If you were to shop for a cashmere sweater today, you’d be buried in options. Over at Mr. Porter, you can find nearly 250 models, ranging from chalky pastel turtlenecks to NBA intarsias selling for about $1,750. More affordably, J. Crew’s “Everyday Cashmere” collection retails for just under $100, and it comes in Kelly-Moore-sounding colors, such as “rustic amber” (which is orange) and “safari fatigue” (which is green). You can even find cashmere pullovers nowadays at Costco. They’re located somewhere between the aisles for bulk Cheerios and 98″ plasma screen TVs.

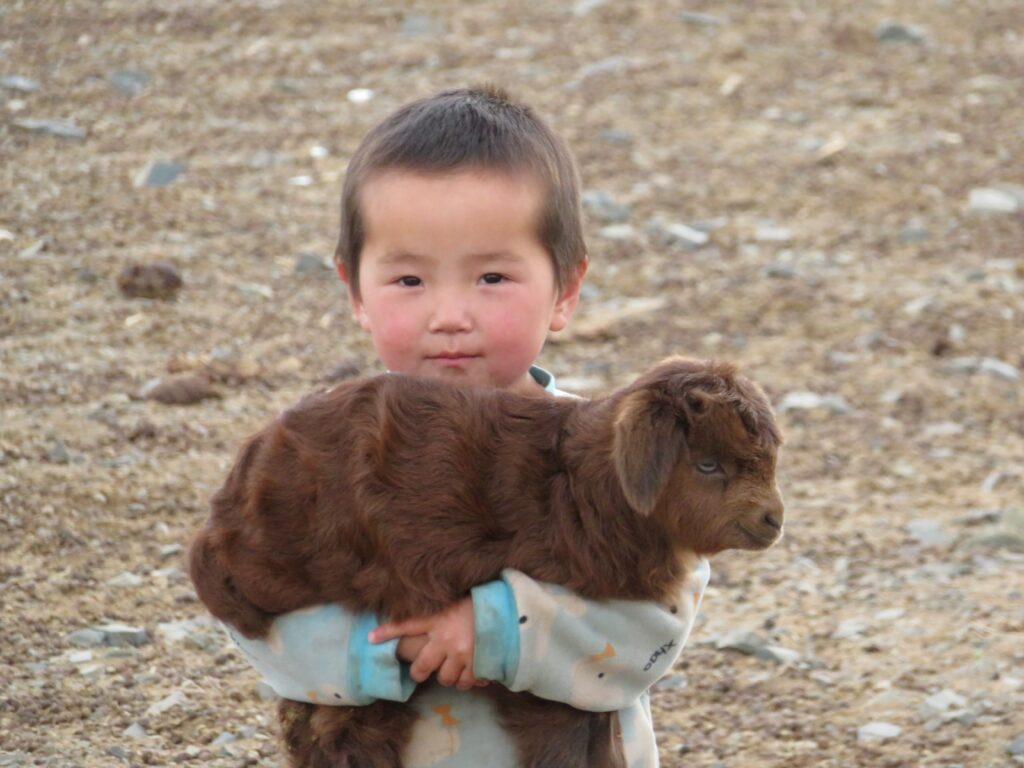

The newest name in cashmere is Naadam, a young upstart promising to deliver luxury sweaters for less than what most stores pay wholesale. They have a over a dozen videos on YouTube, which charmingly pitch their story as two young guys from New York City who made it out to the hinterlands of Mongolia. There, they get stranded somewhere outside of the nation’s capital, ride old motorcycles, and drink goat-milk vodka with nomads. A year later, they return to the Gobi desert with $2.5 million dollars in hand and the bold idea to buy cashmere direct from herders, so they can cut out the middlemen and start a direct-to-consumer knitwear brand. This, supposedly, is how they’re able to offer cashmere sweaters for $75. In every one of their sleek, expertly produced videos, a little baby goat bleats (that’s always the best part).

Until recently, the cashmere trade remained mostly unchanged for the last five hundred years. From the mountains up Tibet and away across the back of the Himalayas to Bokhara, cashmere traveled much like the way it did before Marco Polo explored the Great Silk Roads. It came down from the mountains in countless little loads on the backs of yaks and horses – sometimes buoyed down interminable waterways on rafts and boats – before reaching a major hub, where it’s put on modern transport and swiftly whisked away to another country. If you’re wondering why cashmere should have to travel so far across Asia, just remember the stories of the still unconquered Everest. Across the vast barrier of the Himalayas, there are few routes.

Cashmere has been prized since at least the Roman Empire. It was traded along the Silk Road, where caravans delivered finely spun shawls produced by Kashimiri artisans. Kashmir, which is the valley region near the Himalayas, is actually how we got the name for this fiber – even though very little cashmere is produced there. Still, by the 19th century, Beau Brummell started a trend for white cashmere waistcoats for men, and French empress Eugénie de Montijo wore cashmere shawls that were so delicate, it’s said they could be drawn through a ring. A hundred years later, a Scottish mill owner named Joseph Dawson found a way to mechanically process the cashmere fibers he bought from China. This was the start of the Scottish cashmere industry and how we eventually associated cashmere cable knits with blue-blood traditions.

For much of this time, cashmere was considered a stable and stodgy business, but in just the last few decades, it’s been swept up by fast fashion like everything else. Americans bought nearly 10.5 million cashmere sweaters from China alone last year – fifteen times the amount of what they bought a decade ago, and more than what they imported last year from Italy and the United Kingdom combined. Most of these sweaters retail for around $100, but you can find them for as little as $20 on sale.

It should be no surprise that none of these sweaters are any good. Since quality cashmere is expensive, that means cheap cashmere sweaters have to cut cost somewhere – either by knitting with a lot of slack and/ or using cheaper yarns. Cheap yarns are made from shorter fibers, which means you’re more likely to get those microscopic breakages, resulting in fibers flying up and tangling into each other (what is known as pilling). Jeremy Kirkland of Blamo!, an excellent menswear podcast with an active Slack channel, said he wasn’t impressed with the Naadam sweater he handled. “It felt thin and pilled easily,” he said. “The finishing also left a lot to be desired. I admire that they work directly with herders, but I would put their quality below Uniqlo and J. Crew.”

Of course, consumers go into these deals half-expecting the sweaters to not be very good anyway. But the material feels too soft and irresistible in stores, and when discounted far enough, they’re basically must-buys. At $50 or $75, if they pill or lose their shape, buyers shrug and replace them with something new. Four hundred years ago, the average person couldn’t even dream of touching cashmere, but nowadays, these sweaters are treated as semi-disposable items.

The story of cheap cashmere has two parts: one of the consumer side, the other on the supplier side. The first has to do with the burgeoning appetite for cheap imports, particularly in the West, which has kept cashmere products moving. The second is about structural changes in the political economy of countries halfway around the world. Roughly eighty percent of the world’s cashmere is grown in China and Mongolia (including the top-end stuff). And it’s been the liberalization of these two countries that has sent cashmere prices spiraling downwards.

In 1991, Mongolia started their liberalization program, after having been a socialist state for nearly seventy years. By 1994, about 200 state farms and 325 agricultural cooperatives passed into private hands. Herdsmen took control of the country’s agricultural assets through a voucher program (much like the reforms in the Soviet Union, except without the asset stripping). This, coupled with the collapse of Comecon and the liberalization of Mongolia’s exchange rate, led to a huge boom in cashmere production. The country nearly doubled their cashmere output from 1991 to 1994 – going from 1,400 to 2,500 tons. And since Mongolian herdsmen no longer had to prematurely kill their livestock to feed the Soviet state, the number of goats in the country exploded.

There have been some hiccups along the way, but they’ve only contributed to the worldwide glut. In 1997, the Japanese economy was hurt by the East Asian financial crisis, so consumers there demanded less cashmere. But this just meant that the already-produced products had to go somewhere else – namely the West, where buyers enjoyed lower prices and developed even more of a taste for the noble fiber. Today, China has stockpiles of raw fibers sitting unused in warehouses. Yet, they continue to produce cashmere because they need to keep farmers employed.

The fashion victim in all this has been the environment. While collective farms and livestock have been passed into private hands, the main input in this trade – namely, pastureland – is still mostly treated as a public good. Goats have to eat grass in order to grow hair, but that just means that the state allows private herders to use certain parts of the government-owned pastureland at certain times. This has transformed once-lush grasslands into arid moonscapes, unleashing some of the worst dust storms in East Asian history, as well as a spoiling of the region’s water, soil, and air.

It has also affected the goats. Evan Osnos of The Chicago Tribune once wrote about how these scrawny, little animals would trudge into view when he visited the plateaus of China, where cashmere is farmed.

Their wispy coats fluttered in the wind. They limped up a hill and slumped to the ground around him. They were starving. This stretch of China’s mythic grasslands, one of the world’s largest prairies, is running out of grass. The land is so barren that Shatar and other herders buy cut grass and corn by the truckload to keep their animals alive. Goats are so weak that some herders carry the stragglers home by motorcycle. Shatar expects most of his goats will live 10 years, half the life span of their parents.

The animals’ birthrate is sinking, too. Shatar once had 100 new goats each spring. This year he got 40. Even the cashmere has begun to suffer. Hungry goats are sprouting shorter, coarser, less valuable fleece.

Since Mongolia started their reforms, the number of goats in the country has soared. In 1991, it’s estimated that there were 5.2 million; in 2004, it was 25.8 million. All of them chomping and eating away at the grasslands, forced to breed and grow hair. A 2003 World Bank study on the Mongolian cashmere industry reports:

Mongolian cashmere fiber has been steadily thickening. This drift to coarser fiber diameters has meant that a larger percentage of Mongolian cashmere cannot be used for high-priced garment manufacture. This is the single most important factor impeding the development of the industry. Quality cashmere commands a 30 to 40 percent price premium in international markets, and the coarsening of Mongolian cashmere cost herders about US$16 million in 2001—a 20 percent drop in income for the average household with livestock. Historically Mongolian herds have produced some of the best cashmere, but the quality mix of Mongolian cashmere has fallen over the last decade as herders focused on quantity rather than quality.

Economists call this tragedy of the commons. It refers to when a shared resource is spoiled or depleted because individual actors are behaving in their own self-interest, rather than working for the collective good. You often see it used to describe overfishing, but the term originally comes from a 1833 essay by political economist William Forster Lloyd, who literally used it to explain the effects of unregulated grazing on common land (also known as a “common”) in the British Isles. If the gains of farming are privatized, and the cost of overloading a pasture are spread out, each herdsman has an incentive to add one more animal to his herd – even if it means ultimately ruining the land.

China’s cashmere production is part of an important story of how 400 million people have been lifted out of poverty. Alexander Gerschenkron’s “Economic Backwardness in Historical Perspective” is an excellent text on how poor countries today have to cram two-hundred years of Western industrialization into fifty years just to catch up (think of it like a race where some people had a head start – those behind have to run extra fast).

But if these countries are to protect their long-term interests, both economically and ecologically, there needs to be some effective regulation. That means looking at cashmere’s ecological footprint, species conservation, and responsible consumerism. As Joel Berger writes in “The Globalization of the Cashmere Market,” to do so will require “a critical amalgamation involving planners, local nomads and herders, government officials, fabric industry representatives, anthropologists, economists, and ecologists, as has often been done to facilitate first steps for complicated conservation planning.” Just as the unraveling of the cashmere industry has been structural, conservation efforts have to be on a policy level.

As for consumers, the responsible thing is to avoid cheap cashmere. Cheap cashmere knits stretch out and pill after a season, at which point they just languish in the back of your closet and eventually wind up at Goodwill. And with what one pays for five cashmere sweaters in colors such as “spearmint sprig” and “burnt fennel,” you can get one good sweater in a useful color such as mid-gray, navy, or tan. I particularly like the ones from William Lockie, which are densely knitted from long-fiber yarns. They don’t feel cloud soft at first, but that’s only because they haven’t been over-washed. Good cashmere, I think, should have their softness beaten into them like raw denim.

If paying upwards of $500 for a sweater is out of reach, shop second-hand for a gently used Scottish cashmere knit (look for a made-in-Scotland label, as many heritage brands have since been offshored and stripped of their quality). Alternatively, you can buy a quality Shetland or lambswool sweater nowadays for about $100 to $150. Shetland and lambswool are coarser fibers, so you’ll want to wear them over a dress shirt, but they’re a better value than cheap, disposable cashmere, which today is just a mirage of luxury.