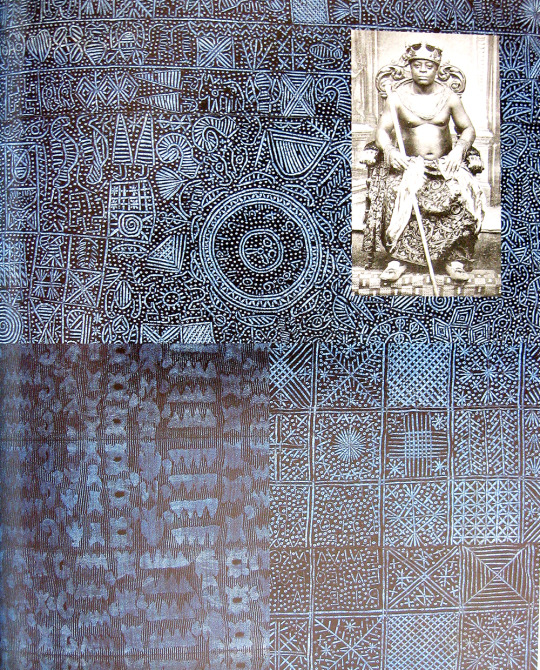

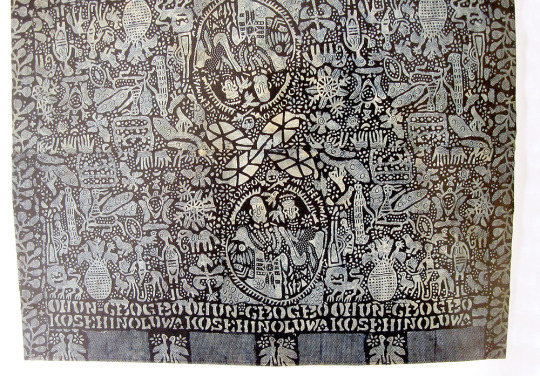

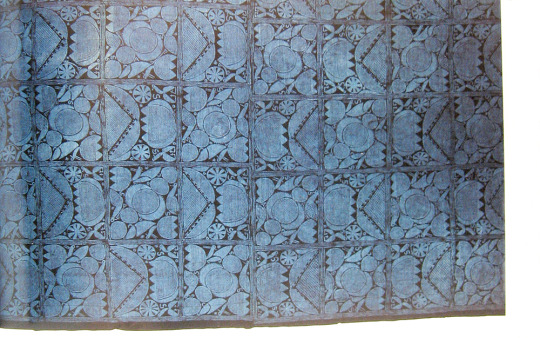

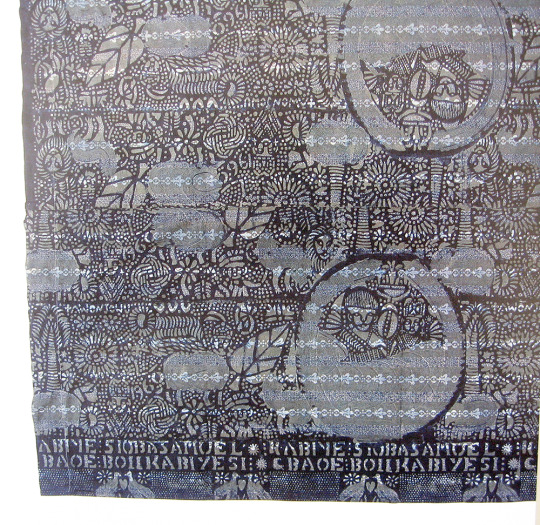

In the early 20th century, there was a fashion for adire eleko (starch resist) fabrics amongst certain Nigerian Yoruba women. These had a cassava starch-resist paste applied to them by hand before they underwent any dyeing. Patterns typically featured birds, lizards, and well-known landmarks. After the 1920s, the cloth went out of fashion, only to be revived again in the mid-century by expatriates in the country. Today, it’s largely disappeared given the low-demand.

When it is made, however, it’s done by dipping a sharpened quill into a paste of cassava flour mixed with copper sulphate and water (which together makes what’s known as lafun). The artist then folds the fabric a few times in order to build out a series of squares, then unfolds the cloth and begins filling each of the squares with a design (using the lafun).

The cloth is then dip-dyed in an indigo bath as many times as necessary to achieve a deep, blue-black color. In between each dipping, the cloth is laid out on a rack to dry. Great care has to be taken to make sure that the lafun doesn’t crack. Since the paste doesn’t resist the dye completely, the cloth takes on a light-blue pattern against a dark-blue background once the process is done.

More indigo-dyed, starch-resist fabrics. The one at the top is a hand-drawn design imitating the stenciled King George V and Queen Mary pattern, originally created for the occasion of their Silver Jubilee in 1935. The one at the bottom is made up of two distinct motifs, conveying the message “I’m getting myself together.”

Starch resist patterns are sometimes drawn by hand; other times, they’re made with stencils. In the early 20th century, these stencils were first made from the lead linings of tea and cigar boxes, but for the most part, Nigerians have used zinc panels (typically 2 inches by 8 inches). The designs are chiseled into the metal, and then placed over the fabric, so that the starch paste can be squeezed through and applied.

For ideas on how to incorporate African indigo into a wardrobe:

- You can take any of these fabrics and use them to re-line a jacket. Probably better for casualwear, such as a field jacket or bomber, and probably a good idea to make sure the dyes are colorfast (so they don’t bleed on your clothes). African indigo fabrics can be bought at Indigo Arts.

- Post Imperial also makes traditional four-in-hand neckties from Nigerian, Yoruba-made indigo textiles. On sale at the moment at No Man Walks Alone.

- My friend Walé Oyéjidé started Ikiré Jones a few years ago – a line that heavily draws on African design traditions. Unfortunately, no indigo items at the moment, but they might have something in the future.