When Hubert de Givenchy passed away earlier this year, many noted that his relationship with Audrey Hepburn helped set up today’s fashion-Hollywood complex – a system where designers dress famous faces so they can raise their brand’s profile and move units. Except, the relationship is so thoroughly deformed today, few would recognize the connection. Givenchy and Hepburn had an honest relationship and found in each other kindred spirits. They worked together to craft mutually supportive identities. Givenchy was Hepburn’s courtier; Hepburn was his muse. Today, however, clothiers and celebs work on a pay-for-play basis. Celebrities will profess their undying love for a brand one season, they say they like something entirely different the next.

One of the few exceptions is Daniel Day-Lewis, who by all accounts has a genuine interest in style. He’s a second-generation Anderson & Sheppard customer and once studied shoemaking under the late Stefano Bemer. In preparing for his role in Phantom Thread, where he played the fastidious courtier Reynolds Woodcock, Day-Lewis learned how to cut, drape, and sew – at one point even recreating a Balenciaga dress all by himself (I admit to being skeptical, but that’s what was reported). George Glasgow Senior, of renowned British shoemaking institution G.J. Cleverley, tells me that when the actor is in London, he often stops by the shop to talk about shoes. “He has a keen eye and a very strong interest in clothes,” he says.

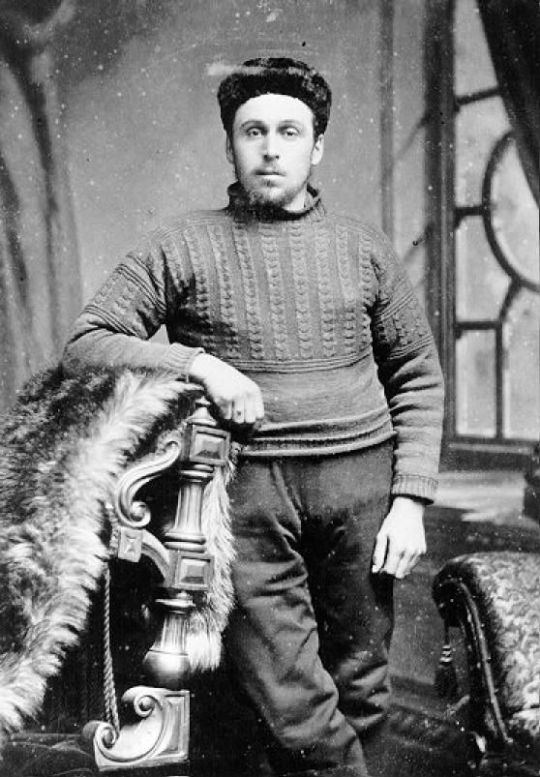

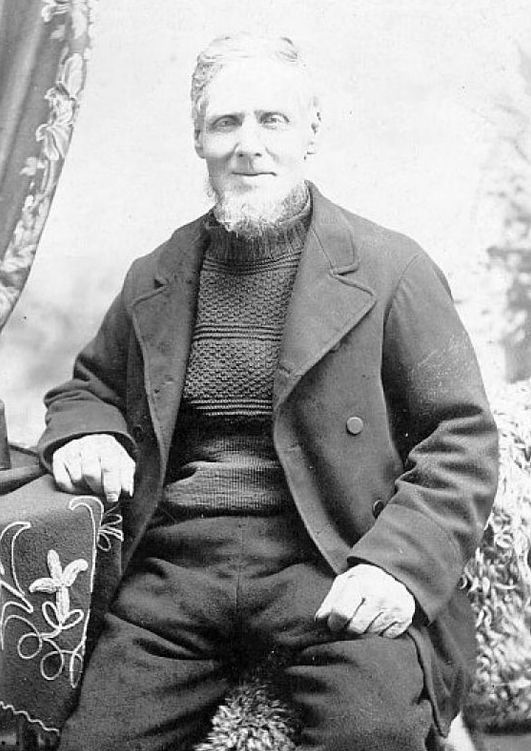

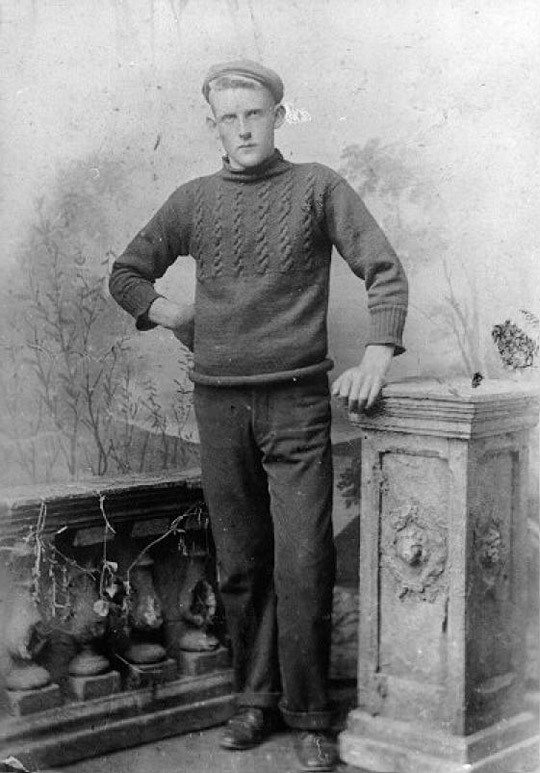

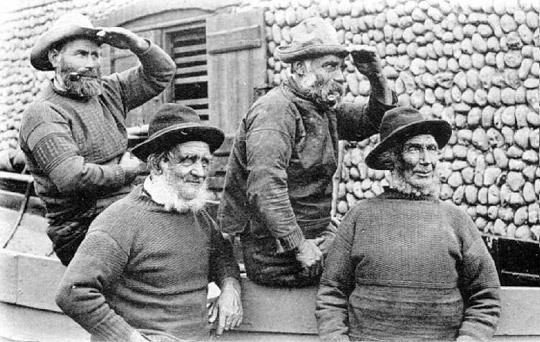

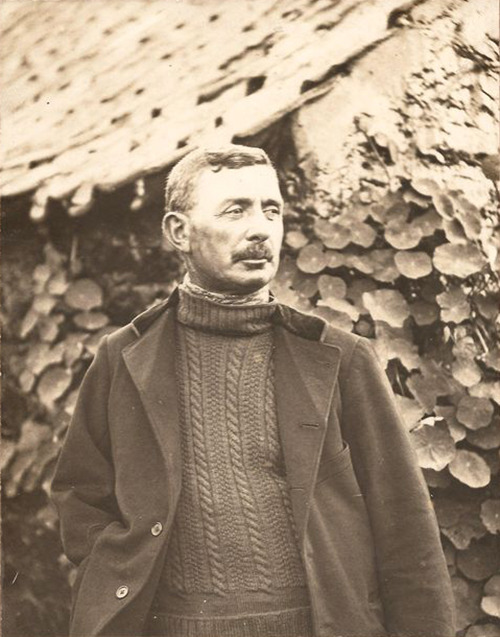

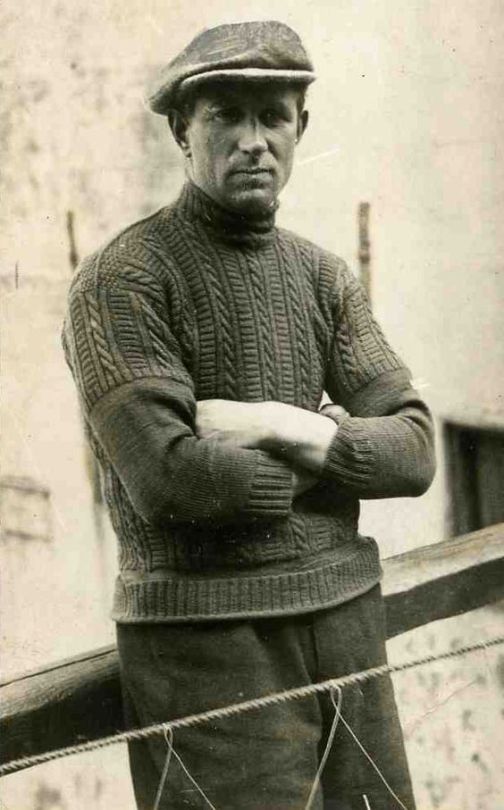

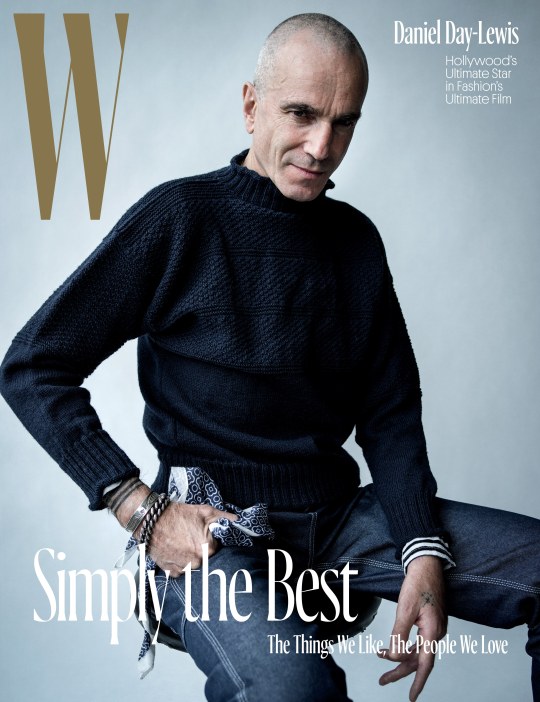

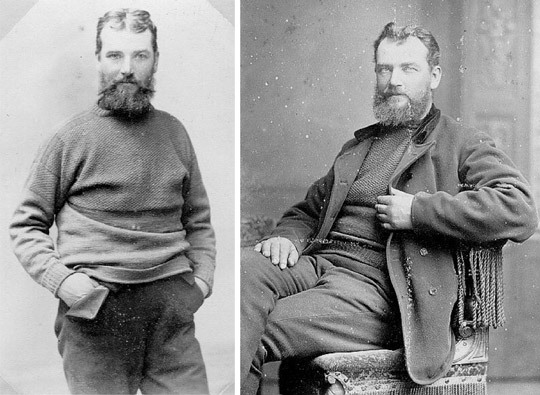

So it was great to see Day-Lewis wearing the fisherman sweater pictured above, knowing it came from his wardrobe and that he had chosen it sincerely. The photo is from a W Magazine cover story published earlier this year. In it, he sports a striped Breton shirt, some heavy jewelry, and a fantastically rugged, moss-stitched sweater fashioned after something he inherited from his father. And true to form, instead of the sweater being supplied by a big name fashion house – who would have gladly paid for such exposure – it was from a small, unknown knitting cooperative located in British coastal town. My friend Pete wrote about it at Put This On: “The sweater caused a stir in knitting circles, and the knitters got to the bottom of it. His sweater, apparently, comes from a maker called Flamborough Marine, an outfit that still makes the sweaters entirely by hand.”

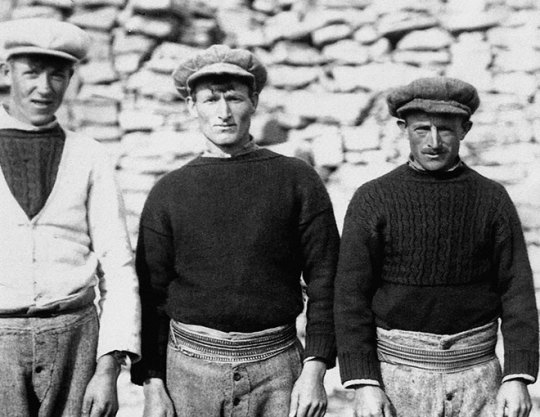

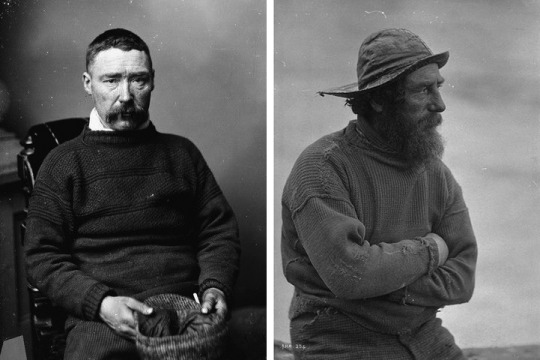

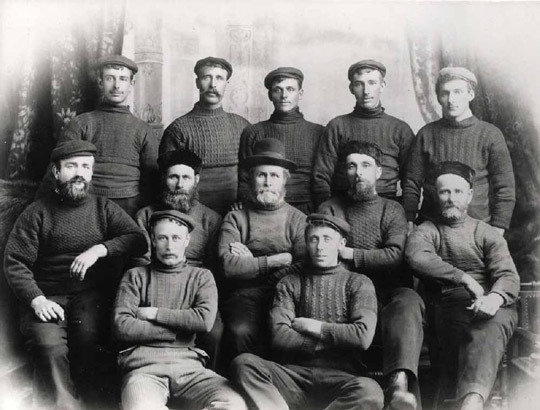

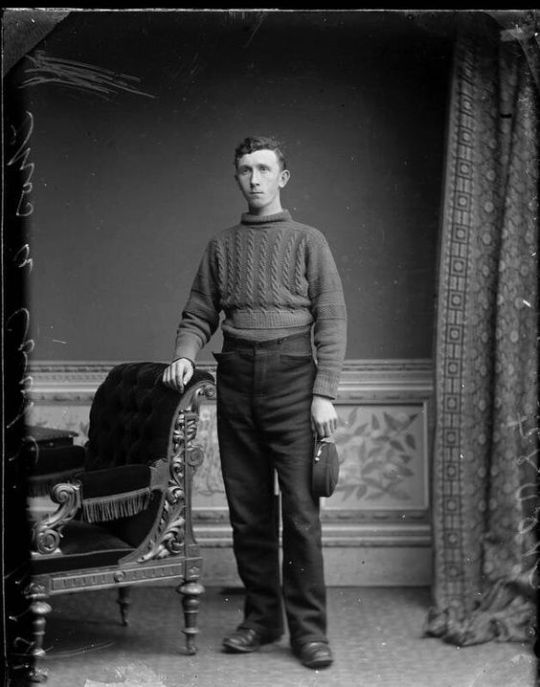

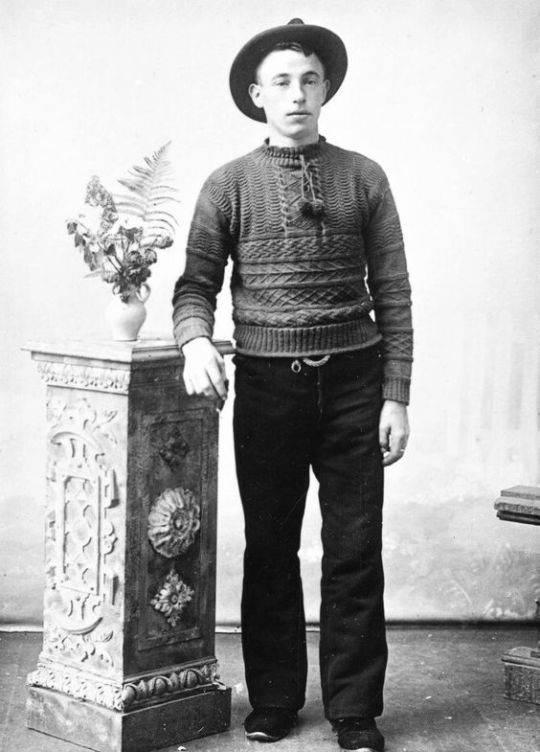

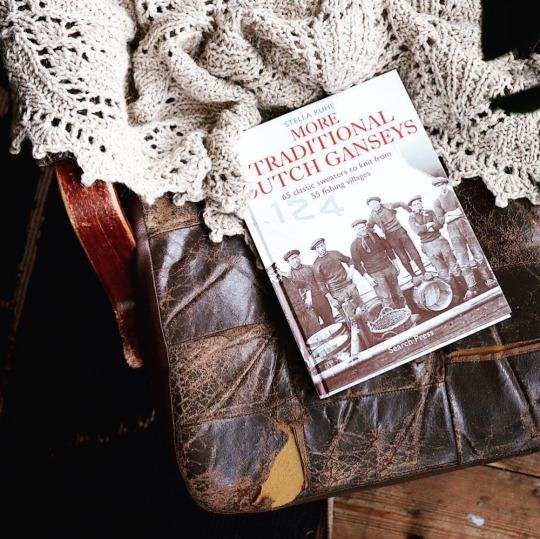

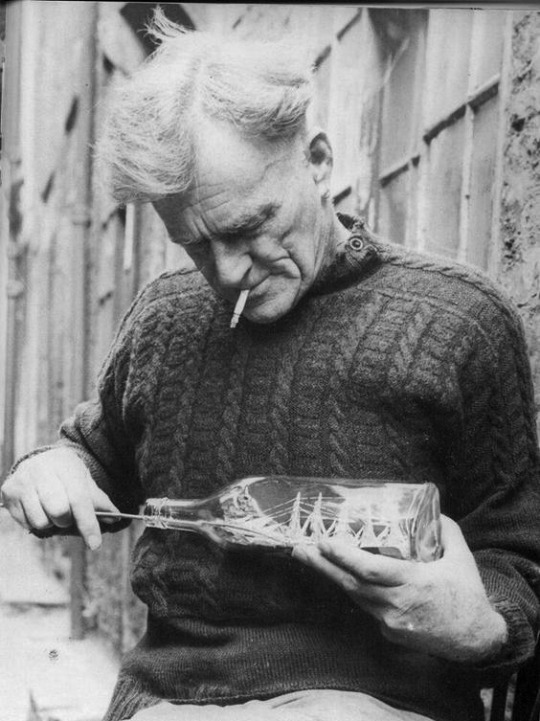

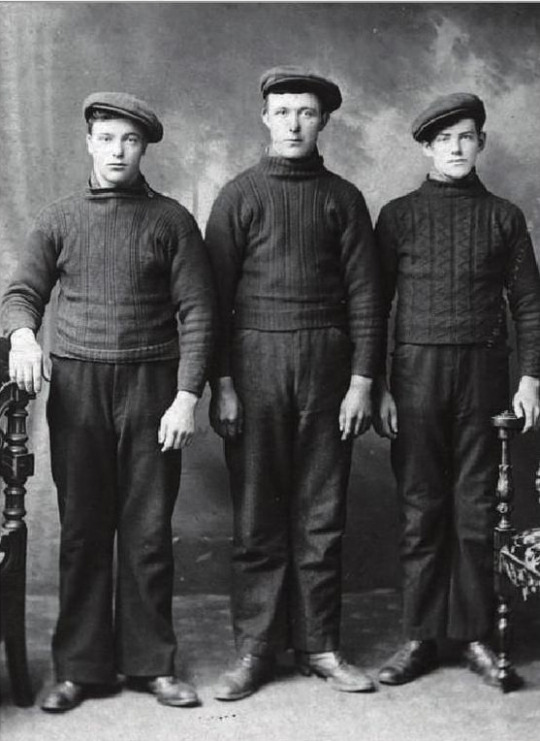

The knitwear style is one of the two that comes out of the region’s fishing communities – the other being the Aran. This one is called a gansey, or sometimes guernsey. Some say the word comes from Guernsey, one of the Channel Islands located between France and England, where many of these sweaters are still produced today. Others say it’s an Anglicized corruption of geansaí, the Irish word for sweater. Either way, as Pete points out, “these sweaters hit all the squares on the ‘coveted menswear’ bingo card – they have a deep history, are designed to be utilitarian, were often handmade, are practical but archaic, and exist at the crossroads of functional design and decoration.”

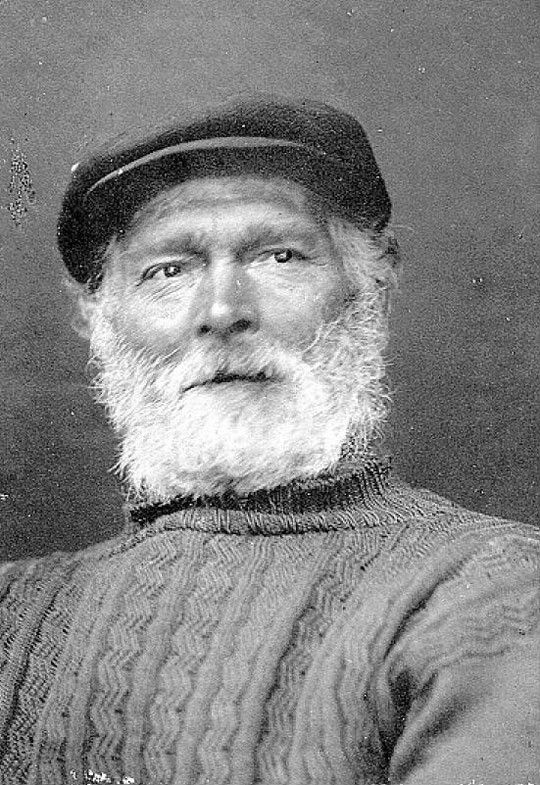

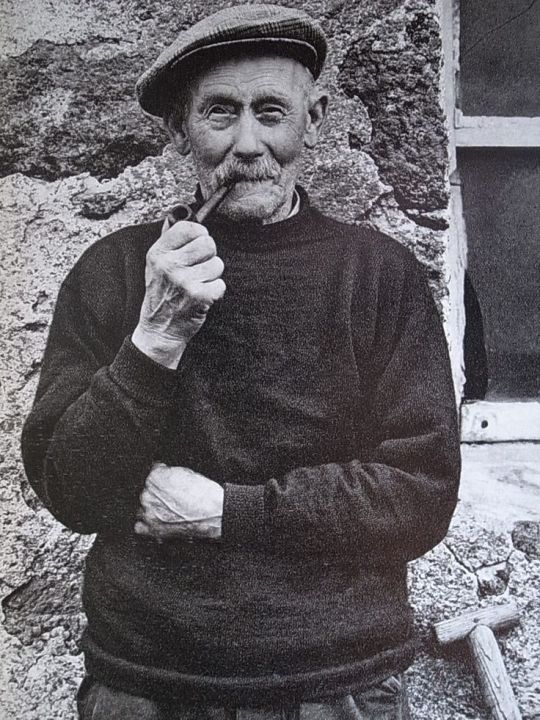

Ganseys have intricately knitted patterns that combine stitching techniques inspired by seafaring life: cables, pebbles, netting, herringbone, ladders, and so forth. Other patterns are of religious or symbolic nature, such as Christian crosses or church windows. Supposedly, individualized patterns came to be associated with specific home ports or families, which allowed people to identify the poor, dead bodies of drowned fishermen who had been lost at sea or washed ashore.

When it comes to menswear history, it’s hard to separate truth from fiction. The two are often intertwined in marketing pamphlets and vanity books, and the stories persist because they help sell clothes. For example, it’s often said that we got the word blazer because of the British frigate HMS Blazer, where the ship’s captain – who had short, double breasted jackets made from navy blue serge for his scruffy crew – decorated his staff’s uniforms with shiny brass buttons so they’d be more presentable for Queen Victoria’s visit. The story has been retold so many times, we just assume it to be true.

For fishermen knits, however, there are no first hand records of anyone’s body being identified in such a way. The story likely comes from J.M. Synge’s 1904 play Riders to the Sea, in which a girl identifies the body of her dead brother by his plain stockings. “It’s the second one of the third pair I knitted, and I put up three score stitches, and I dropped four of them.” Swinging herself around and throwing out her arms onto his clothes, she cries out, “And isn’t it a pitiful thing when there is nothing left of a man who was a great rower and fisher, but a bit of an old shirt and a plain stocking?”

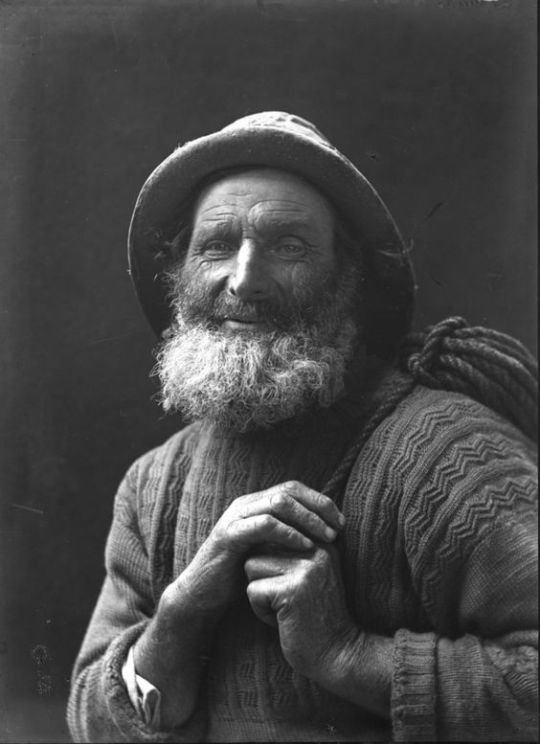

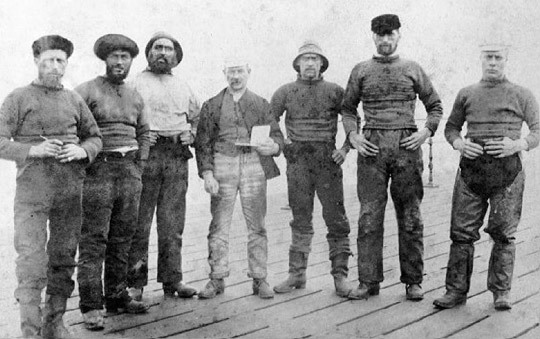

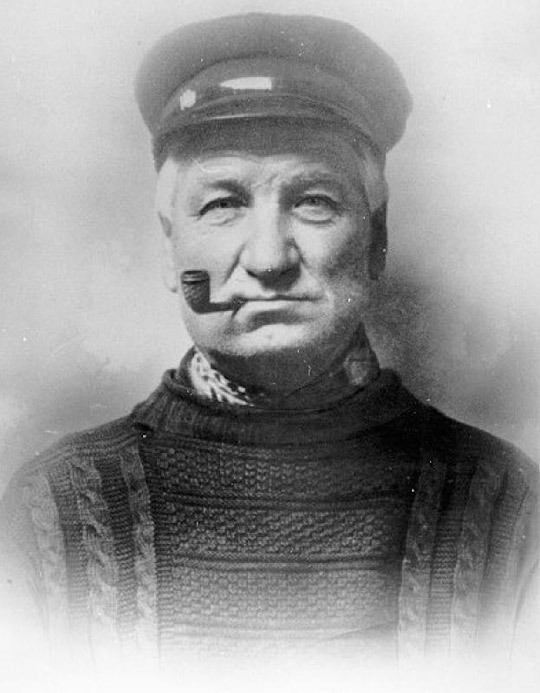

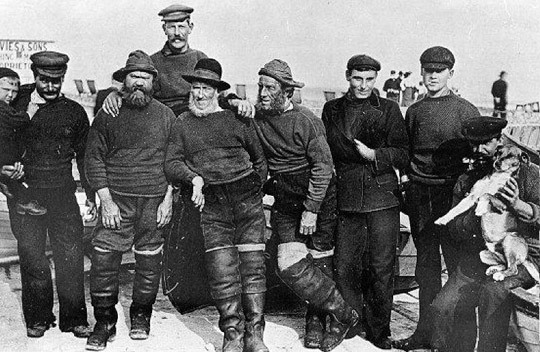

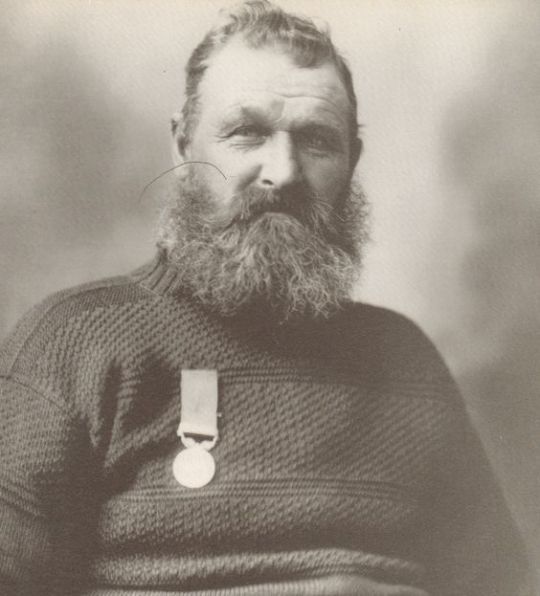

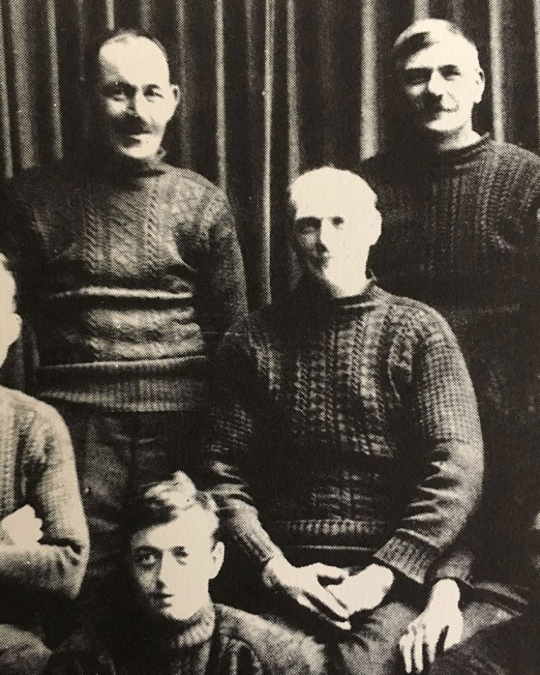

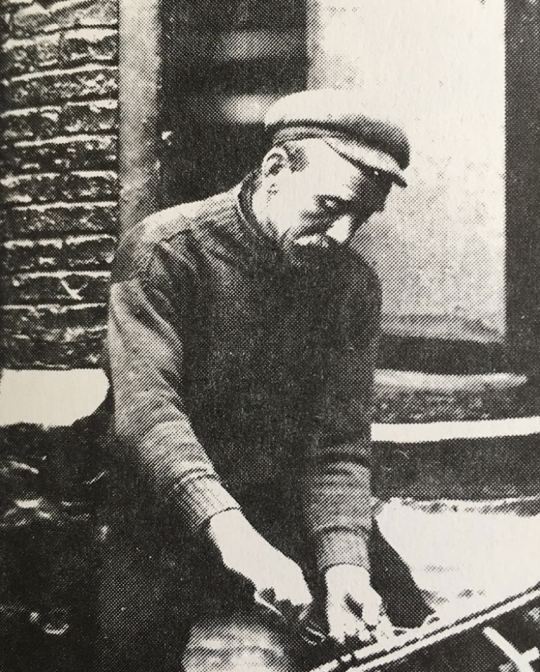

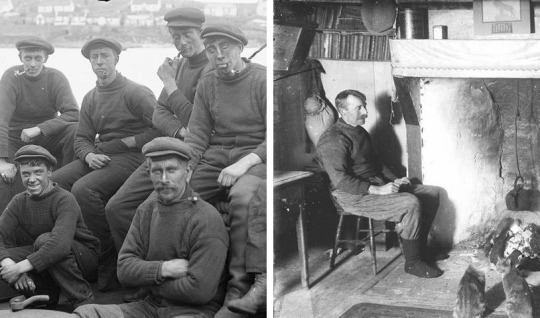

Whether fishermen have ever been identified by their knits, however, may be irrelevant, as these sweaters already have a sweet melancholic sensibility. These were often knitted by the wives of poor fishermen, usually men of Scottish, English, or French heritage, who worked in or around the cold North Sea. The knitting style was first used for socks, and originated during the reign of Elizabeth I. During the Napoleonic Wars, Lord Nelson – who’s the inspiration for Rubinacci’s Victory pocket squares – adopted the sweater as part of the Royal Navy’s uniform. They were also worn at the Battle of Trafalgar and became official naval issue for British officers stationed in Nova Scotia.

Every detail of a gansey is about pragmatism. These sweaters are knitted “on the round,” which means they’re completely seamless, using five or more double-pointed steel needles. They’re constructed from a tightly spun, five-ply worsted wool popularly known as “seamen’s iron.” Being seamless means they’re less likely to break along the sides. And by knitting the sweaters tightly, using densely packed yarns that have been given a hard twist during the spinning process, makers are able to produce a finish that repels rain and sea spray (or “turn water,” as some in the region say).

The patterning of a gansey is also completely identical from the back to the front, allowing a fisherman to get dressed in the dark and, if necessary, turn the sweater around to even out the wear at the elbows. The tightly ribbed cuffs and stand-up mock collar block out harsh winds; the football-shaped gussets placed under the arms allow for easier movement. And since the bottom half of these sweaters are most prone to wear-and-tear, knitters keep the bottoms plain while concentrating their intricate patterns closer to the shoulders. This way, a knitter can pull out and re-knit the bottom if it gets snagged or torn. A useful design feature if you work around sharp-edged barnacles – or, like me, a sharp clawed and trouble-making house cat.

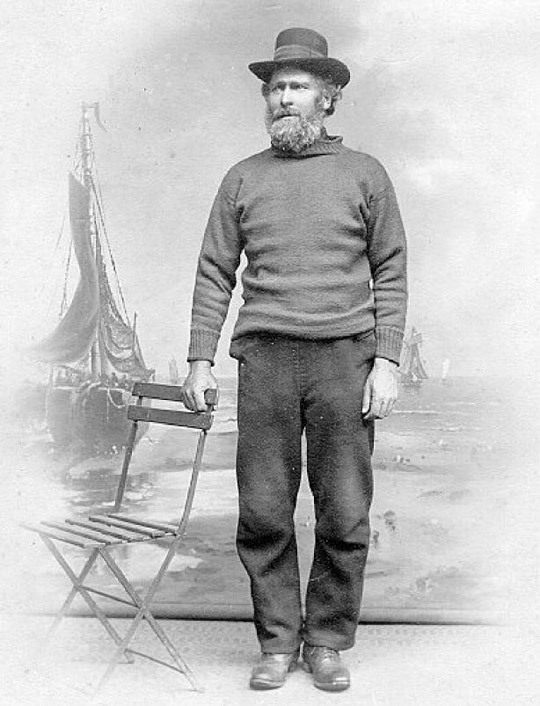

You can tell when a sweater is a gansey from its boxy silhouette and dropped shoulder seams. Workwear versions typically come in deep blue, natural indigo-dyed yarns, while lighter-weight ganseys were made for summer from pale gray or fawn colored wools. Black ganseys were sometimes worn at funerals, while a fancier, more polished version of the style was generally saved for special occasions and Sunday-best attire. Sometimes these were knitted by a lover and given as a betrothal gift.

These sweaters used to be deeply embedded in their communities, with their knitting patterns passed on from generation to generation. But as younger people moved out of fishing villages, they all but died out by the 1920s. Today, the tradition continues, but mostly through a small cottage industry. The sweaters are often machine-made and then finished by hand along the shoulder seams.

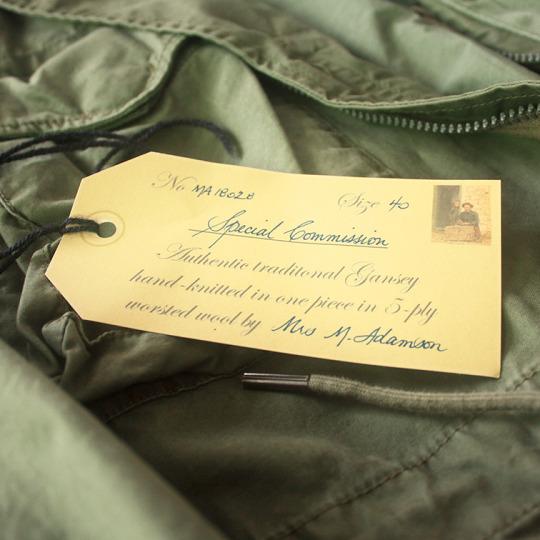

Flamborough Marine is one of the few companies still offering completely handmade versions. They’re painfully expensive – costing between $500 and $750, depending on your size and design – and they require about three months to produce. But I was so in love with the photos of Daniel Day-Lewis wearing his, I finally gave in and ordered one over the summer.

The sweater arrived a couple of weeks ago and feels like densely knitted armor. It’s thick and heavy, like two boiled Shetlands fused together, and is made from a wool that’s rough enough that you’d want to layer this over a long-sleeved t-shirt. It’s too bulky to fit underneath a slim jacket, but it works well on its own or worn under a loosely cut coat. Fishermen used to wear these as their only top garment, so it’s fairly insulating and windproof. And since Flamborough Marine’s version is handmade, the knitting pattern is a little more textured than ones produced on automatic machines.

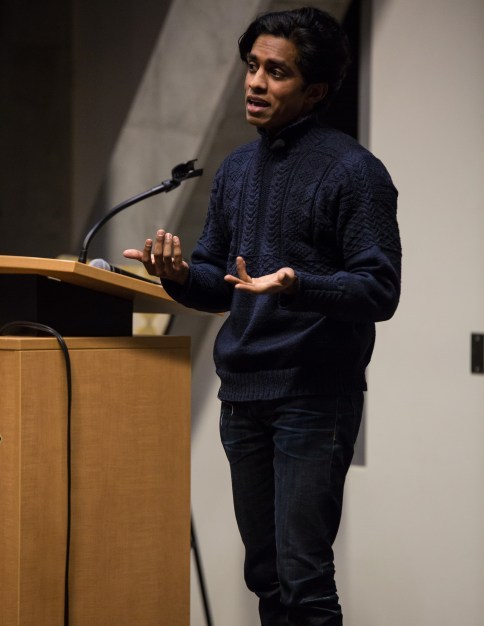

Every one of Flamborough’s sweaters is made-to-order, which means you can customize the knit’s pattern and size. I ordered a size 40″ chest and shaved an inch off their usual length. I also ordered mine to be a full-body cabled version of actor Rajiv Surendra’s sweater (some may recognize him as Kevin G from Mean Girls). Surendra’s a big fan of the knitting co-op and has ordered three of their knits. He glowed about them on Instagram: “These were knitted by wives, children, and the fishermen themselves, not as a leisurely activity, but as an essential part of the day’s work – often while walking or waiting for the kettle to boil. My ganseys were knitted for me by 89 year-old Marion Brocklehurst of the Flamborough Marine. I love them to bits.”

There are more affordable ganseys. Prada and Helmut Lang have produced knits with references to the style in the past, while RRL and Inis Meain have more recently released versions. Le Tricoteur and Guernsey Woolens are a little cheaper, with the first often described as the most “classic” option. J. Crew’s 1988 rollneck isn’t really a gansey, but it has a neckline that’s reminiscent of mine below. S.N.S. Herning has the moss-stitch texture of many ganseys, but not the dropped shoulder line (just be sure to size up). All of these will fit cleaner than a Flamborough Marine sweater, which will have a more “rustic” and idiosyncratic quality (which can be a good or bad thing, depending on what you’re looking for – a hand-knit is going to be a hand-knit). Either way, whether worn with jeans or wool trousers, a tailored topcoat or field jacket, a gansey is a nice option for keeping warm this season. Even if you only ever fish for compliments.

(my Flamborough Marine sweater pictured above with 3sixteen SL-100x jeans, Polo Ralph Lauren field jacket, and Alden cigar shell cordovan boots)